29. Monstrous Vows

Remember; cleanliness invokes the stain.

“Icy mirrors, fiery roses, ambiguous grace. December arrives, bleeding and cruel.”

by Georges Rodenbach, from “Clouds of Light, in a Diamond Mist,” (1880)

If you are enjoying the White Lily Society’s writing, curation, or other activities, please do consider making a small donation— it not only supports me as your de facto cult leader, but also helps keep the society free and accessible for all. Thank you endlessly <3

01/12/2025, London, UK

My dear,

December is a frightful beast. It is time to wrap everything up again. Gifts (in paper), the world (in snow), the self (in layers). The final act of another foggy year. November was a call to embrace pyromaniac tendencies, but December is for settling among the ashes. The scent of burnt firewood clings to frosted roots. Frozen ground and its paws grabbing you by the ankles. Best keep all beloved extremities close to you, lest they turn blue with winter melancholy. Frost is all-consuming, my dear, so let it peel the woollen remnants of yourself away. Perhaps they would make a lovely gift for the madmen or madwomen in your life…

Or do as filmmaker John Waters advices; “I always give books. And I always ask for books. I think you should reward people sexually for getting you books. Don’t send a thank-you note, repay them with sexual activity. If the book is rare or by your favorite author or one you didn’t know about, reward them with the most perverted sex act you can think of. Otherwise, you can just make out.” (the New York Times, 2013)— pretty straight-forward, no verbose gift guide required. Arguably better than letting the ravens or the crows or the robins whisper their strange songs to you. Birds always end up suggesting a self-sacrifice, a nose-dive into the fire. Returning to the self as thing to be stripped away and passed down, like some twisted heirloom.

Though I pointedly didn’t love the new “Frankenstein” (2025) as much as I wanted to, I’d be lying if I said it hasn’t been on my mind. Incessantly so, even. In truth, the third act sent me down a rabbit hole of veils, of vows, of virtue marred. Wondering if the bride is ever allowed to live… Which led me here. To this altar, staring you down across the aisle. Start the choir now, I am ready!

And I do take you, my dear, to be my lawfully wedded darling, to have and to hold, from this day forward, for better, for worse, for richer, for poorer, in sickness and in health, until death do us part…

‧₊˚🖇️ ✮⋆˙ ₊˚💌⊹⋆。𖦹 ° This newsletter contains the following sections:

I. Archive Sources // II. Bridal Gothic: looking at the wedding of Death and the Maiden // III. One Battle, Après un Autre: Battle & Paris travel updates // “On the List” December, Current Obsessions // Outro (w/ affirmations for the end of the year)

I. Archive Sources

“Desire doubled is love and love doubled is madness.”

by Anne Carson, from “the Beauty of the Husband” (2001)

In lieu of another vow, my dear, I wish to profess my undying devotion through the act of curation. As always, it is no good to rush through the ceremony. Therefore, I have taken the time to fill this here proverbial cathedral with sources for you to gush and gawk over, in preparation for the main event. Allow me to gather you up something old, something new, something borrowed, and something blue.

“The Bride and Her Afterlife: Female Frankenstein Monsters on Page and Screen” - link

A discussion of the 1935 “Bride of Frankenstein” film (and its cultural impact), which notably marketed itself on the mystery of what the Creature’s monstrous bride would look like, and not what she would do, or say, this paper notes. This literal unveiling is relevant to the bridal theme, but also objectifies the idea of the female monster as spectacle to look at. Second best, she has done away with much of the novelty of suspense (Will Victor succeed in creating his perfect man?), instead focusing on secondary characteristics, such as looks. Mary Shelley’s 1818 novel treated the female monster as unfinished body, described as something to be worked on, dreaded, and then discarded. Cast off into her separate parts, and then the ocean, she is a stain of a question mark haunting our cultural fascination long since the novel’s release.

“She also problematizes cultural assumptions about what should be considered “monstrous” and what, in turn, “beautiful.” […] Whale’s Bride is striking and alluring in her white dress and towering hairdo, yet she hisses, grunts, and screams in as subhuman a manner as her betrothed. Although her initial appearance signals grace, her movements are jerky and halting like those of a marionette or automaton; while she lacks the metal bolts of her male counterpart, she is clearly post-human. She is seductive and there is an iconic, resonant quality to her beauty, yet her scars are ever-present reminders that she is a put-together thing.”

“‘Ideology and Sexuality among Victorian Women” - link

Instead of comparative analysis taken from literature, this paper presents a brief statistical study of Victorian women’s attitudes towards sex and sexuality from a period data set known as the “Mosher” data. It’s an enlightening, quick read, that gets into some of the numerical nitty-gritty of the question, and gives a good overview of data to pair with literature for a balanced review. After all, it never hurts to check your facts, my dear.

“[…] many Victorian-era women viewed sexual relations as important within marriage, but a large number also failed to perceive a basic human need for frequent sexual intercourse. The prevailing view within Victorian society seemed to be that couples, particularly women, simply did not need more than a minimal amount of coitus, or could, alternatively, divert themselves to other activities yielding greater social and material rewards.”

“Gothic Repetition: Husbands, Horrors, and Things That Go Bump in the Night” - link

This paper discusses “marital Gothic” and the evil husband trope, pinpointing these down to the heroine’s very legitimate realisation of horror that her patriarchal education did not prepare her accurately for its dependants; marital abuse, misogyny, violence, control, and the brute-force perpetuation of feminine1 helplessness. The prescribed cure within the story is not an escape from this pattern, but the repetition of it. Repeating the same scenario but hoping for a different outcome, the very definition of madness. Rather than recognising the false bargain of marriage, the textual repetition claims that the heroine, silly girl, has picked the wrong husband! Once she marries a worthy husband, she is expected to disappear into the wifely ideal without any such friction, having repaired the status quo without frivolities such as emancipation or self-actualisation.

“[…] discussion of a particular variant that I call “marital Gothic,” a later form of the genre where the husband is present at the beginning rather than the end of the story and “repeats” the role of the father. The trope of the husband allows us to consider how and why the figure who was supposed to lay horror to rest has himself become the avatar of horror who strips voice, movement, property, and identity itself from the heroine.”

II. Bridal Gothic

“My place was never in this world, I sought and longed for something I could not quite name. But in you, I found it. To be lost and to be found— that is the lifespan of love.”

from “Frankenstein” (2025)

Bridal Gothic is everywhere, once you know how to look. It’s been haunting me, sneaking up on me in my sleep, a spectral visitor in my home, ever since I watched the Creature carry Elizabeth’s limp body, bridal style, in “Frankenstein” (2025). It seemed a veil had been lifted. Past work gained new dimensions. Rewatching “Bram Stoker’s Dracula” (1992), I couldn’t help but note bride-related lines: “You’re the bride my master covets” Renfield tells Mina through the bars of his confinement. Fragments from “Nosferatu” (2024) recited from memory, re-appearing as if summoned; “[Count Orlok] cares only for his pretty bride”.

Death and the Maiden did not seem to be done with me yet, my dear. Its crumpled wedding invitations, splattered with blood and scented of lilies, appeared on my doorstep en masse. My mind became an altar to its intricacies. I witnessed their union over and over again, I memorised their vows. The spirit of the wedding bed stayed with me as I poured over their ancient texts… Though the sanity of my results is not guaranteed. You have been warned, my dear.

II.I Bridal Symbolism Unveiled

“Open my legs, lie down with Death / We kiss, we sigh, we sweat / His blackberry mouth stains my nightgown / I pull him close, wrap my legs around / And it tastes like life”

by Florence and the Machine, from the song “Witch Dance” (2025)— capitalisation on “Death” my own

Starting our slow descent into madness, we must first examine the scene of the crime. There are a multitude of superstitions and symbols associated with the [Christian] wedding, especially the bride, and thus with bridal Gothic. Starting with the veil. The word itself carries a multitude of associations; people speak of the “veil” between life and death, to “unveil” means to reveal, veils are understood to be thin, gauze-like, tantalisingly transparent. The veil represents both the means both to cover up, as well as to reserve the possibility for uncovering. There’s a duality there, friction between intent and inevitable action— we will run into these multitudes again and again.

Like the white lily, which is traditionally both a wedding flower and a funeral flower, the “Death and the Maiden” trope represents a union, a cross-section, a blending of both love and death; two eternal principles meeting. The Intersection of Love and Violence. Furthermore, the colour white, which is often associated with the bridal figure, with weddings, represents purity, innocence, and virtue. But outside of the Western world of semiotics, white can also be associated with death and mourning. It follows the same principle as the veil; cleanliness invokes the stain. The absence of one thing only accentuates it, not erases it. Duality is rooted within the very symbols of bridal Gothic.

“Elizabeth is so covered up and she’s got all these layers on her. And as she’s getting closer and closer to the Creature, layers of her clothing start to be removed, and it’s as though she’s been hiding all of this time.”

by Mia Goth, from a Netflix interview clip, on Elizabeth meeting the Creature in “Frankenstein” (2025)

In Guillermo del Toro’s “Frankenstein” (2025); veils are an oft-utilised motif. When the Creature first meets Elizabeth, she lifts up her veil to be closer to him. As a character, she is often veiled, hidden away from the world, withdrawn perhaps as a reference to her origins in a convent (an unreleased scene in said convent also shows her, wearing white, with a matching veil). All this bridal symbolism persists into her death later in the film. Del Toro has effectively rewritten the character from Mary Shelley’s original novel to have a more inquisitive, active impact on the story. His Elizabeth Harlander (not Lavenza) matches Victor’s scientific curiosity. She gets her hands proverbially dirty, whether that’s in catching butterflies or in her tender, maternal investigation of the Creature. Nevertheless, both Shelley’s and del Toro’s Elizabeth are not allowed to live to the end of the narrative. The bride must die, one way or another: the marriage unfulfilled only adds to its tragedy.

This tragedy is reinforced by superstition. Because of the tangle of del Toro’s rewrites, the iconic wedding night from the book gets reworked into a wedding day. Instead of Elizabeth’s wedding to Victor, it is now her wedding to his brother William (aged up in the film). But all this change does not save her. When Victor visits Elizabeth at her vanity as she gets ready, he remarks that it’s “bad luck to see the bride before the wedding”— an oft reinforced wedding superstition. Elizabeth responds, slightly annoyed, “Only for the groom”. Not much later in this third act of the film, exactly that happens; not William but the Creature lays eyes on this woman in white, and disaster strikes immediately. In the ongoing chaos, Victor, aiming for the Creature, fatally shoots Elizabeth. Superstition blossoms.

Del Toro explicitly describes this (and the following) scene(s) as a wedding between Elizabeth and the Creature. Carried bridal style, down the steps and through the crowd, as the two seclude themselves in their tragedy. Elizabeth’s dress, with its bandaged design, is meant to evoke the titular “Bride of Frankenstein” from the 1935 film. A character whose absence is imprinted onto the text, both in the original novel as in del Toro’s adaptation. Or at least, absent in the shape of a female Creature purpose-built. It turns out, one does not need to start from scratch to find connection, woman is already capable of empathising with the Other2. “There is a beautiful marriage of souls in the film. […] The creature gets a bride and loses her on the same day.” (Del Toro, again) This is their twisted wedding; the Creature in his furs, the blood spreading through Elizabeth’s white dress. The Maiden consumed by death, the Maiden in Death’s arms.

II.II Marrying a Widow / Bridal Utilitarianism

“Adapting a book is like marrying a widow. You have to respect the late husband, but on Saturdays, you are allowed to get it on.”

by Guillermo del Toro, on adapting “Frankenstein” (1818), in conversation with Forbes (2025)

Marrying a widow is the right metaphor, alright. It perfectly reflects the adaptational attitude towards the bride, oft shuffled around and assigned different meanings based on context, authorial intent, mood. Symbolically fluid, ephemeral, shimmering. Hard to pin down. Elizabeth’s death, while true to Mary Shelley’s novel as a plot point, has very different connotations in its original form, where her murder is conducive to the Creature’s revenge against Victor. There, the Maiden’s succumbing to Death is not reflective of the Maiden as desirable or as transformative, empathetic power, but as property. Shelley’s creature kills Victor’s loved ones, including Elizabeth, to directly harm his creator, to condemn him to the same eternal loneliness. This is the difference between the bride-as-property and the the-bride-as-beloved (!).

“I heard a shrill and dreadful scream. […] She was there, lifeless and inanimate, thrown across the bed, her head hanging down, and her pale and distorted features half covered by her hair. Every where I turn I see the same figure— [Elizabeth’s] bloodless arms and relaxed form flung by the murderer on its bridal bier.”

by Mary Shelley, from “Frankenstein” (1818), p199, (bolded words my own)

This same identity split is quite pronounced in “Dracula” (1897) and its myriad of adaptations. Whether the cycle of violence against its bride(s) is enabled in the name of love or in the name of property differs per interpretation. When Stoker first penned the tale, the friction in the novel resided much more clearly between Johnathan and the Count. When the Count goes after Mina, Johnathan’s wife, he does so in the spirit of weakening her husband, of threading despair in the group hunting him through the streets of London. It is not necessarily a personal affront. The Count’s assault on Johnathan in the castle, and later against Mina, is an assault on Johnathan’s masculinity and its dependants: his ability to defend himself, to master his own lust, to protect what is “his”. Mina is only a means to an end. The violence perpetrated against her is strategic, my dear. When the Count force-feeds her his blood, the passage’s cruelty reinforces the bride-as-property, while its imagery alludes to the bridal;

“With his left hand, [the Count] held both Mrs Harker’s hands, keeping them away with her arms at full tension; his right hand gripped her by the back of the neck, forcing her face down on his bosom. Her white nightdress was smeared with blood, and a thin stream trickled down the man’s bare breast which was shown by his thorn-open dress. The attitude of the two had a terrible resemblance to a child forcing a kitten’s nose into a saucer of milk to compel it to drink.”

by Bram Stoker, from “Dracula” (1897), p300 (bolded words my own)

In Francis Ford Coppola’s 1992 film adaptation of the story, “Bram Stoker’s Dracula”, the dice are recast to invent a love story between the Count and Mina. The scene of violence in the bedroom (see quote above) becomes much more tender, willing, consenting— the lovers mean to spent eternity together. Their encounter resembles wedding vows, complete with mentions of death and eternity. At first, the Count hesitates; “I cannot let this be. […] You will be cursed as I am to walk in the shadow of death… for all eternity. I love you too much to condemn you”, to which Mina replies, ironically, “Then take me away from all this death”, and Dracula finally gives in. The visual motifs remain the same as before; white nightdress, blood on the sheets, the hushed air.

While Mina here takes on the role of bride-as-beloved, Coppola’s iteration of Lucy still gets the bride-as-property treatment. Drained for the sake of it, and buried in white. Mina, on the other hand, serves as love interest, as main focus of the Count’s motivations, not because of her connection to a man, but in spite of it. Her status as soon-to-be-wife is actually an inhibiting factor to their relationship, as she is torn between her attraction to the Count, and her wholesome love for Johnathan. On the ship on her way to marry, Mina muses: “And now, without [the Count], soon to be a bride, I am lost”. She is reluctant to leave behind the intriguing Count, to marry the steady object of her affections, Johnathan.

This split between one who is passionate, but frightening, and one so virtuous, if a bit dull, is a classic device of early romance fiction, before it started merging the two male leads into one (see Jan Cohn, “Romance and the Erotics of Property”, 1988). And this triangle formation between “monster”, “hero”, and “the girl”, has a seemingly endless library of related tropes attached3…

II.III The Graphs! They’re Alive!!!

“No great mind has ever existed without a touch of madness.”

by Aristotle

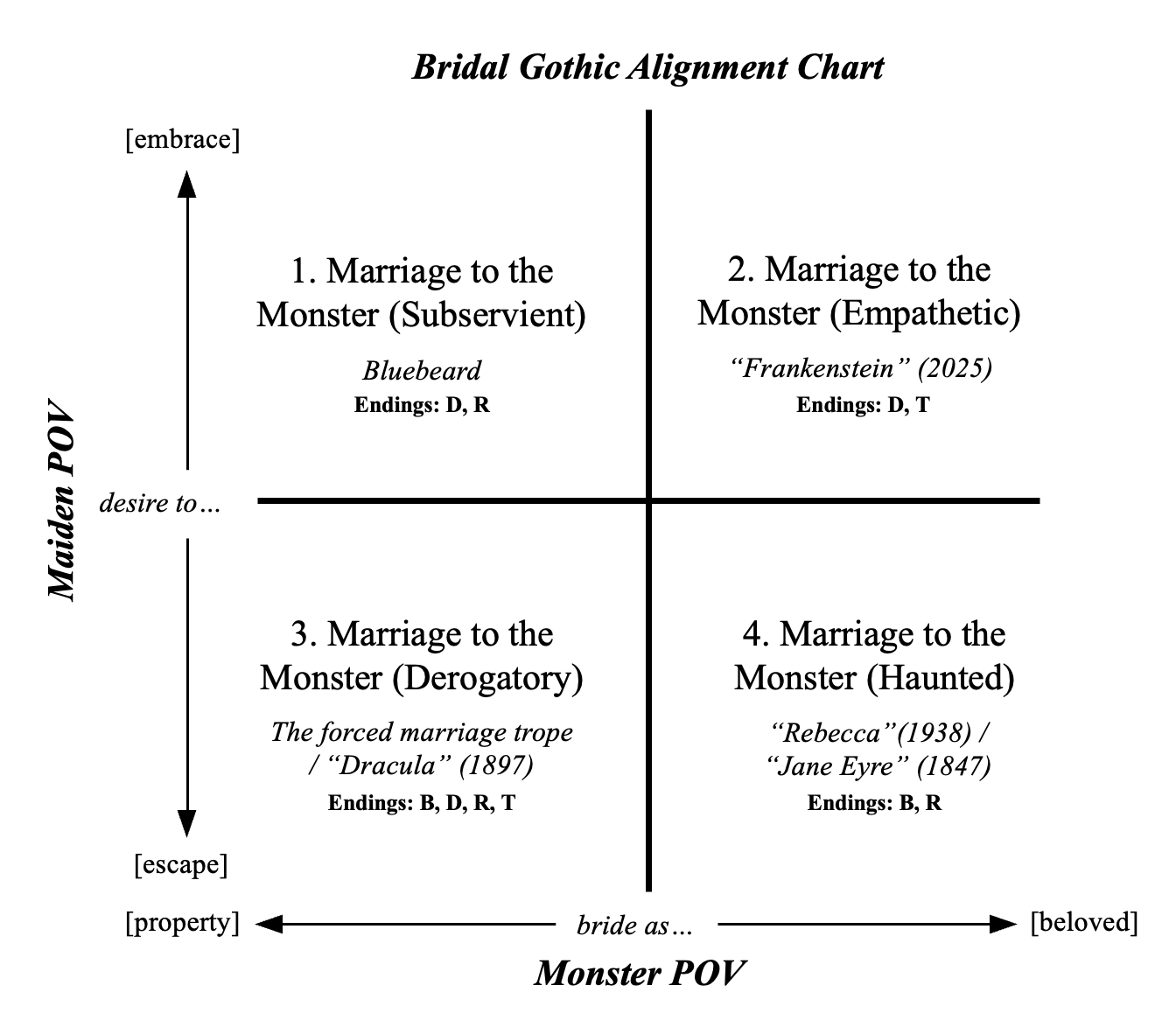

This is where I might lose you to my all-consuming madness, my dear. By this point, I realised that our examples so far have proven that bridal Gothic does not live or die by one trope in specific, but I was starting to narrow things down. I had a conspiracy board and everything. So I did what any sane, rational person would do, and spent three hours making a chart separating what I believe to be the four main bridal Gothic tale types4— based on the previously established split between bride-as-property, and bride-as-beloved (taken from the monster’s POV), as well as either the desire to escape or embrace the monster (from the Maiden’s POV).

The resulting four types of bridal Gothic are: (1) Subservient, (2) Empathetic, (3) Derogatory, and (4) Haunted (See chart below). Some of these, like type 4, are more likely to be the “human strain” of DatM, in which the “monstrous” bridegroom is not physically or externally monstrous, but rather monstrous in character. Others, like type 2, are almost entirely of the literal Monster strain, which speaks for itself. It’s the difference between merely representing death, and being Death himself.

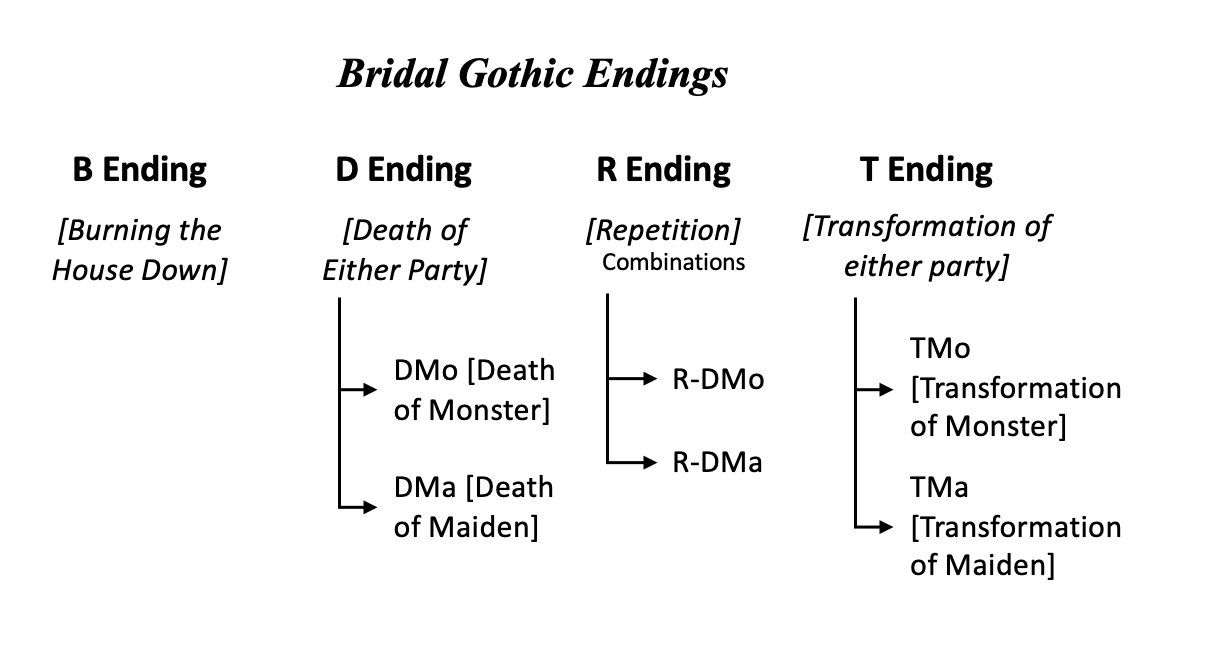

But one chart wasn’t enough, no. As I started thinking of these tale types, my mind naturally wandered to the endings associated with them. After another hour or two, I boiled these down to a theory of the four most common root endings (with further branch / combination endings pictured in the second graph below);

[3, 4] Burning the House Down: where the Maiden’s flight response is triggered by external circumstances rather than the Monster (read: husband) himself, these are resolved or removed from the equation, ie. the house burning down (“Jane Eyre” 1847, “Rebecca” 1938).

[2, 3] Death of either party: the Maiden consumed by death (DMa, a classic case of dead bride syndrome) (“Frankenstein” 2025, “Nosferatu” 2024), or the Monster perishes instead (DMo, “Bram Stoker’s Dracula” 1992).

[1, 3, 4] Repetition5: the Maiden survives and re-marries a less monstrous husband, but doesn’t escape the confines of marriage completely (Bluebeard)— both “Dracula” (1897) and “Bram Stoker’s Dracula” (1992) are arguably an R/D combination6, specifically R-DMo.

[2, 4] Transformation of either party: the Monster is tamed (Hades and Persephone) or transformed (TMo, Beauty and the Beast), or the Maiden turns monstrous (TMa, “the Shape of Water” 2017, Angela Carter’s “the Tiger’s Wife” 1979).

II.IV Until Death Do Us Part

“Patriarchy … is at home at home.”

by Joan Kelly, taken from “Romance and the Erotics of Property: Mass-Market Fiction for Women” (1988) by Jan Cohn, p73

Marriage, both in the real world and as a plot device, is often a simple brick road leading to the home, and to filling that home with children, as was (and largely still is) the heteronormative ideal. But marriage to the Monster (Death) does not often lead to a home, or a house to call one’s own. Neither does it lead to offspring. In this way, the marriage between Death and the Maiden is a perversion of the typical “order” of marriage, supplanting it instead with the “chaos” of emotional, rather than physical, belonging. For example, though Guillermo del Toro’s “the Shape of Water” (2017) does not contain an explicit marriage, Elisa’s new gills at the end of the film do imply a renewed symbolic belonging and enmeshment. A long-term commitment. The ocean is her home with the “Amphibian Man” (as his character is credited) now. But the depths of water are not so much a place, as they are an idea, an emotion. Literal submergence. There is no building a home against the current that is always moving.

Perhaps one could say that the DatM marriage then, paradoxically, rejects the fundamentals of marriage. At least in part. There is still the idea of prolonged, if not infinite, attachment to one another; death as a life-state is quite permanent, after all, my dear. But the DatM marriage often does not lead to, or doesn’t make it to the ideal of “settling down”. In Dutch this is referred to as “huisje, boompje, beestje”: a descriptor of a calm, domestic life involving (literally) a house, garden, and a pet. Americans might summarise this ideal in the white-picket fence, the clear boundary of where the home (safety, domesticity) ends and the world (uncertainty, chaos) threatens to invade.

But this boundary between hearth and hazard is not nearly as impenetrable in the DatM romance. The Gothic novel is famous for having manors besieged by invaders (“We Have Always Lived in the Castle” 1962, “the Castle of Otranto” 1764, arguably the final act of “Dracula” 1897), or for having them burn down (“Jane Eyre” 1847, “Rebecca” 1938). Even in Disney’s 1991 saccharine-sweet “Beauty and the Beast” adaptation the castle is swarmed by a mob of armed villagers. The home isn’t safe and the marriage is doomed to end in flames or death, or both. Monstrous as it may seem, the DatM marriage is devoid of the guileless assumption of [physical] safety. Though love in death is eternal, loving Death is the ultimate vulnerability. There is no place to hide.

This vulnerability is anxiety-inducing, especially in relation to the event of the wedding as a threshold of sorts. Ellen has nightmares about a wedding with Death, foreshadowing Count Orlok’s arrival in “Nosferatu” (2024). In anticipation of her marriage to the vampire Edward, Bella dreams of a monstrous wedding gone wrong in “Breaking Dawn Part 1” (2011), where, interestingly, everybody is wearing white, so the red blood soaking through is even more striking as a visual. Remember; cleanliness invokes the stain. That’s not to say that this anxiety is misplaced. Very rarely do bride and groom, Death and Maiden, cross over into that unfamiliar, strange “happy ever after”. One, or both parties, must die, if not the wedding averted altogether. The rare few times that it does work out are the exception, not the rule. Hades and Persephone might have established the archetype, but their marital bliss is certainly not typical for their imitators.

II.V Death of the Self

“Marital Gothic begins with, or shortly after, a marriage— the same marriage that provided a sacramental expulsion of horror […]. Perfect love supposedly has cast out fear, and perfect trust in another has led to the omission of anxiety discussed above as an antecedent of repetition compulsion. Yet horror returns in the new home of the couple, conjured up by renewed denial of the heroine’s identity and autonomy. The marriage that she thought would give her voice (because she would be listened to), movement (because her status would be that of an adult), and not just a room of her own but a house, proves to have none of these attributes. The husband who was originally defined by his opposition to the unjust father figure slowly merges with that figure. The heroine again finds herself mute, paralyzed, enclosed, […]”

via Archive Source 3

But not all monstrous husbands are physically so. Let us not forget about the parts of bridal Gothic in which the husband is not literally a Monster or a beast, is not a capitalised, personified Death, but rather represents death and violence symbolically. This “strain” of bridal Gothic brings with it its own set of fears and anxieties. The marriage, here, is frightening not only because of the threat of masculine violence, but because of the identity entrapment associated with it. This fear of marriage as mistake, as gilded cage, or even as foreboding premonition stems from the social climate in which this genre was at its most popular. The late eighteen and early nineteenth century, when forced marriage Gothic was arguably at its peak, had little to no security for women, and virtually no opportunities for them to make their own way in the world. Divorce was uncommon, if not impossible. To be a bride meant to belong to the husband, as legal property. Arranged marriages gave birth to the Bluebeard archetype; the monster in the wedding suit. Unmasking only after the vows are binding.

There was simply little to no margin for error in one’s pick of a husband. Even if one mostly manages to avert tragedy, the heart is still a fragile thing. In “Jane Eyre” (1847), the halted marriage of Jane and Rochester is, on paper, a good thing. Exchanging rings would have meant Jane’s forced silence about Rochester’s first wife, the madwoman in the attic, her footsteps audible through the creaking wood above the marriage bed. If, post-nuptials, the truth ever came out that his first wife was not dead but mad, the scandal would be all-consuming, starting with devouring any sense of [financial] stability and [legal] protection Jane could hope for.

But Jane’s heart has already walked down the aisle, and agony is inevitable; “The house cleared, I shut myself in, fastened the bolt that none might intrude, and proceeded - not to weep, not to mourn, I was yet too calm for that, but - mechanically to take off the wedding dress and replace it by the stuff gown I had worn yesterday, as I thought, for the last time.” (by Charlotte Brontë, 1847) Even in doing the right thing, the aborted wedding causes anxieties. The imminent death of the self, and expected rebirth, snatched so viciously from Jane’s measured hands is crushing. “Jane Eyre, who had been an ardent, expectant woman — almost a bride, was a cold, solitary girl again: her life was pale; her prospects were desolate.”

Marital anxiety does portent to doom in bridal Gothic. Both death and the wedding vows are a symbolic handing of the self to the Other; unification with the unknown. Like the bride has historically belonged to her husband, to die is to be consumed completely. The phrase of “taking” a wife, as is common in Christian wedding vows, is almost a Persephone reference. No pomegranate seeds needed. The secrecy of the whole ordeal only makes it more frightening, the hushed refrains of marriage little girls endure in childhood. Illicit references to an elusive husband yet unknown. “You’ll know when you’re married”, “That’s between a husband and wife”, “One day you’ll have a husband of your own”.

Suppose that marriage is a kind of Hades, a dark underworld glittering with treasures known only to the married couple. A closed door to a bedroom is almost a River Lethe. Who knows what goes on beyond? And why wouldn’t you be frightened? The wife disappears from the places, the life she inhabited as a bride. And this fact does not go unnoticed. Emily Dickinson, for example, uses the exact same language to write of her friends’ marriages, as she does of their deaths. “When people get carried off to marriage, they are not heard from again; they procrastinate with their former friends, no longer making time for connecting. Marriage, understood as a matter of time, carries women off.” (by Marianne Noble, from “the Cambridge Companion to Erotic Literature”, 2017).

According to Lacan, the woman “does not exist”. Or rather, she exists both within and partially beyond the symbolic order. Certain facets of her exceed the phallocentric structure of identity and meaning. She cannot be categorised as something, nor as the absence of something. The highest extension of this is the bride; the woman not yet bound by vows. In between girlhood and its patriarchal ideal of a purpose; motherhood (which in its own way, is a kind of disappearance, a non-existence). In the original “Frankenstein” (1818), Victor has a nightmare of his beloved Elizabeth, first touched by death, and then morphing into the corpse of his mother, rapidly shedding and re-aligning new states of self;

“I thought I saw Elizabeth, in the bloom of health, walking in the streets of Ingolstadt. Delighted and surprised, I embraced her; but as I imprinted the first kiss on her lips, they became livid with the hue of death; her features appeared to change, and I thought that I held the corpse of my dead mother in my arms; a shroud enveloped her form, and I saw the grave-worms crawling in the folds of the flannel.”

by Mary Shelley, from “Frankenstein” (1818)

The shroud here is akin to a veil. The bride is the ultimate state of limbo, not belonging to the self, nor the father, nor the eventual husband; “the danger and fascination that the bride exerts can also be attributed to the fact that she could potentially belong to everybody, that she could be anything and everything” (by Elisabeth Bronfen, from “Over Her Dead Body: Death, Femininity and the Aesthetic”, 1992, p270). But when that husband is Death, the Other, she once more escapes categorisation into the Void of Semiotics. What can belong to Death, when its corresponding state is one the dissolution all ties? Who owns that which does not exist? Which does the rot belong to; the body or the forest floor, both or neither?

II.VI the Sexually Active Wife

“[…] voices a passionate yearning for jouissance, for shattering of the constraints of identity, for an ecstatic merge with with totality, for orgasm. Subordination to a husband may not be an earnest wish for [Emily] Dickinson, but an erotic sublime – an ecstatic surrender to an orgasmic, overwhelming flooding of sexual sensation – might well be.”

by Marianne Noble, from “the Cambridge Companion to Erotic Literature” (2017), p163

There is a third, and final anxiety, or even an eagerness, we have yet to discuss. Like the others, it is dual-sided, sharp like a knife. Where is the line between husband-as-liberation and husband-as-entrapment? Nestled into sin, death by a thousand paper cuts. At first, picking a husband represents a shimmering infinity. The beauty of the husband is the choice between sham liberty in the arms of one man, or another. Girls grow up eager for it, frustratingly reaching for chances to grasp onto the privileges of womanhood. An expansion of their limited freedoms. New identities to try on.

Marriage was (and in some cultures, still is) the only virtuous, acceptable outlet for sexuality… to an extent. Rather, sexuality was sanctioned, by church and society, only so much as to serve procreation, not pleasure, and only taking place between a married man and woman. Feminine sexuality, if it was even acknowledged, existed purely in a reactionary state, through a spiritual bond with the husband… Or so the literature of the time states. It’s hard to estimate if these attitudes were similarly reciprocated by the general population, though. Most of these texts, whether denying feminine sexuality, or dramatising masculine sexuality, could be read as fetish texts in themselves, my dear. Katie Hickman, in her work “Courtesans: Money, Sex and Fame in the Nineteenth Century” (2003), posits that a not insignificant portion of such morality texts could have been written for fetishistic gratification, rather than to accurately reflect Victorian society. Vigilance is required.

What little data we have on Victorian sex lives within marriage, like the Mosher survey (see Archive Source 2), seems to suggest that Victorian women’s reported sexual pleasure had little effect on the frequency of sex in their marriage, both actual and ideal. That does not, however, mean that these women did not harbour sexual desires. Rather, the vicious repression enforced on them largely forced these desires into other channels, like the novel. Reading is a pleasure, after all, my dear. The romance and the Gothic novel each fulfils different feminine fantasies; the former revolves around the ideal of the heroine succeeding within the structure of patriarchy, while the latter is more concerned with the pleasures, thrills, and the “strange luxury of artificial terror” (by E.J. Clery, from “the Rise of Supernatural Fiction 1762-1800”, 1995) the supernatural can provide. Ideals normally smothered for women under patriarchy.

The romance novel trope of the sexually potent villain, forcing some poor heroine into marriage, then, is really just an excuse for secondary eroticism to be imprinted onto the [consenting] reader, through the conduit of the non-consenting or hesitant heroine. Contrasting the moustache-twirling villain to the vampire anti-hero, the crux of their difference is the heroine’s (Maiden’s) attitude towards him: desire to escape / desire to embrace (!). The monstrous husband is what happens when masculine sexuality is weaponised against the heroine, while the Monster husband represents the more enticing (yet still dangerous) facets of it. Gothic, as a genre that often wields the language and motifs of horror, equates sex with death, but also maintains the allure of this duality, both in spite, and because of it. And so the plot thickens..

Monstrous bridegrooms, more frightening than alluring at first, softened over time as our cultural understanding of them expanded. Jan Cohn, in his book “Romance and the Erotics of Property: Mass-Market Fiction for Women” (1988) alleges that, as social norms eased, the romance hero and villain characters gradually morphed into one. Now, the monstrous husband could exemplify both the heroine’s safe space, as well as the force pushing her out of her comfort zone. Refined, seductive, but also dangerous, animalistic, [sexually] aggressive. The dualities of Rochester rather than the single face of Bluebeard.

The personified Death, too, became understood as a force both tender and terrifying, capable of romance. “Because I could not stop for Death / He kindly stopped for me” (by Emily Dickinson, 1890). The Monster became an sympathetic creature: modern audiences are much more likely to respond to the subtext of the relationship between Monster and Maiden (see; the amount people rooting for #TeamOrlok in response to “Nosferatu”, 2024), and their stories are more often set up that way too (see; Guillermo del Toro’s re-writes for “Frankenstein”, 2025). When these tales originated, the thought of the Monster as anything but malicious threat was hardly considered within the text. The Count in Bram Stoker’s original “Dracula” (1897) represented a fear of the Other, a fear of the sexual seducer “stealing one’s girl” in the sense of an assault on property, not a consensual seduction.

Bridal Gothic, especially the monstrous husband trope, is the natural conclusion of [feminine] marital anxieties about entrapment, the loss of self, and repressed sexuality. A fiction in which these fears are legitimate beyond the inexpressible confines of patriarchy, the murky lines we can feel but not name. “No, you are not on the brink of madness.” bridal Gothic whispers. Something really is wrong, my dear. Beyond the yellow wallpaper, this house is a trap, and your husband has the keys. He has the choice of being your jailor or your liberator, and he might not even know it. How could you ask of him, what you cannot put into words?

The ultimate, final freedom is always within death, is found in loving Death. The sexual allure and appeal of the Monster (Death), is something I have written about extensively before— but it all boils down to this: love is masochism. We give our lovers a unique power over us: the power to [emotionally] hurt and maim us like no other. All these fears of marriage, of monstrous husbands, of dying to ourself, and so on, exist in one turbulent maelstrom. The dominant Romantic ideal is one of tragedy and passion, intertwined; the Intersection of Love and Violence. The Monster simply makes these abstract notions explicit. “The horror was for love. The things we do for love like this are ugly, mad, full of sweat and regret. This love burns you and maims you and twists you inside out. It is a monstrous love and it makes monsters of us all.” (from “Crimson Peak”, 2016). So let us be monsters, then, together, and embrace the things that frighten us at night. Both literally, and figuratively.

III. One Battle, Après un Autre

“You are today, Madame, the renown, the preoccupation, the scandal and the toast of Paris. Everywhere they talk only of you…”

by Alfred Delvau, from “Les Plaisirs de Paris” (1867), about the courtesan Cora Pearl

☆ As always, my current film setup of choice is a Canon Sure Shot 85 Zoom, paired with Kodak ColorPlus film. For those gloriously blurry digicam pics, I use a Sony Cybershot DSC-WX80 (the 16.2mp variant) ☆

My November, my dear, was quite a journey of flame and flight— thank you for asking. I spent a cold few days in Battle in a cottage from 1433 with barely any heating, but with great company to make up for it. We spent the weekend trailing the Battle of Hastings and exploring the Gothic remains of the abbey, rummaging through charity stores, and sitting by the fire. Eager for warmth in the rickety hallways of the home. A pyromaniac theme emerged; on Saturday evening a procession of torches to celebrate bonfire night, culminating in fireworks and an inferno as tall as the abbey nearby. Smoke stained our clothes and could be smelled for days more. I also had the immense [dis]pleasure of losing grandiosely at a game of Trivial Pursuit (in my defence, this was a version from before I was even born)— which is how I learnt that Percy Shelley was expelled from Eton for stabbing. The more you know!

Not a week later, I found myself carrying my luggage over Parisian cobblestones, welcomed by the most exquisitely vivid orange sunset. I felt immediately at home again. Paris can have that dizzying effect on you, you know. All the glimpses of eras long gone will sweep you right off your feet. Anyway, I spent the first few days with my beloved friend, arriving late on Friday and going out for dinner, caught off guard by the Arc de Triomphe and gawking at the sparkling majesty of the Eiffel Tower. Tourist sights I’ve often ignorantly ignored in favour of more esoteric fare. What can I say, I’m a bit of a snob on occasion.

On Saturday, we went on a walking tour of Montmartre in the morning, hearing about artists, and suicides, and tragic romances. All the lovely things. Stopping by the lovely “Saint Jean de Montmartre” church to light a candle, and the statue of Dalida, on our climb up to the “Sacré-Cœur” cathedral. Plenty to digest, for all this yearning is hungry work! Best to enjoy a crêpe on the way down, then. Just to be sensible. Then, after a long day, I had my first ever oyster (very salty), paired with three glasses of an overly sweet dessert wine while we got ready for a very, very, very special occasion. A real dream came true…

Yours truly had evening tickets to “le Crazy Horse”, a classic topless revue that’s been going since 1951. Scandalous and champagne-fuelled, the Crazy Horse has seen a multitude of stars and starlets grace its infamously shallow stage: Dita von Teese was their first ever guest star in 2006, an experiment she repeated two more times in Paris, and four more times at MGM’s “Crazy Horse Paris” show in Las Vegas. But the wall of celebrity visitors inside is seemingly never-ending— you can spot any manner of celebutante or personage, from Elvis Presley and Man Ray, to Alfred Hitchcock, Madonna, and David Lynch. Now that’s a list of names I would be in good company in.

The show is made up of a great selection of short, song-length acts, involving protection mapping, planed mirrors, lighting effects, conveyor belts, and, of course, a few poles here and there. The act of stripping itself is markedly absent, so what you see, is what you get. The vast majority of the show’s iconic acts are still here: “God Save Our Bareskin” and “But I’m a Good Girl” remain untouched (pun intended), while my favourite “Teasing” has been partially reworked into “Voodoo”. We had “restricted view” tickets, which were great. These slightly discounted tickets place you on the side of the room, but you won’t feel like you’re fully missing out on more than one out of a dozen acts. Sometimes, dancers on the side are not visible, but when they are all doing the same or very similar choreography, it doesn’t take away from the effect at all. It’s still an entirely spellbinding night, my dear.

Consequently, the late night (or early morning?) meant an even later rising on Sunday, and a long walk along the Seine to reflect on our debauchery. We took a short stop at the world’s most charmingly underwhelming cannon ball lodged in the side of a building on the “Rue du Figuier”, before crossing the river to drink some earl grey and play a few games of chess at the atmospheric “Blitz Society”. One Parisian bistro and one more Eiffel Tower sighting later, I settled into my hotel room for the next few days.

As a little side-note, my previous favourite gluten free bakery in Paris has been indefinitely dethroned! In the game of pastries, you either win, or you get unceremoniously replaced in a later newsletter… This entire trip, I spent fueled by pastries from “Copains” (which, serendipitously, has also appeared in Covent Garden in London)— croissants, cinnamon buns, and warming apple turnovers, I just couldn’t resist! Nor am I enough of a masochist to deny some Dionysian revelry… When life gives you pastries, you don’t suddenly become a bakery prude. Declining gifts is rude, my dear. When in Paris, you simply can’t shun a fresh croissant.

That first day on my own, Monday, mere hours after resigning to solitude, I went and visited my favourite church in Paris, the “Église Saint-Eustache”, taking a lengthy moment to inhale its Gothic splendour. Straight medicine for the soul. On my way to the métro afterwards, a gaggle of French youths yelled something in my direction, with a tone I could only describe as… wholesome excitement? My French is far from fluent, my dear, so all I could make out were the words “porcelain” (“porcelaine”) and “doll” (“poupée”)… I was headed to “Montparnasse Cemetery”, dressed in my best goth finery. A lolita coat (It has bows! It has lace! It flares out like a skirt!), paired with mary janes, frilly gloves, a brown lace skirt, and a newfound love for sheer white foundation. Of course I took it as a compliment. What else is one to do?

It was quite cold out, but I was warmed by a lengthy promenade through the cemetery, visiting Baudelaire’s lipstick-stained grave and seeing the dizzying array of tombs in the morning gloom. Over-estimating the steadiness of my own feet, I trailed through the 6th arrondissement, buying a gorgeous pendant at a religious store named “Georges Thrillers”, visiting the “Église Saint Joseph des Carmes”, and browsing the edible fineries of “La Grande Épicerie de Paris”. For dinner, I nestled in at my favourite spot, “Le Procope”, for a classic French bistro experience in a historic setting. You know the restaurant is good when it has its own Wikipedia page, my dear. The narrative importance adds extra flavour.

On the second day, a hasty hotel check-out and a Copains croissant for the road, as I was determined to see the “Gabrielle Hébert: Amour fou à la Villa Médicis” exhibition (on until February 15th) at the “Musee D’Orsay” before my departure later that day. There are few things that can coax me into rising early, but a good exhibition is certainly one of them. This one combined so many of my paramours: a story of devotion, romanticism, and early 19th century photography. There is something about the look of a gelatine print or silver albumen positive that has such a spectral, otherworldly quality about it. It’s a very dreamy medium. Enchanted by the exhibition and with my time dwindling rapidly, I had the quickest dip into the larger museum to see Gustave Courbet’s infamous painting “L’Origine du Monde” (“Origin of the World”), before hurrying along to grab lunch and catch my train home, returning to dreary London once more, from where I write to you now. Au revoir, Paris! We will meet again!

✧・゚: *✧・゚:* On the List *:・゚✧*:・゚

[My recommendation: use this month as medicine to ease yourself into the new year. Spend time with family, friends, or arch-nemeses, if you like. The White Lily Society event calendar will return in January <3]

Obsessive Tendencies: What I’ve Loved Lately

Dark in Love, “Dreda” Lace top, [Black lace is an everyday essential, my dear], £55

Made by Mitchell, Build Foundation in “LB1”, [The perfect sheer white foundation for that porcelain doll look, as validated by Parisian youths], £20

FromSoftware, “Dark Souls 3” for PS4, [A gorgeous gift for my fellow masochistic gamers], £44.99

Dark in Love, “Cecilia” skirt, [Wearing miniskirts in the winter may not be my smartest aspiration, but certainly very cute], £42

Punk Rave, “Whispers” blouse in white, [A goth can never have enough white blouses!!!], £69

Dark in Love, “Circe” black gloves, [Aesthetically sensible mittens for the winter], £23

“In the winter I am writing about, there was much darkness. Darkness of nature, darkness of event, darkness of the spirit. The sprawling darkness of not knowing. We speak of the light of reason. I would speak here of the darkness of the world, and the light of……. But I don’t know what to call it. Maybe hope. Maybe faith, […].

Faith, as I imagine it, is tensile, and cool, and has no need of words. Hope, I know, is a fighter and a screamer.”

by Mary Oliver, from “Winter Hours” (collected in “Upstream: Selected Essays”, 2016)

And so that leaves us at the end of the year, the precipice to a foreign land. We cannot know what the other side holds for us, at least, not more than a preview. I know my January will be one of cardboard boxes, of burlesque glamour, of re-reinvention. All my carefully laid plans will slowly start blossoming, from the new bedframe I picked, to surviving the desolate winter, now with a tree in front of my window. My current ambition for my move in February is to get an elaborate Victorian dollhouse and absolutely dote on it with Gothic miniatures and ardent adoration. I want to deck my second coming of Blackberry Hill House in lace curtains and dark wood. As is to be expected.

This will be my first time celebrating the winter holidays in London, enjoying the last months in this nest of mine, trying not to succumb to fruitless melancholy. What is frightening can only sneak up on us once we turn our back on it, remember that, my dear. The monster under your bed wishes you well, and so do I. Do not forget that in the loneliness of the month’s festivities. For what it’s worth, I almost lost my left thumb in a bread-knife related incident while writing this newsletter. Talk about being committed to the Intersection of Love and Violence… Real blood, sweat, and tears, are tucked away in this envelope.

Affirmations for the end of the year (repeat after me)

It is okay that my problems are largely insignificant in the eyes of the greater universe, and that I yet still feel them very deeply

I am not in need of a cure

The possibility of surviving the winter without total hibernation is greater than the possibility of succumbing to the cold

Until next year,

With love (and violence),

x Sabrina Angelina, the White Lily Society 𐔌՞. .՞𐦯

Currently reading: “Dracula” by Bram Stoker (yes, still) // Most recent read: “Doves and Pomegranates” by Christina Rossetti

White Lily Society links // Sabrina Angelina links

See anything you like? Why not make a vow eternal, and pledge your fealty? No ring nor honeymoon guaranteed… Come, join us, and become a martyr of deliciousness.

📼 Song of the (past) month: Buckle - Florence and the Machine

My continued use of “feminine” / “masculine” as descriptive terms rather than “female” / “male” is an effort to recognise the learned gender norms and their associations, and through less enforcing language, open up the conversation to possible queer or non-binary perspectives. Violence, for example, is not inherently “male”, but rather gets taught to those AMAB as a “masculine” construct, the same way helplessness or domesticity are taught as “feminine” to those AFAB.

See also, my works "13. Death and the Maiden II" and "25. Death and the Maiden III" for more in-depth analysis of this aspect.

I do also want to add that all of these tropes have their non-heteronormative counterparts and supplements. Think for example of the “bury your gays” trope, which is made of similar matter to the “women in refrigerators” trope. Though my work on DatM tends to skew quite heteronormative, there is lots of potential for queer text adaptations, which I have mentioned before, such as “Killing Eve” (2018-2022), “Hannibal” (2013-2015), and “Interview with the Vampire” (show 2022-, or book from 1976).

Almost all bridal Gothic is DatM, but not all DatM is bridal Gothic. I’m sure there’s exceptions to any and all parts of this insane theory I’m weaving here, but my head hurts— trying to categorise “Nosferatu” (2024) for example, could be either a Type 3 “Marriage to the Monster: Derogatory” or Type 4 “Marriage to the Monster: Haunted”, though the ending is most definitely an DMa (see footnote below).

Adapted from Archive Source 3.

“Wuthering Heights” (1847) is an outlier because our main protagonist is not the Maiden (Cathy), which enables it to be an R-DMa “ending” (in relation to the main Heathcliff/Cathy relationship).

I adore your bridal gothic alignment chart and for fun, have been attempting to label a few other media within its organisation. My first thought was seeing if it could apply to queer relationships, and I found it did for Carmilla!

Also, I too went to Paris recntly and saw the Crazy Horse and can agree it's such a spectacle to watch what countless other notable persons have seen. Also I agree the restricted seats weren't bad at all!

Brillaint taxonomy of bridal Gothic endings. The four-quadrant framework (property vs beloved, escape vs embrace) cuts straight to the structural tension that makes these narratives so compulsive. Especially insightful how transformation and repetition endings functoin as mirrored escapes from teh marriage trap itself.