13. Death and the Maiden II

A full thesis-length deconstruction of my favourite trope

“Wind and storm coloured July.”

by Virginia Woolf, from “the Waves” (1931)

01/08/2024, London, UK

My dear,

With the ebb and flow of rising darkness, comes a bright light to meet it. While shadows gather, you and I sit at candlelight in my mind, locked in fierce discussion as always. Perhaps there is a rose on the table, perhaps it’s a lily (white, of course). Imagine there is the smell of loveliness in the air. What form does tenderness take?

If it is rot you are after, look no further. The mold is within the fruit, laying dormant, waiting for an invisible countdown to end. The same way death curls up into our chest, waiting to unfold itself in due time. The same way Death himself stalks through the night, looking for souls to reap. Anaïs Nin, my patron saint this July, said that she harboured within her a passion for truth, and one for darkness. I suppose I feel mostly the same.

I spent a taste of my dreary and dream-like July in Yorkshire, the bulk of it at home, pondering, and then a good chunk of it contemplating the theme of this month’s newsletter, namely “Death and the Maiden”. Yes, again. I have touched upon it very briefly before, but surely you didn't think I could resist the call any longer? It is, of course, the anniversary date for this newsletter’s existence, and that means this one is salaciously and scandalously and sanctimoniously long. Consider it my gift to you, extra juicy at no extra cost.

But before we begin, ask about new things, and ye shall receive! Oh, these are marvellous, untouched things. Look as they sparkle and shine! All of the past month was dedicated to posting “Death and the Maiden” content, a little sampler for what this newsletter is about to serve you in full glory! There were write-ups, one in which we compare two interpretations of nightmares, one about Victorian mourning practices, and about Henry Fuseli’s painting “the Nightmare”, as well as plenty of other artworks and videos depicting the trope in action. Unrelated, there is also a short write-up about Alexander McQueen’s AW06 show “the Widows of Culloden”. Now, that’s a quality amuse-bouche.

Let us move on, let us move on! We have so very much to dive into. A venerable rabbit hole awaits, a full buffet, and I have spared not word nor thought in delivering it all to you.

I. Archive Updates

“I love you like a rotten dog, / I love you like my canines are falling out of my gums, / Like a monster, like a beast / Like something not worth loving back”

by Tory Adkisson, from “Anecdote of the Pig” (2021)

I’ve always threatened that I could write a full-length thesis on “Death and the Maiden”, and now (surprise!) I finally made good on those threats of mine. They are empty no more! You are holding the result right here in your hands. The average bachelor thesis, I’m told, is about eight thousand to fifteen thousand words long. For my own masters degree in strategic fashion management, I wrote sixteen thousand words. This newsletter is roughly twelve thousand words long. Make of that what you will.

But, of course, this gargantuan thesis of a letter would not be complete without sources, and oh, how we love our academic sources! Here, let me show you what I’ve curated for your viewing pleasure today.

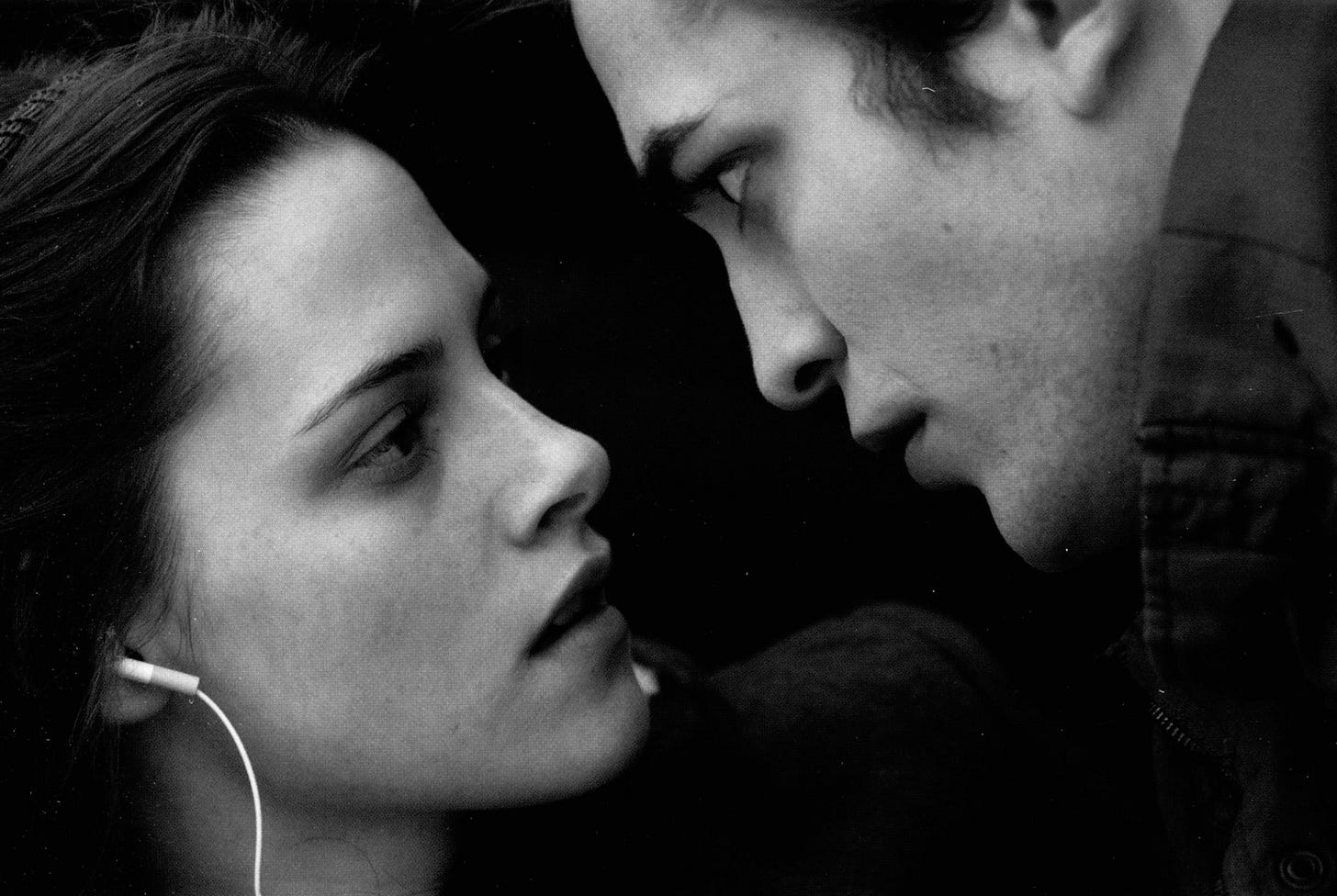

“(Un)safe Sex: Romancing the Vampire” - link

Starting off with a guaranteed hit, this paper looks at a few modern adaptations of modern vampire romance media to ponder why cult classics like “Twilight” have so steadfastly captivated their respective [mainly female] audiences. Of course, it’s through centring female viewpoints and female desires. Another interesting facet of trivia this compact paper points out is that Bella, throughout both the book and the movie, is defined by her scent, not her looks. Edward’s first impression of Bella is her scent, which is constantly remarked on, and even tracker James identifies Bella as human on the baseball field only when the wind carries her smell. I found that to be quite intriguing. Throw in a clever “Bella and the Beast” pun and some “Wuthering Heights” (1847) references, and yeah, you’ve got me.

“But the complex qualities of the hero– his mix of sense and sensibility – is not the only reason women seem to have such an insatiable appetite for vampires today; another attraction may be the point of view these texts adopt. They are female–centered narratives that strive for audience identification with the heroine— with her strengths, her extraordinary capabilities, her status as an object of desire, or a combination of all these traits. She is the focus of the story […].”

“From captivity to bestiality: feminist subversion of fairytale female characters in Angela Carter’s “the Tiger’s Bride”” - link

Touching on hypertextuality and gender norms in fairytales, this paper discusses Angela Carter’s subversive feminist retelling of “Beauty and the Beast”— one of my favourite short stories of all time. Spoiler alert, but in the series of dazzling alterations she makes, the largest one is in fact that the traditional ending is reversed, and Beauty willingly turns into a beast at the end. In her story, Carter’s Beauty showcases an extreme willingness to detach from social and gender norms, and in becoming like her Beast, she successfully manages to undo the years of wily suppression that have plagued her life. It’s something you just have to read, and then afterwards, return to this paper for a lovely bit of analysis as the final cherry on top.

“Beauty’s metamorphosis takes place and she also becomes a beast. In this way, Carter wants to underline the equality between the genders as well as to dismiss the meaningless influence of the patriarchal society which instructs men to be dominant, cold and reserved while requiring women to be modest, patient, obedient and subordinate. Moreover, Carter subverts the traditional flow of fairy tales where the prince is freed from the animal body in order to live as a human. She transforms her heroine into a beast and by doing so, the author celebrates variety, individuality, freedom of choice and otherness.”

“Gentleman Death in Silk and Lace: Death and the Maiden in Vampire Literature and Film” - link

Considering that this final source is, in fact, a whole entire thesis like mine, I would like to point your attention first and foremost to Chapter 1, which presents a very good groundwork of references for the “Death and the Maiden” trope in vampire literature and media. The paper then goes on to look at “Dracula”, both the novel and Francis Ford Coppola’s 1992 film adaptation, as well as “Interview with the Vampire” (1976) and it’s 1994 translation to the big screen. Though perhaps a bit lengthy, it is a very thorough, and thoroughly enjoyable read all the way through, with far too many merits for me to recount them all here.

“Here is the obvious bridge between the two: the vampire, like Death, is stagnant, everlasting, and a promise of what is to come. Mortality lends itself to Death, and Death willingly and lovingly takes Life into his arms in the final hour. We are at once repulsed by and attracted to this; we shouldn’t long for Death in this way, because it is the lack of everything we have ever known – death is violent, uncaring, Godless, and cruel, the opposite of all that life should represent. But at the same time, Death is secure and promising. Why shouldn’t we embrace what we are, what we will become?”

II. The figurative Meat and Potatoes of it all

"All the different nouns-- she says them in rotation. Death, husband, god, stranger."

By Louise Glück, from “A Myth of Innocence” (collected in “Averno”, 2006)

I wish not to deceive you, now. In all truth, brevity was not a concern of mine when writing this newsletter, my dear. I fully meant to indulge. To be plain: this section of the newsletter will feature an extremely thorough deconstruction and exploration of the “Death and the Maiden” trope (hereafter occasionally referred to as DatM) as I know it, from the paintings it originated in, to an analysis of its individual aspects, and then slowly but surely making our way to modern film and tv, passing by vampires and fairytales and all sorts of delights on our journey. I hope that suits you, my dear— just kidding, you don’t really get a say in anything today. Life is cruel, but I am much crueller! But for a small consolation, a part of the beauty of newsletters is that you get to digest everything entirely at your own pace. I may be cruel, but I do not wish to needlessly exhaust you.

So, first, a little index of the meal for easy reading— I recommend using the search command to skip to the sections you wish to read, or reading in parts. Ingredients:

II.I "Shuffling the Deck" - an introductory note on what the DatM trope entails

II.II "Beauty and the Beast" - parallel story structures of DatM from fairytales, discussing "Beauty and the Beast" and "Bluebeard"

II.III "Death, that Amorous Paramour" - a short history of the anthropomorphised Death, including “memento mori” and “danse macabre”

II.IV "the Anatomical Venus, or, Dissecting the Maiden" - a deconstruction of the Maiden, featuring notes of the “monstrous feminine”

II.V "Dracula and the Maiden" - vampire DatM

II.VI "Beautiful Dreamers" - all about the “watching someone sleep” trope, the theory of the “female gaze”, and DatM power structures

Let’s cut to the chase, shall we?

II.I Shuffling the Deck

“When is a monster not a monster? Oh, when you love it”

by Caitlyn Siehl, from “Literary Sexts: A Collection of Short & Sexy Love Poems” (2014)

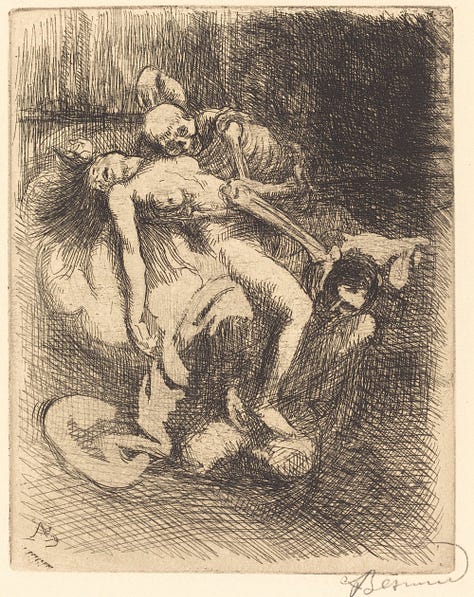

Taken as literally as possible, “Death and the Maiden” refers to a trope in which a personification of Death interacts with a “Maiden”, or young girl. The trope centres on the unique perspectives these two, at first glance, seemingly polar opposite figures have, and the ways in which they might find common ground, or influence one another. Most often, the trope is interpreted romantically (and that is what I will be focusing on): some of the oldest DatM tales from around the world took the form of stories about the fearsome Death taking a mortal wife.

In its purest form, the DatM trope involves a personification of Death, but Death does not have to be Death. Rather, “Death” can also be someone, most often a man, involved with darkness, death, and evil— see for example Heathcliff in “Wuthering Heights” (1847), or the Phantom from “the Phantom of the Opera” (1910). However you spin the wheel, what matters is the juxtaposition of “Death” with the “Maiden”: the pull of the dark and the warmth of the light. The Maiden then is a near-personification of good or innocence, in the sense that she is not literally meant to be an anthropomorphised version of these traits, but rather somebody in strong possession of them, characterised by them.

In “Wuthering Heights” (1847), Death is present both in the characterisation of Heathcliff as a foil to Cathy, and as a third-party force of nature, indefinitely lurking on the damp moors. Whereas Heathcliff is a brute and a savage to everybody else in the novel- he hangs dogs, schemes and manipulates, and later on even beats his son- he exhibits the oddest endearments in the company of the spirited, impulsive, occasionally-cruel Maiden Cathy— an interesting spin on the Maiden we will discuss in-depth later. When she is on her deathbed, he oscillates wildly between cursing her fragility in having to die at all, and imploring her not to leave him behind: “You said I killed you – haunt me then! […] Be with me always – take any form – drive me mad! Only do not leave me in this abyss, where I cannot find you! Oh, God! It is unutterable! I cannot live without my life! I cannot live without my soul!” (from “Wuthering Heights”, by Emily Brontë, 1847, p. 169). Later on, he goes as far as to dig up Cathy’s coffin, taking a lock of her husband’s hair out of her locket, and replacing it with a black lock of his own. The force of death comes to the Maiden, and the narrative’s personified Death mourns her deeply.

It is to be noted that the “Death” character is often portrayed or seen in a sympathetic manner, especially by the Maiden. He is conflicted about his evil nature, or he might feel trapped within a cycle of his own cruelty. The Maiden interests him because she is so unlike him, is a symbol of life, youth, innocence, goodness, virtue. She in return might feel intrigued by his nature, or feel the need to help his escape his own torment. Either party might disguise their interest in the other with pretend-hatred or denial: a lot of modern DatM stories follow an “enemies to lovers” structure. Regardless, the two characters are irrevocably drawn to each other, connected. The possible endings for their eventual union are as follows:

the salvation of Death

the corruption of the Maiden

the death of one (or both) parties

The tension in their relationship stems primarily from the looming possibility of the first two options. All the tenderness and cruelty is ultimately a tug of war for which party, Death or the Maiden, will succumb first. The third option- death- then, is the tragic one. Always looming in the background, on the edges of the storybook, ready to pounce. Even when you think the story has reached its climax, when either Death is redeemed or the Maiden irrevocably changed, death is still on the menu. In fact, the effect of it is all the greater and more tragic if it strikes right after the aforementioned transformation. And we as the audience, are supremely aware of this. When Mina begs Dracula to turn her in the 1992 film adaptation of “Dracula”, it is not her soul we fear for. No, we as viewers desire for Mina to get what she wants: to be turned by Dracula so she can be with him forever. It is the consequences right after that which we fear. The real threat is the third party, the hunter, the killer of the dream.

Enough distractions. Now that we have a basic framework, some necessary components, the endings we are all hurling towards, we can start actually deconstructing the trope as we see it. Starting, of course, with a game of dress-up.

II.II Beauty and the Beast

“The bear loved the deer, it was obvious. It ripped the deer's throat out, and then licked the dying deer with the most passionate affection. I thought of you and me.”

by David Cronenberg, from “Consumed” (2014)

Monstrous men and virtuous virgins are nothing new to storytelling. In fact, the “Death and the Maiden” trope can be so closely aligned with two classic fairytale story structures that they’re nearly synonymous of one another— those stories being “Beauty and the Beast” (~1740), the closest match, and “Bluebeard” (~1697), which shares the same components, but almost entirely eliminates the first possible ending, the redemption of Death. Both of these story structures feature their own maniacal, evil, brooding men, and your typical heroines, fragile but brave, feminine, and inquisitive. Let us examine these stories now.

In the traditional “Beauty and the Beast” story, as recorded in French by de Beaumont in the 18th century, and later by Charles Perrault, Beauty or Belle is a young maiden (see what I did there?) living with a gaggle of stuck-up sisters. When her father loses his fortune because of the loss of his merchant ships in a storm, the family is forced to live in squalor. Beauty adapts well, but her sisters do not. A few years later, her father receives word that one of the ships did indeed survive and made its way back to port, so he sets off to meet it. Before he leaves, he asks each of his children what gift they would like on his return. The sisters naturally ask for all kinds of lavish excesses, while Beauty requests only a rose. Instead of a ship, the merchant finds nothing, and making a detour in his melancholy, he ends up at a mysterious magical castle. Long story short: he steals a rose from the premises, a humanoid but monstrous Beast appears, enraged, but he lets the merchant go in return for one of his daughters, Beauty sacrifices herself and joins the Beast, they eventually fall deeply in love, mortal trials and tribulations ensue, the Beast turns to a human prince, the end. And they live happily ever after.

In the story of “Bluebeard”, an innocent young woman marries a wealthy older man (the “Bluebeard” in question), whose previous wives have all mysteriously disappeared. Once married, they take to his castle, where she receives the keys to the palace’s many rooms. Bluebeard, intending to leave his new wife for a small business journey, insists that she may use the keys to open all of the rooms, except one. Of course, curiosity killed the cat, and it’s not long before all the rooms are opened, the final one containing the blood and bodies of all his previous wives. In her frantic hurry to get out of the room, she drops the keys in the blood, and upon retrieving them, finds that they are magically unable to be wiped clean, oh, the terror! Bluebeard unexpectedly returns from his trip early, and it doesn’t take long for him to find the keys blood-stained, damning evidence of his wife’s disobedience. As for the ending, in the most common versions, just as Bluebeard intends to kill her, the new wife’s brothers arrive to save the day. In some, she willingly lays down her life and joins Bluebeard’s cabinet of horrors.

More Romantic in its views than “Bluebeard”, “Beauty and the Beast” traditionally ends with the Beast- who is actually, physically, a beast- turning human and living happily ever after with Beauty (ie. the Salvation of Death). The Beast’s appearance gives a mostly false idea of his character, exaggerating his cruelty. Bluebeard, on the other hand, is a man who appears harmless, and is then revealed to be monstrous all along. The tale ends either with the killing of Bluebeard and his new wife’s narrow escape, or her joining the story’s body count. Either way, there is no redemption— one or both parties has to bite the dust. The similarities between these two tales and the DatM trope are clear: you have one party who is beastly or otherwise representative (and capable of) evil and/or death, and one known for traditionally virtuous (feminine) traits like beauty1, innocence, or goodness.

Both of these stories have real life implications of course. “Beware girls, for your husband might be a beast in disguise!” was a very real outcome for a lot of girls and young women ushered into marriage with men they barely knew. The duality of these tales and these archetypal men, Bluebeard and Beast, was one heavily drawn upon in the Gothic literature of the 19th century:

“‘Bluebeard’ and ‘Beauty and the Beast’ came to nineteenth-century British readers in chapbooks, gift books, and collections along with other seventeenth- and eighteenth-century French fairy tales; allusions to them appear relatively frequently in Victorian texts. In Jane Eyre these two tales drive both the plot structure and the characterization of Edward Fairfax Rochester as some combination of a Beast figure and a Bluebeard figure. Whereas the Beast is a character who initially appears beastly but is ultimately desirable to the heroine, Bluebeard is a character who is less obviously menacing at the outset but ultimately beastly on the inside.”

By Jane Campbell, from “Bluebeard and the Beast: The Mysterious Realism of Jane Eyre” (2016)

Interestingly enough, the “Bluebeard” story is often more damning of the new wife’s disobedience than of Bluebeard’s killing, torturing, and mangling of his wives. And the same goes for “Beauty and the Beast”, where it can be argued that “the Beast;s transformation rewards Beauty for embracing traditional female virtues.” (Archive Source 2). In holding steadfast to her meekness, in being obedient, and in operating restraint, both women, barely heroines, get their rewards. While these two tales both exhibit similar structures as the traditional DatM trope, this treatment of their respective Maidens is in staunch contrast with the possibilities open to her in DatM stories, which we will return to once the Maiden gets her own section. But first, we must talk about Death.

II.III Death, that Amorous Paramour

“I am Death and when I love you, it’s forever”

by Supervert, from “Necrophilia Variations” (2005)

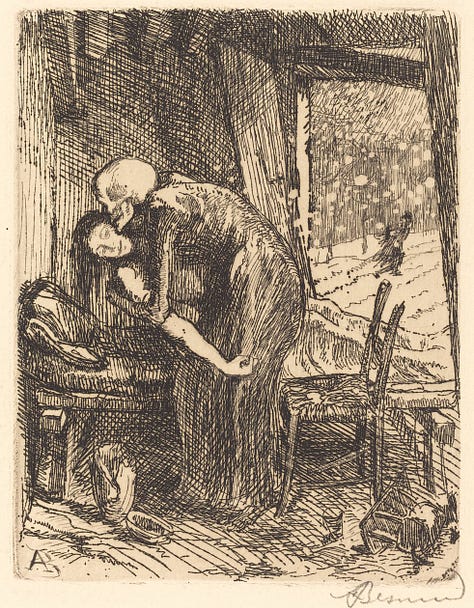

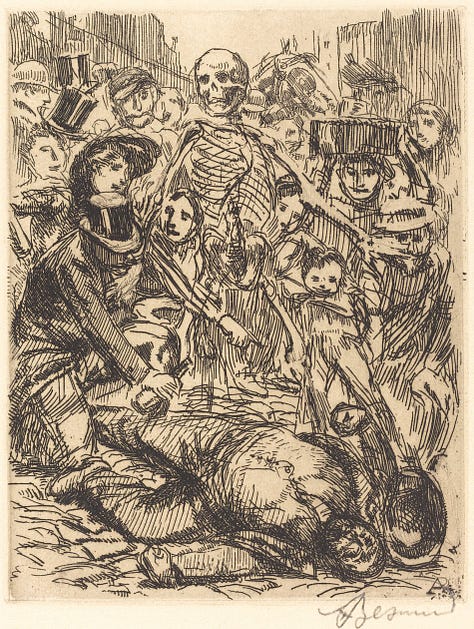

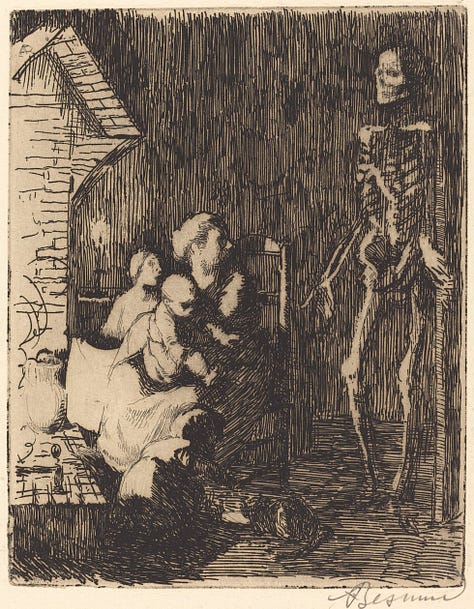

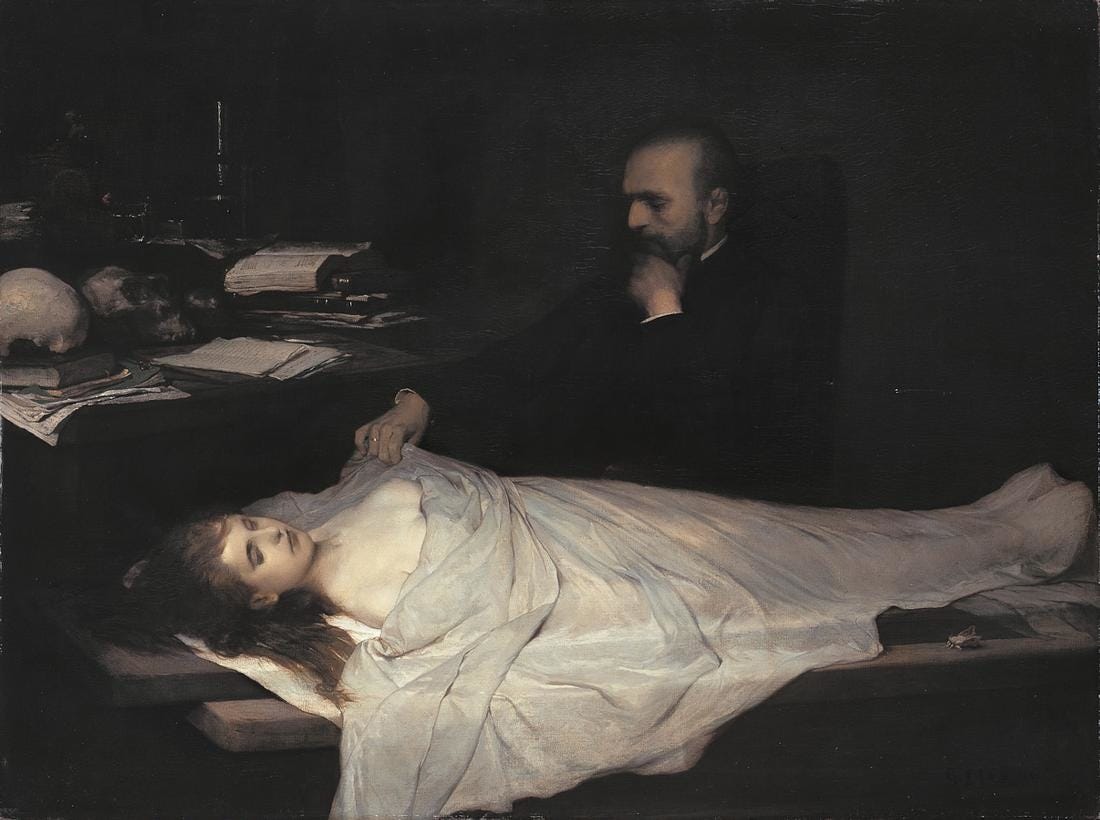

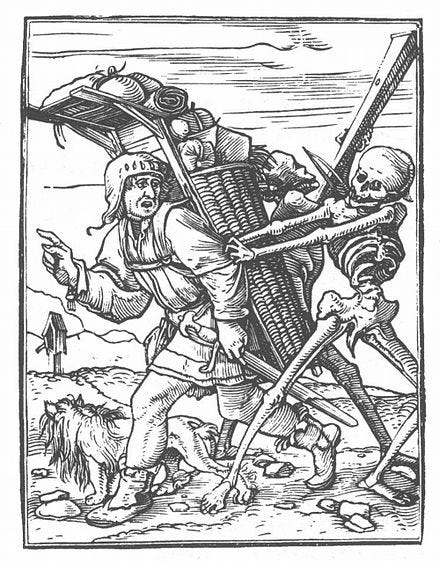

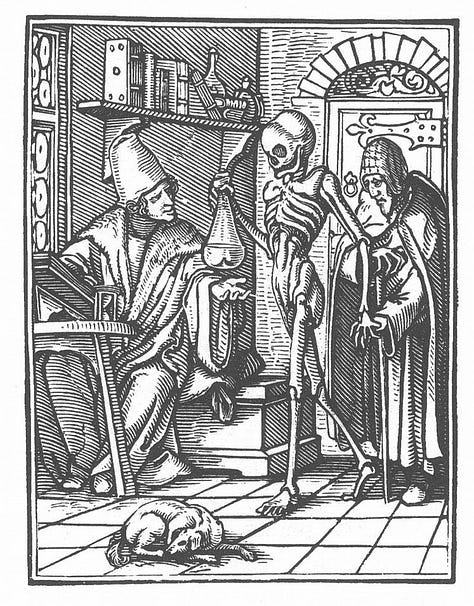

We’ve already touched briefly upon stories in which “Death” isn’t Death but rather a bad man familiar with death, but let’s take a look at when he is just simply Death personified in the flesh. It’s time for a little bit of history. You see, my dear, Death has not always been the one we know so intensely. Or at least, he hasn’t always been personified the way he is now: the Angel of Death, the Grim Reaper, the Horseman on his Pale Horse. We weren't always so sympathetic, so understanding, in our views of him.

In the Stone Ages, the very first cave paintings depicting Death often imagined him as a black vulture, or a winged humanoid being. Standing tall, thin, uniquely uncaring in his pursuit of people’s loved ones. That dark Death was seen more as a thief, than as a servant to the natural cycle of life. There simply was no room to imagine him as anything more. Only thousands of years later do we begin the empathise with him. In Ancient Greek mythology, the god of death, Thanatos, is described as a gentle god, who has compassion for the dying. The Romans even went as far as to dedicate a whole month to Death, namely the month of February. Odd, maybe, to our modern conception of February as the month of Valentine’s, the month of love and all things sweet, but then again, the Greek god of death Thanatos was said to be “nearly” twins with Eros, the god of love. And in the Eastern spheres, across their religions, the gods of death and love are often closely related. In Hinduism, “Yama (Death) and Kama (Love) are said to be in eternal union” (by Leilah Wendell, from “Encounters With Death […]2”, 1996). Intersection of Love and Violence, anyone?

“Well, he'll come to your house and he won't stay long You'll look in the bed and somebody will be gone Death will leave you standin' and cryin' in this land”

From a song by Rev. Gary Davis, “Death Don’t Have No Mercy” (1992)

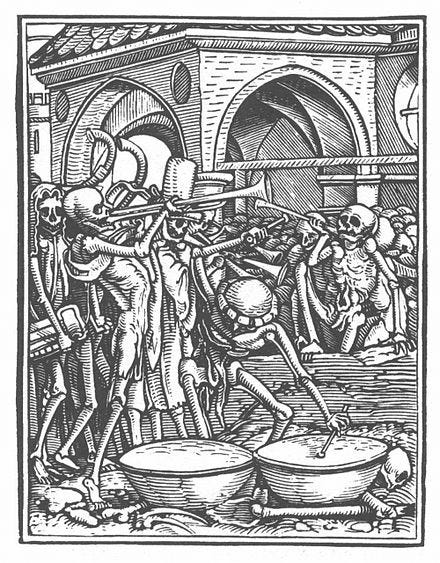

The phrase “Memento Mori” originated in medieval times as a way of reminding humanity that we all must eventually, well, die. With the heavy focus on religion infused into the domesticated culture of the times, the phrase was not meant as a sort of cry encouraging mindless (and sinful) hedonism, but rather a warning for people to prepare for the afterlife. In many ways, our earthly garden of delights was seen as a mere prologue, a tutorial before the real thing, and “memento mori” was the Christian church’s cry to remind the people of Western civilisation that what they did in this short life, decided the course of their eternal life— whether Hell or Heaven awaited their scrawny mortal souls.

Society in general was quite heavily symbolically intertwined with death, and it’s really no wonder. Remember, this is a time where the average life expectancy in England was only thirty-one years old, where doctors operated on people without anaesthesia, and where the Black Plague claimed the lives of almost half of Europe in only a few years (up to fifty million people died!). Mortality was big on the menu, the dead did indeed haunt, and dying was a constant thought in the back of the minds of many people. Thus, themes related to the idea of “memento mori” were abundant in art of the time, as you could reasonably expect to keel over and pass at any time. And what horror it would be to die unprepared.

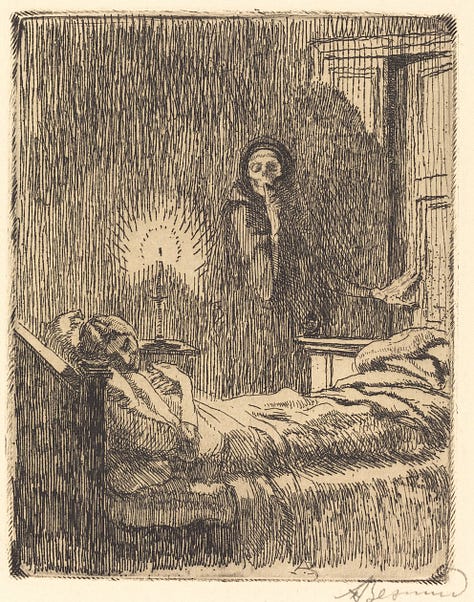

From this sentiment, we get the “Danse Macabre” subgenre or motif within art, in which depictions of Death or his representatives go around reaping souls, or dancing along to the grave with them. Dancing was often woven into funeral rituals, and the idea of the dead dancing was not too farfetched for the beliefs of the era: “During the Middle Ages, the view was quite general that the dead liked to dance, and that they sought to draw the living into their ranks, but, whoever dances with them would die within the year.” (by Leilah Wendell, from “Encounters With Death […]”, 1996). But a skeleton would not be the only form we allowed Death to take within our cultural imagination.

Our idea of Death as an “Angel of Death”, originates largely from Judaism and Islam’s very own Azrael, or the “fallen angel”. The idea of Death wielding a scythe to “reap” or “harvest” souls (therefore; the Grim Reaper) can be traced back both to Jewish depictions, and geographically, to the Slavic and Baltic regions. As the terrors of medieval life slowly faded, Death became more and more of a welcomed friend, especially during the great wars, when his presence was pictured more as relieving soldiers from the grotesque battle they fought in.

And yes, even before then there were plentiful stories of Death in love. As soon as people started writing stories about Death, they included people interacting with him— the very first Death and the Maiden stories. These come from all corners of the world, and there are far too many to start collecting them here. A lot of these are tribal, originating from Africa, but there are also ones going as far back as Ancient Mesopotamia. In a lot of these stories, the Maiden seeks out Death, is curious about him. Sometimes she comes to him to bargain, to strike up a deal, to save a loved one’s soul. Either way, Death is entranced by her, and she by him, and she joins his side forevermore. She teaches him to live, and he teacher her to die. Quite ominous, really, but our fascination with the dead did not slow down. Instead, it grew exponentially over time.

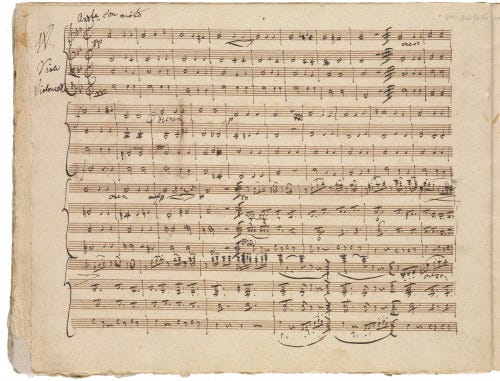

The Romantics were obsessed with death. One needs only read some Romantic poems about love to see all the morbid paraphernalia scattered within their stanzas. Worms, burial rites, tombs, crypts and cemeteries— all were fair game! There is a certain “awareness of the sacred” (from The Penguin Book of Romantic Poetry, p3) woven into the verse of the Romantics, one where there is always an ending of sorts in sight. Sometimes that ending is literal, is death. Of course, every vow of love eternal implies what lies beyond: the dark forever, the confines of the tomb, that gentle lover Death. Combine a penchant for suffering, tragedy, and great heroic love affairs, and you have a poetic movement ripe for DatM symbolism.

And it is rife, if you know where to look. You see, there is lots of Romantic (and by extension, Gothic) writing out there that casts shadows of DatM, but may not actually be about DatM in the strictest sense of the word. There are fifty shades of DatM out there, all equally interesting and complicated in their own ways. Death has always been characterised as a pursuer, or a seducer, from his very first appearances. Some shades simply involves dead girls, plain as that: Death came to the Maiden. Sometimes this is used as a metaphor, to stir up passions under the guise of “memento mori”, like in Andrew Marvell’s “To His Coy Mistress”: “Nor, in thy marble vault, shall sound / my echoing song; then worms shall try / that long preserved virginity, / and your quaint honour turn to dust […]” (ca. 1649-1660). Some of it involves the death of the Maiden, and her lover left behind to mourn her, like in Lord Byron’s poem “to Thyrza” (which was secretly written for a man, but I digress); “Oh! What are a thousand living loves / to those which cannot quit the dead?” (1811). And some do bring in Death in the personified sense, as a competitor for the Maiden’s affections, like in “Romeo and Juliet”;

"Ah, dear Juliet, Why art thou yet so fair? Shall I believe That unsubstantial Death is amorous, And that the lean abhorred monster keeps Thee here in dark to be his paramour?"

by William Shakespeare, from “Romeo and Juliet” (1597). Part of Act 5, Scene 3.

II.IV the Anatomical Venus, or, Dissecting the Maiden

“You think you are possessing me – / But I’ve got my teeth in you.”

by Angela Carter, from “Unicorn: the Poetry of Angela Carter” (2015)

Tragedy is potent, and virtue often comes with a hefty price tag. The Maiden, like other archetypes, has her work cut out for her; “A rose with its role to play” (from “La Belle et La Bête”, 1920). Virtuous characters often get punished by the narrative in which they exist, and the same goes for the Maiden. Death comes to her, not just in the personified form, but also literally: she has to be transformed before she can indulge him, meaning she has to die. But if, as aforementioned, Death is permitted to be complex, both tender and cruel, evil and grief-struck, where is that complexity for the Maiden?

Fret not! While the DatM trope does often manifest in ways that are centered around the performance of archetypal gender roles, the core ideas of the trope allow for more grey area for both parties, especially in modern uses: Death can be tender, the Maiden can be cruel, and both parties ultimately see each other as full, nuanced beings. In fact, it’s the fear of being seen that incapacitates Death in his dealings with the Maiden. When he comes across her, he is confronted with someone who not only interests him, but is interested in him. Somebody who wants to see him, understand him, touch him. And the idea of this frightens him to his very core, it sends shockwaves through the entirety of him. It screams a warning, “Stay away!”. But the odd thing is that no matter how much he tries to, he simply can’t.

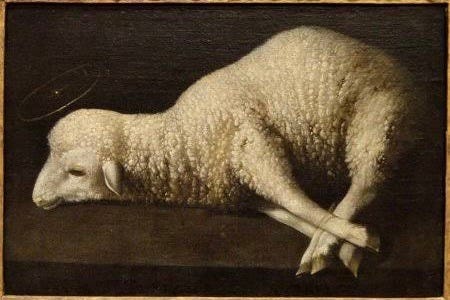

I suppose you could say that Death’s fear of being touched, of being transformed by the Maiden, is actually the fear of [traditional] femininity3. What traits do we ascribe to the Maiden? Innocence, virtue, virginity, tenderness, warmth. It’s the archetype of a woman, really a girl. Clad in white and prancing around, resting her head on a windowsill, face gently lifted up to catch the stray rays of sun. The sacrificial lamb, the lamb of God: “Behold, the Lamb of God, who taketh away the sin of the world!” (John 1:294). One paper5 even goes so far as to state that the couple in love is not really Death and the Maiden, but Death and femininity. This is frightful, for Death believes that if he lets the Maiden into his heart, this will actually grant her power in allowing her to alter him, to influence him, to have control over him.

In the Eastern philosophy of tantra, it is believed that men need to allow the “female” values they have been taught to repress into their life in order to “[give] up the one-sidedness of [their] conscious life, [so that their] whole being will be enriched” (from “Tantra: The Cult of the Feminine”, André Van Lysebeth, 1992). This is the same process that awaits Death, if he gives in to the Maiden’s magnetic pull. No wonder he is terrified! He has been taught to fear all that she represents! The Maiden’s position is then, a position of power. Crucially it is not distinct power over the narrative, or over her place within it, but over him. Her love is transformational. Hey, anything is better than nothing, I suppose.

“[…] every feature of the face of the one we love is beautiful, every word the beloved says is wise” // “Every woman has the power to make beautiful the man she loves” // “Love me and you'll see! To be good, all I ever needed was to be loved. If you loved me, I'd be gentle as a lamb and you could do whatever you pleased with me.”

By Angela Carter, from “the Fairy Tales of Charles Perrault” (2008). Quote from “Panna a Netvor” (“Beauty and the Beast” or “the Virgin and the Monster”, 1979). By Gaston Leroux, from “the Phantom of the Opera” (1910)

Nobody likes a damsel in distress. Or at least, we don’t. As modern audiences, having seen so much, and our senses being so overwhelmed, we practically recoil at the thought of yet another stock character, relegated to being nothing but an object on which horror befalls. A one-dimensional martyr.

Being “a good woman” within a given story is most often simply the absence of evil, not necessarily actively doing good. Simply being a woman with positive traits is enough to be the bearer of all suffering, if only with the goal of making the audience flinch. This is a brick in the wall of patriarchy, of course. Women are seen as weaker just by virtue of their sex, therefore they are always lesser than, and thus they are immediately victims. Still perfect under the enormous weight of tragedy, of course, but still ultimately a victim, and it suits the beasts of her circumstances fine that she is so perfectly undeserving of the horrors: “The piety, the gentleness, the honesty, the sensitivity, all the qualities she has learned to admire in herself, are invitations to violence: all her life, she has been groomed for the slaughterhouse. And though she is virtuous, she does not know how to do good.” (from “the Sadeian Woman and the Ideology of Pornography”, by Angela Carter, 1979, p. 63). The placidity that women are taught essentially only grooms them for misfortune. That is, of course, not necessarily a flaw in the damsel itself— it is the world which is cruel in taking revenge on her so-called weaknesses. But then again, the damsel can easily be lifted out of simple victimhood by being active6. In actively choosing good beyond just the appearance of good, any damsel can gain a little bit of depth, can become true, can become the Maiden.

Sure, the Maiden can also just be a damsel: in the many painted or sculpted portrayals of DatM, there is no depth to either party. There is only Innocence and Evil, Youth and Death, Female and Male. But a successful exploration of DatM gives that depth to both parties. A Maiden who chooses to be good, or who indulges in the darker sides of herself. Death in contrast as tender, protective, loving even. And between the two of them, some perverse blooming sense of understanding.

A large part of why our good Maiden could possibly be drawn to Death is because she feels an affinity for him, feels a close relation between herself and the monster. An inexplicable otherness that comes from existing in a patriarchal society: “[…] there is a sense in which the woman’s look at the monster… is also a recognition of their similar status as potent threats to vulnerable male power.” (from “The Monstrous Feminine: film, feminism, psychoanalysis”, Barbara Creed, 1993). Both Death and the Maiden have the power within them to disrupt established power systems within the traditional male-focused society through their otherness, but the Maiden can also make use of the very femininity she has been cast in, the very image she inherited, the weaknesses prescribed onto her by virtue of her gender alone.

I’ve written before that it can be liberating for women and feminine presenting people to turn the tables around7, to go from the hunted to the hunter, and nobody understands this better than Angela Carter. In her book “the Bloody Chamber” (1979) she collects a whole host of dark, Gothic fairytale retellings focusing especially on the “monstrous feminine”. This term, coined by Barbara Creed in her book “The Monstrous Feminine: film, feminism, psychoanalysis” (1993), is used to signify not just the antithesis of the “male monster” (ie. the “female monster”), but specifically a monster whose identity as female / feminine is the threat itself: “The reasons why the monstrous-feminine horrifies her audience are quite different from the reasons why the male monster horrifies his audience. […] As with all other stereotypes of the feminine, from virgin to whore, she is defined in terms of her sexuality. The phrase ‘monstrous-feminine’ emphasises the importance of gender in the construction of her monstrosity.”

Female characters are often defined by their femaleness first. In video games, there is talk of protagonists, and when strafing from the norm, female protagonists. Maleness is assumed. In tv and media, a headstrong woman is always a strong female character, never just a strong character. Even living in the world, women live their lives as women, not granted the privilege of simply being human first and foremost. Even the language of the world excludes them: humanity, mankind. Up until recently, a Google search for “synonyms for manly” yielded results like brave, courageous, and bold, while a search for “synonyms for womanly” served you with voluptuous, curvaceous, and shapely.

For Carter, she writes that she “spent a good many years being told what [she] ought to think, and how [she] ought to behave, and how [she] ought to write, even, because [she] was a woman and men thought they had the right to tell [her] how to feel […]. So [she] started answering back.” (from “Expletives Deleted”, 1992) And for her answer, she chooses to let her [female] characters speak with their sharpened teeth, to let them bite back. So, we circle back to “the Bloody Chamber”, because in the midst of her retellings, Carter chooses to write two different “Beauty and the Beast” retellings: a traditional one, in which the beast turns human at the end (“the Courtship of Mr Lyon”), and a subversive one, where beauty turns into a tiger like her beloved beast (“the Tiger’s Bride”). It’s a wonderful, dazzling tale of self-acceptance, and one of my favourites in the book— here’s a sample of the very ending:

“He dragged himself closer and closer to me until I felt the harsh velvet of his head against my hand, then a tongue, abrasive as sandpaper. ‘He will lick the skin off me!’. And each stroke of his tongue ripped off skin after successive skin, all the skins of a life in the world, and left behind a nascent patina of shining hairs. My earrings turned back to water and trickle down my shoulders; I shrugged the drops off my beautiful fur.”

by Angela Carter, from “the Tiger’s Bride” (collected in “the Bloody Chamber”, 1979)

This is not the only time Carter lets her female protagonists be uniquely grotesque and monstrous. In her version of Bluebeard, the narrator is consistently skating the knife’s edge when it comes to corruption: “When I saw him look at me with lust, I dropped my eyes but, in glancing away from him, I caught sight of myself in the mirror. And I saw myself, suddenly, as he saw me, my pale face, the way the muscles in my neck stuck out like thin wire. I saw how much that cruel necklace [he gave me] became me. And, for the first time in my innocent and confined life, I sensed in myself a potentiality for corruption that took my breath away” (from “the Bloody Chamber”, Angela Carter, 1979). It’s important to note here that it’s not Bluebeard’s conduct towards the protagonist, or her surroundings that make her cruel. Rather, the cruelty is a trait that has always existed within her, waiting to be unfolded. It’s not a potentiality to be corrupted, but a potentiality for corruption.

We’ve previously mentioned a Maiden before who was cruel and spirited, in the form of Catherine “Cathy” Earnshaw from “Wuthering Heights” (1847). According to Sandra M. Gilbert and Susan Gubar8, Wuthering Heights is a novel about heaven and hell. Following this idea, it is easy to see Heathcliff as devil, seeing as he is often cast as such even within the narrative itself, but Cathy certainly is no straight-forward angel, and she knows it too; “If I were in heaven, Nelly, I should be extremely miserable… I dreamt once that I was there [and] that heaven did not seem to be my home, and I broke my heart with weeping to come back to earth; and the angels were so angry, that they flung me out into the middle of the heath on top of Wuthering Heights, where I woke sobbing for joy”. Straight-forward Maiden, Cathy is not.

Sometimes, the stereotypically virtuous traits of the Maiden are further to be found, and she becomes almost a femme fatale-esque character. In Margaret Atwood’s poem “Marrying the Hangman” (1976-1978), a woman is sentenced to death by hanging for stealing, and knowing that she can escape this death by marrying the hangman, she sets out to convince the cellmate stationed next to her to fill the empty position; “She must transform his hands so they be willing to twist the rope around throats that have been singled out as hers was, throats other than hers”. She might not be a femme fatale in the sense that she leads men to their own death, but she leads this one man to the many deaths of others. The marriage between them becomes, through layer of symbolism, actually a marriage between Death and the Maiden, between executioner and wife.

Narratively, it makes sense for the Maiden to have some edge to her. While it may initially be her innocence, her goodness, her purity of heart that draws Death closer to her, there has to be something to truly hook him. What better than a fiery temper, strong intellect, and a quick wit to match? We can’t all be all morality all the time, darling, that would be incredibly dull! To nail oneself on the cross is lame unless it has another layer to it- of irony, or otherwise- but a simple martyr is not a satisfying character. If a character never grows beyond victimhood then we tire of them quite easily, and quite fast! Better to adapt and survive, to make opportunities, to charm your way to the life you desire. It’s only natural: Persephone, whose relationship with Hades plays out at first like a most traditional DatM narrative, is after all, both the goddess of spring, and the queen of the underworld. She gets the best of both worlds, literally.

And it’s that frightful duality that we both quiver at, and desire— becoming in that desire almost like Death, matching his intrigue, his fascination, his insatiable need to “figure her out”. Death wants an equal, not just easy prey.

“The tiger will never lie down with the lamb; he acknowledges no pact that is not reciprocal. The lamb must learn to run with the tigers.”

by Angela Carter, from “the Tiger’s Bride” (collected in “the Bloody Chamber”, 1979)

Transformation has been a cornerstone of the story- when it comes to the Maiden’s side at least- since the dawn of time. When Persephone is taken by Hades in the original myth, she is merely a girl, picking flowers and singing her gentle songs. But when she returns from the underworld, she is a woman, with all the implications that brings. “Persephone returns home stained with red juice […]” (by Louise Glück, from “Persephone the Wanderer”, collected in “Averno”, 2007). To play at inhabiting the role of the Maiden, Persephone in particular, has been a liberating rite-of-passage from girlhood to womanhood since ancient times. In Ancient Greece, there is evidence of soon-to-be-wedded girls depicting themselves as Persephone, and their partners as Hades, on small terracotta plaques, quite literally inserting themselves into the story to make sense of their own looming transition from the known to the unknown, with the small relief that like Persephone, they can always come home.

In Athenian burial rituals, girls who died before they could be married were sometimes dressed up as “brides of Hades” and their tombs were filled with wedding gifts. Not necessarily in the sense that were sent to actually be wed to him, but rather to rewrite their tragic deaths and garner favour with Persephone: “Following premature, and often horrible or violent, deaths, many girls become ‘Brides of Hades’, and their deaths are described as marriages.” (by Ellie Mackin, from “Girls Playing Persephone (in Marriage and Death)”, 2016). Once more, the story structure of Death and the Maiden is used as an empowering tool, to rewrite reality into something more assuring, to transform what would otherwise be just senseless tragedy into something resembling comfort. The mantle of Maidenhood is liberating to women because of its many shades.

“I am both / the sacrificial lamb and the executioner. / the scapegoat and the swordslayer: / the one screaming and the angel of death”

by Bilal Al-Shams, from “Sacrifice”

II.V Dracula and the Maiden

“Christian anxieties: not simply that we are the hapless victims of absurd, violent, dehumanizing and dismembering fates, to be devoured and dissolved back into brainless nature, but that, succumbing to the vampire's temptation, we are complicit in our own fate. Something in us wants to be seduced, violated, transformed; our innocence, like our virginity, torn from us.”

by Joyce Carol Oates, from “the Aesthetics of Fear” (1998)

When in search for Death and the Maiden references, one needs to look no further than vampire media to find a veritable treasure trove of Death/Maiden pairings. This is because vampires are terribly well-suited to the DatM trope simply by virtue of their species, their supernatural thirst for blood, their seductive qualities on maidens, both real and fictional, within the story and within the audience. Riddle me this: if vampires are supposed to be monsters of the most horrifying proportions, why does our cultural purpose for them often centre entirely around romance?

The original story of Dracula as written by Bram Stoker is seen as a “masterpiece of forbidden desire” (by Joanna Ella Parsons, from the introduction to “Doomed Romances: Strange Tales of Uncanny Love”, 2024), as well as a horror story about transgression and fear of the other. Indeed, the story of Dracula railed against aggressive Victorian norms to create a story dripping with fright… and romance. Two seemingly polar opposites, except that they are, of course not. It’s the Intersection of Love and Violence, my dear. This is home turf.

“Sex is associated with fright” (from “Death and the Maiden in 20th Century Literature and Visual Arts”, by Adriana Teodorescu, 2015) and “repulsion and fascination coexist [in tense feelings]” (Archive Source 3). What haunts us is what intrigues us, what is unknown to us we wish to understand, and what seduces us is what frightens us— both make the heart beat quicker. Dracula, and his predecessor Lord Ruthven from John Polidori’s “the Vampyre” (1819) transgress through the sensuality they awaken in their otherwise prim-and-proper society victims. The much-frightened vampire is a charming, effeminate, sensual creature, here to steal your wife away right from under you! “This wanton sexuality of monsters is not primarily feared because of the damage it may do to the hapless women involved, but because it is an affront to male sexuality [and property]” (by David J. Hogan, from “Dark Romance: Sexuality in the Horror Film”, 1986).

And yet it fulfils a double female fantasy: one in which multiple suitors are indubitably in competition for your affections alone, and another layer in which it is the supposed quality of the main man itself which is the fantasy— cultured, wise, dangerous, sensual, otherworldly. “Vampire boyfriends are noteworthy for their extraordinary ability to be all things at once” (by Ananya Mukherjea, from “My Vampire Boyfriend: Postfeminism, "Perfect" Masculinity, and the Contemporary Appeal of Paranormal Romance”, 2011). This perfect, vampiric man is out there, somewhere, and he thirst only for you…r blood. And maybe if you’re lucky, undying companionship is in the cards as well. Who knows. Either way, what an exciting ride! Just read what iconic actor Bela Lugosi had to say about the reception to his role as Dracula;

“Women wrote me letters. […] Letters of a horrible hunger. Asking me if I cared only for maiden's blood. […] And through these letters, couched in terms of shuddering, transparent fear, there ran the hideous note of-hope.

They hoped that I was DRACULA. […] It was the embrace of Death their subconscious was yearning for. Death, the final triumphant lover. It made me know that the women of America are unsatisfied, famished, craving sensation, even though it be the sensation of death draining the red blood of life.”

by Bela Lugosi, from “the Feminine Love of Horror” (1931)

It’s easy to see how this dynamic then morphed with time9 into the restrained sexual brooding of modern YA vampires, like Edward Cullen from “Twilight” (book, 2005, film, 2008) or Stefan Salvatore from “the Vampire Diaries” (2009-2017). These are vampires who are innately protective of their lovers, despite the paradoxical conflict of interests in which they both want to protect her from their dangerous world, and draw her in closer all the same. But no matter how much he resents his own nature, narratively, the vampire represents death. He is constantly at war with his own urge to kill his very own Maiden, to gorge himself on her delicious, warm blood- blood that calls out to him every time he dares be near her- and that means the tension his presence creates is the tension of being close to death at all times. Or rather, he is Death. When he is not repressing the part of himself that yearns for violence, he is indulging it elsewhere, killing elsewhere. Just because it happens off-screen does not mean it doesn't happen.

No matter how the plot tries to go about it, the vampire is a villain because his existence is unnatural. Drinking only animal blood does not excuse one from the act of killing. Vampires are interesting because they’re complex, and yes, I suppose a part of the appeal is in being a beacon of light for their tortured souls (or lack of soul) to attach to. In part because there is power in that status, in being someone’s reason to be good. There is so much brooding and yearning in vampire romance, because there are such strong emotions on the other end of the spectrum involved: passion, lust, excitement. Bataille wrote that “passion fulfilled itself provokes such violent agitation that the happiness involved, before being happiness to be enjoyed, is so great as to be more like its opposite, suffering”. (From “Eroticism”, 1957)

Whether the vampire is perfectly self-immolating to his own desires like Stefan Salvatore, or perfectly incendiary 24/7 like his brother, Damon, main character Elena Gilbert (who dates both brothers on and off again throughout the Vampire Diaries’ eight seasons) becomes a symbol of human goodness to both of them, even when she is, in fact, no longer human. Damon goes as far as to claim that Elena’s love makes him a better man. And in return, she gets what she always wanted, “a love that consumes [her]. […] Passion, an adventure, and even a little danger” (3x22 “the Departed”). The Maiden gets to redeem Death to a certain extent, and the both of them can know and see each other without pretence in the way. That is the allure.

There are a lot of ships in “the Vampire Diaries” that tick all the DatM boxes perfectly. But while Elena as a Maiden does have some bite to her, and the hatred-fuelled early season tension between her and Damon practically sparks off the screen, I would be remiss in not mentioning the fan-favourite pairing between Klaus and Caroline. Fine, I will admit that it’s totally selfish indulgence on my part, but we’ve come this far without it. Let me have this one.

Anyway, Klaus and Caroline’s interactions (and following flirtations) begin at a point in the story in which the thousand year old10 Klaus is the main villain of the show, while Caroline is both freshly seventeen, and has recently become a vampire. For plot conventions I won’t dive into, Caroline is dying of a werewolf bite, and the only thing that can cure her, is of course, Klaus’ blood. Symbolically, this scene where they first meet is framed as a visit from Death himself. Klaus appears in the doorway of Caroline’s bedroom, dressed in black, as she lays feverish and dying in the foreground. Immediately, she expresses a strong disdain of him (“Do you really think that low of me?” “Yes”), something which surely would have spelled out certain death for anybody else in any other scene, but Klaus is instead gentle with her, asking her if she is really intent on dying: “[…] I could let you, die, if that's what you want. […] But I'll let you in on a little secret, there's a whole world out there waiting for you, great cities and art and music, genuine beauty, and you can have all of it, you can have a thousand more birthdays - all you have to do is ask.” (3x11 “Our Town”). Of course, this seductive worldliness is enticing enough, Caroline yields, and Klaus heals her.

Arguably, Caroline’s ongoing interest in Klaus throughout the series, no matter how much she tries to hide it, and his almost obsessive fascination with her, is the exact reason they embody the DatM trope so well. The pairing between Klaus and Caroline, like the one between Death and the Maiden, is stirred up by the forbidden, the taboo. She, and other characters on the show, constantly suppress this desire as something shameful, to be hidden, but that only makes its pull stronger. The same way Edward warning Bella to stay away for her own good only piques her interest more. Bataille wrote that “the urge towards love, pushed to its limit, is an urge toward death” (From “Eroticism”, 1957). Meanwhile, on Klaus’ end, he argues that Caroline’s constant disapproval keeps him in check: “I’ve shown kindness, forgiveness, pity…because of you, Caroline. It was all for you” (4x14 “Down the Rabbit Hole”). His interest in her is a foil to his own monstrous nature: “You're beautiful, you're strong, you're full of light. I enjoy you.” (4x11 “Dangerous Liasons”).

When supernatural fiction first got popular roughly around the turn of the 18th to the 19th century, it was hailed as a “bad” influence on women, especially young girls, whose minds were blank slates, fragile and impressionable (by E.J. Clery, from “The Rise of Supernatural Fiction 1762-1800”, 1995). The feminine sensations of these novels were said to be inferior, and good chunks of that prejudice still lurk today. The truth is that supernatural fiction, especially vampire stories, are tales mostly subjugated to the whims of common female fantasies, tales in which their desires and attractions are wholly taken seriously, even when they’re “not good” (ie. not virtuous) impulses. Combining this with the DatM trope, which allows for an uncharacteristic amount of freedom for both Death and the Maiden in terms of gender roles, tenderness and emotional intimacy, as well as unrestrained displays of passion, it’s no wonder that vampires are still some of the romantic genre’s greatest heroes.

II.VI Beautiful Dreamers

“Dreams do dream us, don’t they? We are not the ones in control.”

by Jeanette Winterson, from “Gut Symmetries” (1997)

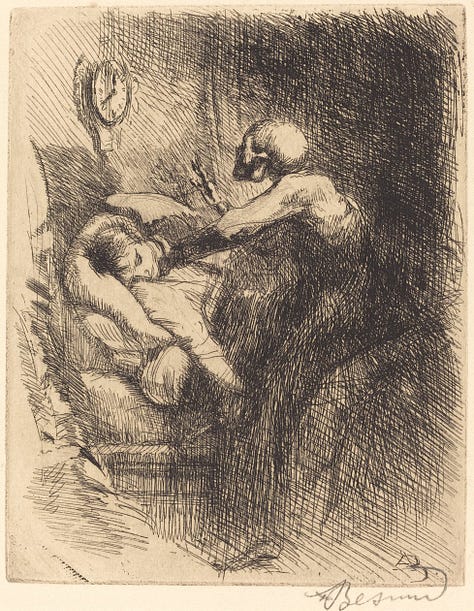

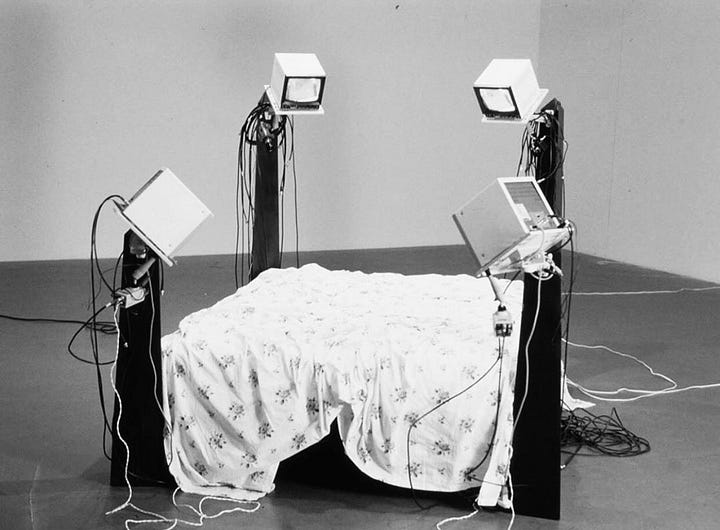

Keen readers might have noticed that the majority of artworks and visuals depicting Death and the Maiden have Death visit the Maiden in a vulnerable state, often in her bedroom, or watching over her when she sleeps. Culturally, the idea of vampires watching their lover sleep (aka the “Beautiful Dreamer” trope), is an established connection within the cultural zeitgeist. Some of these scenes, like the ones in “Twilight” (2008) have become nearly-synonymous which the genre, being often ridiculed, or filed away as “creepy” and “predatory”. There’s a whole world of nuance not permitted simply for the trope being “perverted”. And there is much more ground to cover towards a better understanding of the trope, and more importantly, why it does click for some audience members.

If you’ve been in the video essay sphere at all within the last five years or so, you’ve probably come across the term “[the] female gaze” before (also referred to as the “feminine gaze”). You might already have some idea about what this means. But in the last half century, the “female gaze” has been wildly misapplied, commodified, and watered down from its original context.

Suppose that the feminine experience under the patriarchy is defined by scopophilia, or the idea that one group (in this case, men) derive pleasure from looking at an object or person (ie. traditionally, the “male gaze” is defined by objectification and voyeurism), then the “female gaze” as coined by Laura Mulvey11 is to be looked at completely, without subtext applied.

Monster romance stories, including DatM / Vampire / Beauty and the Beast adaptations and adjacent tropes, are all about perception. Being seen is truly the crux of the trope. The entire authenticity of the relationship between Death and the Maiden revolves around the complete, (mostly) judgement-free image they have of one another. Its vulnerability boiled down to its absolute core: pure acceptance. And that vulnerability goes both ways.

We’ve already seen what it means for Death to let the Maiden in: to open up to all sides of himself. For the Maiden, accepting Death’s gaze means connection with someone who disregards conventional norms, who has no interest in performance, who stands outside of the spectrum of common morality. And that’s endlessly enticing. Performance is a big part of [archetypal] femininity, especially the values and ideas traditionally associated with the Maiden, like virtue. It has even been argued that to be a woman, is to perform, and prune, and purposefully police the self perpetually for the male gaze’s pleasure:

“Male fantasies, male fantasies, is everything run by male fantasies? Up on a pedestal or down on your knees, it's all a male fantasy: that you're strong enough to take what they dish out, or else too weak to do anything about it. Even pretending you aren't catering to male fantasies is a male fantasy: pretending you're unseen, pretending you have a life of your own, that you can wash your feet and comb your hair unconscious of the ever-present watcher peering through the keyhole, peering through the keyhole in your own head, if nowhere else. You are a woman with a man inside watching a woman. You are your own voyeur.”

by Margaret Atwood, from “the Robber Bride” (1993)

This is where the female gaze, and the beautiful dreamer trope intersect. Realistically, the dreamer is not performing. However, to us, the viewer, they are— the image of them is curated and polished within the media we consume: the dreamer is a mark of innocence, the emphasis is on how radiant they are without even being aware of it, flawless even when gently asleep. This is why Mulvey described the cinematic experience as a voyeuristic one, the viewer fundamentally separated from the screen, essentially looking into the image instead of at it, and constantly projecting onto it in return.

But within the plot conventions that facilitate for the Beautiful Dreamer trope to happen, for one to sleep and another to watch them sleep, it is a moment meant to be uniquely disarming. It is the very antithesis of performance. The dreamer might never find out about the other party’s watching over them. The interaction is devoid of spectacle, and then as the scene gets translated to the screen, and it has to be packaged for consumer view, that is when the other layer of aesthetics gets varnished on top. This is essentially a protective layer with the potential of warping the interaction, robbing it of its sweet joy. Adding a third into this dynamic, the viewer, emphasises a perverted sort of voyeurism that isn’t initially there in just the text, but gets added in the translation process.

In “Twilight”, Bella doesn’t simply exist as an object for the viewer, or Edward to gaze and gawk at. Instead, she is primarily the one looking: “Edward's glance only later meets her originating gaze; with him, she is rarely the "looked at," but the one doing the looking or an equal in an exchange of glances - except at night, when Edward sneaks in simply to watch her sleep. (But we only see that when she wakes suddenly and catches him, so we never share his point of view of her vulnerable body)” (Archive Source 1).

That Bella is at alternating points looking and looked at does not mean she is devoid of power one moment and in charge of it the next. All of these individual moments exist on a spectrum, and have to be taken in within the context of the narrative in which they exist. After all, it’s all fictional, and one must remember that “The vampire nature of the characters and the fantasy element in these stories make these actions more believable, but they also make qualities desirable, which, in actual men in real relationships, might be quite unsettling.” (Mukherjea, 2011). Of course, being watched while you’re sleeping would be genuinely unsettling to the majority of people, if it happened to them in real life. But this is fiction, and we have to play by fiction’s rules when we interact with it on its home ground, whether that is the screen, or in text.

In “Buffy the Vampire Slayer” (1997-2003), there are several moments in which Angel watches Buffy sleep, and they all carry wildly different subtexts to inform how the viewer should feel about them. Because “BtVS” overall has a more grounded tone, the standard instances of Angel’s voyeurism are supposed to be viewed with skepticism, and are met with a restrained romanticism in the framing of the scenes, and a contrasting almost-humorously unsettled tone in the characters’ later reaction to them. When Angel loses his soul and turns evil, his watching Buffy sleep is now a threat, and the show makes no overtures in hiding that fact. The subtext informs the viewer how to read the interaction at face value.

The Beautiful Dreamer trope requires a different amount of suspension of disbelief for everybody, hence why some enjoy it, and some do not. Regardless, humanity in these stories is often linked to fragility, and that fragility is expressed partly through the ability to dream. When Bella finds out that Edward doesn’t sleep, can’t sleep at all, the confession is met with disbelief, and apprehension, for it is proof of otherness. Up until that point, all of the vampire lore is far removed from Bella, and the audience, but sleep is sacred to humanity— after all, Stephanie Meyer dreamed up the initial story of “Twilight”.

Sure, the dead can be associated with sleep through their methods— the vampires from “Interview with the Vampire” (1976) famously sleep in coffins. While vampires may be iconic for their various haunts in the night (like Heathcliff’s rambles on the moors in “Wuthering Heights”, 1847), they are not seldom associated with dreams themselves. Rather, when Bella visits Edward in the night, it has the added subtext of him missing a hunt, missing his meals, literally missing his nourishment in choosing to visit his love instead. Dracula visits his “victims” when they are most vulnerable, tossing and turning at night. The core of the Beautiful Dreamer trope is, in this way, built on vulnerability, a genuine lack of pretension: the vampire Death reveals who he really is to the Maiden in visiting her in her own home, her own safe space. There’s a freedom from the eternal performance of the self, and a romantic need for closeness, for tenderness. Death and the Maiden, as a trope, like vampire romance, is built on these same core principles, and it is thus that the three tropes so often mix and intertwine.

And that’s all for Death and the Maiden. For today, at least.

III. A word for an Anniversary

“It's all romanticism, nonsense, rottenness, art.”

by Ivan Turgenev, from “Fathers and Sons” (1862)

If you’ve come this far, I salute you, and I itch to wish you a happy first anniversary of the Substack12! Of course, I have chosen some words to celebrate. I promise not to get too sappy on you. No drool or anything.

When I started this newsletter one year ago, it was purely a passion project for me, a way to take the research-fuelled limited madness of my Instagram write-ups to long-form content and pair it with personal updates and more. I never, ever, could have imagined that any of this would resonate with as many people as it has so far. God, I always think I sound so insufferable in writing, but I need you to understand that I’m not joking in the slightest when I say that each and every time somebody interacts with this newsletter, or the White Lily Society, I feel so incredibly touched and joyful.

When I started writing that very first newsletter, I had no idea what it could possibly become. That it would become a way for all of us to connect, to share and contribute, that I would write entire theses for fun just to deepen my interests. I think that, in a lot of ways, there is something so special about this community we are all a part of, this loving monster we are all helping shape. This past year has been so uniquely validating, and extremely healing for me, and for that, I wish to thank you once more.

I would be lying if I said I wasn't brimming with a million ideas on where to take the White Lily Society, each one more ambitious than the next. I would love to start organising some casual events very soon-ish, a few meet-ups or picnics for my fellow White Lily Society members here in London. Keep your eyes open for a bunch of Death and the Maiden themed submissions, and more things happening over on Instagram. As always, there’s a plethora of question marks to be discussed as well. And who knows, maybe Death and the Maiden III is still in the cards. I’m sure there are many things I haven’t quite mentioned, or touched upon, or even thought about, and many things I’ve had to cut for time (yes, really).

But for now, I simply want to wish you a happy anniversary. Here’s to many more years!

“Every time I want to write, I want to write love stories. But as soon as I pick up the pen I’m overcome by horror.”

by Margartia Karapanou, translated by Karen Emmerich, from “Rien ne va plus” (1991)

My dear, I fear there is little more to say, and nary a creak of space left in the crevices of my brain for me to squeeze out. In my writing of this newsletter for the past week, I’ve forgotten how to live in the world, a girl who loves her books and her monsters and her reading. Suppose this newsletter is a testament to written dilly-dallying, then. August is fresh on our doorsteps, eternally promising my beloved overcast skies and refreshment of the soul. I’ve always been more fond of the colder months than of the white heat, but the only way out is through. Something bad in the air, I suppose, and I just feel so terribly fragile under the sun’s scorching rays. Despite everything, there is an endless deliciousness to be found in the haunting, delicate, ephemeral darkness we inhabit. It’s simply intoxicating. As for dessert, I’ve deferred my Yorkshire travel adventures to next month’s newsletter, so stay tuned for that. I figured you would have had your fill by now.

Happy anniversary, my dear.

Affirmations for August (repeat after me)

I am the beast of melodrama and excess

They could never strike the whimsy in me dead

I will not succumb to the horrors of the sun

Until my next letter,

x Sabrina Angelina, the White Lily Society

Currently reading: “Bones and All” by Camille DeAngelis // Most recent read: “Wuthering Heights” by Emily Brontë

White Lily Society links // Sabrina Angelina links

It’s never too late to jump on the bandwagon and join the White Lily Society for more Romantic ramblings, tea-fuelled academia, and Gothic-tinted frights. Come, become a martyr of deliciousness.

Virtue is often associated with beauty, and whiteness, among other things. In the Renaissance it was believed that one’s appearance was a reflection of the soul, as beauty was bestowed on the individual by God, and thus “ugly” people must be morally inferior (National Gallery of Art)

Full title “Encounters with Death: A Compendium of Anthropomorphic Personifications of Death from Historical to Present Day Phenomenon”

See Brigid Burke, “Death and the Maiden: The Curious Relationship Between the Fear of the Feminine and the Fear of Death”, 2019

Using the 21st Century King James translation of the Bible

From “Death and the Maiden in 20th Century Literature and Visual Arts”, by Adriana Teodorescu, 2015 - link

This is something I also touched on in Newsletter “09. Took an Arrow to the Knee”

See Newsletter “09. Took an Arrow to the Knee”

From “The Madwoman in the Attic: The Woman Writer and the Nineteenth-Century Literary Imagination”, 1979

It’s interesting to note that at a time when most relationships were not allowed to be openly sexual (ie. the Victorian era), vampires were distinctly lustful, whereas in our modern hyper-sexualised landscape, vampire romance seems to focus most strongly on consent, restraint, and emotional intimacy first.

All [vampire] romance requires a certain disconnect, a suspension of disbelief, especially when it comes to the age of the characters. "To some extent, the reader must accept this appearance of youth as just as valid as the vampire/man's actual age; otherwise, his relationship with a young woman loses its romance in becoming perverse" (by Ananya Mukherjea, from “My Vampire Boyfriend: Postfeminism, "Perfect" Masculinity, and the Contemporary Appeal of Paranormal Romance”, 2011). Luckily, vampires in media don't often act their age, meaning it's easy to filter out this fact while you're watching, minor references aside, but the willingness to practice partial amnesia depends on every individual audience member, and likely reflects in how much you enjoy the genre.

In “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema”, 1975

the White Lily Society itself turns two on October 26st

This was beautifully written! Thank you for this masterpiece < 3

hi ! i am the author of "gentleman death in silk and lace." i'm so glad you liked my thesis :)