15. Martyrdom, oh My!

Leaving a beautiful corpse.

“September, the golden threshold between summer and winter.”

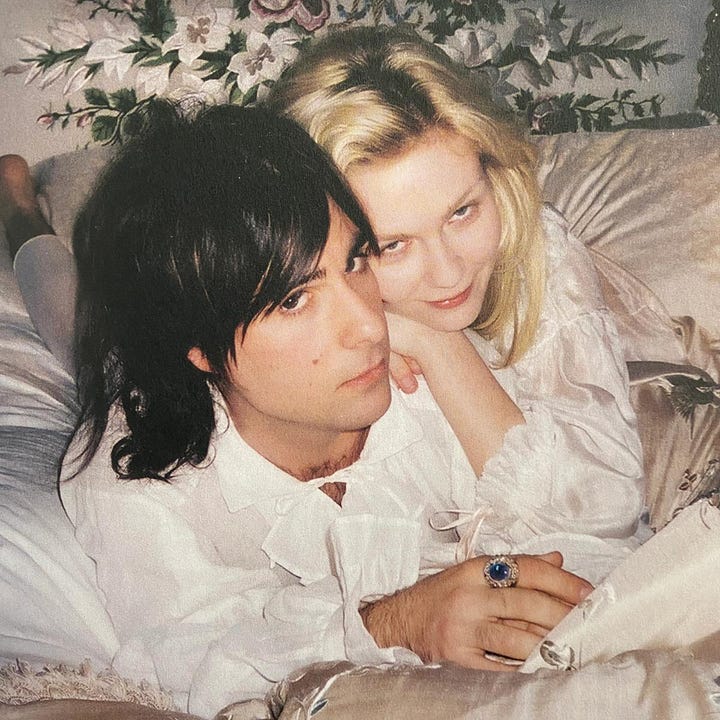

by Meeta Ahluwalia, unknown

This newsletter contains discussions of death and illness (especially corpses) that might be distressing to readers. Furthermore, there is a medical diagram of autopsy scars, and an image of a wax “anatomical Venus” model of the organs (mild gore warning) featured in Section “II.III An Anatomy of the Abject” that viewers might find disturbing. Readers sensitive to these sorts of images may want to skip the sections in question. Reader discretion is advised.

01/10/2024, London, UK

My dear,

If you have a vision of a dark forest, make sure you see me in it. Whether hidden behind a tree, partially obscured, or hiding out in plain sight. Dress me how you like. Red cloak or otherwise. Either way, I’ll be there, chasing the moths through the misty dark. Sleeping beauty resurrected, if only for one night. It’s a tale as old as time: the colder months give me a deep ache for fairytales, for folk music, for fragile magic— a cure for loneliness. Lovers like you and me, my dear, inevitably start believing in magic, in fate. It is written in our very nature. That nature is what I concern myself with.

When you walk the line between haunting and being haunted, always make sure to fill your thoughts with images of baptism, of soil. This is an essay that starts with the conclusion: you need not dream it to be true. Apologies for my cryptic verbiage, something skittered by in the dark, perceived weakness molten into armour, into strength. The reflection of a passing figure in the window glass. It scared me into jumbling up all my sentences, and now my alphabet is rearranged. Oh well.

Happy October, my dear. The phantoms and I wish you well.

This month’s newsletter started as a meditation on girlhood, and then it became about illness, about saints, about martyrdom and execution. It evaded my grasp masterfully like the bats I went to search for at the cemetery at dusk (and oh, did I see some bats!). Regardless, the angels that live in my laptop are whispering in my ear about the links between femininity and death, about the tragic woman archetype, about “Death and the Maiden” made flesh. So that is what I was made to write, and that is what you are getting. All writing is voyeurism, so peer in. You are more than welcome to.

As for news, I fear there isn’t anything of note. I’ve gotten so severely into the habit of just pouring the contents of my brain into this newsletter, that I rarely feel incentivised to do so in a shorter, more limited format. I enjoy the pure indulgence of typing here, of acting with a lack of constraints. That doesn’t mean that there isn’t anything coming, though. As submissions for our last limited-time prompt only just closed, you can be certain to see a few of them pop up on here in the following weeks. Supplementary reading for my darling. Oh, and I suppose there is one curious text already here, in the form of a poem of mine. It’s the first poem I ever got to perform in front of an audience, and for that it is very precious to me. Almost as precious as you are.

Now, enough sucking up (for now), let us march on.

I. Archive Updates

“I'm afraid to write. It's so dangerous. Anyone who’s tried, knows. The danger of stirring up hidden things— and the world is not on the surface, it’s hidden in its roots submerged in the depths of the sea. In order to write I must place myself in the void. In this void is where I exist intuitively. But it's a terribly dangerous void: it's where I wring out blood. I'm a writer who fears the snares of words: the words I say hide others— which? maybe I'll say them. Writing is a stone cast down a deep well.”

by Clarice Lispector, from “a Breath of Life” (1978)

Come one, come all! The traveling White Lily Society cabinet of curiosities has once more made its way down cobbled paths to stop right in front of you. See the lace curtains, the whimsical nature of the cart, the great arrangement of trinkets on display! All staple figurines lined up on the shelf alongside dolls and rosaries and porcelain swans: there is Ophelia, floating in her dim despair, and a woman, chained to her sickbed of all places, and Sofia Coppola’s films, with their glossy pink hyper-feminine consumerism, and underlaying discontent. If this was a chest of symbols, it would be rich. I invite you to peruse, to browse the wares on offer. Maybe one of them will strike your fancy, my dear?

“The Unified Theory of Ophelia: On Women, Writing, and Mental Illness” - link

More personal essay than hard-wrought academic paper, this work attempts to trace the author’s obsession with Ophelia through the ages, as well as the reasons why the character resonated so strongly with her. What she ends up settling on is that Ophelia specifically is a female character not strong because of her “madness”, but undeniable because of it. Her (perhaps) feigned madness makes her unable to be flinched away from, powerful even— something which we will return to embroider on later.

“To identify with Plath and Sexton was to take up the mantle of the mad female poet, madness being what they were chiefly remembered for. Hemingway’s suicide was just a footnote to his biography; Plath and Sexton’s suicides defined them. […] So I began to grapple with women’s “madness”, as both a personal and a literary conceit, trying to discover why it both allured and repelled me.”

“The Rest Cure: Repetition or Resolution of Victorian Women's Conflicts?” - link

The politics of women’s illness in the Victorian era is a subject we return to many times in this letter alone, but just in case you’re in need of a sampler before the main, this paper is a very effective look at the late 19th century’s “rest cure”: a treatment for women’s issues and ailments hinged on excessive bed rest and a complete relinquishing of control. The author looks, without judgement, on the reasons why such a treatment might have been efficient, as well as the symbolic nature of the acts within it, providing an accessible, and slightly infuriating look at the past, and one that I will continue to build on in my writing for this letter.

“Like his contemporaries, [the inventor of the ‘rest cure’] believed that women were fundamentally inferior to men and that their nervous systems were more irritable; both "facts" contributed to a woman's greater susceptibility to disease. And female irritability was firmly rooted in women's reproductive physiology and sexuality.”

“Sofia Coppola’s Melancholic Aesthetic: Vanishing Femininity in an Object-oriented World” - link

Any discussion of “girlhood” subculture and its associated ephemera would not be complete without a mention of any of Sofia Coppola’s films, most notoriously “the Virgin Suicides” (1999) and “Marie Antoinette” (2006). This paper does just that, looking at the burden of symbolism in Coppola’s heavily stylised cinematic worlds, while also acknowledging the white, straight, upper-class nature of the romanticised hyper-feminine sad girl archetype. It cleverly talks about femininity as distraction from melancholia, as well as commodity fetishism, and male fantasy. A captivating read on an increasingly enigmatic filmmaker’s work.

“There is a potent recognition in Coppola’s work, however, that the white, upwardly mobile woman of neoliberal capitalism – in her hyper-visibility – operates as a mere icon of politicised discourse. She is a constructed image, and as such is subject to the whims, fantasies and vilifications of the crowd that has placed her on a pedestal. No matter how hard the heroine tries, she is unable to craft a sense of self when she must also act as a projection of signs.”

II. Girlhood, martyrdom, real life DatM

“We felt the imprisonment of being a girl, the way it made your mind active and dreamy, and how you ended up knowing which colors went together.”

by Jeffrey Eugenides, from “the Virgin Suicides” (1999)

Before we start off, I would be remiss in not pointing out two major resources that were of use to me as I wrote this letter to you. The first was a live panel discussion I attended in late August organised by Isabella Greenwood called “The Sad-Girl Archetype in the Internet Age”. I suppose you could frame its role in this process as the tinder, the spark, the one thing that unraveled threads of inspiration within me. If you’re interested in what was discussed there, there are some brief audio highlights available here. Additionally, whereas I am only dipping my toes into girlhood for the time being, I would like to point you to lunulae, a friend’s substack and zine dedicated fully to themes of girlhood. If your appetite for these themes and aesthetics is as unending as language permits it, I’m certain you will find something on there to enjoy.

With that out of the way, let us dive in.

II.I The most poetic

“If pain can purify the heart, mine will be pure.” // “We knew, finally, that the girls were really women in disguise, that they understood love and even death, and that our job was merely to create the noise that seemed to fascinate them.”

by Mary Shelley, from “Mathilda” (1812) // by Jeffrey Eugenides, from “the Virgin Suicides” (1999)

Edgar Allan Poe famously wrote that “the death of a beautiful woman is, unquestionably, the most poetical topic in the world” (from “the Philosophy of Composition”, 1848). He argued that the most melancholy topics were the closest in alignment to beauty, and what ever could be more tragic than a waste of life, of youth, of beauty, as in the death of a beautiful woman? Hypothetical question, of course. Text does not usually allow for reply, my dear. Undoubtedly, Poe was onto something, not in the supposed truth of his statement, but in the mere popularity of the iconography it prescribes. One needs only open their eyes to see it: my precious “Death and the Maiden” goes beyond it’s 1:1 tropes, absolving one end into metaphor and bleeding into the figurative realm, into art, into real life. Female suffering is consumptive, is gorging itself, feeding desperately on the remnants. It is stuffed down our throats for breakfast, lunch, and dinner. It is inescapable tragedy, wound up, it seems, in the very fabric of what it means to be woman, girl, other. Or rather, as Elisabeth Bronfen writes in her book on death, femininity and the aesthetic (1992): “woman–death–womb–tomb” (p86).

Dead girls are everywhere, even where women take up the pen. Classics like “Frankenstein” (1818) revolve around women bearing the grunt of the consequences for male bravado, so that their lifeless bodies can be found, and mourned over to strengthen the [male] protagonist, the hero. Think of the movie tropes you know: the montage of the dead protagonist’s wife, meant to assert her status as a symbol of purity to be avenged, the “freezer bride”, whose suffering and death incentivise those around her, strengthen their resolve. The disposable woman, as prop, as story beat, as disappearing act. Now you see me, now you don’t. Women don’t [often] get to play god, they don’t get to avenge, they don’t get to hunt down justice. They get to be Mother Nature, as in they get to give, not take. The saint, the virgin, the whore. Mother, maiden, crone. The woman as pitcher to be poured into another’s cup, the girl as a symbol of all to come. All the pieces to be auctioned off and taken from her.

It is tragic then, following that reasoning, when a woman dies, for her role in the story is ever cut-short, ever melancholic. She was not yet done giving to us. Tragic at least for as long as you can forget that women, too, are intimately familiar with death, that they are not sheltered from sin. Even the fact that their death is often a catalyst for the unwinding of a tale seems to suggest a brush-in with darkness, off-screen but undeniably there. For a woman to be a thing as desirable as a corpse, she of course has to die first, has to be consumed by the antithesis of the light she narratively and symbolically represents. All to be the centre focus of a tale ultimately not her own, how lucky!

"That's the beauty / of a dead girl. Even a plain one / who feels worthless / as a clod of dirt, broken / [...] / can be made whole, redeemed / by what she finally can't help being, / the center of attention, the special, / desirable, dead, dead girl."

by Kim Addonizio, from “Dead Girls” (collected in “What is this thing called love”, 2004)

II.II Sickbed Seduction

“Sometimes I think illness sits inside every woman, waiting for the right moment to bloom. I have known so many sick women all my life. Women with chronic pain, with ever-gestating diseases. Women with conditions. Men, sure, they have bone snaps, they have backaches, they have a surgery or two, yank out a tonsil, insert a shiny plastic hip. Women get consumed.”

by Gillian Flynn, from “Sharp Objects” (2006)

That femininity is innately linked with death is not a new idea, by any means. If we examine our common language, “womb” and “tomb” are only one letter removed. “Mortal existence is a form of decay” (Elisabeth Bronfen, “Over Her Dead Body: Death, Femininity, and the Aesthetic”, 1992, p71), and so what (or who) gives life also inevitably condemns one to death. The two are inextricably intertwined, you cannot have one without the other. To be born is to die. Supplementing this link, there is the ideal of women as sickly, dainty, fragile, which is not only patriarchal in construction, but has firm roots in historical notions of what it means to be a woman. The term “hysteria” came from the Greek word for “womb” (“hystera / ὑστέρα”). It was believed that the womb would actually travel through the body and cause madness. Ancient Egyptians believed that a woman’s depression and anxiety was caused by their uterus. These ailments were not just regular ailments, they were specifically thought of as feminine ailments. The sickness came as a package deal with the womb, sorry not sorry. Better luck next time!

But it’s not just mental illness that was considered “feminine”. In the 17th and 18th century, during the rise of consumption (now known as tuberculosis), the disease became a sort of fashionable status symbol. For context’s sake, the spread of this disease cannot be understated in its scale: it is estimated that 1 in 7 adults died of tuberculosis in London, and that it killed roughly a quarter of the adult population throughout Europe in the 19th century alone. Its symptoms were not pretty. Dubbed “the White plague”, the disease slowly killed, draining and consuming the life of its victims. However, in the face of such a gruesome illness, the Victorians found a rather… odd sense of beauty.

Consumption was thought of as “feminine”, because of the notion that it led to a “beautiful”, serene death. A myriad of symptoms of the disease were all thought to be highly desirable: a pale, nearly-translucent complexion, visible veins, pink lips, enlarged pupils, slender form, blushed cheeks, heightened sensitivity— all translated to a certain delicate frailty that the Victorians thought impossibly graceful, and Romantic. Sentimentalism made consumption beautiful. At least, if you left out all the blood being coughed up from the patient’s lungs literally dissolving. “In the last stage of a consumption, a lady may exhibit the roses and lilies of youth and health, and be admired for her complexion— the day she is to be buried” (Carolyn A. Day, “Consumptive Chic: a History of Beauty, Fashion, and Disease”, 2017, p84). Of course, as the masses subscribed to such consumptive beauty standards, they began to emulate them using cosmetics, including white face paints containing lead. But alas, nothing artificial could ever compare to the real thing.

Being an invalid was desirable, not just because of the supposed fashionable beauty it lent to the sufferer, but because it allowed women in particular to be unashamed in their request to receive care instead of just giving it: “Women with enough money and time could learn to enjoy illness. It was a way of imposing themselves on their household, without breaching their role as a duty-loving, self-denying angel in the house. It was, in short, a way of finding time and space for themselves in a society that did not allow them to want either things openly.” (Judith Flanders, “Inside the Victorian Home”, 2004, p358). Of course, the politics of disease were entwined with a generous serving of classism as well. The ailments of the upper class were often framed as genetic or inevitable, while the illness of the working class was always a result of bad moral standing or personal choice.

There was social currency to be gained for those who could afford to be sick, and “women were possessive about their illnesses, which were often prefixed with the pronoun ‘my’, as in ‘my headaches’: it was part of their public persona, and possibly gave them status” (“Inside the Victorian Home”, p359). To be ill as a woman was not just to be ill, it was to be ill because of their gender, their femininity. “Women were subject to ‘feminine disorders’. Their femaleness dominated their lives, and could not be controlled. […] A woman was, in terms of both her health, and for psychological state, her ovaries.” (p357). In embracing this notion, to get a break from the numerous and contradictory pressures piled upon them, women of the time were also reinforcing the vicious cycle of what it meant to be a woman, and what was expected of them: to succumb to the ailments expected of the “fairer sex”.

II.III An Anatomy of the Abject

“[…] the multiply coded feminine body, in its triple function as site of an original, prenatal dwelling place, as site of fantasies of desire and otherness, and as site of an anticipated final resting place.”

By Elisabeth Bronfen, from “Over Her Dead Body: Death, Femininity, and the Aesthetic” (1992), p72

The woman struck dead as a symbol is uniquely concerned with the concept of wastage. A corpse itself, regardless of gender, serves this semiotic purpose. Per Kristeva: “[…] the corpse [is] the most sickening of wastes” (from “Powers of Horror: an Essay on Abjection”, 1980). The added (and implied) beauty of the dead woman or girl in particular is then a wastage of a common good, an asset to the world at large. The aesthetiziced death of the woman is rarely thought about in personal terms, but rather objectified as a loss for the collective, as if the real topic of mourning is a world tinted just one shade bleaker. Where one might imagine a direct relevance to the family in relation to the death of a man, the death of a woman is secured to dozens of tiny strings, which are in turn connected to the world around her. This is substituted by the viewer’s imagination of the scene, the woman alive, one in which the woman is never alone, but seen in relation to others, watched through someone else’s eyes.

“For each man who regards it with awe, the corpse is the image of his own destiny. It bears witness to a violence which destroys not one man alone but all men in the end. The taboo which lays hold on the others at the sight of a corpse is the distance they put between themselves and violence, by which they cut themselves off from violence”

by Georges Bataille, from “Eroticism” / “Erotism: Death and Sensuality” (1957), p44

When Kristeva wrote her landmark essay “Powers of Horror: an Essay on Abjection” (1980), she defined the “the abject” as a place where meaning collapses, and horror emerges as a result. She describes the corpse as “the utmost of abjection. It is death infecting life. Abject. It is something rejected from which one does not part, from which one does not protect oneself as from an object. Imaginary uncanniness and real threat, it beckons to us and ends up engulfing us.” But the corpse of a beautiful woman is not a place where meaning goes to die [within art]. Rather, she is pregnant with symbolism and meaning. She incarnates dual concepts of both purity and death, youth and mortality, beauty and waste. And women themselves are semiotically seen in such blurred, contradictory terms: “Woman incarnate no stable concepts. Because she semantically encoded as good and evil, as the possibility of wholeness and the frustration of the dream, the connection to the infinite beyond and a measure of human finity, the one stability to be found in myths of femininity is in fact, ambivalence” (Elisabeth Bronfen, “Over Her Dead Body: Death, Femininity, and the Aesthetic”, 1992, p.66).

Though the subject of death might strike one as vulgar, morbid, something to be winced away from, projecting this death onto a beautiful woman makes it more palatable for the viewer, the survivor. Where otherwise a corpse might be reaffirming, warning of the viewer’s mortality, the female corpse instead instills a sort of “survivor’s pride”, a wall between the dead and the living. Not dying and dead, but living and dead, black and white. Of course this juxtaposition necessitates that the corpse in question is without visible decay, young and beautiful forever. The most poetical topic.

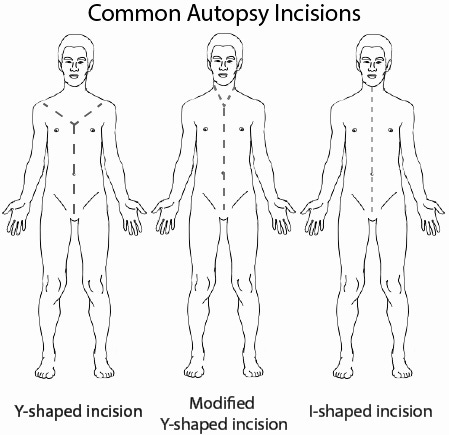

Which brings us to the myriad of “anatomical Venuses” from the 19th century: wax models of beautiful women, interchangeably asleep or dead, that can be taken apart to peer into their inner anatomy, the place where secrets are nested between intestines. Anatomical wax models of the time were produced “in an attempt to distance the study of anatomy from the contemplation of death and bloody internal organs”. (Joanna Ebenstein, “the Anatomical Venus”, 2016, p28). So then why did they specifically become beautiful women? The de facto corpse might not be stereotypically thought off as female, but autopsy incisions remain ever-pointed at the womb— a y-shaped incision running down the collar blades, the abdomen, and ending at the pelvis. Yet there are no scars on the anatomical Venus. She lies undisturbed, except for the plates that can take her apart like a morbid jigsaw puzzle.

There is no doubt that the anatomical Venus is both art object and educational marvel at once, a work trivialising the gruesome nature of the pursuit of taking something apart, dissecting it. Some of them feature phantom hands, stretching the Venus open or simply touching them. Beyond the Venuses, smaller female anatomical models of the sort sometimes came with novelty foetuses attached by a little string. These models were less accurate, meant more for sentiment than precise education, and perhaps even an odd sense of entertainment. One must wonder: is it less gruesome if the woman does not feel it? Is it not still a power exchange, to peer into someone’s insides, to hold the metaphorical blade? Can this simulation of playing God really be seen as purely educational?

There is an obsession with the beautiful corpse that cannot be shaken off. Beyond the aforementioned anatomical Venuses, there are more examples of IRL “Death and the Maiden”, some of which I’ve briefly discussed before. This includes the [in]famous photograph of Evelyn McHale after she jumped off the Empire State Building, to her unfortunate death. As she landed on top of a parked car, looking restful rather than dead, ankles tied together to protect her modesty, the curved metal of the car looking as soft as silk, a nearby photographer snapped a picture, resulting in an image that is often referred to as “the most beautiful suicide”. Or there is “L’inconnue de la Seine”, the story of a young woman who drowned in Paris in the 1880s, whose beauty so enamoured the coroner handling her remains that he made a death mask of them, later going on to become the standard mould for CPR dolls: “the most kissed face of all time”.

But think also of a cultural fascination with dead celebrities, with images of Marilyn Monroe, resting serenely in bed upon first glance, but actually having passed away. It is often said that the best things artists can do for the value of their art (both cultural and monetarily) is to die, and the same extends to icons of the culture. The faces that in themselves become caricatures, become idols, become cheap and easy Halloween costumes are always married to an ironic tragedy. Their lives taken early, or tinted with melancholy, their shining star careers abruptly interrupted. Not to even mention the can of worms that is the modern cultural hyperfixation on true crime obsession, and the ways it disproportionally tells stories of gruesome acts befalling women.

In a world where beauty is in most ways the supreme currency, but visible pursuit of it is thought of as tacky, or simply vain, egocentric, vanity is both a capital sin and a cultural point of interest. This is especially true for centuries past where “beauty was seen as the outward expression of a virtuous character but cultivating personal beauty was condemned as hollow vanity” (Wellcome Collection, “the Cult of Beauty” exhibition text, 2024). Performance is always lauded as morally bad, artificiality as sin. Unless it performance that plays to the audience’s appetites: the unaware beauty, the unwell woman, the placated and pretty victim. The beautiful corpse on the table, helpless against the anatomist’s blade. A spectacle of obedience, but never disobedience. And yet, beauty is only fleeting. Its “dying” is inevitable. The [male] fantasy of the beautiful female corpse is in its preservation, in the fact that even though the house (Death) always wins, there is still a minor personal victory to be had, in the beauty of one’s death, the ornament of one’s remains.

“The Rites of Beauty are intended to make women archaically morbid. Five hundred years ago, men thought about their lives in relation to death as women today are asked to imagine the life span of beauty: Surrounded by sudden inexplicable deaths, medieval Christianity made the worshiper’s constant awareness of mortality a lifetime obsession”

by Naomi Wolf, from “the Beauty Myth” (1990), p88

II.IV Martyrdom, piety, and voyeurism

“Who were the female saints, I say, and how did they manage to fill their beds with God? How can any woman from this empty world construct communication with heaven?”

by Elizabeth Smart, from “By Grand Central Station I Sat Down and Wept” (1945)

We have seen that hysteria and [mental] illness could be used throughout history for women to gain a voice in society, a little bit of wiggle room within a tight gilded cage. Perhaps this is also why the girls of the 21st century gravitate to such terms, to such images, to such tropes.

That these symbols of martyrdom function as idols for women is not odd. Consider the ironic embrace of women’s disease, with jests about being sent to the seaside for one’s health, being the lamb of God (Agnus Dei), or even needing a lobotomy. It’s a rite of passage for girls to claim their own tragic nature, the one seemingly inherent, natural to the feminine. One complete with long floating gowns, hair draped over chairs and sofas, billowing skirts. Drowning in fabric typically, but always looking as if she could simply… float away. Disappear, fade. And that is often what the stories have her do. If it not sickness, it is heartbreak, or it is tragedy.

The sickly woman, immortalised in both youth and beauty is everything women are told to be. Ornamental, not bothersome, easily supplicated. Dying but still beautiful, a male fantasy. And it is easier for women and girls to shift into the caricature of these roles because they are so little explicit about the suffering involved in them beyond aesthetic terms. Even modern notions of what it means to be a woman of [mental] illness lean this way: terms like “bed rotting” which were meant to shed light on the neglectful side effects of mental health problems like depression are now glossy and commercialised, DOA the second companies started using it to advertise our own ironic embrace of the culture back to us. See also: “girl dinner”, “delusional”, etc etc. The list is practically endless.

But one thing that is important to think about, and to consider in our ongoing dialogue of these tropes is that for some women it is indeed comfortable to slip into caricature. After all, that is what the bars of the cage are made of: symbolism, tropes, motifs, themes, stock characters. Like the aforementioned ambivalence of women as symbols themselves, the tropes surrounding them are contradictory, equally oppressive and liberating at the same time.

Ophelia, Shakespeare’s “mad woman” from “Hamlet” (1600-1602), for example, can not be squarely categorised within the tropes of female illness. Rather, she weaponises it. “Ophelia uses the outward forms of beauty and femininity to articulate her devastating grief, and in doing so, transforms herself from an object that is pleasant to look upon, into a person with a story that condemns and reproaches” (Archive Source 1). She is both male fantasy (beautiful, feminine), and female power fantasy (unable to be looked away from or ignored), thus comes the interesting duality of her character, and the ways in which the genders interact with her: “Women seemed to invoke her like a patron saint; men seemed mostly interested in fetishizing her flowery, waterlogged corpse” (Archive Source 1).

That looking, that watching is a cornerstone here. I’ve written before about the eeriness inherent in the female experience, that uncanny feeling of always being watched. Margaret Atwood described it best when she wrote: “You are a woman with a man inside watching a woman. You are your own voyeur” (“The Robber Bride”, 1993). The female experience is uniquely centred in the third person. Decades of the male gaze in cinema have taught us to look at woman through the lens of a man, the same way as is done on-screen. Hell, there have been studies that show that women as well as men frequently see women as a collection of individual parts and men as whole beings, the same way voyeuristic camera shots of women in film usually focus on specific parts picked to appeal to the [often] male audience.

Even if you are doing everything “right”, you are still being looked at. There is no escaping a gaze that comes from inside of you, as well as from outside. For medieval female saints, practically the height of piety, their devotion and virtue came with a free serving of voyeurism, or rather, scopophobia: the fear of being looked at. Beyond the intrusive nature God seemed to effect onto their lives, manifesting as voices and invisible eyes, their afterlives were represented as rife spectacle for [male] viewers in painting, while the more detailed descriptions of their lives were favoured by female audiences. Even then, the focus was overwhelmingly on their appearances. Medieval sentiments believed that the beauty of a person was reflective of their inner beauty, their soul, but perceived “vanity” was still all-too eagerly called out in women: “Reformers complained that the statues of female Saints and churches were too beautiful and too richly, dressed, more like courtesans than holy women” (Erika Langmuir, “A Closer Look: Saints”, 2009, p54) Which leads us to “virtue”, and by extension, execution.

II.V Execution

“We are spared the martyrdom and shown the miracle”

by Erika Langmuir, from “A Closer Look: Saints” (2009), p56

The very real history of gender and execution is also at play when we talk about the effects patriarchal views of women had on their lives. “Modesty” played a big part in how women were punished, and subsequently executed for their crimes. For example, it was thought better for women to be stoned to death or buried alive, rather than be hanged, for when they swung from the gallows, their skirts might rise up and expose them. Therefore, if they were hanged, their skirts would be tied around their ankles with rope. One further restriction for the lot. Live burial as punishment for women in particular, harks back to the Romans, who typically buried alive vestal virgins (ie. servants of the goddess Vesta) who broke their vows of chastity. And this notion then translated into medieval times, because, as opposed to burning or hanging women, which offered an “indecent” spectacle of suffering, the act of burying a woman alive preserved her modesty. Yet hanging was still considered a feminine punishment, and the principle of modesty was often juxtaposed with the principle of spectacle: to be hanged or not, to have the face covered or not, all such things went back-and-forth endlessly. Whether a woman deserved to die with their honour, and their modesty, intact depended almost wholly on the class of the victim in question.

Ideas of modesty, virtue, and decency were vague at best. There was a general sentiment that women were inherently innocent, tender creatures, in need of male protection, but “the medieval concept of modesty [began] rather to resemble Kant’s notion of the sublime” in its vagueness (Camille Naish, “Death Comes to the Maiden: Sex and Execution 1431-1933”, 1991, p9). Modesty’s colours shifted depending on who you asked, what class they were from, what country they were in. Vague ideas of chivalry could contort any act into one really meant to preserve a woman’s honour, no matter how gruesome.

It is ironic then that women at the same time as being innocent, pure, and in need of protection, were hunted and persecuted for their ability to upset the status quo, mainly through “witchcraft”. Women were these pure beings, made of light, but they were also suited for witchcraft, which the Christian church believed “[came] from carnal lust, which is in women insatiable” (Camille Naish, “Death Comes to the Maiden: Sex and Execution 1431-1933”, 1991, p26). I suppose it does not matter. This is a pick your own adventure story, where either end results in female suffering: the illusion of free choice. Behind this door is the gallows, behind this one the sword.

“the veneration in which female chastity was held, […] One might describe chastity as the bright side of a female coin whose dark reverse was a Satanic predisposition to lewdness.”

by Camille Naish, from “Death Comes to the Maiden: Sex and Execution 1431-1933”, (1991), p40

A friend of mine once alerted me to the true definition of “virtuous”, which is, to do what is in line with one’s morals. This means that to be virtuous means first deciding upon a virtue to follow. Even if your chosen virtue is misguided, then acting upon it is still “virtuous”, to you. It is in line with your morals, however crooked. Certainly this played a part in historical condemnations of women, minorities, criminals and the like. It is [mostly] unthinkable now to us to justify any actions so brutal or cruel, but then again, the idea of virtue has been transformed into ideas of personal, individual morality. The more we emphasised that each should build their own worldview from scratch, the further we stepped from history. We are quite literally near-incapable of understanding the past in direct translation. Nevertheless, we have taken a stab at it today, and I’m sure many others will in the future.

It certainly wasn’t for lack of trying.

III. What to watch this October: a Halloween movie list

“Horror stories upset all the right people. People who can’t ambiguity, people who can’t handle violence or eroticism, people who think of the world in these very clear-cut terms— Horror designed to make you incredibly uncomfortable”

by Carmen Maria Machado, from “Queer for Fear: A History of Queer Horror” (2022)

With the spooky season dawning upon us, it is no doubt to me that a great many of you will now start to seek out your frights, your scares, your things that go bump in the night. As the darkness approaches, there awakens an insatiable hunger in all of us to be haunted. Most preferably in the comfort of our own homes, with a few snacks, and a warm blanket, of course. A controlled environment is best.

With that in mind, I have compiled a list of seven films in this letter just for that very purpose, ranging from silly spooky to subtly scary, but none too intense on frights or gore (if you ask me). What makes good October viewing is indeed all about atmosphere to me, and that is the primary thing you will find within the films listed: they’re practically oozing atmosphere in every frame. Still, enter at your own risk. Your mileage may vary, and you have been warned.

“Scream” (1996)

It truly wouldn’t be Halloween without a slasher movie, and it would be downright criminal for me to exclude the classics from this list, so voila. The original “Scream” is probably as classic as it gets, my dear. It’s truly curious how well the signature “Scream” series’ mix of meta-humour and genuine slasher thrills still holds up, even today, and what better way to trace its legacy than to go all the way back to its source? Whether you’ve seen it before or not, this is essential Halloween viewing. Simple as that.

“No, please don't kill me, Mr. Ghostface, I wanna be in the sequel!”

“Crimson Peak” (2015)

Guillermo Del Toro’s 2015 film “Crimson Peak” is a storytelling masterpiece of style, subtlety, and the nuances of the Gothic Romance genre. To call this a horror film would be uniquely misguided— a handful of ghosts and an array of blood-curdling frights does not a horror film make. Rather, the tender layers of dread that make up this film create an atmosphere of terror and intrigue, with some supplemental mystery on the side. It includes candle-lit exploration, flowy white nightgowns, and a Gothic mansion to die for, so for style alone I would already highly recommend this film. Add in the story, the attention to detail, and oh, you’ve got my heart beating a bit quicker. With love, that is, not terror.

“But the horror... The horror was for love. The things we do for love like this are ugly, mad, full of sweat and regret. This love burns you and maims you and twists you inside out. It is a monstrous love and it makes monsters of us all.”

“Jennifer’s Body” (2009)

It took quite a long time for people to understand “Jennifer’s Body”. Grossly mis-marketed at the time, the themes of the monstrous feminine, female friendships, and the obvious queer overtones (not undertones by any stretch of the imagination) were not easily digested by the public of the 2010’s. Which is why I’m glad this film finally found its audience, because I am firmly in it. It’s quotable, it’s fun, it’s campy— although you emetophobes might want to skip one extended scene in particular. Either way, this is the one to watch at a sleepover for a less straight-up terrifying option.

“Hell is a teenage girl.”

“The Torture Chamber of Dr. Sadism” (1967)

The older a film gets, the less likely it is to scare us. This is especially true for this 1967 film, known under a great variety of names including “Blood of the Virgins”, “Omen of the Devil”, and “Pendulum”. This is a properly cheesy film, filled with horrendously absurd genre contrivances like swinging pendulums, strait-laced Dracula references, virgin sacrifices, Gothic inspired familiar relationships, and some gloriously low budget set design. Not scary, but rather… spooky. The kind that is curiously purple/orange/electric-green coloured and comes with connotations of classic Halloween monsters in cartoon form. Somebody play “the Monster Mash” by Bobby Pickett, please.

“Time makes no difference to the dead.”

“Ginger Snaps” (2001)

Truth be told I have not stopped thinking about this film since I first watched it this July. “Ginger Snaps” is a werewolf story with a uniquely gruesome twist: it’s really a film about the body horror of being a girl, about menstruation and moon cycles. But don’t let that turn you off. While it is not subtle about its themes in the slightest, it also provides a gorgeous [s]platter of spooky and morbid visuals, and the occasional fright in the third act. It simply ticks all the boxes.

“I get this ache… At first, I thought it was for sex, but it’s to tear everything to fucking pieces”

“Sleepy Hollow” (1999)

However you go about it, “Sleepy Hollow” is a film sparkling with unadulterated care, with ambiance, and detail, as if the cold wind could claw its way out of your television set and into your frightful bones. For that alone, I adore it. This is a classic Tim Burton movie, with a New England folktale setting, complete with witches and storms and anatomists. While the story might be a bit rickety or basic at times, my supreme enjoyment of it came mainly from the ambiance and the gorgeous visuals. Long story short: I want every film to feel like this one.

“The Horseman comes, and tonight he comes for you.”

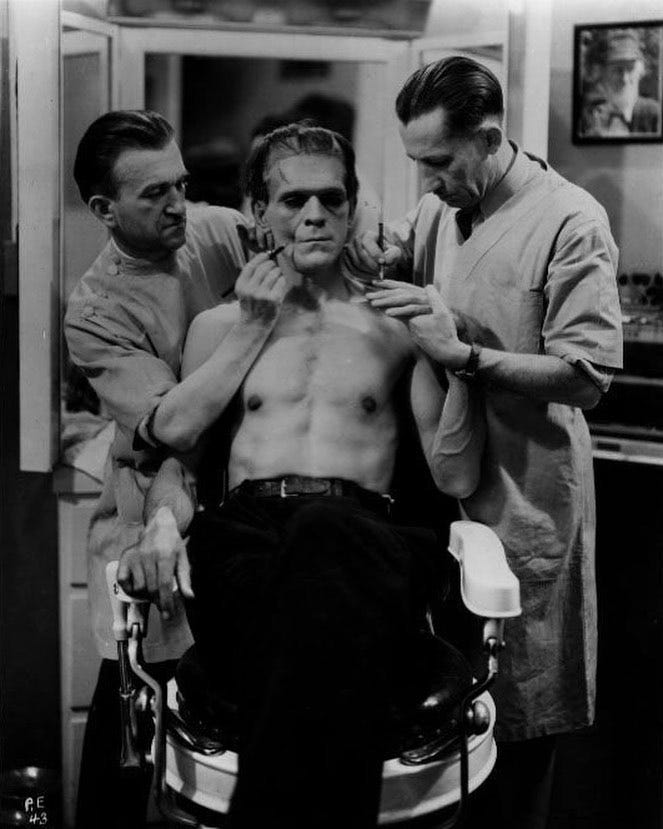

“Frankenstein” (1931)

Not so much scary as it is atmospheric, I picked this classic universal horror monster film for last because of the vibes. This is a stunning film, and surprisingly digestible in length. While it is without a doubt, a very unfaithful adaptation of the source material, this film has merit for just how salient it is. So much of our modern lexicon surrounding Frankenstein came from this film alone (“It’s alive!!”), and from Boris Karloff’s supreme performance. The warning up-front is a nice touch too, reminding you of just how frightful such a tale must have been when the film originally aired.

“We're about to unfold the story of Frankenstein, a man of science who sought to create a man after his own image without reckoning upon God. It is one of the strangest tales ever told. It deals with the two great mysteries of creation: life and death. I think it will thrill you. It may shock you. It might even horrify you.”

“Everything I know, I know because of love.”

by Leo Tolstoy, from “War and Peace” (1869)

The hour of the witch is upon us now, golden moon bright above. If you find the fog run into your brain, do not be surprised. It is the colder months that tend to drain. So focus on nursing yourself with devout piety. Remember that sometimes the spoils are only the second best thing. Do not misspeak in your prayers, be careful what you wish for, do not invite the uninvited into your sanctuary. Spirits are rampant at this hour.

As it was my birthday last my months, the friends present at my dinner party went around telling me what they most appreciated about me this year. They mentioned my passion for my interests, my manner of finding beauty wherever, but also that they felt safe and comfortable speaking to me about anything, now matter how controversial or personal, and I wish to cultivate and grow that, watch it blossom into harvest. I have been practicing this art of unfolding for a few years now, and it is something I don’t ever presume to lose interest or enjoyment in. This October, I would love for you to join me in that, my dear, and to take a few steps closer to who you would eventually see yourself being. The White Lily Society, too, has a birthday coming up: it turns three this month, on the 26th. But for now…

Affirmations for October (repeat after me) 1. I will not be confined to sorrows 2. If I am forsaken, it is only so that I can find my own way 3. It is my pleasure to haunt the narrative of my own life, always

Until my next letter,

x Sabrina Angelina, the White Lily Society

Currently reading: “Over her dead body: death, femininity, and the aesthetic” by Elisabeth Bronfen // Most recent read: “The Doll’s Alphabet” by Camilla Grudova

White Lily Society links // Sabrina Angelina links

*Cough, cough* Oh, please grant a dying woman your favour and consider subscribing to her humble newsletter. What’s that? What am I dying of? Life, of course, my dear! We all must go eventually. But let us return to the question at hand: subscribe now, and you get every new letter hand-delivered by crow to your inbox! Become a martyr of deliciousness, and subscribe. Much better than being a regular martyr, let me tell you! Just take my humble word for it…

Incredible commentary on how intrinsically death and womanhood are linked. It's so sad to me how womanhood is terribly villainized in nearly every aspect but in death. The corpse is truly ideal as it cannot talk, cannot want, cannot desire. It serves as a statue of flesh, and even then the beauty of a dead woman is limited. She is not beautiful if she died old, she is not beautiful once her skin bloats and maggots bore into her. She's only beautiful for a short window, and even then is not awake to enjoy it. I feel like it harkens back to girlhood, and how that time for many is one of the only moments a girl can be effortlessly beautiful in her youth and innocence. The irony is the fact that one, you are never aware of yourself when you are most beautiful, and two, the beauty lies in the perceived weakness and purity of the woman. Something, something, something, there's a poem there somewhere :)