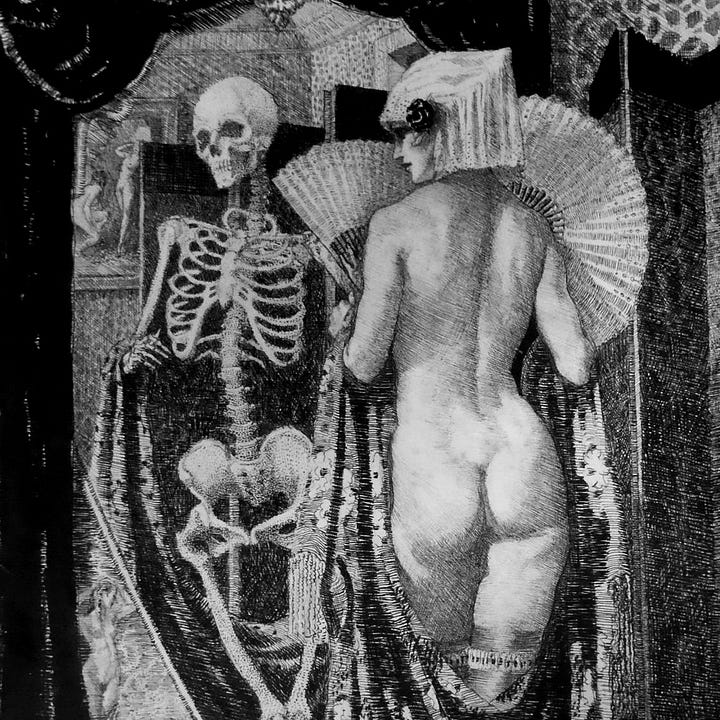

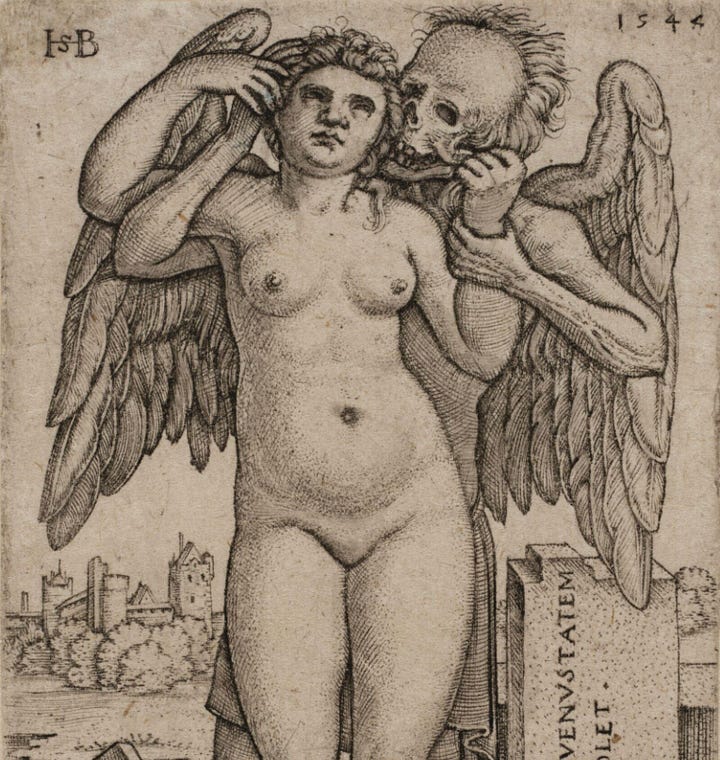

25. Death and the Maiden III

Locking doors is out of the question; anticipation is the conduit of eroticism.

“Late August, given heavy rain and sun / For a full week, the blackberries would ripen. […] / You ate that first one and its flesh was sweet / Like thickened wine: summer’s blood was in it / Leaving stains upon the tongue and lust for / Picking”

by Seamus Heaney, from “Blackberry-Picking” (collected in “Death of a Naturalist”, 1966)

[TW] This newsletter deals with the Intersection of Love and Violence through the “Death and the Maiden” trope, “Beauty and the Beast”, and vampire romance. The word “rape” is used once (in a quote) and not further dwelled on in Section II.IV. Discussions of power dynamics and imbalances are plentiful. Reader discretion is advised, as always.

01/08/2025, London, UK ☆

My dear,

Praise Dionysus! The cold dark approaches once more and my maenad heart beats a little faster. Joyous, wine-drunk ecstasy of the storm. Soon, it will be grey enough to relight the torches within me. The rain is a promising whisper. For now, one must make do with the remains of the sweltering sunlight. This accursed heat. Nothing rotten nor Romantic grows in it with ease. It is a stifling hothouse, but the end is in sight. A good thing, because my patience is fraying at the ends. It is moth-eaten and thinning, delicately delirious.

My dreams have been plentiful. Ever since I stopped sleeping with my head pointed north, they have been vivid and frequent, though refreshingly harmless. It’s good, to have some reprieve. The furniture moves, still, but the terror abates. My nightly wanderings. Reliable puncture wounds in the fabric of time, the thick weavings of it, the syrupy ways of the clock. During daylight hours, writing has been my one, trusty weapon in slowing down the time. Writing as transcendental practice, as meditation, as mysticism for the self-starter. Who needs ecstasy when they have the written word? A baroque use of language is a sixth sense to aid disorientation in the waking world.

Despite the (undesirable) lack of gloom, the past month was full of “vampire girlfriend” themed submissions, bringing a little bit of Forks, Washington or Mystic Falls, Virginia with them. From a story reclaiming the gruesome “Dracula” (1897) narrative, to a haunting photo-editorial, and everything in between. There was a poem channelling the lion and the lamb from “Twilight” (2008). And there were short essays, about cannibalism and vampiric love, and about the patron saint of gloomy graveyard girls. Something for everyone to sink their teeth into, my dear, no matter if you identify as Death or the Maiden. Which brings us to our next order of business.

Another themed submission prompt.

With the return of our beloved Death and the Maiden, our Beauty and our Beast, it’s only right to uphold the tradition of a matching limited-time submission prompt. If you missed out on last year’s submission window, or perhaps have even more to say, rest easy, for you now have a second chance at the afterlife. Take a sip of absinthe and wander down the dark paths of your imagination; imagine a whirl-wind romance with Death, think about the Intersection of Love and Violence(tm), or weep for a tenderness lost out on. Cast yourself as a Beauty, a Maiden, a Psyche, a Persephone, or even their loathsome counterparts. Pick your poison, little dove. Ingest it wisely.

“Lord Death came close to me. I could feel no heat from him, hear no breath in his lung. He was utterly still beside me, but there was a strange comfort in that stillness. It was as if he had eternity to stand beside me, and forever to listen. There was no time or motion to disturb us.”

by Martine Leavitt, from “Keturah and Lord Death” (2006)

Once the feast is over, see what fragile bones can be fished out of the remains. Cast a divination of katabasis, martyrdom, and succulent compassion. What is your own relationship with Death like, personified or not? What does it mean to hold space for the monster? Is there courage in being the lamb rather than the lion? All manner of work is welcome. Old and new, written or otherwise, personal or fictional. Submissions for this themed prompt close on August 30th, and you can find our full submission guide here. Happy submitting!

Without further ado, allow me to open up my jowls. Here, crawl right in. Get comfortable, my dear. This will be a long one.

This newsletter contains the following sections:

I. Archive Sources // II. Death and the Maiden: Tokyo Drift // III. Notes on an Anniversary // “On the List” August // Outro

I. Archive Sources

“Darling, its only the fairy tales we really live by.”

by Katherine Mansfield, from a Letter to J.M.Murry (1920)

You didn’t think I would swallow you up without at least intellectually providing for you first, did you, my dear? No, I fear that is not the way things are done here. It’s best to have some respect for those you intend to devour, after all. Little escapes you, so you must be aware that this here letter is our highly anticipated third instalment of “Death and the Maiden” themed fare. To match, I have sourced a small exhibition of supplementary reading. A minor test of courage. The vows before the marriage.

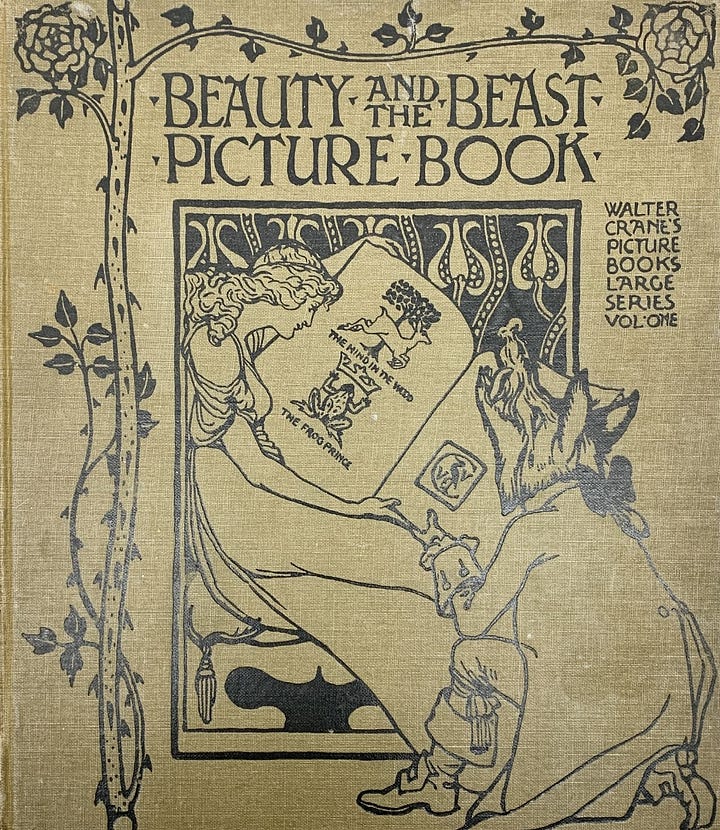

“Beautiful Maidens, Hideous Suitors: Victorian Fairy Tales and the Process of Civilization” - link

This paper uses three Victorian women-authored “Beauty and the Beast” tales to show how the later versions of this story, beyond their original fairytales, recast their focus from the intense and frightening sexuality of the Beast, and instead put it onto Beauty and her navigating of the tale’s gender roles. These Victorian retellings are tales of growth into accomplishment and feminine autonomy construction, contrasting their earlier folk counterparts in their distinctly “civilised” bourgeois conflicts of combined wealth and courtship.

“In the second half of the nineteenth century, British revisions of "Beauty and the Beast" attracted many women writers. Its appeal probably lies in the fact that the story may be viewed as "a female pilgrim's progress," in Marina Warner's terms: it deals with the violence of male sexuality, which the heroine must learn to tame-and accept—and which marks the main stage of her education into womanhood.”

“The Supple Suitor: Death, Women, Feminism, and (Assisted or Unassisted) Suicide” - link

Using a host of poetic examples, this paper looks at how the “Death and the Maiden” tradition and its framing of Death as a flirtatious suitor in the artistic imagination have created a gendered idea of the “erotic suicide”. While the death drive (thanatos) is, in itself, not gendered, the ways in which men and women typically yearn for death is. It could be said that men typically write about their longing for death in a more conceptual sense, purely as respite, while women tend to personify and eroticise Death, as figure, falling in line with how the arts have portrayed the union of Death and the Maiden. Think of my favourite transcript from “Romeo and Juliet” (1597); “Why art thou yet so fair? Shall I believe / That unsubstantial Death is amorous, / And that the lean abhorred monster keeps / Thee here in dark to be his paramour?” (Act V, Scene III)

“Did Dickinson not only dread death and dread her dread of death but also, at the same time, fear wanting death? Certainly the constellation of anxieties around the erotic encounter of Death and the Maiden suggests that she was using this centuries-old theme to explore a troublesome aspect of her preoccupation with her own demise. Both "Death Is the Supple Suitor" and "Because I Could Not Stop for Death" elaborate the tale of the phantom wooer and the fainting female, exposing not only the potential deadliness of the erotic, but also, more to the point in the context of my theme here, the seductive eroticism of death.”

“Beauty and the Beast, or, the Wound Too Great” - link

As a “Beauty and the Beast” retelling, Clarice Lispector’s version is unique in the sense that it features no romance. Instead, Lispector has utilised her Beauty, and put the Beast indefinitely off-screen, to narrow in on the class aspect of the fairytale. Beauty, relegated to the identity of a housewife and full-time enjoyer of lavishment, gains something almost akin to class consciousness through her run-in with a homeless man. A most interesting continuation of the wealth dynamics in the original French fairytale.

“She saw that she didn't know how to run the world. She was an in-competent, with her black hair and long, red fingernails. That's how she was, like in an out of focus color photo. Everyday she made her lists of things that needed doing or that she wanted to do the next day…..that was how she'd become so tied to idle time. She simply had nothing to do. Other people did everything for her.”

II. Death and the Maiden: Tokyo Drift

“Give me your hand, you fair and tender creature; / I am a friend and do not come to punish. / Be of good cheer! I am not savage, / Gently you will sleep in my arms."

by Franz Schubert, via Archive Source 2

By now it should be clear to you, my dear, that my thoughts about “Death and the Maiden” are a plentiful, overflowing, never-ending well. I wrote a full-length 12k word thesis about the subject last year for the White Lily Society’s first Substack anniversary, and now I am back to regale you with yet more. Brevity not desired, obviously. This is indulgence of the finest kind, extravagance and excess in service of celebration. It goes without saying that this letter builds on what has come before it, so do run your eyes over the modest part I, and its much more elaborate sequel, part II, before braving this here part III. Jumping into the latest part of the trilogy is not entirely recommended. You have been warned aplenty.

In a previous letter, we looked at the “Sleeping Beauty” fairytale in depth, starting with the original tale, and then semiotically dissecting it in turn. This letter will borrow a bit of the former’s structure, using the “Death and the Maiden” parallel “Beauty and the Beast” to provide us with our beginning structure. For easier reading, I have indexed the sections of this thesis of mine below. It’s highly recommended to use the search command to skip to certain juicy bits if you so desire. Or you could simply sit back with a warming cup of tea, my dear, and let me take you by the hand. The choice is, as always, entirely yours.

Index.

II.I “Beauty and the Beast” - recounting the original BatB fairytale and its hallmarks

II.II “Animal Brides and Bridegrooms” - about gendered conventions in fairytale BatB stories

II.III “the Erotics of Captivity” - dreams of annihilation, or, “why Death is sexy”

II.IV “Death as Maiden” - links between femininity and death (contd.), feminine jouissance, and maenads

II.V “the Call of the Monster” - Death and the modern romance hero as amalgamation of seductive villain and virtuous hero

II.VI “Dream-walking / Death-walking” - dreams, sleepwalking, and “Nosferatu”

Enough stalling, let us open the storybook now.

II.I Beauty and the Beast

“Beauty, take these flowers. They have cost your poor father dearly.”

by Maria Tatar, from “Beauty and the Beast” (as found in “Beauty and the Beast: Classic Tales About Animal Brides and Grooms from Around the World”, 2017), p32

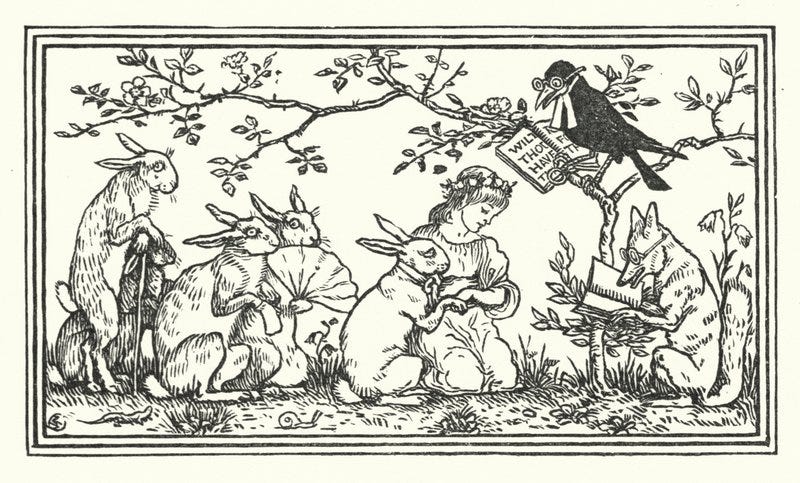

Our beloved “Beauty and the Beast” is categorised by Hans-Jörg Uther’s 2004 “the Types of International Folktales: a Classification and Biography” as a tale type 425C, aptly also named “Beauty and the Beast”. But the story is also often combined with tale types 300 “the Dragon Slayer”, 425 “the Search for the Lost Husband”, and 425A “the Animal as Bridegroom”. Before the French bourgeois spin of nightly suppers, maiden sacrifice, and an unlikely love story, earlier folktales composited elements of beastly adversaries, of animal brides and bridegrooms both, and their spouse’s quests to return them home after a fatal error. Either way, the traditional “Beauty and the Beast” (from hereon out abbreviated to BatB) we were raised with, tale 425C, often has the following key ingredients, as specified by the very in-depth “Thompson Motif Index of Folk Literature”1:

L221 Modest request: present from the journey

S222 Man promises (sells) child in order to save himself from danger or death

C761.2 Taboo: staying too long at home

D735.1 Beauty and the beast. Disenchantment of animal by being kissed by

woman

The traditional BatB story starts all the way back in 1740, with a tale penned by the French Gabrielle Suzanne Barbot de Villeneuve, and was later, in 1756, taken under de wings of Jeanne Marie Leprince de Beaumont for some small tweaks. Villeneuve’s version emerges already formed, quite close to the story we know; after the loss of his goods and, consequently, his fortune, a merchant is forced to live in poverty with his three daughters, and three sons. But in the midst of their ceaseless complaining, the youngest daughter stands out. Not just for her positive outlook, but for her gorgeous looks: she is called Beauty, of course. One day, the merchant ventures into town on word that his wares have safely arrived after all.

Before he goes, he asks his children what he should bring back with him as gifts, now that their riches are due to be restored. Everybody asks for lavish, expensive presents, but Beauty wants only for a single rose. The news soon turns out to be a falsehood, and defeated, the merchant starts the arduous journey home. Worsening weather and misfortune lead him to a mysterious mansion, where he finds the table set, the fire lit, and a comfortable guest room prepared for him. Now, who could refuse such hospitality when in need? Who would even want to?

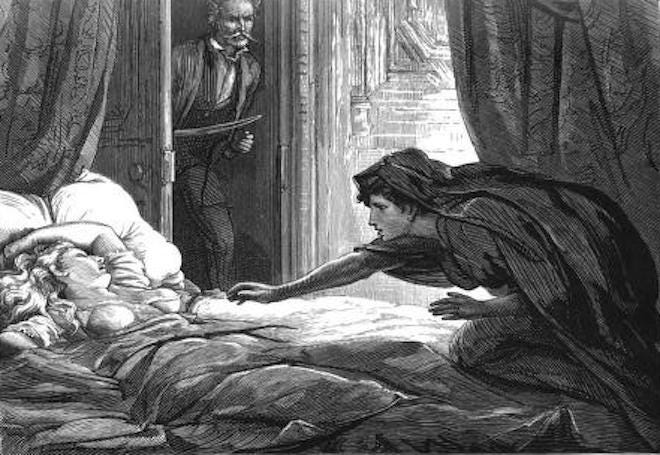

Above: the merchant finds the Beast’s mansion. From “The Beauty and The Beast” (originally “Skønheden og Dyret”, 1989). Original Image Source: see film

Without any trace of his host, the merchant gets ready to leave when his eye falls on a magnificent rose bush in the gardens. It is a thing of beauty, thorns and all, a gorgeous blood-red sea of blooms. And while he is downtrodden in his persistent lack of wealth, he finds himself eager to grant at least one of his children’s wishes. So, he plucks one flower from the bush. Almost instantaneously, he is faced with the lord of the home; a dreadful Beast, who instills a great terror in the merchant. The Beast cuts him a deal; die for his offence, or send one of his daughters in his place. Of course, the merchant swiftly agrees, not at all intent on holding up his end of the bargain, and returns to his children.

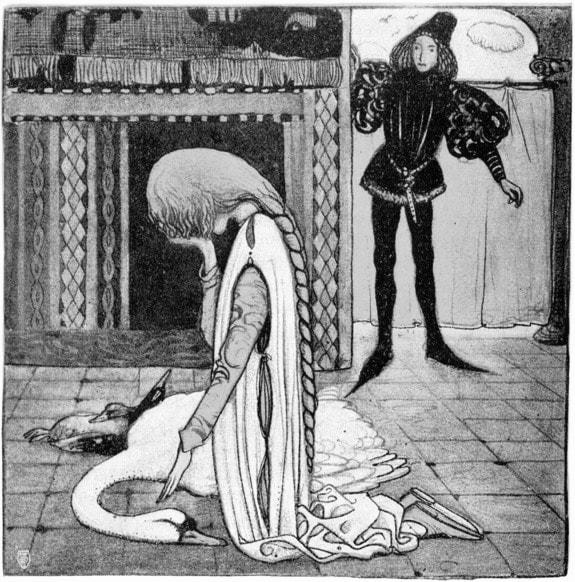

Back home, he recalls the story to his daughters, gloomy and terrible. The rose has begun to wilt already. Beauty does not need to be persuaded to take her father’s place, as her great empathy leaves her no other choice. And so, she makes her way through the woods and to the house that is to be her presumed executioner’s block. She seems unable to do anything but bare her neck. But the Beast immediately defies expectations by confirming that Beauty has come of her own free will. To her surprise, he does not plan for her imminent death, does not plan to devour her, bones and all. Her room is of the greatest comfort, littered with books, and she is a mistress of the home just as much as she is a prisoner. She finds in the Beast a humble, giving companion.

“‘Beauty’ said the monster, ‘will you let me watch you dine?’. 'You are my master,' said Beauty, trembling. 'No, you are the only mistress here,' replied Beast. 'If I bother you, order me to go, and I will leave at once [...].'"

by Maria Tatar, from “Beauty and the Beast” (as found in “Beauty and the Beast: Classic Tales About Animal Brides and Grooms from Around the World”, 2017), p35

In Villeneuve’s version, the Beast asks Beauty every night to sleep with her, in de Beaumont’s, he asks for her hand in marriage. No matter the offer, Beauty politely declines, carefully to avoid hurting the Beast’s feelings. There are many more, small differences. Villeneuve implies false parentage for Beauty, making her royalty— something which her tale shall return to in its final act. De Beaumont doesn’t bother. Villeneuve populates the manor with animal servants, while Beaumont keeps the pair in seclusion. In both, Beauty dreams of a fairy warning her of making judgment calls based on appearance, but in Villeneuve’s, she also dreams nightly of a mysterious, handsome stranger…

Even as the months pass them by, and Beauty begins to warm up to the Beast’s gentle, thoughtful ways, she cannot help but be consumed by a most intense homesickness. She builds up the courage to ask the Beast for leave, and he agrees, on condition that she returns within a certain amount of time, or he’ll die of a broken heart. Using a magic ring, Beauty is immediately home with her father and siblings, and it does her well. In Villeneuve’s version, it is Beauty’s brothers that can’t bear to part with her. In de Beaumont’s, it’s Beauty’s sisters, seeing her fine dress and jewels, who feel a renewed jealousy— they plot and scheme to make Beauty overstay, hoping she will incur the wrath of the Beast. Regardless, Beauty gives in and stays longer than intended.

Waking up in a cold sweat, she then has a dream of the Beast, lying dying in the courtyard, grief-stricken and abandoned. She returns posthaste to find her vision true. Realising her true affections for him, combined with the looming loss of the beloved, she fetches him some water to revive him. Words of love are exchanged, and after a night of enchanted sleep (Villeneuve) the Beast transforms back into the beautiful stranger of Beauty’s dreams. Or in de Beaumont’s case, the Beast spares no time waiting and reveals his true form on the spot. Villeneuve’s fairy-shaped Chekhov’s gun returns to tell Beauty of her royal lineage, and de Beaumont brings in a never-seen-before fairy to turn Beauty’s sisters into stone for their conniving wickedness. Beauty and the Beast (now, a prince) are married, to live happily ever after, my dear.

Sensible writers would let the story end there, but Villeneuve tacks on several lengthy sections detailing the backstory of the Beast. Economic eliminations on de Beaumont’s part, who removed these frills entirely. Fairytale savant Charles Perrault also adapted the tale, mixing elements of both versions. Perhaps the most famous BatB adaptation, the animated 1991 Disney version, chooses to re-use parts of Villeneuve’s backstory, opening the tale with the story of a young prince, home alone and refusing to shelter an old beggar woman.

Not an odd concept to modern audiences, perhaps, but as the woman reveals herself to be a fairy, the prince gets cursed, to be stuck as Beast until he can find someone who loves him as he is before the petals of an enchanted rose all fall off. A nice continuation of the rose motif, if you ask me, though entirely uncalled for to have the Beast’s household of servants all turn into whimsical, anthropomorphised household objects. Spare the innocent, at least! But I understand this is Disney after all, and we need a cast to dance and sing our songs— which will certainly not be the frightful Beast.

The Disney version undoubtedly leans hard on the appearances thing, as Villeneuve and de Beaumont’s fairy would approve of. “Don’t judge a book by its cover” and all that. Sometimes the beasts are really human, and the humans are beastly. Yet BatB is a pairing that, symbolically, can be utilised for a very wide variety of morals and deeper cultural meanings. It could be said to represent female anxieties about arranged marriages, the dangerous allure of human sexuality, or moralise about the transformative power of love. Not to mention the perverse shock value of the arrangement: innocent girl, held captive by a grotesque beast. Its roots lie in myths like that of Zeus and Europa, or Eros and Psyche.

The juxtaposition is of the sweet and the terrible, but also the poor and the wealthy, the empathetic and the animalistic. Conflict between body and soul. The animal and human pairing asks us to think outside these lines, for the Beast is certainly an animal, but he is also above other animals as he can talk, and think, and own property. The Beast defies convention in that way. He is a representation of the more animalistic urges, Freud’s “id”, yes, but he has in him also an unexpected dash of civilisation. And yet despite the Beast’s potency as sexual symbol, his union with Beauty is affirmatively one of companionship over passion, of making the most of it, of tending to love in the hopes that more can bloom.

Unlike the myths it takes from, BatB presents a much more nuanced, withdrawn version of love focusing largely on consent2 and patience. The Beast doesn’t [physically] force himself on Beauty. Beyond the original captivity, he allows her to set the pace within the confines of their forced proximity. But do not be mistaken by the sweet façade. The taming of the Beast is only enforced by the narrative it inhabits, the cage the words make for him, and the erasing glance of the author. There are still plenty of signifiers of eroticism and passion within the narrative, as we shall come to see in later sections.

II.II Animal Brides and Bridegrooms

“If Little Red Riding Hood frames the relationship between humans and beasts in terms of predators and prey, then Beauty and the Beast stories contrastingly tell us that, in a heartbeat, humans can become beasts and vice versa.”

by Maria Tatar, from “Beauty and the Beast: Classic Tales About Animal Brides and Grooms from Around the World” (2017), p.xxi

Gender is, without a doubt, an essential part of the BatB trope, as well as that of DatM. But it also creates one of its most fascinating paradoxes: theoretically, both Death and the Maiden are gendered stereotypes taken to extremes. Brute force and sweet sensibility personified. And yet they both exist as liminal characters, time and time again, driving themselves, inevitably, towards polarity. They are characters of contradictions, even if the gendered undertones still largely dictate their behaviour.

Gendered attitudes to the DatM coupling are much clearer in BatB stories and its subsidiaries, early folk- and fairytales of animal brides and bridegrooms. In a strictly heteronormative BatB narrative, reversing the roles only reinforces this idea of difference. The animal bridegroom is a fixer upper, the animal bride is in need of capturing, not fixing. Per Maria Tatar; “In traditional animal bridegroom tales the man is portrayed as a predatory animal because he needs to be domesticated; the woman, for her part, is highly civilized.” (see Archive Source 1). Animal bride tales are largely about denying one’s deeper nature, about choosing contentment in captivity.

This is an odd contrast to the monstrous feminine as it is often depicted in horror, as a cunning threat to male power. The animal bride instead is a perfect woman, whose quest lies not in transforming herself, but in proving her own worth to others. She is met with human suitors who think little of her capacities as a domestic force, of her magic, or even of the beauty hidden underneath her animal skin. Because all animal brides are, without their unshapely cloaks, beautiful maidens. And they are always the most beautiful maiden around. No second best here, my dear. The rose that blooms for you is, without a doubt, the most precious one of all. Everybody is always saying so. Judged by jury and executioner, we find that she exceeds all others.

Reading a great amount of tales of both animal brides and bridegrooms, it is quite striking how different their stakes and story motifs often are. Animal bridegroom stories tend to have their female protagonists’ greatest sin be curiosity, or meanness, and they go on long, arduous quests to reverse their ill fortune. Once they break their animal partner’s trust, they must go to Herculean lengths to repair it. But they can never reverse the flaw of being born as women. These are the Psyches, who need to see the Beast that lays with them, who get their hands on Bluebeard’s keys, and can’t blindly follow orders— their instincts just won’t allow them to live uninsured. Complete trust is not so easily given by them. And this lack of blind obedience is a threat to the assumed power of the male. Even when the man of the house is a monster, is a beast, he is still better than a woman by authority of his gender, so the blame is always on her.

Even in stories of animal brides, the defining sin that drives the story’s main plot is feminine in character. Though their stories often silently open with assumed male ownership and domination, the onus of guilt is on the woman for fleeing, not on the man for “capturing” (read: “taking”, “abducting”, “forcing”) what is not rightfully his. It is entirely expected for these male protagonists to harbour magpie instincts. The tale of the animal bride is one that disputes and debates ownership over her.

Sure, the human male protagonists are much more likely to end up dead for their crimes, but that is a symptom of the increased violence in animal bride tales as opposed to their animal bridegroom counterparts. In a Japanese tale, a crane spins a beautiful cloth straight from her own chest, dabbled with her heart’s blood. A man “takes advantage” of a bull, or a bear-bride foresees her own death, as in two Native American tales. The female marriage candidates found to be second best to the animal-bride-turned-human are drowned in a river. A man gets upset with his donkey wife, and publicly throws her against a wall, after which he is rewarded with her final transformation into a beautiful maiden. Leagues of these story feature hunter protagonists, both literally and symbolically, ensnaring their brides in the wild and forcing them to stay. Of course, in the fantastical world of the fairytale, happiness is likely even in an unlikely marriage.

“From his hiding place the young hunter had taken a careful note of where his enchantress had laid her swan feathers. Stealing softly forth, he took them and returned to his place of concealment in the surrounding foliage. Soon thereafter two of the swans were heard to fly away, but the third, in search of her clothes, discovered the young man, before whom, believing him responsible for their disappearance, she fell upon her knees and prayed that her swan attire might be returned to her. The hunter was, however, unwilling to yield the beautiful price, and, casting a cloak around her shoulders, carried her home.”

by Maria Tatar, from “the Swan Maiden” (as found in “Beauty and the Beast: Classic Tales About Animal Brides and Grooms from Around the World”, 2017)

What is the beast to the fairytale? Is the fairytale sympathetic to the Other? What message is aided by the asymmetry of species and gender? Unlike the female vampire, whose monstrous feminine sin lies in being a seducer, the animal bride is not hunter, but prey. The story barges down her doorstep and takes her with it, kicking and screaming. The wild bird, captured and moulded into the shape of a girl, her skin thrown into the fire, forcibly severed from her animal nature, is eventually nothing more than a prisoner of matrimony. Feral, yet biding her time. Once you show her the keys of the cage she will not hesitate to leave the nest. And unlike the female protagonists of animal bridegroom tales, the male protagonists won’t chase after their animal brides. There are always more fish in the sea to marry and court.

“[…] seven years later, the hunter related to her how he had sought and won her. He brought forth and showed her, also, the white swan feathers of her former days. No sooner were they placed in her hands than she was transformed once more into a swan, and instantly took flight through the open window. In breathless astonishment the man stared wildly after his rapidly vanishing wife […]”

by Maria Tatar, from “the Swan Maiden” (as found in “Beauty and the Beast: Classic Tales About Animal Brides and Grooms from Around the World”, 2017)

II.II the Erotics of Captivity

“I have seen the cage you are weaving for me; it is a very pretty one […] for I loved him with all my heart and yet I had no wish to join the whistling congregation he kept in his cages although he looked after them very affectionately, gave them fresh water every day and fed them well. His embracements were his enticements and yet, oh yet! they were the branches of which the trap itself was woven.”

by Angela Carter, from “the Erl-King” (collected in “the Bloody Chamber”, 1979)

The story of BatB also brings to the foreground cultural differences in how love and sex are thought of, and often separated. Think of the genre of “courtly love”, for example, which Lacan refers to as “a highly refined way of making up for (suppléer à) the absence of the sexual relationship.” (from “On Feminine Sexuality, the Limits of Love and Knowledge”, 1975, p69). The assumed absence of sexuality beyond subtext in the fairytale is a part of the culture and history it was born into. Polite literature during the birth of the BatB tale prefers to dance around the sexual act entirely, and to focus itself more largely on the ideas of romance. Likewise, taming the erotic spirit was the purpose of courtly love, in order to bend romance to ideas of chivalry, sacrifice, and a transcendence devoid of bodily benefit. It is a love entirely devised for the soul, not the skin. A love that exists in the heart, and so cannot be touched. And like the separation between love and sex, sex itself is also divided into its comfortable and uncomfortable parts:

“Human sexuality has at its core a basic conflict between tenderness, affection, and compassion on the one hand, and violence, aggression, and rough-and-tumble play on the other. That the language of love so often draws its power from the language of combat and the hunt reveals exactly how divided we are when it comes to considering the operation of sexual desire.”

by Maria Tatar, from “Beauty and the Beast: Classic Tales About Animal Brides and Grooms from Around the World” (2017), p.xxv

Perhaps this split in narrative is personified in BatB: Beauty as Love, Beast as Sexuality. But the lines aren’t entirely so crisp.

Complicating matters even more, the boundaries of consent, domination, and submission are often blurred within BatB. While the Beast requires that Beauty comes to him of her own free will, what choice is there in the alternative, sending one’s father to the executioner? Combine that with continuous offers of courtship, and the waters are murky. The DatM trope, like BatB, loves to work the narrative within set physical confinements, enabling the erotics of captivity. The pairing is already eroticised in nature, ready-packaged with soft gasps and a potential for warring cruelty and tenderness, but the captivity element only underlines this. Vulnerability is the life-blood of this eroticism. Wound-showing-turned-romance.

It is important to note that captivity, here, comes without the association of bondage, without the association of servitude. Actually, in many BatB adaptations, the Beast lifts Beauty out of her sisters’ servitude— Beauty is a concentration of stereotypically “feminine” traits, but not forced to act on the domestic side of these. When she is caring, or nurturing, or gentle, she is so out of her own volition. The Beast does not make her cook, nor clean, but instead lavishes domestic devotion onto her. Fresh cut flowers, dresses and jewels, and extravagant nightly meals are all par for the courtship. The magical mansion in Beaumont’s version enables this even further, having no visible servants (no exploitation), but still presenting a veritable buffet of excess.

The castle as a property is frightening in the sense that its impregnable walls make clear that the vulnerable part is inside. The chambers of the heart. Within the castle’s stone walls and twisting hallways is a predator waiting for you. The killer is already inside with you. No need to invite him in. Locking doors is out of the question; anticipation is the conduit of eroticism. And that is eroticism in the philosophy of Bataille; the complete disconnection from individual identity facilitated by ecstasy. Coming, of course, from the Greek ekstasis; to be beside oneself. In that sense the castle is reshaped into labyrinth, with the Beast as its minotaur, architecturally representing the labyrinthine ways of the maze of courtship. What is gentle and polite, when one’s circumstances are so barbarous?

Loving the Beast (Death), ultimately is an act of masochism, in which Beauty (the Maiden) blurs her identity in pairing with the Other, who at once signifies desire and male agency. Simone de Beauvoir called it a “dream of annihilation”: “when woman gives herself up completely to her idol, she hopes that he will give her at once possession of herself and of the universe he represents”. (from “the Second Sex”, 1949) In DatM, it can be said that the Maiden partially yearns to die, in order to become Death. To take the aspects of him she has traditionally been disallowed. This is also true for the Beast, who sparks a curiosity in Beauty and in the reader, even more so as the Anthropocene advances. The curiosity only the repressed parts of us can evoke. “In a society in which most of us will never encounter true danger in the woods, the bear who comes knocking at our window is not such a frightening creature; instead, he’s exotic, almost appealing.” (by Maria Tatar, from “Beauty and the Beast: […]”, 2017). The more we disconnect from the natural world, the greater its appeal as cabinet of curiosities becomes.

Having one’s autonomy taken away is easily eroticised as submission; when Fleabag, from the modern show (2016-2019) of the same name, laments that she wants someone to think for her, to take the wheel on her life, it is an erotically charged confession. Masochism in the form of dissociation. This masochistic perversion was long thought to be natural in women, to be an extension of the “natural” feminine submission to male power. Wives were expected to submit to their husband’s will, the same way daughters submitted to their fathers. The picture of the self-flagellating devotee was a woman. Martyrdom, in turn, is a profession lined with women. Remember, my dear, it is the woman who chases after her animal bridegroom. When the roles are reversed the plot does not demand the male hero to go to such extreme lengths.

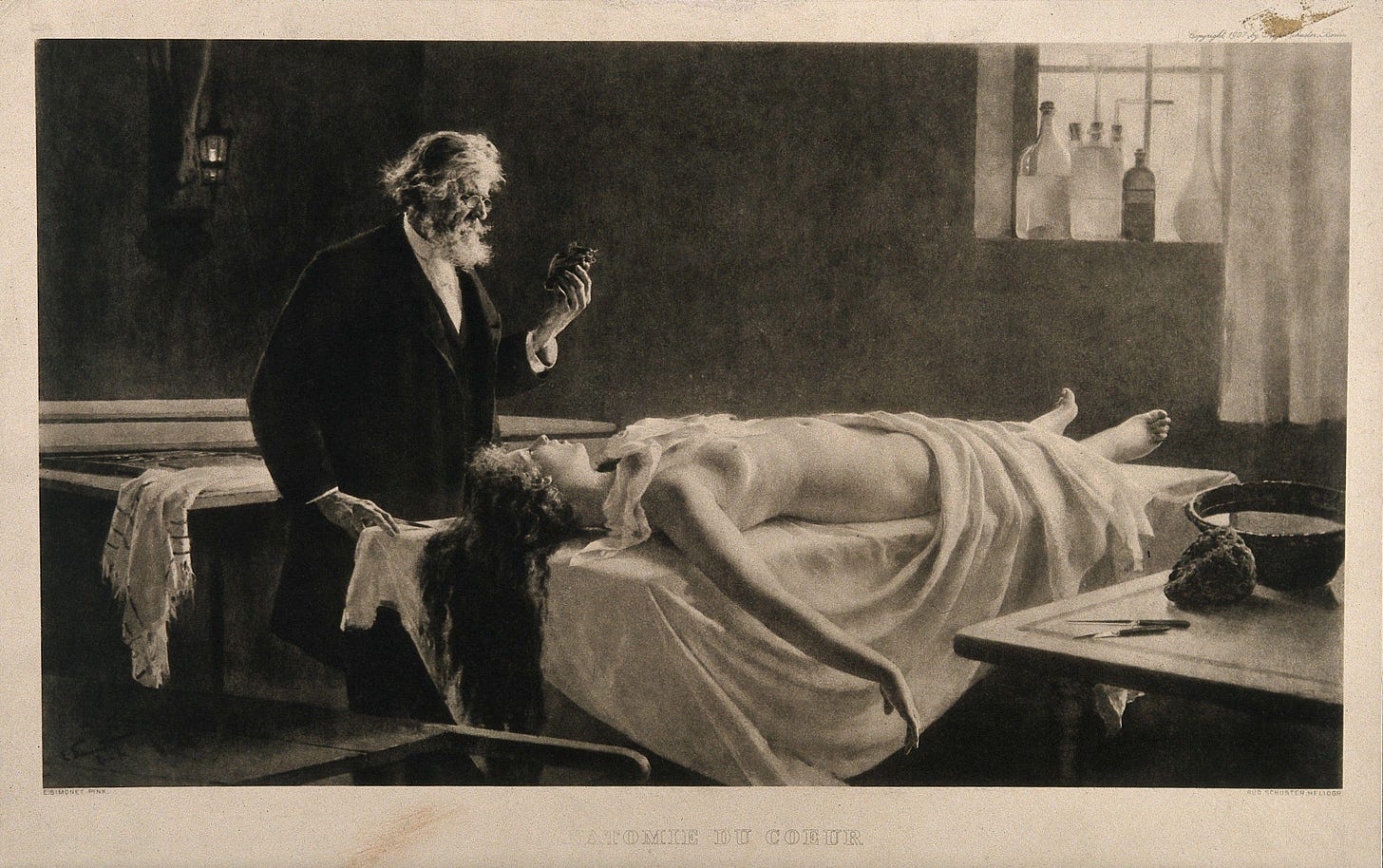

II.III Death as Maiden

“[…] the perennial sadness of a girl who is both death and the maiden.”

by Angela Carter, from “the Lady of the House of Love” (collected in “the Bloody Chamber”, 1979)

Much has been written about the innate connections between femininity and death3. Edgar Allan Poe famously wrote that “the death of a beautiful woman is, unquestionably, the most poetical topic in the world” (from “the Philosophy of Composition”, 1846). To be a woman, a girl, is to be a veiled being, living in the margins of a world not made for you. Mildly alike to being queer, or belonging to any other kind of minority. Which is why the DatM structure lends itself so well to queer or mixed-race interpretations, adding more depth. The figurative “Maiden” is Other, more like Death than “she” might know. Everything else is entirely open to interpretation.

Certainly, DatM lends itself to re-interpretation much more than the hetero-normative, largely wealth-obsessed gaze of BatB. When Louis and Lestat embrace, for example, in the AMC adaptation of “Interview with the Vampire” (2022-), their union is one of close understanding, because they are both outsiders to some extent. Louis, as a gay person of colour in 1910s New Orleans, and Lestat, as self-appointed “non-discriminating” creature of the night, as ultimate predator. They are closer for their individual “outsider” status, but still invariably far apart within society. DatM breeds a certain kind of thematic understanding that is also, inevitably, full of tension. Their common ground does not seamlessly make way for romance, but it might enable it.

In historical romances we might label as DatM, the outsider or Other was also understood to represent a different kind of death; a social one. Cathy of “Wuthering Heights” (1847) can’t be with Heathcliff, because his race and class would essentially force her into the ultimate ego-death, to give up the life she has been accustomed to, the prejudices she has seamlessly accepted that allow her to live the way she does. Their romance would require her removal of the veil of ignorance, and she finds that too much to ask of herself. An un-comfort too large. Jane, in “Jane Eyre” (1847) could not give up the social security of marriage to be with Rochester, regardless of their passion. The iron grip of comfort is the ever-alluring, antithesis to unification with Death.

The [contested] marriage, as stand-in for a more symbolic unification, extends the otherworldliness of this cliff between the respective worlds of Death and the Maiden, of society and outsider, of living and dead. Elisabeth Bronfen, author of “Over Her Dead Body: Death, Femininity and the Aesthetic” (1992), writes about the ambiguity of the “bride” figure, that is, the woman between adulthood and marriage, as “undefinable” because “the danger and fascination that the bride exerts can also be attributed to the fact that she could potentially belong to everybody, that she could be anything and everything” (p270). The woman, in her hyper-flux of identity states, as object both with and without direct ownership, threatens and fascinates the male order. She is both dead and alive, undead, in the process of dying and of living, of being reborn. In that sense she is Death: like him, she oscillates between existing as invisible spectator and spectacle of threat.

Does the Maiden wish for invisibility, like her beloved Death? Does this slipping in and out of roles like plush robes ultimately suit her? Can the margins be made into a home? Arguably, to be a woman is to be looked at, to be treated as aesthetic object of erotic voyeurism in life, and in death. To be a beautiful woman is even more so. The animal bride is both victimised and protected because of her beauty; the swan who takes off her animal skin to bathe gets marital shackles for her sin of existing as both beautiful and unclaimed, while the cursed frog helping a prince eventually has to prove herself as both adept and beautiful in order to survive. But more often than not, to be beautiful is enough to be considered as bride, as object to be claimed, as reward for a male hero’s bravado.

“"Beauty can be a great threat." Her extreme grace became confused with bewilderment and a deep melancholy. "Beauty frightens." "If I weren't so pretty, I would have had some other destiny," she thought […]”

by Clarice Lispector, see Archive Source 3

Hypothetically, the freeing embrace of Death should be the end of beauty. But the beautiful corpses littering art continue an aesthetic claim over the beautiful as property; “culture uses art to dream the death of beautiful women” (by Elisabeth Bronfen, “Over Her Dead Body”, 1992, p.xi). The embrace of Death is one that lifts social stigma and restrictions, because it is at least partially built on understanding. “Of course she comes alive in this house of death.” (by Sarah Krasnostein, from “The Trauma Cleaner: One Woman's Extraordinary Life in the Business of Death, Decay, and Disaster”, 2017). But neither death nor beastliness can save the Maiden from the innate performance of beauty. The corpses are lovely and the animals were actually gorgeous maidens all along— which is why Angela Carter’s decision to end one of her BatB adaptations (“The Tiger’s Bride”, 1979) with Beauty joining the Beast in his inhuman appearance is so subversive.

The DatM and/or BatB romance is essentially a dispute of ownership. The Maiden as beautiful bargaining chip. “As we have seen / in the tale of Persephone / which should be read / as an argument between the mother and the lover— / the daughter is just meat.” (by Louise Glück, from “Persephone the Wanderer”, collected in “Averno”, 2006). When the argument isn’t between mother and lover, it is between [male] society and those that exist beyond it: “[…] in the horror film, the wanton sexuality of monsters is not primarily feared because of the damage it may do to the hapless woman involved, but because it is an affront to male sexuality” (by David J. Hogan, from “Dark Romance: Sex and Death in the Horror Film”, 1986, p93).

The idea of the woman unclaimed threatens the male order. Following Jacques Lacan’s philosophy, the woman “does not exist” because she is defined as not-man. There is no defining the woman, as she escapes an encompassing neat definition. Language and symbolism cannot expand widely enough to envelope her completely. This is in line with our idea of the Maiden, who is simultaneously alive, dead and dying, always. Through her existence outside of the male (phallic) order, she threatens it, because it opens her up to a unique kind of pleasure; what Lacan calls “feminine jouissance”. It’s Bataille’s “eroticism” enabled by an existence as Other, as undefined, as non-existence. Essentially, feminine jouissance is rapture, possession, bliss.

While phallic jouissance is limited by structures like language, or law, feminine jouissance, as extension of the woman’s “Otherness”, is a smile of ungoverned, ungovernable excess, even mysticism. It is beyond understanding and impenetrable, thus it is frightening. Lacan long understood this when he wrote that women are more suited to mysticism, to transcendence through the loss of the self. The undefinable concepts are the woman’s home.

Perhaps this is what the maenads, Dionysus’ female followers, felt as they feasted to excess in their bacchanals, their rituals of wild and drunken abandon. Did they feel the presence of their god as they ripped men apart with their bare hands? Did they feel freed from their non-existence? Was the loss of identity, ultimately, an erotic occurrence? Bataille would certainly concur. Dionysus is also the god of insanity, after all. And insanity is a space of both a beautiful terror and a unique ecstasy. “Beauty is terror” wrote Donna Tartt; “Whatever we call beautiful, we quiver before it” (from “the Secret History”, 1992). The sacred can bring us to our knees: “The fear and trembling that modern man cannot rid himself of when faced with things sacred to him are always bound up with the horror inspired by a forbidden object” (by Georges Bataille, from “Eroticism”, 1957, p223). I shouldn’t have to tell you that fear is an aphrodisiac, my dear. The abject- Kristeva’s space where terror makes meaning collapse- can also be richly seductive. “Abjection is a resurrection that has gone through death (of the ego). It is an alchemy that transforms death drive into a start of life, of new significance.” (from “Powers of Horror: an Essay on Abjection”, 1941, p15).

“We love the wolf. We love the love of the wolf. We love the fear of the wolf. We’re afraid of the wolf: there is love in our fear. Fear is in love with the wolf. Fear loves. Or rather: we are afraid of the person we love. Love terrorizes us”.

by Hélène Cixous, from “Love of the Wolf” (collected in “Stigmata: Escaping Texts”, 1998)

Being close to terror via Death can very much be a form of healing for the Maiden; 2024 film “Lisa Frankenstein” posits this as its mission statement, having its main character Lisa Swallows accidentally resurrect a corpse, and then embark on the ultimate romantic quest— the quest to put him back together. With a few axe murders along the way, of course. This monstrous, undead man, explicitly not a part of the phallic order as he lacks a working phallus, is both Death and the Beast. He exists to be stitched back together, literally. He is transformed. Yet in a way, the narrative gives him the feminine archetypal arc; there to support, prop up, and propagate Lisa (the Maiden’s) journey through identity formation, grief, acceptance, and ultimately, death. His physical mini make-over is there to enable her spiritual, then-physical transformation. Who knew dying for love could be so sweet?

But Lisa is also somewhat of a monstrous feminine character, in the sense that she isn’t shy to bare her teeth. We have previously looked at the Maiden in more detail, undoing her stitches, but it serves to be reinstated here. The male order would rather have the woman as perennial victim; as delicate, fragile object in need of protection. The beautiful corpse. The monstrous feminine subverts this by making the woman the predator, instead of the prey. Pretty skirts pair better with sharp teeth.

Sometimes, the figurehead is all the Maiden is meant to be. She can certainly read that way. Saccharine and sickly sweet. Most times, though, she exceeds her own stereotypical confinement through the nuance provided to her by what should, by its own reasoning, be a tale of strict divergences. Death and the Maiden close the gap of understanding in service of supporting each other’s narrative growth, and ultimately, transformation.

II.IV the Call of the Monster

“There’s something about a guy who’s mysterious, and dark, and you don’t know everything about that’s very appealing, because the girls always like the bad boy”

from an interview with Nina Dobrev, who played Elena Gilbert on “the Vampire Diaries” (2009-2017)

So, the Maiden is a threat because of her Otherness, because she actively desires the Other, Death. This active desire is an antidote to the stereotypes of the female condition: “To be the object of desire is to be defined in the passive case. To exist in the passive case is to die in the passive case- that is, to be killed.” (by Angela Carter, from “the Sadeian Woman and the Ideology of Pornography”, 1979, p88). But what is there to desire about the Beast, about Death? Specifically, what makes the Maiden desire him? We have already seen that men and women’s ideas of Death personified take on different meanings in Archive Source 2.“[…] women poets have often imagined death as multiply and richly seductive.”

It is not simply the call of the void, or death drive (thanatos), that drives the Maiden into Death’s arms. Remember, in Greek mythology, Eros and Thanatos were “nearly” twinned personifications. Romance and Death encircle each other, as do Desire and Terror, Love and Violence. Death and the Maiden are the ultimate Intersection of Love and Violence. Which is why it’s interesting to also further dissect the figure of Death / the Beast, and all his contradictions. Because neither Death nor the Maiden wholly rule the domain of Love, or Violence. They both partake in either cup.

Being the absolute representation of everything stereotypically thought to be “male”- social and economic power, brute strength, sexuality- Death (the Beast), like the Harlequin romance hero, represents a threat to the Maiden’s (Beauty’s) chastity, innocence, and world view. This somewhat questionable sexual threat is not actually about being “ravished”, so to say, but instead offers an opportunity to play coy about the very real bodily and emotional threats of courtship. A wink and a nod at the fictionalised surroundings in which there is never any real danger, and where it is often the female fantasy that casts itself in the role of prey. “It is not a question of a pornography of a rape-fantasy or an erotics of violence; rather, it is a simple, an elementary way of realizing in character and action the violent danger that sexuality in the abstract is understood as posing” (by Jan Cohn, from “Romance the Erotics of Property”, 1988, p24).

This is all so that fairytale erotics of captivity, and the DatM dynamic itself, can freely dance around the guilt of being an active participant in desire, and all the consequences that can come with it. Looking at Death in abstract, or his beastly counterpart, he is a contradiction of desire, both psychically and semiotically. Intensely repelling, but also charmingly magnetic. Make no mistake, the Maiden’s disgust of him is a mock-passivity. It is active desire in a trench coat. In framing sexuality as looming, beastly threat, the shame of desiring can largely be sidestepped, as it can be “forced” upon her. This sort of irony softens the burn of public desire, a sort of prescribed nonchalance that lessens the intensity of being caught wanting. Beauty humbly never wants for anything except a single rose, but gets everything regardless.

“To have a wound in your leg-that's reality. And everything in her life, from the moment she'd been born, everything in her life had been soft and smooth, like the leap of a cat, like a charade.”

by Clarice Lispector, see Archive Source 3

While Death is easily understood to be dangerous, deadly, he is also a figure of tenderness. The DatM romance operates on the principle that we, as audience, tensely believe his dangers don’t extend to her. My beloved Intersection of Love and Violence is, despite appearances, not a blanket of approval of all things fair in love and war. It is simply a statement of the intricacy in human emotion, my dear. Roland Barthes writes that “it is not violence which affects pleasure, nor is it destruction which interests it; what pleasure wants is the site of a loss, the seam, the cut, the deflation, the dissolve which seizes the subject in the midst of bliss.” (by Roland Barthes, from “the Pleasure of the Text”, 1973, p7).

DatM, BatB, and vampire romances all operate on this golden principle that Death’s violence is always pointed away from the Maiden. “He would never hurt her”. Except, of course, when he does. There are, after all, DatM pairings where physical violence does take place in either direction: Klaus Mikaelson repeatedly endangers Caroline Forbes’ life in “the Vampire Diaries” (2009-2017), Lestat and Louis fight physically in “Interview with the Vampire” (novel 1976, show 2022-), Hannibal stabs Will in “Hannibal” (2013-2015), ditto for Eve and Villanelle in “Killing Eve” (2018-2022), not to mention Rey stabbing Kylo Ren in “Star Wars: the Rise of Skywalker” (2019).

Perhaps this interest in stabbings and [vampire] bites is interesting to take note of, as they are both a distinctly penetrative act. Consumptive, even, in the case of the vampire, or the Beast that Beauty fears will devour her. The DatM romance has sharp edges, it is messy. Unsafe. The ecstasy of eroticism is the antithesis of the comfort zone. It brute-forces transgression, transmutation, and eventually transformation.

Bataille argued that the taboo of death and the taboo of violence together create a fascination with the corpse: a mix of interest and disgust much like the Maiden’s conflicting feelings for Death. “We are at once repulsed by and attracted to [Death]; we shouldn’t long for Death in this way, because it is the lack of everything we have ever known – death is violent, uncaring, Godless, and cruel, the opposite of all that life should represent. But at the same time, Death is secure and promising. Why shouldn’t we embrace what we are, what we will become?” (see Newsletter 13, Archive Source 3). Our interest is piqued when the darkness looks back at us, no matter the horror it might inspire.

The Maiden also often brings out a more human aspect in Death. In “the Vampire Diaries” (2009-2017) a scene of the villainous vampire Damon (Death), gently touching human Elena’s (the Maiden’s) cheek as she sleeps is overlaid with his brother journaling in torment over Damon’s moral bankruptcy. “But [I] was wrong, there's nothing human left in Damon. No good, no kindness, no love. Only a monster... who must be stopped.” (S01E03 “Friday Night Bites”)— which is obviously visually juxtaposed with his growing tenderness for the Maiden Elena, for which he will later endeavour to change his ways.

Previously discussed4 big bad of the same show, Klaus Mikaelson, also gets his own DatM romance, though without fulfilment, with the newly turned vampire Caroline, who muses about the transformational effects of love: “I know that you’re in love with me. And anybody capable of love, is capable of being saved” (S04E13 “Into the Wild”). Though Klaus’ status as rotational villain of “the Vampire Diaries” (2009-2017), and later anti-hero of spinoff show “the Originals” (2013-2018) obviously prescribes that he can never be fully cured of his villainous ways or past, in order to facilitate the plot.

This doubling of villain and romantic hero is becoming status quo in the modern romance novel, Jan Cohn posits in his book “Romance and the Erotics of Property” (1988). Whereas the Victorian novel often had a stale, “good” hero, and a sexually seductive, threatening villain, popular romance has more often now folded these two figures into themselves to create a new hero who is, at the offset, both morally grey and sexually enticing, but through the course of the plot will be redeemed by love, and “tamed” to some extent. All the violent, anti-social, brooding tendencies will be either killed off or reshaped in service of the heroine, the Maiden. Male aggression tamed in the service of love.

Though this is not to be mistaken for a total de-clawing of Death. Modern romance tropes like “he hates everybody but her”, “grumpy x sunshine”, or “touch her and you die” all relish in keeping the hero’s “bad” side around and neatly boxed up to be dusted off and brought out whenever the story needs a fresh injection of [erotic] excitement. Appropriate fare for a generation who largely felt that Beauty looked a bit… dejected in seeing her Beast’s transformation in the 1991 animated Disney classic.

“The transformed or tamed (read “humanized”) prince is not nearly so memorable as the Beast, a figure of power and vulnerability combined. That is a rich combination of natures. It is the Beast as beast who rivets attention and burns the story into one’s mind. It is the Beast on whom storytellers, writers, and artists focus their imaginations. The climax of the story is Beauty’s love of the Beast himself, not the transformation and marriage, which is anticlimactic if pleasant. Therein lies the great disappointment of many graphic and literary conclusions of “Beauty and the Beast.” The prince seems bland in contrast to the powerful reconciled beast; he is in fact anticlimactic to the forceful struggle of balancing beauty and beast.”

by Betsy Hearne, from “Beauty and the Beast: Visions and Revisions of an Old Tale” (1991)

Marina Warner refers to the tension between Beauty and Beast as “the seduction of difference” (from “From the Beast to the Blonde”, 1994, p272), but the kicker is that they are not as different as they seem after all. They each see concepts in the other that they wish to assimilate to, or nurture. “[…] what the wolf loves in the lamb is its own goodness.” (by Hélène Cixous, from “Love of the Wolf”, 1998) What Bella seeks in Edward (“Twilight”, 2008) is to appropriate a bit of the supernatural world he inhabits, the excitement his vampiric nature brings. Edward, in turn, relishes the normalcy and fragility of the human Bella. Her soul. This is what their tension throughout the saga amounts to; for either one to get their wish is for the other to sacrifice theirs. Which is why Edward, as “post-feminist” “perfect masculine”5 figure eventually succumbs to Bella’s wishes.

Tamed Death, the vampire boyfriend, and the modern romance hero are expected to contain “every positive aspect of masculine privilege, without personifying those more threatening facets of hyper-masculinity — the violence or the uncontrolled sexuality.” (by Ananya Mukherjea, from “My Vampire Boyfriend: Postfeminism, "Perfect" Masculinity, and the Contemporary Appeal of Paranormal Romance”, 2011). In a sense, they exist as a puzzle box for the Maiden, for the reader. A problem to be solved. They are a lack, an absence, a malnourishment. An “affliction”, per “Nosferatu” (2024). Perhaps this is the allure of Death, that which the Maiden is drawn to all along. In inhabiting an ever-shifting semiotic space, Death becomes largely congruent with Lacan’s idea of the woman, as we have seen before. This is how Death can exist as hyper-masculine, and simultaneously be feminised as Other. And through the fairytale gaze in particular, Death in the form of Beast, is then able to be neutralised narratively precisely because of this ever-shifting meaning6.

“When women tell fairy stories, they also undertake this central narrative concern of the genre – they contest fear; they turn their eye on the phantasm of the male Other and recognize it, either rendering it transparent and safe, the self reflected as good, or ridding themselves of it (him) by destruction or transformation. […] moving from the terrifying encounter with Otherness, to its acceptance, or, in some versions of the story, its annihilation. In either case, the menace of the Other has been met, dealt with and exorcized by the end of the fairytale […].”

by Marina Warner, from “From the Beast to the Blonde” (1994), p276

II.VI Dream-walking / Death-walking

“And lo, the maiden fair did offer up her love unto the beast and with him lay in close embrace until the first cock crow. Her willing sacrifice thus broke the curse and freed them from the plague of Nosferatu.”

quote from “Nosferatu” (2024)

Previously, we discussed the “beautiful dreamer” trope and its enmeshed relationship with the DatM trope and vampire romance, but there is another nighttime trope oft-associated with DatM which has gone overlooked: sleepwalking, or, somnambulism. Ever since Bram Stoker’s “Dracula” (1897), sleepwalking has always had a place in the pantheon of DatM-related motifs, calling to mind Lucy sleepwalking and meetings with the monster. Scandalous and erotically charged.

Count Dracula noticeably attacks his victims asleep, or in the space between slumber and wakefulness, when it is understood that they are at their most fragile. Sleepwalking is the ultimate vulnerable state, my dear. A representation of the Maiden’s mortal fragility in comparison to the immortal force of Death. Like ecstasy, jouissance, or Bataille’s eroticism, it is a representative dissolving of human identity, a chasm where reality and unconsciousness meet. It is a state between life and death. When Lucy’s sleepwalking intensifies again in “Dracula” (1897), weeks before the Count even sets foot in Whitby, we as readers are meant to understand that it is her symbolic wandering towards death. The call of the underworld. A sign of an unstable, volatile nature. Trouble is brewing and it has marked Lucy, God help her soul.

Similarly, unauthorised “Dracula” (1897) adaptation “Nosferatu” (1922) took this idea and let its Mina, named Ellen, sleepwalk on the edge of balconies. Quite literally the brink of life and death. Like in “Dracula” (1897), Ellen / Mina has a spiritual, even psychic connection to Count Orlok / Count Dracula. Robert Eggers’ subsequent 2024 adaptation takes this idea and runs with it. Ellen’s dreams and her sleepwalking are big plot points, alerting us to the sense that something is off. “He is coming, he is coming!” she murmurs in her sleep, carefully building the film’s horrific sense of dread. Like Mina, she is marked for death, for Count Orlok, who is almost explicitly a figure of Death with a capital D, a harbinger of plagues and darkness personified. We are told over and over again that Ellen is the perfect mark for Orlok, his “pretty bride”; “Demons like those whose lower animal functions dominate”. The woman mystic.

“Dracula” (1897) is a story of modernity in conflict with folk tradition; the Count preys on the “modern” people of London precisely because they have gotten lost with the rites and rituals that could kill him. They are easy targets, ripe for the slaughter. Lambs of God and industrialisation, weak to his ancient ways. “And yet, unless my senses deceive me, the old centuries had, and have, powers of their own which mere ‘modernity’ cannot kill.” (by Bram Stoker, from “Dracula”, 1897). “Nosferatu” (2024) in turn unfolds Ellen’s character to be a deeply emblematic and spiritual woman who “would have made a great priestess of Isis in heathen times”, or so she’s told. The [Lacanian] woman is undefinable, in-between, and Ellen is the manifestation of this idea, being literally caught in-between times, a victim of a tug of war between modernity and old tradition. Professor Von Franz (Van Helsing) tells her: “I am but an able tourist in this occult world. You were born to it. It is a rare gift.”

Ellen goes beyond the sleepwalking trope into near-hysteric, excessive, rapturous “episodes”, complete with bodily convulsions and other dreadful accoutrements. Death has marked her, and he is coming to collect. Even when the DatM story does away with the sleepwalking, it likes to infest its Maidens’ dreams with the influence of Death. Mina dreams of the Count, the vampires in the TVDU (“the Vampire Diaries” universe, including its spinoff shows) can manipulate dreams, Sookie in “True Blood” (2008-2014) dreams plenty of her vampire suitors over the course of the show, Laura dreams of Carmilla in “Dracula” predecessor“Carmilla” (1872), and Beauty dreams of the Beast in the original tale.

These dreams are often erotic in nature, if not outright sexual representations of the Maiden falling under Death’s spell. Almost as if that half-conscious state is a segue, a river Lethe, a place between life and death where the Maiden and Death can meet, free of the physical consequences of their fraught union. Though this certainly does not make it a level playing ground, my dear.

“Certain vague and strange sensations visited me in my sleep. The prevailing one was of that pleasant, peculiar cold thrill which we feel in bathing, when we move against the current of a river. this was soon accompanied by dreams that seemed interminable, and were so vague that I could never recollect their scenery and persons, or any one connected portion of their action. But they left an awful impression, and a sense of exhaustion, as if I'd passed through a long period of great mental exertion and danger.”

by Sheridan le Fanu, from “Carmilla” (1872)

Perhaps this pattern of sleepwalking and dreams is also a testament to our weakening defences as we fall asleep; when we lay our head down to rest, we are preparing for a journey into a world unknown. A world ever changing, sometimes hostile and sometimes amiable, but always unknown. We can never know what awaits us when we close our eyes. It is the ultimate disarming of the spirit, the ultimate submission of mind, the ultimate erotic ideal of anticipation. Sleep, in general, is loaded with erotic connotation, as the bed is easily equated to the marriage bed. Which, in turn, is easily a deathbed. Bataille wrote about eroticism as the momentary death of the self (“Eroticism”, 1957), the interruption of self as discontinuous being and a contact with the continuous. The vampire, Death, is continuity taken flesh. Immortal in form, transcending time and space through ancient customs and rites, living under the hazy law of folklore rather than the law of men. Therefore, the union of Death and the Maiden is textbook eroticism.

The vampire's encroachment on the mind is another erotic violation— it is not enough for Death to have the Maiden's body, he hungers for her mind and soul as well. Complete enmeshment, a cannibalisation. As long as there are sanctuaries he shall not rest. The vampire consumes life (energetically) through blood, and Death consumes life (literally) through death. Then, what is the dream to the vampire? What purpose does Death seek in somnambulism? What new frontier is breached in the Maiden’s subconscious?

Perhaps the answer is lust, or rather, desire. Dreams get under the skin in a way that nothing else can. In “True Blood” (2008-2014) humans who drink vampire blood experience more frequent, erotic dreams of the vampire in question. Analysing Freudian attitudes to the dream, Ernest Jones writes that “a repressed wish for a particular sexual experience may be represented in a dream by imagery which, though associatively connected with them in the unconscious, is very dissimilar in appearance to the ideas of that experience: or, on the other hand, the ideas may appear in the dream, but accompanied by such a strong emotion of dread that any notion of their representing a wish is completely concealed from consciousness.” (from “On the Nightmare”, 1951). The contents of the dream are secondary to their purpose; the liberation of repressed desire. And repression is certainly a large part of the Maiden’s attitude towards the taboo Death represents: “Don’t you get it? [He] is my shame. [He] is my melancholy / He stalks me in my dreams. All my sleeping thoughts are of him every night.” Ellen admits in “Nosferatu” (2024).

What the subconscious wants and the conscious chases are often different things. Ego and id in conquest. Whereas Freud posited that all dreams fulfilled a subconscious desire in some way (“the Interpretation of Dreams”, 1899), Jung saw the dream as a fence-post for conscious lack. The difference in philosophy means the dream is either a processing of the unaware, versus a nightly theatre of unmasking. Whichever you subscribe to, desire is still front and centre. Of course the vampire, a creature entirely of consumption and want, cursed to never be fully satiated, would use a weapon crafted for desire in its vicious games. Death hungers.

Dreams feature heavily in the vampire mythos. Stephanie Meyer dreamed up the idea for “Twilight”, complete with sparkle and all. Ernest Jones points out that “the belief that the dead can visit their loved ones, especially by night, is met with over the whole world” (from “On the Nightmare”, 1951). The dream as un-reality, as land of pure uncanny, governed solely by imagination, is the perfect meeting place for the unimaginable. It can be bent by will to be anything, depict anyone, serve any purpose. It is the ultimate servant to Death’s desires. This complete brute-forcing of the human will is another hallmark of the vampire story: hypnotism, “compulsion”, or “glamours” are very often present. Yet another way that the Maiden is weak to Death’s influence.

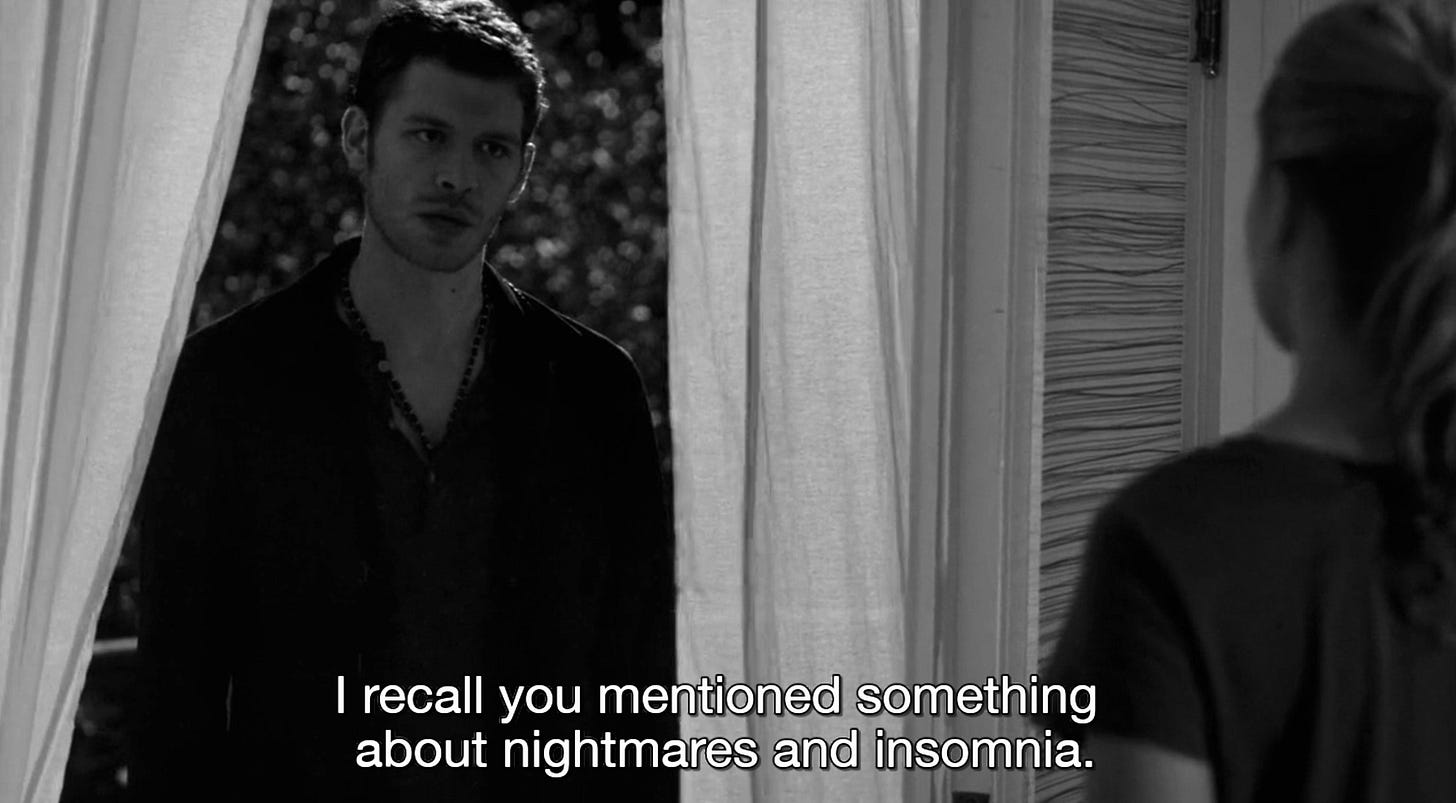

Excuse me for parading my darlings around yet again, but I would be remiss in excluding a second Klaus Mikaelson ship from “the Originals” (2013-2018) from this piece. Because where Klaus’ dalliance with Caroline in “the Vampire Diaries” (2009-2017) is one of a thousand year old Original vampire (think; special vampire7) and a newly turned “regular” vampire, his relationship with Camille in “the Originals” (2013-2018) is much closer to a true DatM representation. It ticks all the boxes; Klaus is a representation of Death, of male sexuality, violence, and power. Whereas Cami as Maiden (and as therapist by occupation) is caring and empathetic towards him, equally intrigued and repulsed. A signature scene of their unfolding push-and-pull romance happens when Klaus shows up to Cami’s apartment, looming in the folds of her white curtains flowing in the wind. She invites him in, and he uses his vampiric powers of mind compulsion to force her to forget her trauma surrounding her brother’s death, and in turn, to “sleep and […] dream of a world far better than this one. A world where there is no evil, no demons, and all people desire only to be good.” (S01E04 “Girl in New Orleans”)

Unlike the vampire as cause of somnambulism, here vampiric presence is instead a brute-force cure for nighttime disturbances. It is a clever reversal of the vampire-as-nighttime-disturbance trope, at least in part— Klaus’ influence on Cami’s mind is not welcomed by her. When she eventually dies, the show ticks another DatM box by making explicit all the ways in which the Maiden has transformed Death. On her deathbed, Klaus tells Cami: “You stayed my hand... [you] quelled my rage. You inspired goodness in me... and unlike all of the souls I've encountered and forgotten in the long march of time... I will carry you with me.” (S03E19 “No More Heartbreaks”). In her own way, she is granted a kind of immortality.

Free will is a large part of the vampire mind control trope (as I’m going to refer to it, for the sake of brevity), as it is the hinge of the audience’s suspension of outrage, an acceptance of the skewed power dynamics at hand. This half-illusion of informed consent must be maintained to keep all the other fantastic liberties of the story in check: mind control must not be used to force the Maiden’s hand, at least not romantically. All other uses of these gifts to bend her to the vampire’s will are grey area, on which you’ll find opinions are widely divided. Damon’s (“the Vampire Diaries”) abuse of Caroline (when still human) is a hot button topic in the TVDU fandom, precisely because it carries a sexual undertone; he sleeps with her under influence of his compulsion, and we are explicitly shown a scene of her begging in fear8, in her nightgown, and set within her bedroom, which ominously fades to black, leaving far too much to the imagination. Or rather, enough for the debates to be on-going.

If a piece of vampire media wants its romance to be beloved, it is better to tiptoe around the idea of any tampering with the heroine’s free will: “Twilight” (2008) briefly plays coy with the idea (“I'm the world's most dangerous predator. Everything about me invites you in: my voice, my face, even my smell.”) before later instalments turn Bella into the ultimate immunity-shield against any and all vampiric powers. Sookie in “True Blood” (2008-2014) is immune to vampiric glamours, and good guy Stefan simply refuses to use compulsion on Elena in “the Vampire Diaries” (2009-2017), even gifting her a necklace containing the one herb that can protect her against it.

In the end, the Maiden has to go willingly to Death. Beauty must make her own journey into the jowls of the Beast. Any victory won unfairly in love is hardly one at all.

“Young soul, put off your flesh, and come / With me into the quiet tomb, / Our bed is lovely, dark, and sweet.”

by Thomas Lovell Beddoes, from “the Phantom-Wooer” (1851)

III. Notes for an Anniversary

“When a woman has scholarly inclinations there is usually something wrong with her sexuality.”

by Friedrich Nietzsche

Two years, and tens of thousands of words into this magnificent journey, I wish you a happy second anniversary of this Substack! As always, I very much intend to keep the extravagant well-wishes for the Society’s anniversary in October, but I do want to use this little corner of the letter again to thank you, my dear. As much as I jest about “locking myself in my attic” every month to write, it truly makes me feel less apathetic, and much more alive. Paradoxically, cozying up to Death, to the Intersection of Love and Violence, has been an innately healing practice for me. And there’s never been anything more rewarding than seeing how many people get it.

Thank you, truly, for reading my words (especially these long DatM, diatribes), for engaging with them, and for sending in your own! It’s a never-ending honour to be able to share my monthly hyper-fixations and ramblings with you, and to get to do so with such an understanding, respectful, ghoulish audience. In the best way possible. Together we have built a community where jokes about “Twilight” (2008) can live next to theory by the likes of Bataille, Lacan, and Baudrillard. Just as it should be.

And it wouldn’t be half as lovely without you. ૮꒰ ˶• ༝ •˶꒱ა ☆୨ৎ

✧・゚: *✧・゚:* On the List *:・゚✧*:・゚

Exhibitions, Events, and Talks. First and foremost, the “London Month of the Dead” events went live this past month— do make sure to check them out if you somehow missed it, or sign up to their mailing list to snag tickets to their highly coveted October agenda of events. The White Lily Society’s favourites for this year are the “Necrophilia” talk on the 12th of October, “Gothic Angels of Death: Mourning, Memory and the Feminine Gothic in the Cemetery” on the 16th, “The Mourning Trade: The Rise of the Funeral Director in Victorian Britain” on the 18th, the “Death and the Maiden” concert on the 18th, and their evening of silent short horror film adaptations of Edgar Allan Poe on the 24th. Best to book in advance, my dear!

Then there’s this month buffet: a Woman Becomes a Wolf returns with another foray into poetry and performing arts tonight, the chess club Bataille is having a silent opening on the 6th, bound to be scandalous and cerebral, Alannah Cyan is celebrating the launch of her new photobook / pseudo-bodybuilder magazine about control and devotion on the on the 7th, Ethereal Maison is hosting a salon of artwork until the 9th, and beloved indie brand Rabbit Baby is having a selection of artists celebrate their newest collection on the 26th.

Film, Music, and TV. The BFI has been keeping its line-up sun-drenched, and thus inappropriate for us vampires and other creatures who snarl at the sun. But if one is still up for a satirical comedy in which Nicole Kidman plays a weather-girl driven to murder in pursuit of fame, they are screening 1995’s “To Die For” on the 2nd and 23rd, or with intro on the 13th.

As for re-releases, Picturehouse has a dazzling line-up prepared for August, starting with the erotic mystery film “the Handmaiden” on August 2nd, the classic Marilyn Monroe comedy “Gentlemen prefer Blondes” (1953) on the 2nd, 3rd, 6th, and 7th, as well as Dario Argento’s technicolour nightmare “Suspiria” (1977) on the 23rd, 24th, 27th, and 28th.

Picturehouse is also continuing it’s David Lynch tribute line-up, screening his short films starting August 1st, hosting “Twin Peaks” (1990-1991) season 1 all-day marathons starting on the 9th (with intro on the 3rd), and screening “Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me” (1992) starting August 15th, as well the “Lynchspiration” “Experiment in Terror” (1961) from the 16th. Last but certainly not least, Deeper Into Movies is screening cult-classic blue-drenched coming of age drama “Thirteen” (2003) at Farr’s Dalston on the 23rd. Tickets start at £5.

Lovers of the strange and unusual can also rest easy, as Netflix’ “Wednesday” returns for part 1 of Season 2 on August 6th. Part 2 is due to be released on September 3rd. The tail-end of the month is also looking to be one of musical polarities; Ethel Cain’s sophomore album “Willoughby Tucker, I’ll Always Love You” will be released on August 8th, while Sabrina Carpenter’s already infamous “Man’s Best Friend” will come out of hiding on the 29th.

In the Stars. August’s full moon on August 9th is also known as the “full sturgeon moon”, “harvest moon”, or “storm moon”— an indicator of seasons changing, finally. The majority of the month is taken up by Leo season, perfect for all things dramatic, devoted, or decadent. If you wish to cast a spell and invite extravagance into your life, the best day to do so will be on the 11th, when six planets are in alignment: Mercury, Jupiter, Venus, Uranus, Neptune, and Saturn. Truly a magical occurrence.

Obsessive Tendencies: What I’ve Loved Lately

Sunday 1994, “Car Chase” t-shirt, [I am truly blessed that one of my favourite bands has such cute merch], $33

Maybelline, Superstay Matte Ink Liquid “50 Voyager”, [The lipstick I wore to see Dita von Teese in “Diamonds & Dust”; a luscious deep brick red], £10.99

Lush, “Sticky Dates” shower gel, [The most scrumptious vanilla scent], from £6.50 (70g)

Lush, “Sticky Dates” body spray, [Perfect to layer and make the vanilla sweetness last all day]. £28 (200ml)

Victoria’s Secret, “the Wink” Black Balcony Lace Push Up Bra, [I refuse to wear anything but black lace, ever], £35

Edward Gorey, “The Gashlycrumb Tinies” (Collector's Edition), [A perfectly macabre bedtime story; “A is for Amy, who fell down the stairs. B is for Basil, assaulted by bears” etc.], £12.99

“I fell in love with the idea that the mysterious thing you look for your whole life will eventually eat you alive.”

by Laurie Anderson

And so, my arduous yearly journey comes to an end once more. That my desk and my mind have not collapsed in yet with the weight of all these books, all this research, all these references, is a minor miracle. I fear I am always using these farewells to report on animals in my house, like a harbinger Disney princess, utterly obsessed with omens. Regardless, here is last month’s tally: one moth infestation-turned-hoax, two tiny mice caught and released, and one stray pigeon rescued off my roof and given a brief house tour. She was entirely unimpressed with my choice of decor. Upon catching said pigeon, I was told by an animal shelter volunteer that being “a little bit psychic” would help. The Achilles heel of a London pigeon is apparently (and bizarrely) the human intuition.

This month ahead, this gorgeous August, will be a bit crushing perhaps. My plate is ever too full for my appetite, voracious as it can be. I am aiming to be overloaded with meaning. To re-imagine all the chaos as Dionysian. For now, I leave you these final words:

“Do you know what it means to be loved by Death? No pain.”

from AMC’s “Interview with the Vampire” (2022-), S02E2 “Do you know what it means to be loved by Death?”

Until my next letter,

With love (and violence),

x Sabrina Angelina, the White Lily Society 𐔌՞. .՞𐦯

Currently reading: “On Mysticism: the Experience of Ecstasy” by Simon Critchley // Most recent read: “Beauty and the Beast: Classic Tales about Animal Brides and Grooms from Around the World” edited by Maria Tatar

White Lily Society links // Sabrina Angelina links

Whether you identify as Death, or as Maiden, the White Lily Society is the place for you. Here, the Beast dances with Beauty. Terror converges with divine, Faustian knowledge. Vampire boyfriends are welcome on the proverbial premises. So, join us, and become a martyr of deliciousness.

📼 Song of the (past) month: Nettles - Ethel Cain

Full 2000 page motif index available on the Internet Archive for your perusal.

At least, looking at myths like “Zeus and Europa”, or the animal brides and bridegrooms we will be familiar with later.

See also, DatM II. Yes, I will bring Klaus Mikaelson up to anyone who listens. Having a captive audience is just so wonderful!

See Ananya Mukherjea, “My Vampire Boyfriend: Postfeminism, "Perfect" Masculinity, and the Contemporary Appeal of Paranormal Romance”, 2011 - link