27. Demi-Monde

Fantasy is always very fragile, after all.

“I believe Octobers are created to tell us that life bends towards us everyday. That when I lock eyes with a stranger, there’s a wild desire to bleed for love. That when I bold things in my trying hands and not pick at the edges, I can keep the pressure for all its worth.”

by Dion Anja, from “October” (collected in “Motion Sickness” (2022)

[TW] This newsletter deals (among other things) with the sex work of 18th and 19th century courtesans, including Cora Pearl, who was sexually assaulted as a precursor to becoming a courtesan. This is mentioned briefly without any details whatsoever, and not further elaborated on in Section II.I. No graphic language is used. Reader discretion is advised, as always.

01/10/2025, London, UK

My dear,

It seems that somewhere along the way, jumping from letterbox to letterbox, this letter got a bit lost. These things happen when writing long-distance musings, I fear. Strange disappearances in the fog… Not even a postal stamp could save those who are dead set on straying from the path.

October is the month of the dead. Month of incoming cold, trees starting to strip, sun taking its leave. No more blackberries past-Michaelmas. September was all poetry and rose pouchong tea (happy birthday to me!). Perfumed cruel intentions, wrapped in silk stockings and garters. Reading in the embassy waiting room, booked twice a day, luxuriating in delirium— a phoenix of downtown social events. Getting psychoanalysed on my couch until a live mouse disturbed. Unfortunately I do love the crushing weight of yearning, I do love melancholy, I do love candlelight dramatics. Nothing else has ever suited me better. Method research meant inhabiting the courtesan before writing about her.

Everything new and shiny must always be laid out for my finest patrons. Allow me the honour. Two new “Death and the Maiden” themed poems made their way to the spotlight, one by yours truly based on Lucy Westenra, and another channelling the quiet lace despair of girlhood. And though lifting the curtain is not always in the best interest of a humble writer, a prose performer, I did also take on the infamous “Proust Questionnaire” to celebrate my birthday on the 10th of September. With that said and done, let us trade one delicacy for another, and dive into the world of courtesans.

The fineries are only just beginning…

‧₊˚🖇️ ✮⋆˙ ₊˚💌⊹⋆。𖦹 ° This newsletter contains the following sections:

I. Archive Sources // II. Grandes Horizontales (on courtesans) // III. Gathering ghosts (a birthday recap) // “On the List” October // Outro

I. Archive Sources

“I advocate glamour. Everyday. Every minute. Glamour above all things.”

by Dita von Teese

This rotation of archive sources, I must confess, represents a slightly more ambitious version of this newsletter, long lost. Once more I have fallen victim to my own inability to be concise, the remnants of which you will find here. Where, at first, this letter was supposed to cover courtesans, showgirls, and burlesque, I was soon forced to drop the latter two for brevity’s sake— do forgive me, my dear. A fraction of them remain to read about here, little teases for what I’m sure to revisit in the future. A very glamorous, bedazzled Chekhov’s gun.

“SHOW BUSINESS: The Glorifier: Florenz Ziegfeld and the Creation of the American Showgirl” - link

Writing of the classic revues perfected by Florenz Ziegfeld, this paper talks of his invention of the “showgirl” as we know it. Essentially, Ziegfeld took the French idea of the revue and Americanised it, injecting it with lavish glamour and the era’s optimism, to create a show equally outrageous, voyeuristic, and wildly popular. But the fantasy of the Ziegfeld girl was entirely built on their distance; the show itself was a play of strategically revealing and hiding. Silk stockings much preferred over bare legs. And these showgirls did not need an array of talents to embody this fantasy, most of the “mannequins” had little task but to look pretty, wear exquisite outfits, and walk gracefully. The show would do the rest, my dear.

“Before Ziegfeld, most Broadway revues used about twenty chorus girls who made three costume changes during the show. Ziegfeld was determined to move well past those limits. He would make his revue so large and lavish it would become an entirely different experi-ence-something to be marveled at rather than merely watched. In Marjorie Farnsworth’s phrase, he would create in his audiences ‘a feast of desire.’”

“Embodied Transformations in Neo-Burlesque Striptease” - link

This paper takes a look at the world of Neo-burlesque (starting in the 1990s) and compares it to the early burlesque of the 1920s, 30s, and 50s. It posits that the added ingredients of tease and wit to an eroticised display of [female] flesh make neo-burlesque a powerful conduit for transformation. Neo-burlesque itself is a transformation, in act and in presentation. It is both nostalgic in its imagery, producing the accoutrements of a “long bygone” era of glamour, and meta-reactive in the way it often winks at itself and the audience. This is a core tenet of its philosophy; existing within what was once simple a tool for the mere display of female flesh, but expanding on its under- and overtones to largely divorce the performance from pure voyeurism.

“While the act of undressing outside the site of performance is generally perfunctory in nature, the desire to produce laughter in response to disrobing the female body suggests both an element of intent regarding how the performance is received and a capacity for change in how the spectator views striptease performance; it can be mocked, ridiculed, and celebrated.”

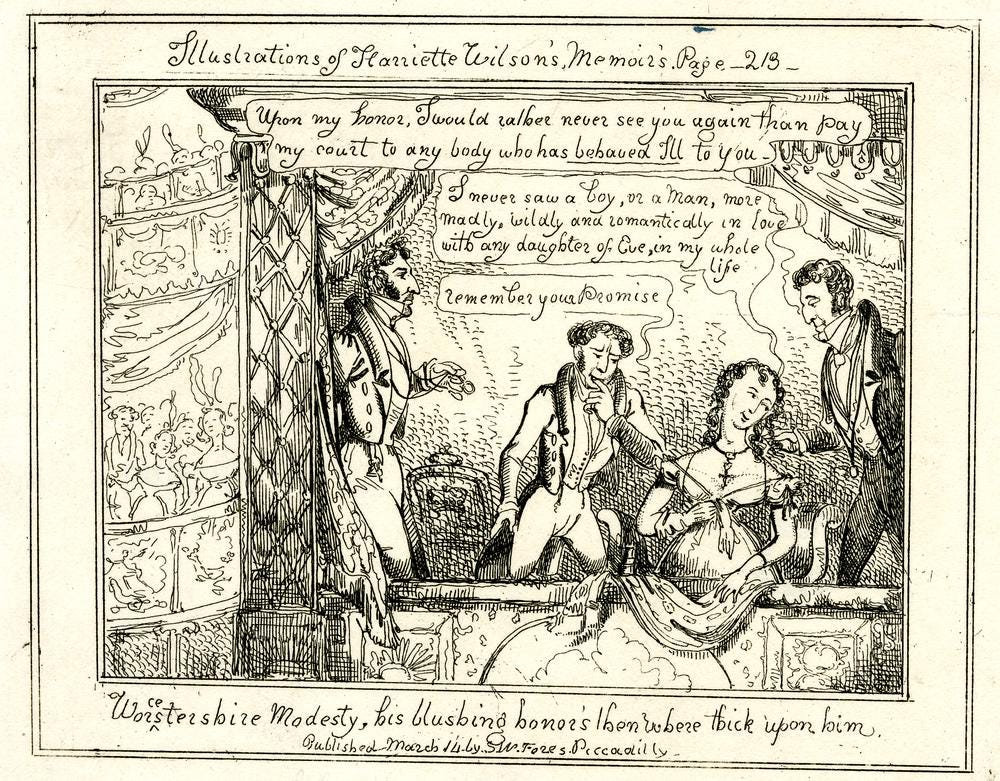

“‘All the men admired her, and many of the women envied her’: The Role of Dress in Portraits of Eighteenth-Century British Courtesans, 1751-1790” (Chapter 1) - link

Through a thorough examination of the courtesan Kitty Fisher’s dress in her portraits, this chapter establishes a central theme in the courtesans’ social standing, and how, visually, it was hard to distinguish members of the monde (polite society) from those in the demi-monde (half world containing courtesans etc.). These demi-mondaines or demi-reps constructed their myths through careful assimilation of status symbols such as fine fabrics or jewellery, but also through associations with the boudoir and “undress”. It posits that courtesans like Kitty seduced both men and women alike through their distinctive freedom, outrageous antics, and luxurious lifestyles. Not in spite of their inhabiting the demi-monde’s “shadow” world, but because of it.

“The high level of visibility of prostitution in general, and higher still the exposure of such diamond-draped high-class mistresses and courtesans, must have within the general population to some degree ignited a desire for emulation […] But so excessive was [Kitty’s] outward display of cultivated opulence that she was accused by moralists of “seducing [women] from the paths of virtue by her display of luxury.””

Grandes Horizontales

“Mansions, diamonds, carriages! … What gilded dreams!”

by Cora Pearl, from her memoirs, taken from Katie Hickman’s “Courtesans: Money, Sex and Fame in the Nineteenth Century” (2003), p228

There are only two bookmarks in my well-worn copy of “the Art of Seduction” (2001), my dear. Despite my gratuitous breakfast, lunch, and dinner re-reads, only two sections have proven themselves crucial enough to be marked, to receive that distinguished honour. The first is irrelevant to our story at hand— it marks the chapter in which Lord Byron makes his appearance, to nobody’s surprise. But the second, more important one, is a haphazardly dog-eared page marking the start of chapter twelve. That delicious favourite of mine, so often poured over. Scripture, really. It is the chapter on “poeticising” one’s presence.

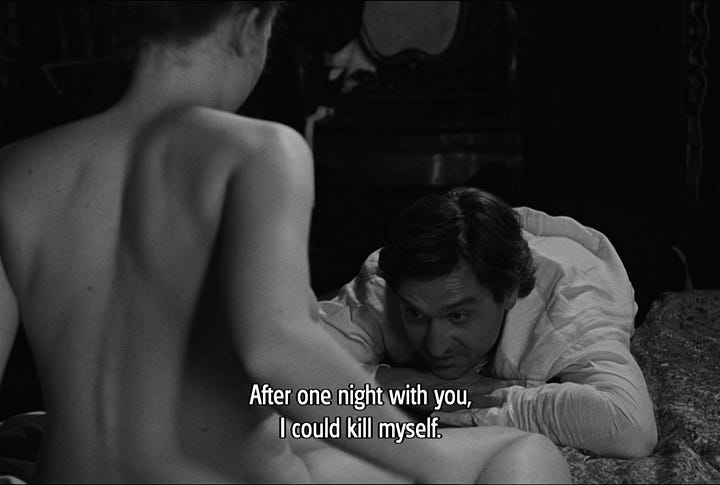

It is a chapter all about the mythology of the self, the poetic symbols we choose to align with, and their effects in the war of seduction. A pantheon of the proper symbols can elevate anyone into a conduit of pure eroticism, can make attraction sizzle where there was none before. To give another person the gift of someone or something to fantasise about is a selfless, ambitious pursuit. Fantasy is always very fragile, after all. Embodying such an amorphous thing is extremely strenuous. And yet, there was a group of women in the 18th and 19th century that had fantasy down to a science; the courtesans. To this day, the courtesan is an image of hedonism, of seduction, and of glamour. The very word brings to mind silks, the scent of roses, and initials on powdered stationery.

Who better to learn from about the game of seduction?

II.I Mad, Bad[deley], and Dangerous to Know!

“Part of the allure of the courtesan, I think, is that she has always been an ambiguous figure. She is not a mere prostitute, although she is unequivocally a ‘professional’ woman who accepts money in return for sexual favours. […] Neither is she a mistress, who usually considers herself the lover of just one man […]. A courtesan always chose her patrons, very often for her own pleasure as well as theirs. Her gifts - of company and conversation as well as of erotic pleasure - were only ever bestowed upon a favoured few, who paid fabulous - sometimes ruinous - sums for them”

by Katie Hickman, from “Courtesans: Money, Sex and Fame in the Nineteenth Century” (2003), p3-4

The word “courtesan” stems from the Italian and French feminine forms of “courtier”, or the English verb “to court”, which means to woo, to curry favour with, to pursue. Garishly misleading for our beloved courtesans, those idols of contradiction! No, these women were neither prey, nor hunters. Men came to them, sought them out. But make no mistake; the courtesan was the one with her finger on the trigger. The choice of patrons was, ultimately, entirely hers, my dear. Unlike the name of her profession suggests, she had to be sought out, courted, pursued. Never the other way around. Safe to say that the chameleon nature of the courtesan was built in from the very start.

The 18th and 19th century were the [European1] golden age of the “kept” woman, the mistress on the payroll. Previously, the practice was associated primarily with kings, plying their lovers with castles, the finest dresses, and jewellery. Think of Diane de Poitiers or Mme du Barry, royal favourites with the finery to match. But now, at the onset of the 17th century, any well-off gentleman could reasonably afford to do the same, both financially and within the elasticity of his reputation. It’s no wonder that some clever women took to making a profitable career out of it! The art of being the other woman was born; the courtesan-as-status-symbol. The more famous, the more expensive. And these women were both exceedingly famous, and disgustingly expensive.

At the height of their careers “on the town”, the most famous courtesans could command entire fortunes on a whim (Laura Bell was once given the equivalent of £12 million2 to spend a single night with a prince, and Cora Pearl’s household expenses totalled £56k in just two weeks). They relished in unparalleled luxury and freedom, which in turn allowed them to be picky when choosing their protectors. Make no mistake, boiled down to the most basic of its many ingredients, being a courtesan involved the simple sell of sexual favours for money— with a twist of ultra-exclusivity. But courtesans made long-term deals; they did not trade in nights but in years. Their successful careers could last decades, and they were not shy about it.

Some, like the famous courtesan Cora Pearl, saw their continual string of uber wealthy high-society suitors as a “chain of gold”, their proudest achievement. It helped that the practice of the courtesan was not hidden into alleyways and seedy brothels, but elevated into the company of royalty and aristocracy. The French courtesan “La Barucci” kept a bowl of visiting cards by her fireplace containing every high-ranking individual one could imagine, all the men who had sought out her charms, her company, and to line her pockets in return. But this does not negate that the heart of the practice was built on the respectable idea of exclusivity; courtesans oftentimes signed contracts that entitled them to life-long annuities (sometimes even post-breakup!), but also demanded loyalty and monogamy to the male benefactor of their choice. These settlements could last years, decades… or until either party grew restless.

Shadows defined the “demi-monde” of the courtesan, the glimmering half-world over which they reigned, even if it existed in partial overlap with the “monde” or polite society. Just because courtesans often mixed with aristocrats and royalty, does not mean they were de facto embraced by them. Metaphorically, at least. The physical embrace it a different story, my dear. It was one thing to attend certain balls, or have a box at the opera… as long as one didn’t mix with the wives of their patrons.

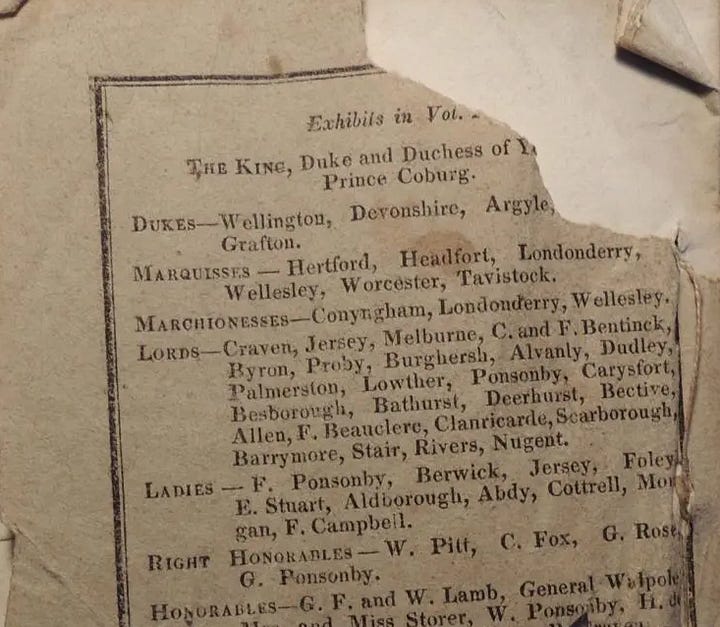

The world of prostitution was paradoxically meant to be hidden, but in practice was much more public. On the one hand, guides like “Harris’ List”, which rivals the French “Guide Rose”, spoke quite plainly and openly about the world of prostitution, both low and high end, and how a man might partake in it. But on the other hand, men were still expected to make “introductions” to courtesans through their connections. The cold approach was a big faux pas. The demi-monde’s debauchery, unlike common prostitution, was surreptitiously half-walled off from the public. It had to come to you. As a result, lots of people knew of it from whispers and gossip, but much less actually partook in its impropriety.

Women could take a plentitude of different paths to becoming a courtesan, some of them much more traumatic than others. Sophia Baddeley was a stage actress turned courtesan, Elizabeth Armistead came from a high-end brothel before she became more “exclusive”, Harriette Wilson was seduced by the demi-monde’s promises of freedom, Julia Johnstone was cast out by her family after falling pregnant out of wedlock, Cora Pearl was assaulted and decided to make the of her now “ruined” prospects, and Catherine Walters ran away from the convent she was raised in. These women came to be some of the most well-documented, famous “grandes horizontales”. They immortalised themselves, crafted a mythology of silks and pearls and gentleman hearts broken along the way. They made themselves into forces of nature.

Some paths were still more common than others; to be an actress or performer was already largely synonymous with being a prostitute3, and so it often took very little effort to blur the lines from the stage to a career “on the town” (ie. as a prostitute of any caliber). In fact, most of the prime actresses of London’s fashionable theatre district on Drury Lane in Covent Garden lasted only a few seasons on stage before retiring to become the kept mistresses of various high society figures. Noticeably, Covent Garden was dense with both theatres and low end brothels— the high end brothels that started the career of courtesans such as Elizabeth Armistead were mostly centred around King’s Place in the St. James neighbourhood of London. Within a stone’s throw of their wealthy clientele.

These high-end brothels closely resembled the French tradition of ultra-extravagant brothels set by the likes of le Chabanais and la Fleur Blanche. These English “nunneries”, as they were called, were lavish and exclusive, and allowed only the highest of society in. They prided themselves on the education of their girls, both in the erotic arts, as well as in those of conversation and of grace. A modern education, for a modern girl. Day to day “nunnery” life included a constant stream of increasingly outrageous private events involving copious nudity, crazed amounts of champagne, and generally ensuing debauchery, continuing well into the morning. It is not hard to imagine how such a place could give one both the connections and the education to go private, so to say.

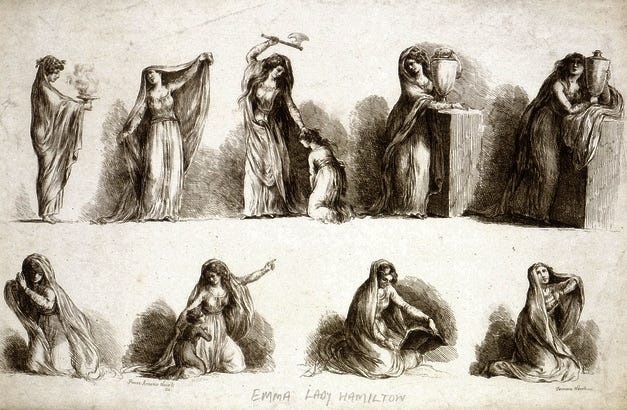

Though not all courtesans were actresses (by trade, at least), more than a handful started their demi-monde career in the stage spotlights. This includes Sophia Baddeley, one of the most outrageously famous courtesans, and Emma Hamilton (born Emma Lyon), whose story is quite unique, as far as demi-reps go. You see, somewhere amidst her successful career, Emma encountered a horrible turn of events, that she undoubtedly managed to turn to her absolute advantage. Coldly bartered from one man to another with little say in the matter, she made herself a title and a legacy. The situation was this; Emma’s then-patron, Charles Francis Greville, wanted to temporarily rid himself of her in order to marry rich and secure his fortune. Much easier said than done, of course. And so, Greville reached out to his uncle, Sir William Hamilton, suggesting that the latter lodge Emma in Naples and take her as his mistress, while Greville secured his nuptials and his riches back in London. Once everything was done, he would return to fetch Emma from her “holiday”.

After about six months and dozens of pleading letters, the realisation of what had happened dawned on Emma. Greville had abandoned her, and while she wasn’t close to penniless, she was now in a strange city and without a protector. Nothing untoward had happened; she had traveled accompanied by her mother, and kept separate apartments, but Sir Hamilton was no doubt courting her intensely. The good faith reading of events suggests that the two fell in love, and were married only five years later— it is not meant to be an assault on Emma’s character when I suggest that this turn of events could also have been strategic on her part. Slyly upgrading herself from Hamilton’s potential mistress to his wife permitted her a multitude of advantages. She got a title, access to court and high society (extremely rare for any demi-mondaine who found herself “elevated”), and, eventually, a doting husband who adored her. She turned a cruel situation to her absolute advantage.

We also have Emma’s ingenuity to thank for the invention of the classic parlour game “charades”, a fun fact for which I’ve always had a fondness. Emma’s life in Naples soon became that of a wildly successful salon host, entertaining her guests with song and game. For her “attitudes”, as she called them, she would dress up and pose, acting out classical scenes for her party attendees to guess at. The game charmed the masses, and even started a renewed interest in Grecian-inspired draped dress. Emma was doing what women in her career path did better and more stylishly than anybody else; playing her cards with the seasoned savvy of a professional, and setting the trends like only her fellow demi-mondaines could. Courtesans like Catherine Walters and Kitty Fisher invented and popularised entire fashion styles. Cora Pearl brought the spotlight down on the first couturier, Charles Frederick Worth, helping to popularise the crinoline, and even had a drink named after her (“the tears of Cora Pearl”)!

˚ 𝜗𝜚˚⋆。☆ II.II an updated recipe for the “Tears of Cora Pearl” cocktail

Unfortunately, the precise recipe for this cocktail was eventually lost to time, but we know it included vodka, crème de violette, and fresh lemon juice in roughly equal measure, topped with champagne. From my experimentation, here’s how I would make it today, to create a cocktail with a lovely soft purple colour, and a floral, sparkling, slightly sour taste, emblematic of a courtesan’s multi-faceted nature:

Combine 30ml vanilla vodka (the original uses regular), 30ml crème de violette (violet liqueur), and 15-20ml of [fresh] lemon juice. Shake with ice.

2. Strain the mixture and pour into the most glamorous chilled flute or coupe glass you own. Top with champagne or prosecco. Garnish with edible flowers or a lemon twist. Sugar-rimmed glasses are also fun to use and add a lovely hint of drama. Enjoy!

II.III a Treatise on the Rights of Courtesans

“Freedom is the most precious gem a courtesan possesses and contain within itself everything she desires. Given this privilege, even infamy seems honorable to her. Since she is not subject to the tyranny of husbands or parents, she can deliver herself to her lovers without fear of being killed for questions of honor. In this way she is free to express natural appetites and feminine lasciviousness.”

by Francesco Pona’s, from “la Lucerna” (“the Lamp”, 1625)

Though courtesans could very much be treated as matters of public opinion, they were also deliberately separated from circles higher than their own by the aristocratic society that was both fascinated and repelled by them. Where courtesans could and could not go was a muddy affair, no part in thanks due to the nature of the demi-monde itself; both spotlighted and concealed. Change only happened through brute force and sheer willpower. When Sophia Baddeley, arguably the most famous English courtesan, was prohibited from entering the high society Pantheon masquerade, fifty of her most ardent admirers and patrons banded together to walk her in, raising their swords at the guards with threats of violence if they did not admit Sophia. From that day on, she had undeniably done the impossible; a blank invitation into whatever social event she wished. It would be a long time before any doors were closed in her face again.

Little others would ever be in the same spot as Sophia, but the life of the courtesan was still one basking in a marked amount of freedom for the time. In comparison to the dull life of wifely duty and the heavy moral constraints on women that developed throughout the era, courtesans had an unparalleled degree of freedom over their lifestyle, who they loved, and how they managed their finances. Granted, only the most exemplary characters could burn long and bright in such a quick-paced environment. The eternal crux of the issue is that celebrity is extremely fickle, and the public a hard mistress to court. But for some, even a small taste of freedom would be enough. Those, such as Harriette Wilson, recognised that despite the pitfalls, there was no other career that could give a girl the freedom, luxury, and pleasure that being a courtesan could. The world was theirs to conquer!

Freedom was what drew women to choose to be courtesans, and men to court them. Their life could be completely and sumptuously drenched in the stuff. Harriette, together with her three sisters Amy, Fanny, Sophia, and close friend Julia (all of them also courtesans) sometimes took to banishing all men for the evening and staying in to gossip and have a sleepover. A display of girlhood, but also of female-led freedom, that still holds power: “[…] unmarried young women together, without a chaperone (or at that point a protector), with their own house, keeping the company they chose and the hours they chose, with the freedom to speak as openly as they wished on whatever subject they wished. No wonder men found them fascinating. Delightfully unencumbered by most of the prevailing notions of female propriety, they had the liberty to be themselves in ways that were absolutely denied to other women.” (Hickman, p155)

The rules of courtship were still largely rigid, and social mobility left things to be desired, even for courtesans. For example, while a [famous] courtesan could request a meeting with practically any man she desired, the opposite was absolutely not true. Men had to go through the trouble of a public “introduction”, usually decided upon well in advance, or they could go to an exclusive “introducing house”, which promised both secrecy and efficiency. Either way, surprising a courtesan or brute-forcing the process was not recommended. Once, after the Marquis of Sligo was bold enough to request Harriette’s private (!) company only one day after their public introduction, she, aghast, sent his servant back with his letter of request, insisting that his Lordship should be more careful to avoid “misdirecting” his letters. The game of courtship was delicate, and entirely fluent, elusive, ever-changing. “This inversion of the normal rules of engagement was all part of a courtesan’s seductive power.” (Hickman, p168)

This is exactly what Robert Greene’s “the Art of Seduction” (2001) posits as well. To seduce, one must inverse aspects of regular courtship. Eagerness and ease are executioners to the heart’s affairs! Some of Greene’s recommended steps include (1) approaching indirectly, (2) sending mixed signals, (3) appearing to be an object of desire, (4) paying attention to detail, (5) poeticising [your] presence, and (6) using physical lures. All things courtesans were sly masters of!

But despite the freedom financed by their protectors, more than a handful of courtesans still found themselves with a gap in their accounts between their promised allowances and their excessive spending. Chief among them Harriette herself, who started accepting the occasional private client into her boudoir, in secret. Luckily for her, the early nineteenth century slowly favoured a higher degree of secrecy in the dealings of extramarital affairs, and particularly the demi-monde. Gossip columns like Tatler or Town and Country’s “Tête-à-Tête” were beginning to go out of fashion. Jumping from theatres, to private brothels, to the secretive introducing houses of the time, the demi-monde became an insider world increasingly hard to enter into, and increasingly opaque in its dealings. This gave the more daring demi-reps a greater amount of freedom to indulge themselves as they wished, without the panopticon of gossip and attention that had previously swallowed up those like Sophia Baddeley.

Alternatively, if one was still metaphorically “strapped” for cash, they could go for the oldest trick in the book; good old fashioned blackmail. Previous courtesans had written their explosive autobiographies before, or had biographies written about them— Sophia Baddeley or Ann Bellamy among them. But Harriette was to elevate the idea of the of the memoir-as-blackmail to a veritable art form, my dear. Her words rained down upon the London scene with a palpable vengeance. Published in separate sections, the ending notes always contained the names of those unlucky souls to be exposed in the next part, giving them a chance to buy themselves out if they had not already done so based on Harriette’s pre-publication “courtesy” letters. For the paltry sum of £10k, the sinner in question could have themselves expurgated from the record. Nobody would ever have to know of their digressions. Despite the lawsuits, Harriette’s memoirs’ authenticity was believed, and copies flew off the shelves; she made an estimated £500k from the whole ordeal! Not a bad side hustle at all…

II.IV a Day and Night in the Life of a Courtesan

“I will be the mere instrument of pleasure to no man. He must make a friend and companion of me, or he will lose me.”

spoken by Harriette Wilson, taken from Katie Hickman’s “Courtesans: Money, Sex and Fame in the Nineteenth Century” (2003), p151

A day in the life of a courtesan, of course, could vary greatly. Courtesans were not monoliths. The one thing they can all safely be said to have agreed upon was an insistence on splendour, my dear. Absolute refusal to compromise. Some, like Catherine Walters preferred rising early, and starting their day with the traditional Parisian crescent rolls and café au lait. On the other side of the channel, one might enjoy a morning hot chocolate, in a luxurious tea-gown or some other state of “undress”, reading the newspapers… Or turning straight to the gossip columns. Breakfast included “coffee, chocolate, biscuits, cream, buttered toasts, tea and Scandal”. (Hickman, p60). But no matter the dishes laid out on the table, it also housed morning caps on standby like weaponry, for one might never predict gentleman visitors.

A small part of the courtesan’s freedom is curtailed by this need to always be prepared, to be available at all times— once, Sophia Baddeley feigned a headache to avoid indulging her patron at her home. She and her ward sometimes took it upon themselves to silently skip town altogether, escaping to fashionable society getaways like Vichy or Bath. But the attention always followed. Sophia, more than anyone, was close to hunted. Her house would be besieged by visitors until two in the morning, and there are plentiful accounts of bothersome gentlemen not taking no for an answer, being a proper nuisance. The most in-demand demi-mondaines could count on a revolving door of visitors throughout the day, no matter if they were with or without a known protector. In fact, being “taken” only increased the interest from men, who longed to outdo one another with outrageous gifts. Throughout history, men have always loved to brag, after all.

In many ways, there was no relief from the performance of being a courtesan; the private sphere was hardly sectioned off from the public. All the world was a stage, even for those who had abandoned their acting careers. I imagine it took a tremendous effort to be on top of setting the trends, the latest witticisms, the latest scandals, even with the burdens of domesticity put onto a staff of servants. The extravagant tricks had to be held up, both planned and spontaneous. The famous courtesan Kitty Fisher supposedly once ate a £100 bill (roughly £30k today), wedged in between pieces of bread, on a whim. Other courtesans could get up to all sorts of antics, fuelling their own mythos. The work of it was relentless.

Getting ready to go out could easily take multiple hours. The French courtesan La Païva reportedly took a daily sequence of three baths; one in milk, one in lime-blossoms, and one in perfumed water. Beyond bathing or getting dressed, the “art of the toilette” also welcomed an ever-increasing line-up of cosmetics going beyond mere perfume: white foundation containing lead or mercury, rouge, “milk of the roses” toner, and pearl face powder were all popular. The look in Baddeley’s time was all about looking as pale as possible, with rosy cheeks, and jet-black eyebrows and/or hair. But by the turn of the nineteenth century, subtler, more Romantic4 looks came into style in response to the French Revolution’s war on excess.

“The thick white lead make-up was replaced by a dusting of pearl powder with a blush of vegetable rouge made from red sandalwood, cochineal, brazil wood and saffron mixed with talc rather than the old and heavy red lead, mercury, or sulphur dyes.”

by Sarah Jane Downing, from “Beauty and Cosmetics: 1550-1950” (2012), p33

Shopping must also have been a great pastime— what other way to spend your considerable fortune, my dear? Trips to the milliner were frequent, and the hauls were repulsively big and exotic. Sophia Baddeley once returned from a shopping trip with eight pristine white mice. The debts, too, were big. True to the times. And they were the downfall of many a courtesan. The demi-mondaines across the pond in Paris had turned the boudoir into a veritable art form; “the romantic negligées and tantalising undergarments, the tangles of silk and muslin, the sheer luxury of lingerie and other accessories would give you goose pimples” (Hickman, p11), and such art came with a hefty price tag.

Paired with silk stockings and corsetry, luxurious dressing gowns, and delicious shadow plays of modesty to stir the imagination, the courtesan was well-armed. Cora Pearl was said to have different outfits for each of her many lovers; matching dressing gowns, slippers, lace nightgowns, and petticoats costing a royal £5.5k per set5, all in the same soft colours and soft materials. Satin, cambric (a delicate cloth, aka “batiste”), French lace, silks, and anything else the heart could conjure up. A most enticing package.

During the day, courtesans made appearances wherever the public’s eye was wandering. These had to be brief, for the schedule was often quite packed and relentless. Exhaustive, even. Mrs Steele, Sophia Baddeley’s ward, once described their regular schedule as such:

“Often, in summer time, have we returned from a place of amusement, at three in the morning; and, without going to rest, have changed our dress, and done off in our phaeton [Carriage], ten or twelve miles to breakfast; and have kept this up for five or six days together without any sleep. In the morning, to an exhibition, or auction; this followed by an airing into Hyde-park; after that, to dress, then to the play; from thence, before the entertainment was over, away to Ranelagh [Gardens], return perhaps at two; and after supper and a little chat, the horses ordered, and to Epsom [?], or some other place again to breakfast […]”

by Katie Hickman, from “Courtesans: Money, Sex and Fame in the Nineteenth Century” (2003), p64

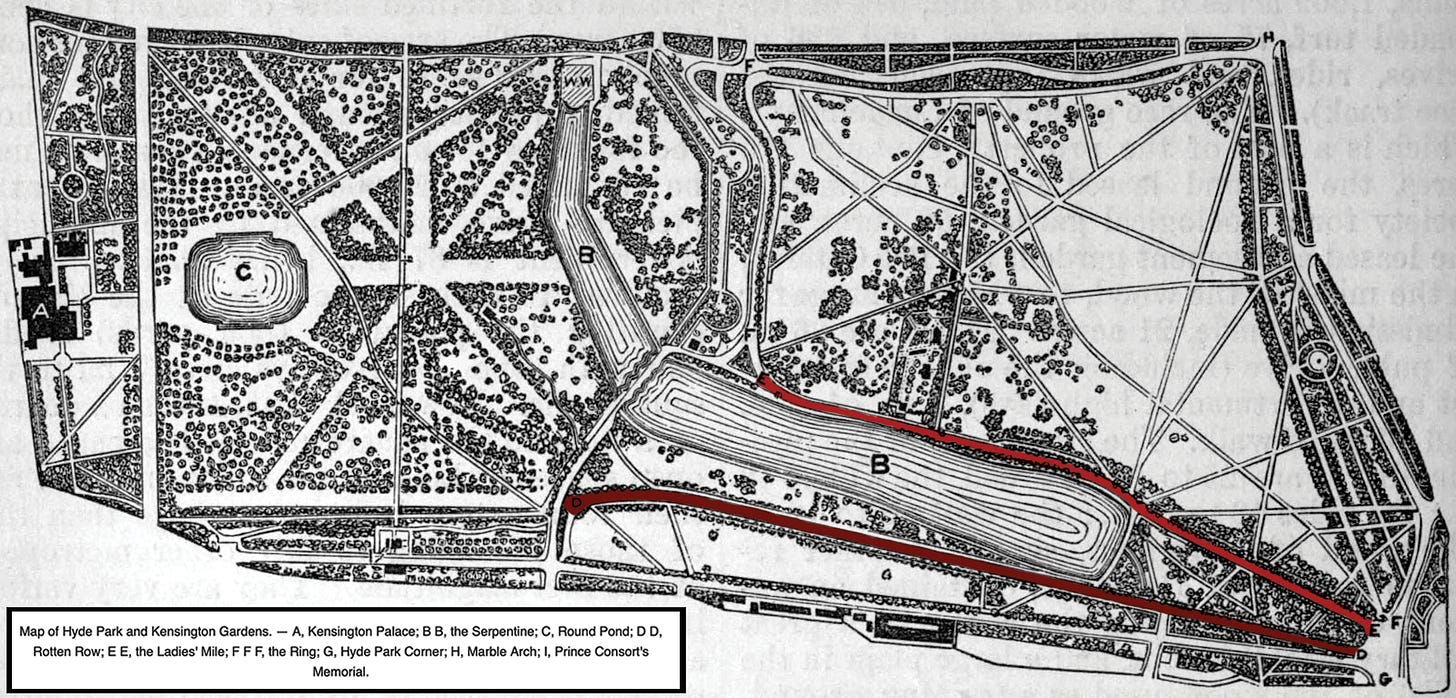

Additionally, it was traditional for high society to meet and promenade in the late afternoon in Hyde Park, from five o’ clock to seven. At first the fashionable procession used to be on Rotten Row, which spans the Southern part of Hyde Park, but moved in the mid 1800s to “Ladies’ Mile”, which spanned the Serpentine. Reports online stated that the latter was still named and marked today, and so, I ventured out to check. A proper lady always checks the facts for herself, my dear! Alas, what disappointment awaited me when I found the majority of paths in the park to be unnamed at present. Answers were divided and contradictory online, and none of them were concrete. My fingers began to itch for the scoop!

I checked the London Archives, to no avail, spent hours furiously theorising. Hope was almost lost, until I stumbled upon a map, which named and marked both Ladies’ Mile and Rotten Row. Thus, my conclusion is as follows: today, you can promenade on the Ladies’ Mile by walking waterside on Serpentine Road until it hits Carriage Drive— you can see the route here on Google Maps, or in the image below. With this slightly conservative estimate of the path, it is more like 80% of a mile, but carrying all that courtesan finery should count for something as well! Walking under the weight of heavy silks and jewellery, and/or slightly inebriated from morning champagne is a proper sport. Not to be underestimated by even the most brilliant of minds. Rounding up shall be permitted.

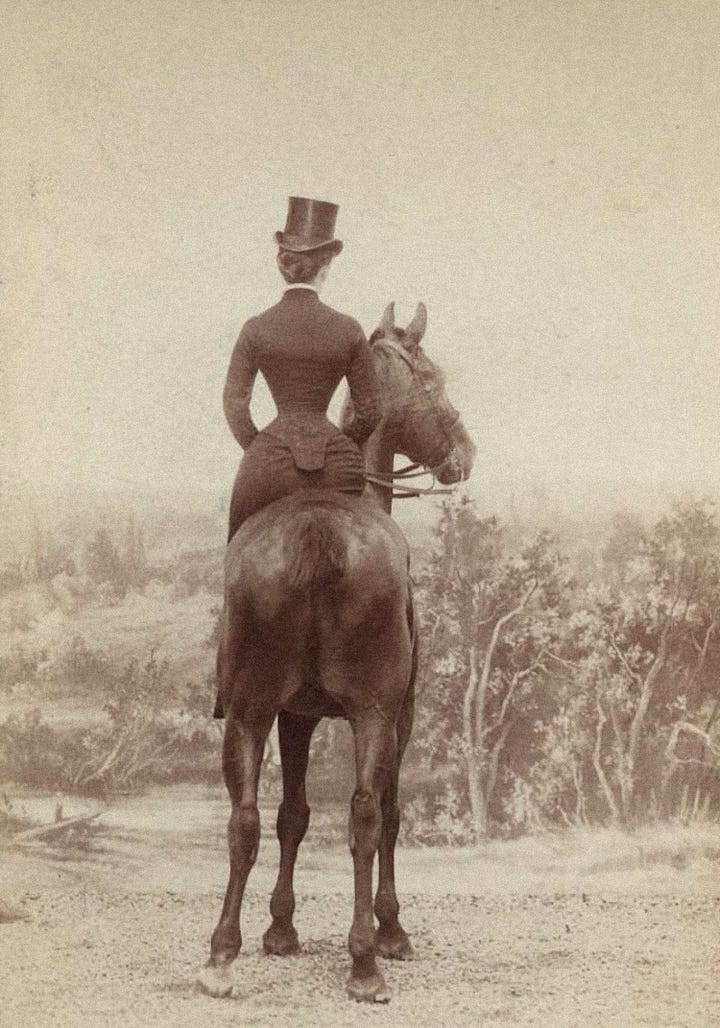

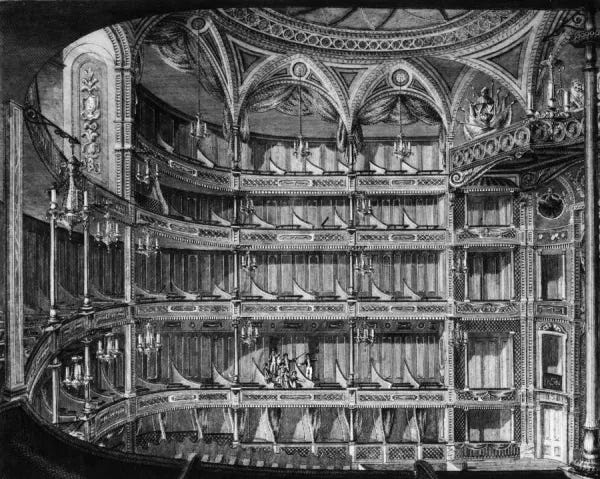

Both Cora Pearl and Catherine Walters loved horses, and took great pride in their equestrian skills. The latter used to ride through Hyde Park, sidesaddle, in a riding habit so tight the people speculated on whether she could even possibly be wearing underwear underneath it. Catherine also adored hunting, a pastime that cleverly put her in the company of many well-to-do gentlemen. A competent business move, as to see and be seen was a goal in and of itself for courtesans. Social life was the key to making introductions, after all. One does not get famous by simply lounging in their well-perfumed quarters, my dear. The vetiver, musk, and civet alone are not enough. They need to be supplemented with regular trips to the opera (private box, of course), masquerades, and pleasure gardens. Nothing but the best will do.

“Cora and her friends, […] would take a box at the Opéra, or the Théâtre des Italiens, where they would appear once a week ‘en grande toilette’, covered in jewels, and graciously consent to receive a few of the more humble of their ordinary admirers […] (with the grave and imposing bearing of ambassadresses taking the air).”

by Katie Hickman, from “Courtesans: Money, Sex and Fame in the Nineteenth Century” (2003), p2

Fashionable opera days were Tuesdays or Saturdays, which left five days completely unaccounted for. But evening entertainment could be much more varied than visits to the operas, theatres, or private balls. Harriette Wilson’s sister Amy, for example, was well-known for her extremely fashionable Saturday evening parties, which were attended by all the notable men in town (sans wives, of course). Alternatively, the great hostesses of the day also organised regularly scheduled parties: Holland House was famous for its glittering dinners, half social event and half political salon. The demi-monde had a strong affinity for imitating the monde or high society, and thus the necessary skillset for courtesans became increasingly wide to match. Advanced etiquette and other hostess’ tricks became essential knowledge.

That doesn’t mean the courtesans were always successful in their imitations. While champagne and liquor were easy to procure for parties (just secure double the amount you need), food was another story. Amy’s aforementioned parties were known for having a never-ending supply of champagne, but thoroughly lacking on the food front. By the time English-born Cora Pearl was making the rounds in Paris, the idea of the dinner party was starting to gain affluence there. No display of wealth was too ostentatious for Cora, who favoured a particularly bacchanalian drama for her events. In the winter months, she had tables full of plump, ripe fruit brought in, laid out on tables of Parma violets (not moss, as was the trend). The violets alone cost her £3k.

If anything, the skills of hosting, of companionship, of dramatics, were the most crucial triptych in the courtesan’s arsenal. The erotic sides were private, ill-discussed. It was the ballroom, not the bedroom, that made stars. The legends of Cora are numerous: she is alleged to have broken her own priceless crystal glass when a guest dropped theirs, just to make them feel better. She danced on the £1k worth of orchids a suitor sent her. Allegedly she filled her bath with vintage champagne and invited her guests to watch her take the plunge. She once served herself, naked, to her party guests on a long silver covered platter carried in by four servants. Arguably, half of these are figments of the imagination, quick-spun inventions, but they carry the poignant essence of demi-monde show[wo]manship within them.

The dubious reputation of the courtesan also made them natural salon hosts, and some courtesans, like Emma Hamilton or the French La Païva took full advantage. La Païva’s salons were held at her home, open to the monde every day, with more select company kept on Fridays and Sundays. Like Cora, she inundated her guests with fairytale spreads of fresh fruit and other impossible luxuries, no matter the season. Reportedly, as one of her guests speculated on the income yielded by her assets, she responded exasperatedly; “Do you think I could give you peaches and ripe grapes in January on [£1 million] a year? Why, my table alone costs me more than that!”6.

It took longer for English evening entertainment to diversify. Restaurants were not a thing, and private evening entertainment really only came in two flavours; long ‘party’ dinners, and late evening balls. These ‘party’ dinners were attended almost exclusively by the mature and elderly— young unmarried ladies retired from eight pm to nine thirty to wake up refreshed before their late night balls. Once more, it was a courtesan who led social change, and Catherine Walters’ Sunday afternoon tea parties quickly became the rival of even the French salons, talking politics and gossip over the same silver tea sets. Scandal goes best with a nice earl grey, don’t you think? It only deepens the flavour.

II.V 2B or not 2B kept

“Cora learnt […] the art of eroticising not only her behaviour in the bedroom, but her whole way of life. Everything about the courtesan, from the way in which her apartment and carriages were appointed to the smallest detail of the way she walked and dressed, was given over to the idea of pleasing men. And it was from this, ultimately, that her power came.

It was no less effective for being, very often, highly artificial.”

by Katie Hickman, from “Courtesans: Money, Sex and Fame in the Nineteenth Century” (2003), p241

There are certainly those out there who attempted to demonise the courtesan as a financial dominatrix, an opportunist preying on poor, vulnerable men, bewitching them into handing over their wallets. But don’t let the morality policing of the Victorians fool you; the image of every woman supposedly being on the brink of being a prostitute is also a fantasy. The pornographic idea of the dominatrix is no less potent than its opposite (don’t make me pull out the Margaret Atwood quote).

The light-hearted tone of accounts of Sophia Baddeley or Harriette Wilson being harassed by an ever-persistent onslaught of men does much to negate the horror of them, but not all of it. The major reason Cora Pearl so suddenly retired is because one of her suitors, Alexandre Duval, upset that she would no longer see him when his payments stopped, tried to force his way into her home not once, but twice. The second attempt succeeded. In the heated argument that followed, he took out his pistol, intent on shooting himself, Cora, or both. Duval survived the bullet, but Cora’s reputation was irrefutably damaged, and she was exiled from France as a direct result.

Gilded rooms, antique mirrors, and vases of fresh flowers could not gloss over the fact that the courtesan (much like the sex worker today) was held in contempt for emptying the pockets of the poor men who were so “helplessly” besotted with them. Never mind the fact that many of these men did try to go back on their deals or weasel their way out of the contracts they themselves had drawn up. This is one of the classic contradictions of the patriarchy; the assumed pedestal of male superiority vs. the argument that they are mere slaves to their lust and/or anger. When a patron of the courtesan Agnes Willoughby wanted to contractually promise her an obscenely high yearly allowance, his family dragged the case to the Commission in Lunacy to have him be declared insane, and therefore stop him from being “taken advantage of”. Surprising no-one, he was found perfectly sane.

The idea that a woman could “hypnotise” a man into doing anything he didn’t want to do was only ever weaponised to eschew male responsibility, and in clear contradiction with the legal and moral treatment of women. In the law, women were on par with children and the insane, with the rights to match. Married women could be divorced, but they could not initiate a divorce, regardless of how her husband treated her. Legally, she was her husband’s property, and much like the servants or the children she was expected to fall in line. Preferably quietly. If their husband spurned them, “deserved” or not, they would be social outcasts. Men, on the other hand, were allowed to separate passionate romances from practical ones; marrying for money and having a mistress on the side was perfectly acceptable, as long as one was discreet. The same could absolutely not be said for women. One mistake on their end often meant living, and likely dying, in destitution.

But within this tight script for women, the courtesan flipped it. She took on the masculine role of the compartmentaliser, the one dealing the cards, separating business and pleasure. These demi-mondaines knew the rules of the game perfectly well, the silver balancing act of propriety, pleasure, and politeness. And they were met with condescension for it, whether subconscious or conscious. The Victorian ideal of the “angel” wife was entirely built upon this; maintaining women as the moral fixtures of the house in order to effectively declaw them. Forced moral high ground is a uniquely isolating place, after all, my dear. The pedestal strips away all value except for purity. The blank slate of forgiveness, understanding, empathy. No bark and no bite. The courtesan Ninon de L’Enclos went as far as to write that “Feminine virtue is nothing but a convenient masculine invention.” Convenient because, in its moral mock-superiority, it kept women chained into what was, in actuality, just submissive inferiority again.

Despite the idea of the courtesan “dominating” financially, intellectually, and (depending on the patron) sexually, being the draw of her services, there is evidently almost always lingering resentment on the male side, ready to engage in a pointless tug-of-war to dominate whenever they feel their pride hurt. Having the Ideal Woman is one thing, but she must certainly not aspire to think of herself as Ideal without the suffix of Woman, without the reminder of her place as ultimately inferior. The courtesan, to some men, was meant to sparkle only as attachment, as status symbol, as object made beautiful by a man[‘s money]. And yet they openly defied all parts of this philosophy. Even laughed at it. La Païva once took a suitor’s offered money and told him she would be “his” only for as long as it would take for the note to smoulder and burn. Her suitor could not appreciate the antics.

A quote commonly misattributed to Oscar Wilde goes; “Everything in the world is about sex—except sex. Sex is about power.” The art of the courtesan was also about power, especially holding onto it, and money served this purpose. Whenever their patrons felt the need to make them jump through hoops, they would refuse to play, precisely because they could afford it. Stop paying and see how fast the door locks. The jewellery, real estate, expensive horses, and other gifts enabled these courtesans to be exactly as selective as they wished to be. If their reputation began to fade, the material spoils of their adventures were their insurance policy (if not reaching for blackmail à la Harriette Wilson). Beyond the initial mythologizing value, many of them sold of their assets from the height of their careers at the end of their lives, to make ends meet. A luxury civilian women couldn’t often count on.

Unlike the sex workers of popular culture- going all the way back to Émile Zola’s “Nana” (1880) and beyond- who must always die a gruesome death as punishment for their wickedness, many famous courtesans died well precisely because they were courtesans. Because they had the connections and money to die a dignified death. Sophia Baddeley died after being forced to return to acting, addicted to laudanum, and in debt, but supported emotionally and financially by her friends and former lovers. Elizabeth Armistead married for love and died happily7. Harriette Wilson died just barely skirting the edge of poverty. Cora Pearl died in exile from France, without the pearls, though supported financially by a club of her old admirers. And Catherine Walters, the last great Victorian courtesan, died at old age from a stroke at home.

The era of the courtesan- subversive, fantastical, and glittering- had come to an end. And with it faded their unique skill to use their desirability as currency. The champagne went flat. Today, the necessity of their career paths is diminished in the face of new freedoms for women, but there are still facets of their lives to desire to emulate. Their inventiveness, assertiveness, the singular precision with which they curated the aesthetic legends of their identity. All of these immensely seductive qualities are what have kept them alive, even beyond the grave. Even once their pearls were sold, the recipes to their signature drinks lost, and their walking routes faded into obscurity. The grand fantasies are immortal, ever-lasting. These myths we weave of ourselves are perhaps the only true immortalities we could ever reasonably aspire to. The story of a banknote burned lasts much, much longer than the fire itself.

“I have never deceived anybody because I have never belonged to anybody. My independence was all my fortune, and I have known no other happiness […].”

by Cora Pearl, from her memoirs, taken from Katie Hickman’s “Courtesans: Money, Sex and Fame in the Nineteenth Century” (2003), p228

III. Gathering Ghosts

“Strength came out of softness and graceful violence;

by Anaïs Nin, from “Mirages: The Unexpurgated Diary; 1939-1947” (2013)

Forgive me, I am running out of words as I write them. For my last grand history of this letter, I wish merely to share the images of my birthday party this past September 12th. Of course, the theme was everything gothic horror; Dracula/Nosferatu, “Bloodborne” (2015), and H.P. Lovecraft— my invitation was a jumbled tangle of references and lore8. It was a splendid night, with no less than ten guests in attendance, all dressed in their best Gothic maiden finery. White nightdresses, rosaries, and lots of black lace, in line with the tragic references I adore. I was gifted with antique glass bottles and vampire fangs and gorgeous candles and a shirt bearing the face of Edward Cullen and compliments that went straight to my head. Bourbon, gin, and prosecco were consumed, together with ripe fruits and cake. I would like to imagine we made the courtesans proud that night.

As a proper hostess, I had ventured to engage all five (if not six) of my guests’ senses. The decorations included wooden stakes, a gratuitous amount of candles, and a swarm of plague rats. “Bram Stoker’s Dracula” (1992) played on continual repeat in B&W on the TV. The soundtrack included the likes of “Bloodborne” (2015), “Nosferatu” (2024), “Mary Shelley” (2017), “Bram Stoker’s Dracula” (1992), and “the VVitch” (2015). My favourite scented candle spread the scent of brown sugar, pumpkin, and cinnamon through the room. Snacks included a selection of Dutch crisps (my ancient heritage), indulgent bacon-wrapped dates, and a delectable fruit platter, complete with everything from cherries to figs. The table was set with a lace tablecloth and the cake, which I made myself, was chai flavoured, with blackberry jam, and a vanilla mascarpone frosting. Everything was a dream.

✧・゚: *✧・゚:* On the List *:・゚✧*:・゚

Exhibitions, Events, and Talks. So, so, so many things to do in this second half of the month, my dear! Just to give you a selection of identities to inhabit; you could attend the launch party for Erotic Review’s fourth issue on the 18th, or attend Aether’s “After Dark” event that same day. You could submerse yourself in a truly indulgent selection of poetry, performance, and music at the new “a Woman Becomes a Wolf” event on the 19th. Or you could luxuriate in Avice Caro’s soft folk music on the 21st. Finally, you could attend a Samhain ritual on the 30th, or you could make your way down to the Benjamin Franklin House to see yours truly perform some spooky poetry. Choose wisely.

Furthermore, the British Library is hosting a talk on Oscar Wilde’s postmortem reputation tomorrow, October 16th. Speaking of quickly approaching dates, the National Portrait Gallery has a limited time exhibition “Factory of Femininity” open until October 19th, which explores how 20th century feminine ideals were formed in front of and behind the camera. Additionally, the Viktor Wynd museum is exploring “Dream Horror” in film via online lecture on the 19th, and the frightening “Parisian Theatre of Violence”, the Grand Guignol, in-person on the 27th, hosted by the fantastic Madeleine LeDespencer.

Film, Music, and TV. The 17th of October is set to be a day for the musical history books; Ashnikko is dropping her energetic album “Smoochies”, the Last Dinner Party is bringing us their highly anticipated sophomore album “From the Pyre”, and pop-rock fans have something to anticipate in Maggie Lindemann’s album “I Feel Everything”. To close off a month of amazing music, Florence and the Machine’s album “Everybody Scream” is dropping on Halloween, October 31st.

There is also plenty of monstrous fun to be had in the cinema this month, befitting of the season. Guillermo Del Toro’s electrifying new adaptation of “Frankenstein” will be available in theatres nation-wide starting on the 24th. To celebrate the 20-year anniversary of Tim Burton’s “the Corpse Bride” (2005), the film is back at a selection of cinemas for a limited time, including the 25th and 26th at Picturehouse. For a courtesan-adjacent pick, the BFI is screening the opulent “the House of Mirth” (2000) from October 25th to November 6th.

The Prince Charles Cinema also has an endless line-up of horror and terror classics selected for the rest of the month. Some choice picks include the chilling “Possession” (1981, playing 17th-31st), the witchy “Haxan” (1922) and the classic “Carrie” (1976) on the 20th, the original “Scream” (1996) on the 23rd and 27th, and an opportunity to channel your inner Sabrina Spellman with the pioneering “Night of the Living Dead” (1968) on the 26th.

In the Stars. Having just missed the Harvest moon on the 7th, the next lunar event to look forward to is the new moon on the 21st. Most importantly, Samhain is quickly approaching on October 31st. It is the time when the veil between our world and the spirit world is thinnest, the prologue to the darker parts of the year. Celebrate with bonfires, divination, and crisp red apples. And in case I don’t see you before then, happy Halloween!

Obsessive Tendencies: What I’ve Loved Lately

Koi Shoes, Gurren Strappy Platform Heels, [Burton-esque, reminiscent of Emma’s shoes in “Miss Peregrine’s Home for Peculiar Children”, 2016], £55

Jellycat, “Broox” Bat plushie, [In the midst of my extremely unexpected life changes, this little one has been my house hunting buddy], £30

NECA, Ultimate Nosferatu Black & White Action Figure, [My birthday gift to myself and celebrated party guest] £41.95

Fortnum & Mason, Alcohol-Free Sparkling Tea, [I crave to have a cellar filled with bottles of this delight, perfectly courtesan-esque for the sober-curious among us], £19.95

Replica, “Jazz Club” Eau de Toilette, [A smoky, mysterious scent reminiscent of whiskey and tobacco, but with a distinct floral kick], £62 for 30ml at Space NK

Dark in Love, “Doll” Coat, [I’m beyond obsessed with this coat; very feminine and dainty, doll-like], €76 at Fantasmagoria

“I had feared ghosts from the past, regrets, but there was only the heady perfume of it, not the pain. I lived the pain so deeply that it consumed itself and left nothing but a perfume.”

by Anaïs Nin, from “the Diary of Anaïs Nin, Volume VI, 1955-1966” (1976)

The house smells like smoke and violets; overwhelming, eye-watering, sweet. The third year anniversary of the White Lily Society (26th of October) is approaching swiftly! Something to savour amidst all the chaos. I wish I could write to you of a September that’s been kind, my dear, but I feel too tender to lie to you. Pray for the remainder of this October to treat me just a little bit better, is all I ask. Small requests for big results. Ritual is ever-increasing in importance; at night I leave the prime cuts off of my plate as little supplications to the universe. Tiny offerings to take care of the heavy sentimental bones weighing me down. Fret not, my dear, the dust is slowly settling into cardboard boxes and new steel keys and open endings. I will take the mouse inhabiting my kitchen with me in folded hands. Comfort can be stifling without us knowing of it. I think twenty four will be the year of blood, and devotion. Marbling and separating. Clotting. Let me pour champagne over top.

Until my next letter,

With love (and violence),

x Sabrina Angelina, the White Lily Society 𐔌՞. .՞𐦯

Currently reading: “Dracula” by Bram Stoker (still) // Most recent read: “To Wake the World” by Carys Maloney

White Lily Society links // Sabrina Angelina links

Come to me, sweet lamb. Wouldst thou like the taste of butter, a pretty dress? Wouldst thou like to learn about the Intersection of Love and Violence? Come, join us, and become a martyr of deliciousness.

📼 Song of the (past) month: Caribbean Blue - Enya

There is a long history of courtesans throughout the world, especially in Japan, Korea, and China, much before the practice ever caught on in Europe.

For ease of reading, all monetary amounts have been converted to their equivalents in today’s money unless noted otherwise.

The same can be said for girl’s working in a milliner’s shop, which Cora Pearl did for a while, as well as Lizzie Siddal, Pre-Raphaelite supermodel, who was neither a courtesan or prostitute, but as a model was regarded in similar fashion by polite society.

This is also when the famous tuberculosis chic look gets its moment, see newsletter 15.

Cora actually took her lingère to court once, insisting that she was being overcharged. The case was well reported on, to the disgust of news outlets sneering at the extravagance of material provided for Cora’s boudoir. Nevertheless, Cora won the case and a steep discount.

taken from Katie Hickman, “Courtesans: Money, Sex and Fame in the Nineteenth Century” (2003), p254

Many courtesans (and prostitutes) actually made quite “good” marriages for themselves, financially and socially, even if they weren’t accepted into upper society. That Elizabeth was somewhat accepted into the society of the king had more to do with her lovely personality than with her husband’s rank as a politician.

I had to include my invitation somehow, because I made it from scratch and enjoy pointing out all the references I hid in it :)

[Going top to bottom unless otherwise specified] The main image is a vintage postcard of Whitby Abbey, the ruins of which inspired Bram Stoker to write “Dracula” (1897). [Top left] includes an acquaintance card from Count Dracula himself, and a random news clipping about a vampire sighting. [Lower left] The scraps of a letter from Vlad the Impaler, and a Borrower’s Permit referencing a slew of H.P. Lovecraft stories and mythos, including Asenath Waite from “the Thing on the Doorstep” (1933).

[Right side] The telegraph card references Cainhurst Castle from “Bloodborne” (2015)— I had to find a way to explicitly include the theme for those who wouldn’t find all the references! Next is a tag referencing the “Healing Blood” from “Bloodborne” (2015) as well, with some references taken from in-game item descriptions and cutscenes (“Fear the old blood!”). The main letter is meant to resemble mourning stationery with its black edge, and references both “Nosferatu” (1922) in Orlok’s faint shadow on the paper, and the 2024 adaptation using the seal from the film and slightly reworked dialogue ˚ 𝜗𝜚˚⋆。☆