20. Once Upon a Dream

Best to avoid the spinning wheel, my dear.

“Now I think life kinda begins in March. January is just nostalgia and recollection. And February- it's all about regaining consciousness.”

by Zugen

TW. Because this newsletter does recount the original “Sleeping Beauty” seventeenth century tale (Basile), so there is a brief mention of rape included, as the story involves a non-consensual relation with one party in a magic sleep. Please note that this is only a mention, and not any in-depth description or the likes. To skip this part entirely, skim over parts of section II.I starting at “Now, the story progresses” until “Nine months later”. Other parts of the newsletter involve conversations about consensually skewed power dynamics etc.

01/03/2025, London, UK

My dear,

Once upon a time, there was a girl, locked away in her attic room, overlooking the sunset, writing to you now. With her hair braided and pinned with ribbons, and stacks of books on her desk so high they almost hit the ceiling, she has laid out her careful buffet of tenderness. Some might call it a shameful indulgence of desire, but hush, it is me that is narrating this story, and not them. In similar fashion there is a dove nesting in my windowsill, stubbornly trying to dictate to me what to write— but I shan’t listen. I won’t. My fancies are symbolically potent only when it serves me.

It would be easy to spend a whole life, just sitting and waiting. Dreaming, wasting days in excess, and languor. Instead of chasing the beauty and virtue, to let them come to you. Hear the wings flutter and the ideas coo. Here, open your palms, press the seeds of sweetness into them, and wait for the little ones to scuttle on over to you. Alas, a life lived only in castle walls is a life wasted, so I think the best medicine for a sceptic heart is to read more fairytales, my dear. To become more floaty, dreamy, otherworldly. Why ever did we lose this ability as we grew up? Regardless of reason, this here letter is intended to be a fortifying injection, a magic potion, a secret that tastes of violets and sage. Once you read it, it’ll grant you any wish.

Just to speak more plainly: this newsletter is all about fairytales, or rather, it is all about “Sleeping Beauty”. It touches on female submission, eroticism, and beauty standards in fairytales. But if you have an ogre’s appetite for these weavings of fascination, and I know you do, rest assured! March is looking to be a month chock-full of fairytale feasts for the White Lily Society, with an offering to exceed even your voracious hunger. Over the course of the next month, there will be much more ado about fairytales happening both here and on Instagram, especially as the assortment of related submissions starts being posted— so keep an eye, or two, or three, open for that.

So, without further straying from the path, let’s continue our story…

This newsletter contains the following sections:

I. Archive Sources // II. Beauty: asleep, eternal, liberated // III. Museum Recap: February // “On the list: March” // Outro

I. Archive Sources

“[A]rchetypal stories, fairy tales, myths, fables and legends always work. You can always see yourself in them. And these are the stories that get told repeatedly. We tell “Hansel and Gretel” to our children and go to see “Oedipus” and “King Lear” on stage because they always work. You don’t need to bend it and reshape it to talk about now; it becomes now.”

by Robert Eggers, from an interview with Salon (2024)

Now, now, don’t be so hasty in straying from the path! Remember, one much always pay their respects, even when making their way to excitement. We must first properly set the scene. There’s a reason all fairytales start in describing their lands of unknown whimsy, no matter how brief. Consider some of these readings your set dressing, your introductory phrasing, your “there once was a kingdom”… Easily skipped over, but all the more enchanting if you do indulge.

“The Pervasiveness and Persistence of the Feminine Beauty Ideal in Children's Fairy Tales” - link

That beauty in fairytales is often associated with youth, goodness, whiteness, and economic privilege, is common knowledge— but just how much is that message reinforced through the reproduction of the fairytales it inhabits? This study found that, statistically, the greater the focus on the beauty of the female characters is within a fairytale, the greater the likelihood is of it being reproduced throughout the years. The study makes a point to link this increased importance of internalised female beauty standards to greater social freedom for women; as women gain rights and their dependency on patriarchy (theoretically) wanes, more restrictive beauty standards arise to chain women internally even as they slowly cast of their societal and economic chains.

“Table 1 indicates that women's beauty is highlighted more than men's attractiveness and that beauty plays a more dominant role for younger women than for older ones. Overall, there are approximately five times more references to women's beauty per tale than to men’s handsomeness.”

““But marriage itself is no party”: Angela Carter's Translation of Charles Perrault's “La Belle au bois dormant”; or, Pitting the Politics of Experience against the Sleeping Beauty Myth” - link

This text investigates both Angela Carter’s translations of Perrault’s fairytales, as well has retellings as found in “the Bloody Chamber” (1979). It essentially argues that Carter’s more feminist interpretations take advantage of the indicative potential for these more modern narratives within these age-old tales. “The text [of Perrault’s Sleeping Beauty] easily lends itself to a feminist reading that mocks the influence of sentimental stories that fool girls into marrying young.” In acting as a “Fairy Godmother” relating her dark[er] tales of sexuality, marriage, and romantic cultural myths, Carter is acting in line with large parts of established fairytale canon. Like Perrault, she instills her tales with morals and lessons to teach her readers something about the world in which they find themselves in: a clear-cut parallel to the history of fairytales as outlined in Marina Warner’s “From the Beast to the Blonde” (1994).

“Some feminist critics have notoriously objected to Carter's use of the fairy tale in “the Bloody Chamber”, arguing that the author merely reproduces the narrative structures and patriarchal models that they see as inherent in classic tales. But this is to ignore the sexual politics of Perrault’s texts as well as their reworking in Carter's translations and rewritings, where the idea of “intellectual development” through the active reading of old text is thematised and enacted. Carter’s productive dialogue with Perrault thus confirms the transmission of unofficial, empowering, as as well as entertaining knowledge against the mainstream recuperation and exploitation of fairytales.”

“Why Fairy Tales Matter: The Performative and the Transformative” - link

Fairytales, this paper purports, are an important transformative tool because they teach us about imagination, and about the power of words leading into action. When, as children, we are read these tales of wonder, we learn a little bit about “magical thinking”, but we also learn that just being good or thinking pretty thoughts is not enough to get us by. The rules of the world are distorted in such a way that we can begin to grasp the basics of it, but the rest we will have to do ourselves. Cycling through a whole list of references, films, authors, commercials, and books, this paper succinctly and briefly illustrates why fairytales still have a hold over us, all these many centuries later— and why they probably will continue to do so, for a very long time.

“In the enchanted world of fairy tale, anything can happen and what happens is often so startling, magical, and unreal that it often produces a jolt. Shape-shifting, as Marina Warner has pointed out, is one of the defining features of fairy tales, and it happens in ways that invariably contradict the laws of nature […].”

II. Beauty: asleep, eternal, liberated

“Isn't the function of a good fairytale to instill fear, trembling and the sickness unto death into the existential virgin, anyway?”

by Angela Carter, from “the Better to Eat you With” (1976)

All fairytales can be boiled down to a list of tale types, tropes, and motifs— or so I’ve learnt. It turns out the academic classification of folklore is quite an extensive field! Who could’ve known? As I started my enquiry into these fairytales, which then rapidly transformed itself into an in-depth exploration of just “Sleeping Beauty”, I found a great array of databases out there aiming to simplify and streamline the study of fairytales. One of the major ones is Hans-Jörg Uther’s 2004 “the Types of International Folktales: a Classification and Biography”, which labels our beloved Sleeping Beauty as a tale type ATU 410 of the same name. Following that, we can find some of the prevalent motifs in tales of this type around the world, sourced from the extremely extensive “Thompson Motif Index of Folk Literature”1. These key ingredients include, but are not limited to:

(M341 Death prophesied) M341.2.13 Prophecy: death through spindle wound.

D1364 Object causes magic sleep

M370 Vain attempts to escape fulfillment of prophecy

D1960.3 Sleeping Beauty. Magic sleep for definite period

N711.2 Hero finds maiden in (magic) castle

D735 Disenchantment by kiss // D1978.5 Waking from magic sleep by kiss

Any Sleeping Beauty variant might contain any number of these prevalent motifs, or all of them. The kiss, which has come to be synonymous with the story, actually doesn’t appear in all of the key stories! But I am running way ahead of the charge here, my dear. Do forgive me. For our beginning inquisition, we shall first be journeying through the three most well-known versions of the tale, which will take us all over Europe. First to Italy, for Giambattista Basile’s original tale from the seventeenth century, then to France to see Charles Perrault reinterpret it, and finally, to the brothers Grimm in Germany, before scuttling off to talk about submission, beauty, and liberation. Quite the full agenda.

II.I Poor Aurora / Sleeping Beauty

“Till then, Sleeping Beauty, sleep on

One day you'll awaken to love's first kiss”

from Disney’s “Sleeping Beauty” (1959)

The original mythical ingredients of “Sleeping Beauty” as we know it bare a startling resemblance to our other beloved fairytale, “Snow White”: you might be forgiven for imagining them long-lost relatives, with their shared sleeping spells and curses. In fact, in the original Italian version of Sleeping Beauty (called “Sun, Moon, and Talia”, 1634-1636) written by Giambattista Basile in the 17th century, there are the usual king and queen with an ardent wish for a child, unsuccessful in their many attempts. Their wish is, after many years of yearning, fulfilled, and they are blessed with a beautiful daughter, a princess. Wishing eagerly to know of their long-awaited daughter’s fortune, the king and queen consult a royal astrologer, who tells them of the terrible fate awaiting their filial love; she is to invoke great danger by pricking herself on a splinter of flax. Distraught, the king of course forbids that any such fibre enters his house. There shall not be any spinning of flax within his stately walls. It matters not: a fate foretold is a fate half underway. Years pass before the prophecy does, and young Talia, as she is called, finds herself at home alone, gazing from her window to see an old woman spinning flax fibres into thread out in the streets. Emboldened by curiosity, the young princess investigates, and in the process gets a small flax fibre stuck under her nail, at which point she collapses, presumably dead.

Now, the story progresses, and dear Thalia is abandoned, “seated on a velvet throne under a dais of brocade”. The king and queen, unable to live with their grief, set off for greener pastures, or mere oblivion, leaving the castle and their daughter behind. The dust settles on Talia’s sleeping form. More years pass, and another king is entranced by the abandoned castle beyond the hills, calling out to him in its resplendent vacancy. Up in one of the far rooms, he finds Talia, and enchanted by her beauty, he rapes her sleeping body:

“At last he came to the saloon, and when the king beheld Talia, who seemed as one ensorcelled, he believed that she slept, and he called her, but she remained insensible, and crying aloud, he felt his blood course hotly through his veins in contemplation of so many charms; and he lifted her in his arms, and carried her to a bed, whereon he gathered the first fruits of love […]”

by Giambattista Basile, from “Sun, Moon, and Talia” (1634-1636)

Nine months later, this Beauty, while still asleep, gives birth to twins, one boy and one girl. But then, in a turn very reminiscent of “Snow White”, the children, in trying to breastfeed, instead suck on Talia’s fingers, eventually dislodging the piece of flax, and waking her up. She names her newfound children “Sun” and “Moon”. What she doesn’t know is that the King who took her for his lover is already married, and his queen is wondering where her husband wanders off to in the middle of the night, whose names he whispers in his sleep… A secret can never stray far from those with the resources to hunt them down, and so the castle is promptly found, and little Sun and Moon are summoned to court by the queen while the king is out. Enflamed by her husband’s infidelity, the queen orders her cook to kill the children, so that she may serve them to her unknowing husband and have her revenge. But the cook is not about to risk his immortal soul engaging in murder; he orders his wife to hide the children, and instead prepares two lambs, which the queen gleefully serves to her husband in a feast that night.

But of course, revenge is rarely as satisfactory as one imagines it will be. Next, the queen calls for Talia to be summoned to the palace, intending to confront her and then serve her the same fate as her two children. Even as Talia tries to explain what the king had done to her- that the infidelity was cruelly cast upon her in her sleep- the queen holds steadfast, ordering for Talia to be burnt at the stake in the sumptuous palace courtyard. Finally, as she is dragged to her infernal end, the king shows up, and finally learns of his children’s “deaths”; “Alas! then I, myself, am the wolf of my own sweet lambs; alas!”. The very fire that was prepared for Talia becomes the queen’s demise, and as the cook, taken for a foul butcher, a co-conspirator, is about to join her, he confesses his trick. The little children are brought out again, and the king weeps in joy as he embraces them. He promptly marries Talia, and they lived happily ever after.

The story of our dear Sleeping Beauty as we experienced it as children is a lot tamer, and well, features a much lesser degree of nonconsensual stuff. The two main versions stem from Charles Perrault, and the brothers Grimm, and both of them omit large parts and add others. The setup is mostly the same; the king and queen yearn for a child, and are blessed with one. In the Grimm, the queen is uniquely told of this coming daughter by a frog. No, not one who turns into a prince. Juts a regular frog. Then, both tales omit the astrologer and add a gaggle of fairies to attend the christening of this new princess; seven fairies in Perrault, twelve “wise women” in Grimm. Regardless of author, the royal couple has a grand feast unlike any other organised, with pure golden and bejewelled place settings for the attending fairies… All the fairies in the kingdom, except for one, who is understandably disagreeable about her omission from such special festivities.

As all the good fairies, except for one, have bestowed their gifts of grace and beauty and aptitude on the princess, the angered fairy instead unleashes an accursed prophecy, stating that the princess is to prick her finger on a spindle and die tragically. Horror sweeps through the room. But not all is lost: the final fairy still has her wish to make, and utilises it to soften the curse. It will not be death, but sleep, that is cast upon the princess. The desperate king has all the spindles burned in the kingdom, and spinning is outlawed on penalty of death. From this point on, the tales diverge on a lot of the fine details, as well as greater plot points. Major differences include;

In the Grimm, the evil fairy specifies that the princess will be pricked on her fifteenth birthday, while Perrault’s prophecy is vaguer. Perrault’s Beauty just so happens to get pricked “fifteen or sixteen years” later. Both tales insist that her sleep lasts one hundred years, but Perrault’s prophecy includes that a prince will come to wake her.

Both tales include the princess getting pricked because she finds an old woman spinning in a far off tower of the castle. Perrault specifies that she is spinning because the news of the king’s rampage against spinning never reached her.

Both tales include the briars/brambles/thorns, though in Grimm they grow with the time, and in Perrault it is the good fairy’s doing to protect the princess in her slumber. Similarly, in Grimm the curse of sleep spreads through the castle like an infection, and in Perrault it is the good fairy’s intention to put everybody to sleep so that the princess shall not be too distressed when waking up a century later.

Both tales have the prince stumble upon the abandoned castle and inquiring about its legend. In the Grimm, the thorns and hedges also feature many impaled princes who have previously tried to reach the princess for an extra gruesome visual. In both tales, the thorns and briars open to let the prince pass.

In Perrault’s version, the prince simply kneels at Beauty’s bedside to awaken her, having shown up exactly one hundred years after the curse took effect. In the Grimm version, the prince kisses Beauty to awaken her.

Perrault keeps Basile’s extended plot about eating children and evil queens, but because in his version Beauty and the prince get married expeditiously post-awakening, he needs to make a few adjustments. As a result, his queen is the prince’s mother, as well as an ogre, and the little children are eaten one by one before she gains an appetite for Beauty to be cooked next. The queen meets her end in a cauldron filled with toads and snakes, rather than at the stake.

Differences in awakening:

“Trembling with wonder and admiration, he approached and knelt down beside her. Since the end of the enchantment had come, the Princess woke up, and gazing at him with greater tenderness in her eyes and might've seen proper at a first meeting, she said; ‘Is that you, my prince? What a long time you have kept me waiting!’”

by Charles Perrault, from “the Sleeping Beauty in the Wood” (translation by Christopher Betts)

“There she lay, and her beauty was so marvellous that he could not take his eyes off her. Then he leaned over and gave her a kiss, and when his lips touched her, Brier Rose open her eyes, woke up, and looked at him fondly.”

by the Brothers Grimm, from “Brier Rose” (translation by Jack Zipes

A common criticism of Sleeping Beauty, especially the 1959 Disney movie, is within Beauty’s supposed lack of agency. It’s a valid argument, yes, as within the simple conceit of the fairytale itself (“a princess cursed to sleep a hundred years”), she is given the role of essentially an object, put to sleep and awakened at the whims of others. And yet within the limits of the stories’ length and form, Beauty does show curiosity; in the three written versions of the tale, she shows an active interest in the old woman she finds spinning. She doesn't get pricked because she is almost hypnotised and compelled to do so, like in the Disney film, but because she is curious about the old woman’s craft and intrigued enough to inspect this strange activity for herself. In the Disney film too, Aurora is coy and playful, both flirtatious and forward with her prince Philip, and she finds subtle ways to go against her guardian’s (the fairy godmothers) wishes for her. Passivity is a large part of the “scare” of the story, the fright is in being rendered vulnerable and unable to defend yourself, unable to awaken yourself from the terrible nightmare, caught in a spiralling stasis— but it is not the characterising trait of Beauty herself.

It seems, to me, that the Sleeping Beauty story is partly about a fearful lack of control, a sort of mad attempt to outrun the inevitable; the king in his desperation has all the spinning wheels burned and outlawed after the bad fairy delivers her prophecy, all in a futile footrace against destiny. Of course, we (largely) know better now than to believe we can outrun the consequences of our actions, but the fear of the inevitable remains in the prevalent fear of death. The wrestling of control, the tug of war between powers, is present, too, in the quick-fire heat of the prophecy; one minute fine, one minute condemned to death, one minute condemned to sleep; fate is written and rewritten within the blink of an eye. The instigating incident is relatively minor: in both Perrault and Grimm’s version, the fault is one of etiquette and politeness. Control is one of the points of friction within the tale, as its horror is systematically also the horror of being caught unaware. Unprepared to host another guest, ignorant in leaving your teenage daughter alone.

The tapestry of fate will unfurl whether you like it or not, but if you hadn’t dropped some stitches here and there, if the world itself hadn’t tugged at the threads, would everything have been better?

II.II Once Upon a [Semiotic] Dream

“There was a theft. / That much I am told. / I was abandoned. / That much I know. / I was forced backward. / I was forced forward. / I was passed hand to hand / like a bowl of fruit. / Each night I am nailed into place / and forget who I am.”

by Anne Sexton, from “Briar Rose (Sleeping Beauty)” (1971)

Unsurprisingly, fairytales are often ripe for semiotic discussion and fertile ground for erotically charged retellings. They are lands of magic and whimsy, where nonsensical happenings are treated with utmost normalcy, and many of them feature at least some sexual subtext, cleverly tucked away. This is what Angela Carter’s famed fairytale rewritings aimed to reveal, as Carter wanted “to extract the latent content from the traditional stories and to use it as the beginnings of new stories.”. Choosing only the “Gothic tales, cruel tales, tales of wonder, tales of terror, fabulous narratives that deal directly with the imagery of the unconscious” (from the Introduction to the American version of “the Bloody Chamber”, 1971). Sleeping Beauty, though oddly not explicitly part of Carter’s chosen material for her retellings, is especially ready to be transformed in this way. The original Bastile version is dark enough, yes, but the story itself is also perfect for this on the basis of its symbolism alone.

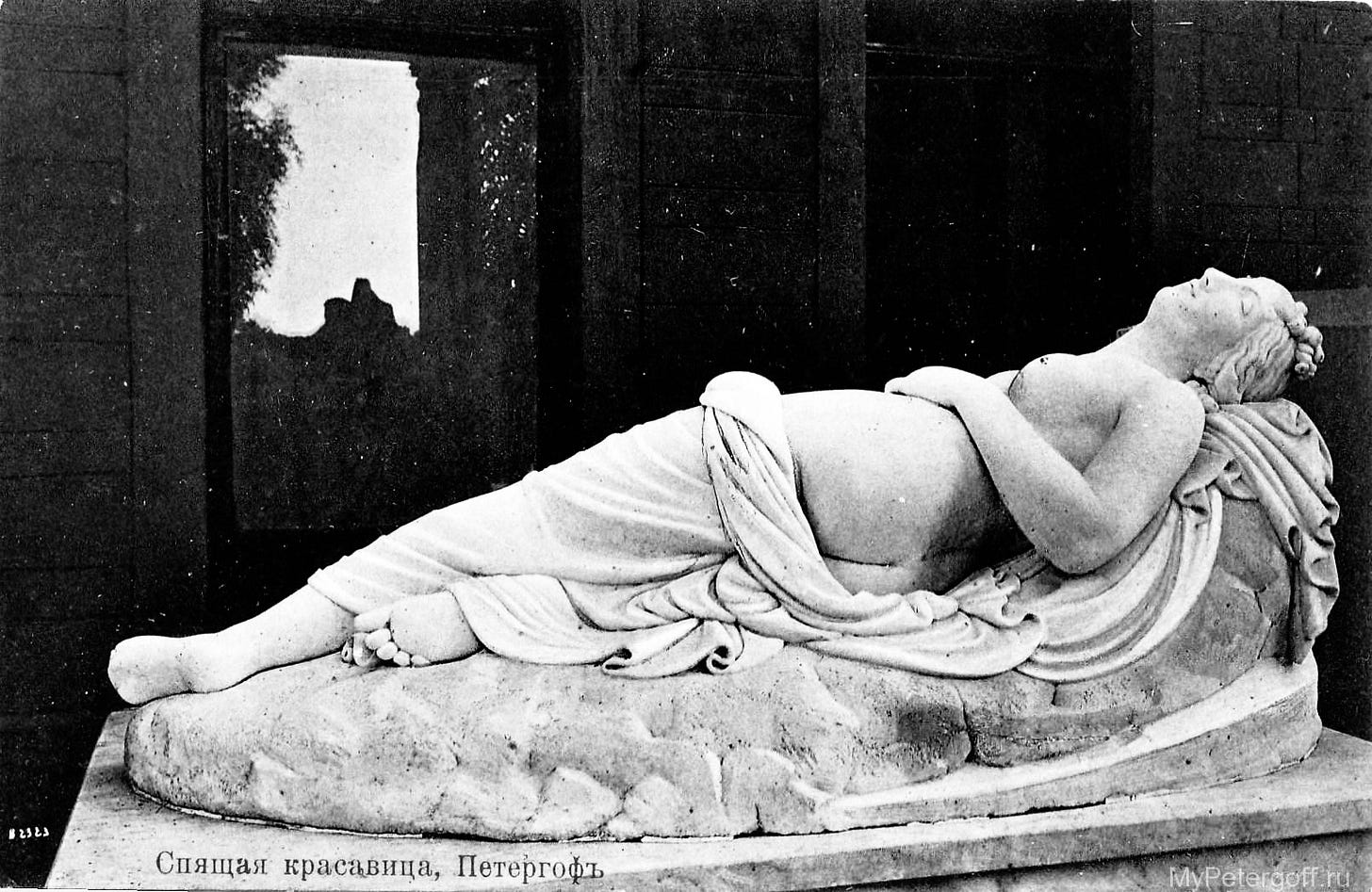

A princess asleep is a princess submissive, is a princess objectified. Bedrooms and beds are, of course, suggestive to the imagination. Sleep is an erotic activity, where our minds disconnect from our sleeping form and wander off into dreams, while our body is wholly subject to the whims of others— at least until we wake up. It is erotic exactly because of this disconnect from the self; Beauty is both erotic object and sacrificial lamb. The magical nature of her slumber renders her uniquely vulnerable; something which Matthew Bourne’s dance production “Sleeping Beauty: a Gothic Romance” (2013) took in consideration for a scene in which Beauty’s sleep makes her a doll for others to manipulate. Beauty is the eternal, frozen virgin protected by the briers that the prince then symbolically pierces through. Whether gently, like in the written versions where the briers part themselves, or with the use of his sword, as in the Disney animation. This “breaking” of the “seal” is deeply symbolic in nature, reminiscent of violation— like in Anne Sexton’s poem “Briar Rose (Sleeping Beauty)” (1971) where Beauty’s curse is tied both to a habitual loss of identity as well as opportunity for incestuous violation. Perrault even hinted at a sexual subtext when he writes that the bushes appear to protect the unconscious Beauty from “curious people”.

“Briar Rose / was an insomniac... / […] If it is to come, she said, / sleep must take me unawares / while I am laughing or dancing / so that I do not know that brutal place / where I lie down with cattle prods, / the hole in my cheek open.”

by Anne Sexton, from “Briar Rose (Sleeping Beauty)” (1971)

(Above: clip from Matthew Bourne’s “Sleeping Beauty: a Gothic Romance”, 2013. The figure reaching for her is the prince, who is, in this adaptation, a vampire. Original Video Source: see production film, filtered B&W)

“Does she experience rebirth as she emerges from silence, or does she enter yet ‘another kind of prison’?”

by Dawn Skorczewski, from “What Prison Is This? Literary Critics Cover Incest in Anne Sexton's 'Briar Rose'“ (1996)

The awakening, then, carries meaning as both a sexual awakening, and an awakening of the identity; in her sleep Beauty has only been an object, separate from the world she existed in. Her awakening means her transfer from the realm of the passive to the active. “The story of ‘The Sleeping Beauty’ is a perfect parable of sexual trauma and awakening” writes Angela Carter (from “the Better to Eat you With”, 1976). In Perrault’s version, which Carter was referring to, Beauty has scarcely awakened before she is hastily married, and then retires to a different bed altogether; the marriage bed (“After supper, the chaplain married them in the castle and the chief lady-in-waiting drew the curtains round their bed for them”, from Archive Source 2). Depending on translation, this fact is either emphasised or swept under the rug; my translation by Christopher Betts reads; “They slept little, for the Princess had very little need of it”, when in the original French text it reads; “They had but very little sleep— the Princess had no occasion.”. Carter in her 1977 translation turns it into “They did not sleep much, that night; the princess did not feel in the least drowsy.”

Perrault explicitly follows his “the Sleeping Beauty in the Wood” up with the moral that girls should better be patient to wed, and “lovers lose nothing if they wait, / and tie the knot of marriage late”, though he also remarks that with young girls’ known impatience for marriage, he cannot find it in his heart to seriously preach this moral. Marriage is actually one of the main concerns of a lot of fairytales, as we have seen before. Popular fairytales like “Bluebeard” and “Beauty and the Beast” were both meant as cautionary and instructional tales for girls to navigate the world of marriage, and the unfamiliar men they might encounter in their suitors and eventual husbands. “Fairytales written during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries were intended to teach girls and young women how to become domesticated, respectable, and attractive to a marriage partner and to teach boys and girls appropriate gendered values and attitudes” (from Archive Source 1)

II.III Sleepwalking Through Life

“Some people fake their deaths. I'm faking my life.”

quote from “Sleeping Beauty” (2011)

Many have taken it upon themselves to draw out the erotic undertones of the Sleeping Beauty narrative, for it is only a short jump from unconsciousness and objectification to submission. Anne Rice recognised this when she used Sleeping Beauty as the main character for her erotic saga “the Claiming of Sleeping Beauty” (1983), which quickly abandons fairytale tropes to lead into straight-up BDSM writing, its Beauty learning the “power” of sexual submission after it is forced on her; “[…] and there was in her, even in her helplessness, a sense of power.” Despite this potential for eroticism, Sleeping Beauty has more commonly become a sort of anti-feminist figurehead representing the woman as complacent, devoid of agency, sleepwalking through life. In the 2011 film “Sleeping Beauty”, which is based on Yasunari Kawabata’s “the House of the Sleeping Beauties” (1961, more on that later), main character Lucy is living a life of passivity, moving through her daily routines like an automaton, devoid of both pleasure and pain.

“If her suffering itself becomes a kind of mastery, it is a masochistic mastery over herself.” // “Her life is dominated by chance”

by Angela Carter, writing about the Marquis de Sade’s “Justine” in “the Sadeian Woman and the Ideology of Pornography” (1978)

This is why some strain to be submissive instead of just complacent; the sensations submission bring are self-validating, and can even be empowering. “Is it that sometimes the pain inside has to come to the surface, and when you see evidence of the pain inside, you finally know you are really here?” asks James Spader’s character to Maggie Gyllenhaal’s- a burgeoning submissive- in the 2002 film “Secretary”. Regardless of the structures of patriarchal, phallocentric society that oversee them, active choices are always better than passivity, even if the difference is only small.

The point is also that women’s submissiveness as a self-realising tool vs. as depicted in most pornography is that the former is a pursuit for women’s pleasure, centred in the one being submissive (it is an experience lived), and the latter is mostly promoting female submission as a tool for male pleasure, with seemingly no stock put into whether the woman is enjoying it. It’s Schrödinger’s “submissive” woman; she might be enjoying it, she might not, but the limits of the pornographer’s format offer us little to no way to discern reality from fantasy. There is no amount of observation that could break the spell, could help us distinguish which is which. Pornography as a medium facilitates no “breaking of character” that might reassure us about the falsehoods of distress2.

Unfortunately, our choices do not exist in a vacuum. The question of what is empowering to oneself, on a larger scale, has to at least brush over the question of what is societally empowering. Anne Rice’s Beauty makes no choice in her submission: it is thrust upon her, and therefore, not something that liberates her from anything at all. Baselessly assuming submission because of gender is not a “choice” at all. Whether we like it or not, ideas of [gendered] power dynamics are intrinsic to sexual ones. Louise J. Kaplan asserts this in her book “Female Perversions: the Temptation of Emma Bovary” (1991), stating that [sexual] “perversions” are inextricably linked to social constraints and gendered stereotypes. One such “perversion” she notes for women is one of extreme submission, based on extrapolated stereotypes of women as “pure”, “fragile”, and in need of protection from their desires. This condescending notion is a doubling of an internalised place of assumed inferiority.

The question of submissiveness is simply doomed to be eternally complicated, for there are no scissors sharp enough to free us from the strings of societal norms and expectations. It’s impossible for us to imagine a world wherein [feminine] submission might be a choice wholly devoid of these strings, for we have never seen a world completely lacking these gender stereotypes; even as we move to undo them, their traces run deep. Perhaps if we cannot untangle ourselves, we can at least ensure that all of our choices are deliberate. Not baseless, not automatic, not made out of complacency, but as choices made with real soul. Attempting to be an active advocate for our own pleasure, always. No matter how hard it is.

Looking beyond sexual submission, can simple placidity ever be empowering? One could argue that the unnamed protagonist from Ottessa Moshfegh’s “My Year of Rest and Relaxation” (2018) is a sort of modern day Sleeping Beauty or a foil to the earlier Lucy: stereotypically beautiful (white, skinny) but undoubtedly weighed down by her own sense of ennui and boredom— so much so, that she chooses to medically induce a year of pretty much uninterrupted sleep in herself. But of course, life continues all the same even as she sleeps, and her unconsciousness does little to remedy her fatal boredom. It just helped kill the time.

Despite the legions of young women who claimed the novel’s protagonist as a sort of flagship-figure for their quarter life crisis, Moshfegh’s novel is a condemnation of passivity in excess. Sleep, and by extension passivity, is only restorative when used wisely. Lucy from “Sleeping Beauty” (2011) gets entangled in a sort of mock brothel where older men pay to sleep next to beautiful, young (naked) girls, chemically ensured not to wake up. The house forbids its clients from doing anything unsavoury to the girls, but that is not the violation most important to the business model. Lucy’s microdosing of a drug-induced deathlike sleep is “restorative” as her employer tells her, but only because the enigma and curiosity of those lost hours stirs her to action. In the second to last scene, Lucy is resuscitated, having been given an overdose of the sleeping medication, only to find the man next to her has died. All at once, the horror of the unknown morphs into the horror of the known— lesser, but much more effective. Lucy screams and sobs as if being re-born. The final scene of the film shows a flashback from only a few hours earlier into the night; the old man, presumably already dead, and young Lucy, fast asleep, peacefully in bed with one another.

II.IV The Fairest of Them All

“Discourse analyses reveal several several themes in relationship to beauty. Often there is a clear link between beauty and goodness, most often in reference to younger women, and between ugliness and evil (31 percent of all stories [analyzed in this study] associate beauty with goodness, and 17 percent associate ugliness with evil.”

from Archive Source 1

“Sleeping Beauty” (2011) was based on a short story entitled “House of the Sleeping Beauties” (1961), by Yasunari Kawabata. The broad strokes of the plot are largely the same, but follow one of the clients instead. As the protagonist of the story, Eguchi, finds himself returning to the “House of the Sleeping Beauties” he reflects on his own relationships with women, his dwindling youth, and his sexual history. The girls here, are a conduit for the flow of youth, with their “maidenly hair”, “scent of milk”, and “softness of sleep”; “For the old man, she could be life itself”. The selling point of the house itself is hope: the hope, however foolish, of somehow transferring a bit of youth from the girl to the man— the opposite of what seemingly happened in the film adaptation. For Eguchi, the taboo and the silent sordidness of the whole subdued affair seems like an injection of excitement: the paramour of youth is often vigour. “And around the old men, new flesh, young flesh, beautiful flesh was forever being born. Was not the longing of the sad old men for the unfinished dream the secret of this house?”

In one of his nights spent at the House, Eguchi remembers a woman he met when he was younger, who confessed to him that whenever she was unable to sleep, she would recall a list of men she wouldn’t mind being kissed by, implying Eguchi to be among them. The confession, made in nonchalant earnestness, unsettles him, as he feels almost defiled and stained by the notion of “being enjoyed” in someone else’s mind. It is a small taste of the objectification he then mirrors onto the sleeping girls as he wonders about their bodies and whether they’ve had lovers, not noticing his own projection of that defilement he loathed when cast upon himself. Unable to see himself as the object of someone’s desires rather than the fully participating subject, or even the one doing the desiring, he radiates desire like a sinful, intruding shadow onto the unwitting flesh next to him in the night. This is a gendered parable: to be a man is to desire, to be a woman is to be desired. Any undermining of this duality is unnatural to the rigid gender norms of Eguchi’s mind and lived experience.

Beauty, like youth, is currency, let’s not kid ourselves. You are far too enchanting to play the fool, my dear. One needs only read these fairytales to find its significant focus on descriptions of beauty, especially the beauty of its female characters. The genre itself exhibits a sort of scopophilia, or a pleasure in looking. Fairytales, through their minimal use of dialogue and focus on descriptive, all-knowing narrators, tend to take a great pleasure in looking at its characters. The women especially exist to be looked at. No female character escapes the narrative’s all-seeing gaze, labelling them as “fair” and “golden-haired”, or “ugly” and therefore evil. In my readings of Perrault, Andersen, and Grimm for this letter, I had to abandon the idea of marking them all down, as they were simply too plentiful. We would be stuck here for days.

Male characters get largely the same treatment, but with a few caveats; they might be dashing, but they will also be remarked upon as brave or courageous or fierce. The study from Archive Source 1 found that while men’s beauty is not necessarily related to how often a fairytale gets reproduced through the decades, any reproductions that did get made put a greater emphasis on male beauty as well as female beauty, though not in parallel quantities— the mentions of female beauty went up exponentially compared to mentions of male beauty. But despite the oppressive beauty standards within the tales, their male characters are still more likely to get access to a wider variety of plot lines. Both “Cinderella” and “Snow White”, the most reproduced fairytales, give their female main characters plots that are largely facilitated and driven by their beauty first and foremost. Their antagonists, too, are primarily driven by beauty and by female competition over beauty. There is always someone younger, prettier, more innocent lined up to take their place. And so, women continually cannibalise each other’s virtues within fairytales. Look how easily they bow to cruelty.

“The feminine beauty ideal can be seen as a normative means of social control whereby social control is accomplished through the internalization of values and norms that serve to restrict.”

from Archive Source 1

II.V Dominating the Narrative

“She has the mysterious solitude of ambiguous states; she hovers in a no-man’s land between life and death, sleeping and waking.”

by Angela Carter, from “the Lady of the House of Love” (collected in “the Bloody Chamber”, 1971)

It’s interesting to note that in her fairytale retellings Angela Carter chooses not to tackle “Sleeping Beauty” outright. While the other tales play much more obvious games with their source material, “the Lady of the House of Love” is barely recognisable as a Sleeping Beauty adaptation, and it’s a stretch to me to even call it that. Carter chooses to shape both Beauty and her Prince here into the male protagonist; a virginal soldier off to war. He is both victim and saviour, of himself and of his counterpart, the vampiric, young, and beautiful Countess. She is the one most aptly described as “asleep”; an immortal and eternal virgin, eager to break her “curse” of virginity but instead continually succumbing to her bloodlust and killing her suitors. Equal parts femme fatale and childlike-ignorance.

Carter’s retelling makes much more sense when we, ourselves, try to imagine a feminist retelling of Sleeping Beauty. It’s hard to imagine Beauty, a mostly passive princess, as a liberated figure. Women’s [sexual] submission in general, is rarely able to successfully present itself as freeing, especially as long as submissiveness is the “expected” or “default” state of women in the bedroom. Somewhere, somehow, in my research I picked up the phrase “the [sexually] submissive woman is last to be liberated”3. I have no clue where it came from, or who to attribute it to, but it stuck around nonetheless.

The other side of the D/S coin- the dominant woman- has amassed much more cultural capital than the submissive woman has. Why is that? Movements like the 90s’ “Riot Grrrl” movement and its punk origins used the transgressive aesthetics of BDSM to reject “nice girl” feminism, depicting women as filled with rage, “hysterical”, slutty, in charge, and ultimately dangerous to male power. The point was to upset the status quo. But the dominatrix is also a male fantasy; what Louise J. Kaplan calls the “phallic” woman; a woman who takes on the attributes of the male fetishist becomes, herself, a fetish. Kaplan even goes so far as to write; “In truth this phallic woman, who has been assigned the role of a powerful and dominating humiliator, is a demeaned woman, a prostitute, a Playboy bunny, a wife or girlfriend who submits, unwillingly or willingly, to the perverse script of the man who directs the performance and pay the bills.” (p24).

The performance of the dominatrix is still easily reclaimed as a feminist, empowering experience by being a choice, a pleasure for she who partakes in it, rather than something forced onto unwilling wives and hesitant girlfriends. But arguably, the sexually dominant woman is ultimately not very disruptive to ideas of male power as long as the men participating in the fantasy can reconfigure the dynamic to actually be for their pleasure. Whoever claims the pleasure holds the power. This is also what Angela Carter sees in the Marquis de Sade’s writing: “To be the object of desire is to be defined in the passive case. To exist in the passive cases to die in the passive case – that is, to be killed” (from “the Sadeian Woman and the Ideology of Pornography”, 1978). And yet dominance, rather than submission, is much easier to reclaim for feminist purposes because BDSM imagery like the “dominatrix” and related iconography is certainly a more permissive visual shorthand for female power than their active submission is. The image of kneeling is, when removing context of the willing woman, just an image of submission to male power. It’s hard for it to be seen as anything else.

Recently, the film “babygirl” (2024) made a splash for its depiction of a woman with clear societal power as a choice submissive. Main character Romy is a CEO, arguably an artefact of so-called “girlboss feminism”, but she is sexually unfulfilled because she habitually denies her own wish for a more submissive and masochistic role in the bedroom. Throughout the film, as she learns to voice these wishes through an affair, she has to continually unpack not only her own shame, but also eventually her husband’s confusion about her desires, who in his frustration tries to undermine Romy’s feelings by telling her that “Female masochism is a male fantasy, a male construct, don't you fucking get that?”. Director Halina Reijn, for her part, has said that the film is a “warning” about what happens when we don’t acknowledge and learn to accept all parts of ourselves.

The aforementioned “Secretary” (2002) makes a point to show us that the protagonist Lee’s submissiveness and masochism is, indeed, something she herself seeks out and yearns for. Beyond her initial tentative explorations of it, which come as a surprise to her, but offer her plenty of room to step away, she continues to seek out her own [sexual] punishment as a playful, tongue-in-cheek, active participant in it. “babygirl” too, takes this approach, focusing on agency as well as the messier, imperfect parts of this alignment. Reviews calling its vision "delightfully un-feminist” are missing the point; it is not that sex and sexual dynamics do not need to be feminist. It’s that female submission, when properly explored, is actually feminist. Feminism, after all, is all about bodily autonomy and female agency! The image of the damsel in distress might fool you, but as Dita von Teese, Nina Hartley, and Liz Goldwyn joked in a panel session: “she claims to be a damsel in distress, but she’s actually built the railroad tracks, tied herself to them, organised the lighting, and has the train on cue!”4

Perhaps, with a wider in-depth cultural discussion about submission, Sleeping Beauty is next to be reclaimed? A girl can dream, after all. Whether she does so once, or for a hundred years, well that depends entirely on the narrative— one she always has the potential to rewrite.

III. Museum Recap: February

“We go all the way to the altar, to the butcher's, we can't help ourselves, we go all the way to where we don't want to go, it's irresistible. Pushed by desire and terror mixed. […] One must almost die in order to take pleasure in being made flesh, we've always known this. What time is it? Time to be eaten. Passion.”

by Hélène Cisoux, from “What is it o'clock? or The door (we never enter)” (Collected in “Stigmata: Escaping Texts”, 1998)

From time to time, I like to take the space here in my letters to reflect on some of my recent happenings, from events, to museums, to travels. Today is an instant of the middle. This letter can be a journal, if I want it to, my dear. If you’ve been keeping your lovely eyes open, you might have noticed the new “On the list” section at the end of my recent letters, which is meant to be directory for all things happening soon. That’s for the present, the future. These recap sections are uniquely concerned with the past. Feel free to retrace my footsteps, if you like.

Having explicitly and plentifully dabbled in Freud for last month’s letter on psycho-analysis, dreams, and sleepwalking, it was only a matter of time before I went to check out the Freud museum— and oh, am I glad I went. The museum is small, but packs a powerful punch, mostly through its completely preserved study, featuring that one very iconic couch, and a strong smell of old books and carpet. Truly, I had trouble ripping myself away from that room, just examining all the hundreds of little details. At one point the home movies playing upstairs showed a print of Henry Fuseli’s painting “the Nightmare” (1781) in the waiting room, which is, unfortunately, no longer there. The short “Women & Freud: Patients, Pioneers, Artists” exhibition also featured a great deal of familiar names, from Louise Bourgeois to Princess Marie Bonaparte, which I eagerly enjoyed.

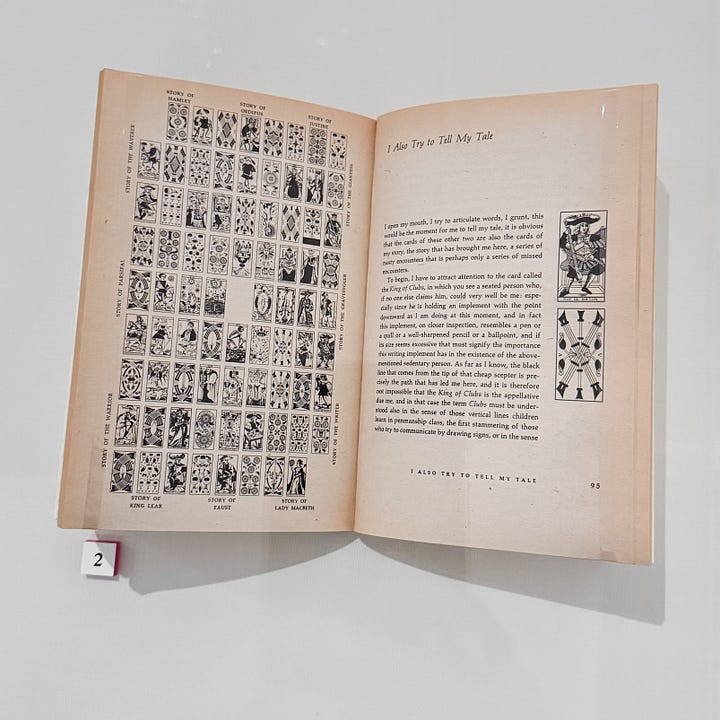

Additionally, the new exhibition “Tarot: Origins & Afterlives” opened at the Warburg Institute this month, so I gleefully went to check it out with some most lovely companions in tow. It’s a relatively compact exhibition, very doable in size, but with a wealth of artworks that you could, theoretically, spend a great deal of time with. It was my very first time at the Warburg Institute, but it certainly won’t be my last. Afterwards, we spent about five more hours just browsing the various witchy and occult bookshops in Bloomsbury, like my beloved Atlantis Bookshop, and the Astrology shop nearby. A great day for all my esoteric, occultist interests!

Finally, if there is one lesson I would like to (humbly) convey to you this month, it’s that whenever there is some event or shindig upcoming that you are interested in, to book immediately. Yours truly learnt this the hard way, being met with an unending line of “sold out” for the “Medieval Women” exhibition at the British Library. Truly and completely my own fault, of course. But it does suck that even my best skills of seduction couldn’t get me inside. Take it from me; do not be a Sleeping Beauty. The beauty part they could, of course, never take from you, my dear. But it is the sleeping part that concerns me. Awake into action and you won’t feel like such a fool as I did, standing outside the British Library, unsuccessful in my attempts. Better to be awake and prevent such a fate.

There is no rest for the wicked, anyway.

✧・゚: *✧・゚:* On the List *:・゚✧*:・゚

Exhibitions, events, and talks. In the spirit of active participation, there are two exhibitions both ending in a few months, that you might want to check out before their due date. These are “the World of Tim Burton” at the Design Museum (ending May 26th), and “Tarot: Origins and Afterlives” at the Warburg Institute (ends April 30th). Additionally, “Women & Freud: Patients, Pioneers, Artists” is on at the Freud Museum until May 5th.

Museum events that might be of interest to you include “Marie-Antoinette: Not Just a Pretty Face” at the Wallace Collection, a free online talk taking place on the 12th of March. Meanwhile, the National Gallery has picked our beloved “the Execution of Lady Jane Grey” by Paul Delaroche to be their painting of the month, so short free talks about the painting are available in the museum on the 5th, 12th, 19th, and 26th of March.

Now, if you’ll allow me to be a bit indulgent, the most exciting event of all is of course Ethereal Maison’s upcoming “Rose Croix Rituals” event on the 7th of March, which promises to be a night invigorating performance night of rituals and reclamation, including some poetry performed by yours truly! If you come, don’t be too shy to say hi! ☆

Completely unrelated, but Tumblr’s favourite holiday of misfortune and doom, the Ides of March, is on the 15th. Maybe hide the knives for the day and avoid large gatherings of friends. It’s for the better, trust me.

Film, Music, and TV. If you also impatiently keep up with Holly Black’s Elfhame books, then rejoice, for you can finally complete your paperback collection with the second half of the “Stolen Heir” duology, “the Prisoner’s Throne” (2024), finally releasing in paperback on March 6th at Waterstones. Additionally, the new Hunger Games book “Sunrise on the Reaping” is due for release on March 18th.

In other news, Season 3 of “Yellowjackets” (2021-) is currently premiering on Paramount+, with episode 5-10 all dropping throughout March. Additionally, my favourite video game “Bloodborne” (2015) turns ten on the 24th! Surely this means they’ll announce a sequel, right… right?!

At the BFI, the re-release of “Picnic at Hanging Rock” (1975) is well underway with screenings taking place until and including the 13th of March. Gothic lovers can also rejoice because the iconic haunted house film “the Innocents” (1961) is available to watch on March 9th at the BFI as well.

In the Stars. The spring equinox is coming up on the 20th of March, marking the beginning of spring [in the Northern Hemisphere], so get your candles and flowers out to welcome the warmer weather and the awakening of all things that bloom. Additionally, there’s a full moon on the 18th, also known as the Worm Moon, prompting the question; would you still love me if I was a worm moon?

Obsessive Tendencies: What I’ve Loved Lately

ASOS, bow monogram tights in “black”, [Accidentally ripping these on Valentine’s Day felt worse than getting my heart broken], on sale for £7

Disturbia, Menagerie textured button up blouse top, [The sweetest top to be angelically evil in], £38

Charles Perrault, the Complete fairytales of Charles Perrault, [My favourite out of the three fairytale authors I read this month], £10.99

Rituals, the Alchemy body cream, [Luxurious cream, richly scented of mysterious amber and warm myrrh— delightful!], £25

Freud Museum, dreaming “pills”, [A lovely little bedside decoration, that is also thematically apt!], £4.90

the Inkey List, glycolic acid exfoliating body stick, [With warmer weather coming on, it’s time to prepare your skin by gently using a chemical exfoliant, like this stick], £15

“There isn't anything in this world but mad love. Not in this world. No tame love, calm love, mild love, no so-so love. And, of course, no reasonable love. Also there are a hundred paths through the world that are easier than loving. But, who wants easier? We dream of love, we moon about, thinking of Romeo and Juliet, or Tristan, or the lost queen rushing away over the Irish sea, all doom and splendor.”

by Mary Oliver, from “March” (collected in “White Pine”, 1994)

My dear, there is a “happy ever after” looming in the distance, darkening out the evenings and bringing forth the sun. Here, from the comfort of my own Blackberry Hill House, it seems I could simply beckon the spring to close in on us all, plant a daffodil in the craters of the moon, let the crocuses sing. Oh, what a short and hectic month it’s been. March, for me, promises to be interesting too; I’m going to Paris, performing some of my poetry, and I’ll have to get around to posting all these fairytale-themed submissions. Alright, my dear, my clock is chiming now, so it’s time for me to take my leave. Please remember: if there is simply too little saviours, with too many damsels to go around, it is always the wise choice to awaken, and save yourself.

Until my next letter,

With love (and violence),

x Sabrina Angelina, the White Lily Society

Currently reading: “I, Julian” by Claire Gilbert // Most recent read: “Hans Andersen’s Fairy Tales” by Hans Andersen

White Lily Society links // Sabrina Angelina links

And they lived happily ever after. Oh, wait… Maybe I spoke too soon. To get the good ending, I would wisely recommend subscribing to the White Lily Society, my dear. It’s free, and very good for the soul. Come, join us, and become a martyr of deliciousness.

Full 2000 page motif index available on the Internet Archive

I am aware that some modern pornography videos do have pre- and post-scene interviews with their participants (mainly the women), in which they can discuss their excitement, enjoyment, and experience. More of that, please!

Update: it might’ve come from “babygirl” (2024)!

super interesting and well researched read !! I absolutely love your voice as a writer 💗

Love your words ✍🏼✨