22. Heraldry

The pen is mightier than the sword, and much more addictive.

“But it was a May afternoon and with its perfume the fresh air was an open flower. So she thought it was marvelous and strange to be walking the streets—with the wind ruffling her hair. She couldn’t remember when she’d last been alone, with just herself.”

by Clarice Lispector, from “Beauty and the Beast or a Wound too Great” (1991)

TW. There is a set of GIFs in the outro of this newsletter from the TV show “Yellowjackets” (2021-) that show fake blood. You have been warned!

01/05/2025, London, UK

My dear,

The ice is melting over innocence; the horns are sounding into the jubilant distance. I have been mesmerised by Venus, its movements within me, the lunar glow of it, and all the different facets of the planet— how it is the most dominant force in my birth chart by far. Ten aspects of it; seven major and three minor. As a curator of the beautiful and bizarre, I really shouldn’t be surprised. I like what is pretty to look at, but morally often deplorable. What else is new? This is the time to check the pulse on tenderness, to make sure its ways are still alive inside of you. It does take effort not to let the sweetness fade.

April made no fool of me. My house was a boarding house for all the most beloved of souls, my dearest friends. And there’s divination in the air, the prophetesses are calling out, all the darling symbols are open to interpretation. Quick, get out your dream dictionary! My life lately has been absolutely plied and stuffed with dreams, but one could attribute that to the nauseating heat taking root deep inside of me. I was never one to like the warmer months, always wanted to stay inside and keep cover in the shade. At one point my young eyes practically adapted to be most maladjusted to the light of day. All of these things are loosely related, my dear. The spider’s web enshrining them is fragile, it sways in the wind, but it is there nonetheless. Arachnomancy to occupy me while the sun sets and the air becomes inhabitable again.

This month’s newsletter is a hard sell, perhaps. The Gothic literary tradition and the luxury fashion business model on first glance have very little in common… or do they? What if I told you that they are, in fact, largely related. Siblings, maybe, or cousins. Either way, they meet eyes at big family events; dinner parties, weddings, and funerals. They keep in touch from time to time despite having taken on different surnames. Here, allow me to unroll the family tree that connects them.

Careful, the scroll is fragile to the touch.

I. Archive Sources

“My heart is like a haunted house” // “She herself is a haunted house. She does not possess herself; her ancestors sometimes come and peer out of the windows of her eyes and that is very frightening.”

by Florence + the Machine, from her song “Haunted House” (2019) // by Angela Carter, from “the Lady of the House of Love” (collected in “the Bloody Chamber”, 1979)

A house need only spirit to be haunted— pun intended, my dear. Pray, forgive my occasionally gauche tastes, I fear they’re a side effect of a prolonged interest in Gothicism, evident in this very letter. You see, as I pondered the Gothic bones of the luxury fashion “houses” this past month, I turned to heritage, to legacy, and eventually to the classic haunted house. This is a logical progression of affiliations: the deeper the legacy, the thornier the heritage, the stronger the haunting turns out. Whether ‘tis a matter of the supernatural, or just of human depravement, the house itself is a breeding ground for the kind of corruption that can only originate in a family. So in order to analyse how the luxury fashion “house” has become haunted, one must first build the foundation for it. The collected readings here serve to do just that; they are the stepping stones to the larger connections later in this text.

Observe them with care and curiosity.

“Haunted Houses” - link

A relatively short primer on the idea of Gothic’s beloved haunted house to warm up with before the more heavy fare. There is talk of Poe, of course, as well as famous ghost stories like “the Turn of the Screw” (1898), and “the Haunting of Hill House” (1959). Most interestingly, this paper briefly touches on the idea of the Gothic tradition with all its romantic sensibilities and “irrational” turns as a representation of a more emotionally-lead (stereotypically “feminine”) attitude, juxtaposed against the rigid and cold (stereotypically “male”) world of reason. The haunted house, then, could serve as a representation of age-old patriarchy, frequently invaded by the female heroine, and succumbing to the progressiveness of time moving on.

“The unhomely home therefore houses the Freudian family with all its secrets, forbidden desires and murderous impulses. This family then becomes associated with and represented by the house itself – the home – the building in which the family dwells. To a certain extent, the home even is the family.”

““Better for Haunts”: Victorian Houses and the Modern Imagination” - link

Investigating the history of the traditional “haunted house” aesthetic in great detail, this paper traces its origins throughout American art, literature, and eventually, pop culture ubiquity. It brings up all manner of interesting details in its twenty pages, from the idea of the Victorian parlour as closely related to a funeral home in atmosphere (it was after all, the room in which the recently deceased would be laid out pre-funeral), to the idea of the Victorian era as being unhygienic, barbarous, or quote “homey and horrible”.

“Like a body, the Victorian house enclosed a spirit within its shell. Exterior and interior were coextensive; the facade with its turrets, mansard or steeply gabled roof, irregular angles, and jigsaw scrollwork promised inner spaces equally eccentric and complex, equally disconcerting. Indeed, in contemporary opinion, Victorian houses were made to be haunted.”

“The Missing Mother: The Meanings of Maternal Absence in the Gothic Mode” - link

Many of the stereotypical plot contrivances of the Gothic tradition can be attributed to the historical context it existed within. Its marriage-drama, for example, is partially explained by the legal idea of “coverture”, or the woman belonging to her husband, undergoing a civil death upon exchanging her vows. Likewise, the common inheritance-drama exists because of “primogeniture” legally restricting the passing down of estate and wealth to male heirs only. Thus, the Gothic woman legally doesn’t exist; she is owned and bypassed, side-stepped in the narrative she either haunts, inhabits, or runs from. That the maternal presence is often missing from these stories is in fact a fictionally internalised facet of this real-life consistent erasure of female relatives; it’s a feature, not a bug.

“[…] in literalizing legal and economic structures the Gothic mode allows for a demystified and thereby skeptical reading of such structures, encouraging the reader to see the horror implicit in seemingly mundane systems of oppression. Thus, to a degree, all instances of literalization are implicitly subversive.”

II. “The Fall of the House of Gucci”

or; the Gothic tradition inherent in luxury [fashion] business models

“I think that fashion, for a long time, has been in a prison. Without freedom. I think that without freedom, with rules, it’s impossible to create a new story.”

Quote by Alessandro Michele for the New York Times (2016)

The idea of a Gothic foundation latent in the luxury fashion business model came to me in late 2021, during my time at London College of Fashion. Surprise, my dear, I have a fashion management degree! I contain multitudes, as Walt Whitman said. During one of my luxury fashion management classes, my professor was giving a lecture on Kapferer and Bastien’s two industry-leading luxury management books, and he glossed over a specific phrase; luxury relies on a “chest of symbols”. That one small, seemingly insignificant collection of words has since rooted itself squarely in the slushy pink matter of my brain, fermenting and mixing with my developing interest in [Gothic] literature. Which is how we got here, to this epiphany.

Luxury fashion, actually, is a deeply Gothicised institution and industry; its workings and trappings and problems closely mirror that of literary Gothic tradition. There’s a long list of parallels between the two. So forgive me for jumping ahead of the charge here, but if luxury fashion’s problems are distinctly Gothic, perhaps, its solutions can be too…? I suppose that remains to be discovered. First, let me paint you a picture. One with winding corridors, family trauma, and even a little bit of blasphemy on the side. A uniquely Gothic blend of components, for a Gothic parallel.

II.I the Language of LOEWE.

“Gothic was originally anything but a term for distinctive literary motive horror, terror and awe-inspiring wonder. Rather, from the time of antiquity onwards, the Gothic in British culture encompassed such divergent meanings as the name for a barbaric Teutonic tribe, a sense of the medieval period or "Dark Ages ", an anti-classical impulse in cultural life, an uncouth excess or savage wildness, a distinctive European architectural style, a native tradition of Englishness, a sense of the national British past and more”

by Dale Townsend, from “Terror and Wonder: the Gothic Imagination” (2014), p.6

The language of the Gothic literary tradition, like the language of luxury fashion, is one that is overwhelmingly semiotic and symbolic. They are a genre and an industry that escape the confines of definition almost altogether— a fact that academics tend to return to time and time again in their attempts to analyse either. According to “the Oxford book of Gothic tales” (1992), “[The Gothic] seems to work by intuitive suggestion rather than any agreed precision of reference” (p.XI). In the same vein, luxury is a term not only of a suggestive, fluctuating meaning, it has also lost meaning due to the lax manner in which it is assigned en masse: “Instead of clarifying the concept of luxury, this semantic creativity only adds to the confusion: if everything is luxury, then the term ‘luxury’ no longer has any meaning.” (by Jean-Noël Kapferer and Vincent Bastien, from “the Luxury Strategy”, 2012, p.1).

So then, how does one compare the two? Well, fret not, my dear, for the answer lies in association, in exclusion. It is much easier to find what’s associated with Gothic than to foolishly attempt to create a definitive list; it is a genre of hauntings, of the past coming back, of melodrama, the supernatural, and the uncanny. Additionally, it is easier to say what isn’t luxury than what is; luxury isn’t affordability, it isn’t accessibility, it isn’t ephemerality. The very essence of luxury thrives on exclusion, because luxury is about desire, about dreams, about indulgence. Luxury plays hard to get— been there, done that.

Interestingly enough, indulgence is a strong theme for both Gothic literature and luxury, though in nearly polar-opposite ways. Throughout its rising popularity in the 17- and 1800s, Gothic was considered “cheap” or “vulgar” literature for the masses; overly reliant on irrationality and superficial emotions; it was the anti-curse of enlightenment. Later on, when the genre got banished to cheap short stories and mass-printed paperbacks called “Penny dreadfuls” (named after their low price and content respectively), they died of death by a thousand cuts through being branded as “lowbrow” culture. Pure indulgence, guilty pleasure, hedonic entertainment you hide when someone’s looking. '“Quick, shove the paperback into the couch, I hear footsteps!” Luxury, on the other hand, while it stretches across the spectrum from inconspicuous to conspicuous, is definitively “highbrow”, or, not for the masses. But it has the same emotive underpinnings. A love for luxury rarely has rational foundations: it exists in the realm of excess, of pure emotion. It’s associated with pleasure-seeking excess, all the way.

II.II Home is where the Hermès is.

“Typically a Gothic tale will invoke the tyranny of the past (a family curse, the survival of archaic forms of despotism and of superstition) with such weight as to stifle the hopes of the present (the liberty of the heroine or hero) within the dead-end of physical incarceration (the dungeon, the locked room, or simply the confinement of a family house closing in upon itself).”

by Chris Baldick, from “the Oxford Book of Gothic Tales” (1992), p.XIX

If the overlap between Gothic tradition and luxury fashion would be presented as a Venn-diagram, the overlapping section would be best summarised in just one word: “house”. It’s a simple word, only five letters strong, but it contains at least two meanings and a dozen more uses. Don’t underestimate it, my dear. Consider this: the ancient families of yore, who referred to their bloodlines as the noble “house” of xyz. Consider the “House of Dior”, the “House of Gucci”, the “House of Hermès”. Consider the house as a place, a home. But also as a place of suffocation: the haunted house, the trappings of a sprawling mansion, the looming manors of the Gothic.

The stage for Gothic transgression is often the ancestral home, that icon of pop culture, the Victorian architecture both grand and grave. The sheer grotesque excess of the property itself is a signifier of class. Or rather, it is a signifier of class to be able to own property at all. It is a house heavy with the weight of history, which in its self-important spectacle represents the bloodlines and dynasties of the rich and powerful that inhabit it. When luxury fashion in turn refers to the “House of Dior”, for example, it is absorbing this facet of its wording; luxury fashion as the idea of pure legacy distilled. Yet the wording also draws us to envision the brand as a place, a monolith immune to time, a structure of imposing eternity. The terminology reinforces the central idea of luxury as timeless, classic, that it will outlive us for decades if not centuries to come. The people may leave but the house remains.

Ridley Scott’s 2021 drama film “House of Gucci”- a sensationalised retelling of Gucci’s rise as a fashion house, and the subsequent fall of the Gucci family due to infighting- isn’t coy linking the health of the House of Gucci, that is; the brand, with the health of the House of Gucci, that is; the family. Today, Gucci is one of the largest luxury houses in the world, but it is also, notoriously, known for the murder of Maurizio Gucci, who was tragically assassinated by a hitman his ex-wife had hired and paid for. The House harbours a deep history, both of fashion, and of family.

Family drama is not just unique to luxury fashion, of course. But it serves the parallel we are just beginning to draw here. This is the sketching phase. Family ties, legacy, and houses (both literal and figurative) play a large part in the connecting tissue binding luxury fashion to the Gothic and vice versa. A staple in Gothic literature is its deep emphasis on familial connection: plots often revolve around marriage (“Jane Eyre”, 1847, “Rebecca”, 1938, “The Tenant of Wildfell Hall”, 1848), or [implied incestuous and] twisted family relations (“The Monk”, 1796, “Flowers in the Attic”, 1979, “Wuthering Heights”, 1847). In the first ever Gothic novel- Horace Walpole’s “the Castle of Otranto” (1764)- it is a wedding, and a subsequent question of inheritance and bloodline that drives patriarch Manfred to his incestuous madness and sets the plot in motion.

“Turrets, basements, hungry ghosts: the house is where the Gothic comes home, but only to undermine the very foundations of the concepts of ‘home’.” // “The Gothic always comes home, but to a house made unheimlich by haunting presences that cry out for their story to be told”

both by Roger Luckhurst, from “Gothic: an Illustrated History” (2021), p.57 / p.68.

But the house in Gothic is also a pressure cooker for secrets and scandal. Think of the haunted house so fond to the Gothic tradition: early Gothic (1764-18201) was particularly caught up in this idea of the home as the first layer of uncanny; home is where the horror is. The ancestral home is a place of exclusion and seclusion, of buried secrets, a physical representation of aristocratic obsession with the past turned claustrophobic. Famously, this results in what some would refer to as “corridor Gothic”, which is the emphasis Gothic literature and its multitude of adaptations place on the corridor or hallway in particular. Synonymous with the genre is the vision of a heroine in a white nightgown, exploring winding passageways with only a gilded candelabra for vision in the dreaded darkness of night.

This exploratory claustrophobia has distinct psycho-analytical purpose: “‘we pace the rooms and corridors, whose long perspectives display a simple nobility of line’ then enter ‘passages, which are extremely numerous, winding and narrow, so that they form a veritable labyrinth’” (by Eino Railo, from “The Haunted Castle: A Study of the Elements of English Romanticism”, 1927, taken from Roger Luckhurst’s “Corridor Gothic”, 2018).

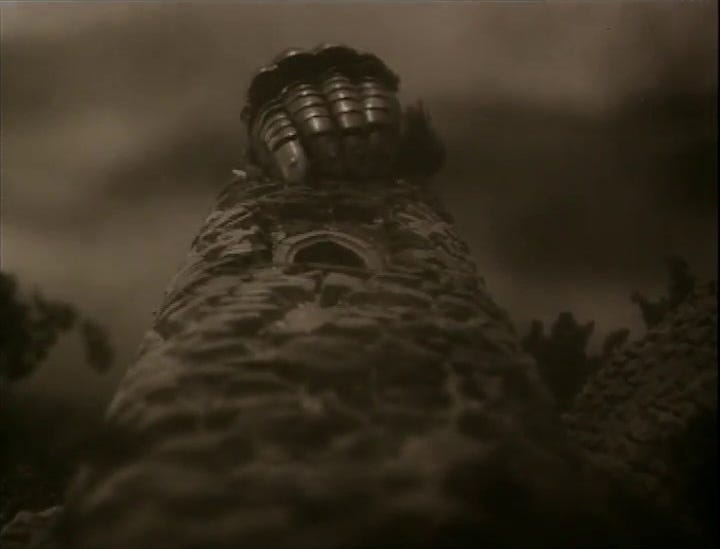

In Guillermo Del Toro’s 2015 Gothic romance film “Crimson Peak” this is further enhanced by the design of the corridors itself; the silhouette of protagonist Edith’s mother, whose ghost was the first to warn her about the accursed titular “Crimson Peak” manor, is reflected in many places throughout the film, but mainly in the monstrous manor’s ominous hallways, where it takes on a sort of menacing, teeth-lined shape. The family, supposed to be a safe haven, gains an appetite for hostility. Add to that that the film’s villain’s are motivated by inheritance and wealth, and you get the unique flavour associated with the genre. Houses are representations of the families that inhabit it, and its architectural features, the grand, surreal spaces of the manor, the winding intestines of its halls, also serve to highlight class as a grotesque animosity.

Above: clip from “Crimson Peak” (2015) depicting the corridor in question. Notice the outlined shape of shoulders and a head, as well as the spiked “teeth” adorning these. Original Image Source: see film, filtered B&W.

The Gothic tradition, then, is uniquely focused on a world of the upper classes. One of long lineages, and family estates, and legacy. It is a world one must buy into to be enjoyed, but the pleasure is twofold: it exists both as a critique of the upper classes to the reader (Look at this depravity hidden under the veneer of superiority!) and as commodity fetishism. Part of the consumptive properties of the fantasy it offers is that very notion of buying into a world only birth can grant you access to, as is true for luxury fashion. Even for the ultra-wealthy, consuming luxury goods is often about access to a long extinct, mythical era of [mainly Eurocentric] splendour, a gilded age, and rich extravagance.

This fantasy of “old” money is valuable currency in itself. It’s added value for a brand. An invisible marker of explicit value in their products. It’s nostalgia-bait for a time that has never existed for the majority of people, and never will. It’s a constantly moving lure— always a world to be excluded from, always a world not yet seen, always a world tragically missed out on. The prestige becomes the product, which is what we call the “halo effect” of luxury: it creates a golden ring of light, of privilege, of rarity, of exclusivity, that makes people clamour to be a part of it, to buy a part of it.

II.III This is the Body, this is the Blood, this is the Balenciaga.

“There can be no luxury brand without roots, without a history to provide the brand with a non-commercial aspect. This history constitutes a fabulous treasure to the mythologization that it enables, by creating a sanctum of uniqueness, of non-comparability, while being the origin of an authentic lineage to which each new product can lay claim period.”

by Jean-Noël Kapferer and Vincent Bastien, from “the Luxury Strategy”, (2012), p.93

Returning to Ridley Scott’s “House of Gucci”, there is another facet of Gothic tradition to be pointed out in luxury fashion, which is that of the supernatural, and by extension, that of superstition and religion. The film depicts the grandiose fall of the Gucci family almost completely devoid of subtlety; at one point its fictionalised Aldo Gucci asks Patricia Reggiane (then-wife of Maurizio Gucci) if she can keep a secret. In response, she crosses herself, supplanting the Christian holy trinity with a brand new one: (1) Father, (2) Son, and (3) House of Gucci. Clearly, the self-aggrandisement of the family legacy has reached new horrifying heights. The institution of Gucci, the “house”, has become a secondary, living thing, insistent on its own survival no matter the cost. It has reached eternal divinity and has become a god, complete with worshippers, subjects, and feverish devotees.

Religion is important to the Gothic in the sense that it is both ruled by it, symbolically, and at odds with it— the rational carries very little weight in its world of spectres and miracles. As a result, the Gothic likes to deal in superstition, just like luxury fashion does. Fashion designers are, in fact, known for their involvement in and adaptation of a large codex of superstitions and rituals unique to their craft. Some of it is fairly pedestrian, like the common obsession with numbers of perceived importance: Coco Chanel famously scheduled her shows for the fifth day of the fifth month, Christian Dior held a near-mythical belief in his lucky number, thirteen, and for Karl Lagerfeld it was the number seven that seemed to grant him protection and success. It is no wonder then that for their SS21 collection, the house of Dior decided to invoke one of the oldest divination practices in the world: tarot.

All of the mythicism slots neatly into the luxury fashion mindset because the rational has fundamentally little place in the foundational ideas of luxury, which are affective and hedonic. So why would it be any different in its practices, my dear?

There is much more to say for the religious aspects of luxury. Besides the fervour it inspires in its initiates, its very business model mirrors religion. By default, luxury fashion is a lineage which deifies not only the original founder (the Father), but also the current creative director or designer (the Son) to near-mythical levels, something which we will return to very soon. If the original founder is the brand’s “god”, the current creative director is the prophet interpreting the gospel (brand vision) into verse (product). Kapferer and Bastien agree, even going so far as to structurally compare the “cult of luxury” to religion. Highlights include notes like:

“They [both] have a creator.

They have a founding myth and legend.

Storytelling will maintain mystery about them.

There will be a holy land, or holy place where it all started.

There will be a chest of symbols (logos, numbers, signs, etc.) whose signification is only known by those who have been initiated.

Luxury brands will have icons (products endowed with a sacred history).”

by Jean-Noël Kapferer and Vincent Bastien, from “the Luxury Strategy”, (2012), p37

II.IV the Aesthetics of Prada Purchasing Power.

“The parallelism between religion, art and luxury is striking: all three are concerned with eternity, or at least timelessness.”

by Jean-Noël Kapferer and Vincent Bastien, from “the Luxury Strategy”, (2012), p.36

Make no mistake, the aforementioned mysticism serves a real purpose: it is a balm for a notoriously fluctuating industry, both commercially and critically. Valerie Steele, director of the museum at the Fashion Institute of Technology, explained it promptly: “The idea that superstition comes in part from a feeling of a lack of agency and financial anxiety would be significant for people in fashion because it does so much seem like you need luck to get ahead,”2. The logical result of such an abstract concept as luxury is that selling it, also, becomes an increasingly abstract practice. And there is no forecasting the abstract. Gone are the days of simply fulfilling a need. The luxury fashion marketer is a meta-physician3 selling a product that exists beyond just the qualitative, textured, and tangible.

Therefore, the power of aesthetics, especially when it concerns the superbly evocative and associative world of luxury fashion, is of the utmost importance. Fashion as both an art-form, a need fulfilled, and an industry are hugely important to consumer identity construction— luxury fashion especially so because of its emotional value as a social cue, and because of its intrinsically motivated value ascribed through the consumer’s attitudes towards luxury. The hedonic or emotive side of the luxury fashion coin holds equal, if not more, weight to the actual characteristics of the item in question, as we have seen. Selling a dream requires selling atmosphere, requires selling visuals, requires selling in non-tactile terms like “experience”, “heritage”, or “legacy”.

The semiotics and symbolism of the luxury brand are primary concerns in its brand management. Studies have shown that higher consumer engagement with branding (and its main lieutenant, advertising) have resulted in higher effectiveness. If sales are the end goal, engagement is the fight, and visual potency is the weapon. Yet these preferred weapons of luxury fashion, that take the form of symbols, visuals, association, meaning, and beauty, are time and time again entwined with those of the Gothic literary tradition, or are in close association with it.

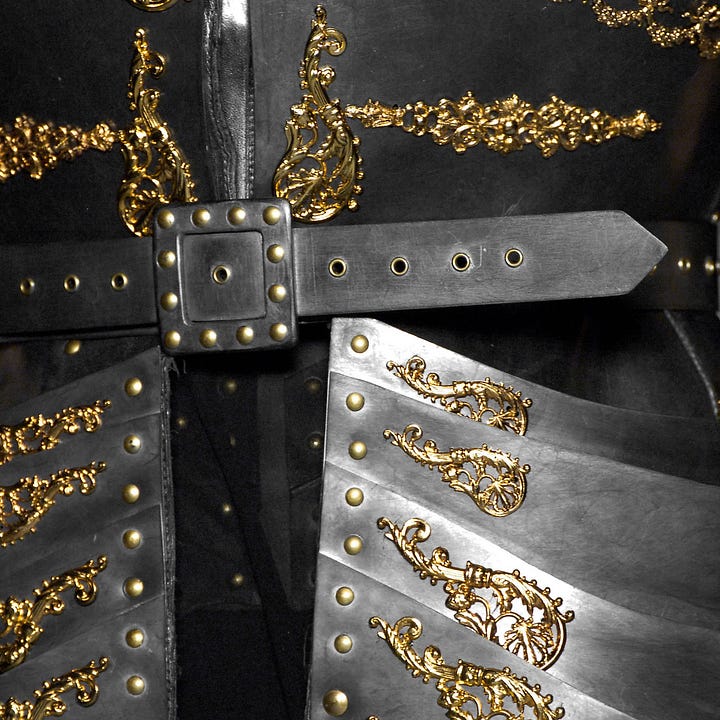

Heraldry, for example, plays a big part in luxury fashion’s “chest of symbols”. Just two years ago luxury fashion brand Burberry reverted from their minimalist sans serif typeface back to a serif font, with matching heraldic inspired logo, and a monogram inspired by its founder Thomas Burberry. The switch represents Burberry as a brand, as a house, drawing from its own history again. The logo takes the form of a horse-mounted knight, which wouldn’t be misplaced in an adaptation of “the Castle of Otranto” (1764): the novel features many surreal passages in which a suit of armour reaches gigantic proportions. The pieces of it pepper the plot in prophetic ways; the large helmet becomes an impromptu jail cell, a giant hand obstructs view, and parts of a leg and foot cut off a chase. Through these incidents, the castle’s past becomes life-size and oppressive, and yet it also stirs the plot into renewal.

In much the same way, the Burberry knight is both a charge forward and a glance back. It’s the sort of logo one associates with a Poe, or an Usher, or any other tangled root of a classical [Gothic] family. That Gothic drama, as we have seen, is often family drama, is often a story of lineage, of cycles, of recurring patterns. But it is also colloquially a genre associated with a range of symbols, tropes, and motifs— from the woman in white to the ghost in the corridor. Visually, the Gothic is often parodied as a game of ticking boxes. This is also represented within Kapferer and Bastien’s “chest of symbols” that luxury relies on. And like the luxury brand Gothic tradition is equally caught up in regurgitating these symbols, tropes, and motifs to reinstate its own positioning, as it is trying to continually tweak and twist them in the slightest ways to differentiate itself. Both the Gothic and luxury fashion inhabit a world of continuous friction between tradition and innovation. A strained relationship, you could say.

II.V From son to son to Saint Laurent.

“The Gothic theme that the sins of the father are visited on the offspring is manifested in the representations of the illegitimacy and brutality of paternal authority, the repetition of events, and the doublings of figures and names in successive generations.” (idiom)

by Fred Botting, from “Gothic: the New Critical Idiom” (1996), p.84

We’ve demonstrated that luxury fashion relies on a language and symbolism rich in near-religious importance, heritage, dramatics, superstition, and heraldry that would be considered, in other circumstances, synonymous with the tradition of Gothic literature. Its world is, in turn, uniquely concerned with the narratives of its own past. The Gothic present and Gothic past often inhabit the same story, where instead of being sequential to one another, they are layered, stacked, and even interlaced. The de facto model of this modus operandi is “Wuthering Heights” (1847), in which the reader is jumping between finding out about the past, and seeing its effects in the present in alternating sections, sometimes completely doing away with the linear structure and its continuity.

This self-referential nature is shared with luxury fashion, which is always calling back to its own heritage, its own signatures, its own history. The Gothic structure and the luxury fashion brand love a meta-reference to themselves, but their history within is still mostly linear in its patriarchal model. In Edgar Allan Poe’s “the Fall of the House of Usher” (1839), he writes that the “ancient” race of the Ushers is unique because “the stem of the Usher race, all time-honored as it was, had put forth, at no period, any enduring branch; in other words, that the entire family lay in the direct line of descent, and had always, with very trifling and very temporary variation, so lain.”. Similarly, luxury fashion brand extensions are often tricky business: the tree doesn’t do well with growing new branches, my dear. So, the Gothic family model operates on a continuous patriarchal renewal, a handing down of family legacy, lore, and home from father to son and so on. And it’s this ritualistic repetition that moulds itself into the curses of Gothic literature we are so often familiar with.

Like in the Gothic family “houses” of days past, their sprawling deep-rooted family trees now mostly died out, names in luxury fashion are passed down and treated with near-religious significance. Brands like Alexander McQueen or Yves Saint Laurent (now simply “Saint Laurent”— note the layers of symbolism in fronting a brand with “Saint”) directly take their name from their founding “fathers”, passing it down through generations of employees, customers, and designers alike.

But in contemporary luxury fashion, it is not only the founder’s name that radiates and shines, but the designer’s name. Simply referring to “Dior” is not enough, its eras will be broken down into “Marc Bohan’s Dior”, “John Galliano’s Dior”, and “Maria Grazia’s Dior”. Quote: “A most significant shift is taking place: the starification of designers. There is a real cult of the designer. Unlike the artisan, famous for his or her know-how, designers now beg for recognition as real creative artists” (by Jean-Noël Kapferer, from “Kapferer on Luxury: How Luxury Brands Can Grow Yet Remain Rare”, 2015, p.46).

But the newly deified designer has a heavy history to inherit. Cumulative history is the Achilles Heel of both luxury fashion and Gothic literature. The weight of it is crushing, and often disparaging, and can drive one to madness with relative ease. It is both a strength and a weakness, a flaw and a peculiarity, a draw and a con. The Gothic often gets shelved away for being formulaic, especially when it comes to its settings, symbols, and sumptuous motifs. To match, luxury fashion is always in conflict with itself, and its creative directors are always in conflict with the history of the house they inhabit and represent. But for it to live, it has to breathe. It has to expand and transform itself to keep the attention of consumers. Stasis is the death of progress, and the fashion industry is notoriously fickle. The luxury fashion-focused film “Phantom Thread” (2017) emphasises this friction when it has its designer say “A house that doesn't change is a dead house”.

It’s a tricky thing: when brands innovate, they might damage the house’s legacy by straying too far off the beaten path of the consumer’s imagination. But if the innovation does pay off, it is only an invisible countdown until that very newness turns on itself. The walls of the house are ever crumbling, ever at risk of caving in, like the walls of the house of Usher in Edgar Allan Poe’s story. The cracks can be pasted over, but they will always return. Thus, luxury fashion tends to be deeply cyclical, paying homage to- and selectively discarding the past in alternating waves. The very model of luxury fashion, its collections divided seasonally, reflects this, and mirrors the Gothic’s obsession with cycles of violence, doubling, and repeating events.

The aristocratic obsession with bloodline within the Gothic is a stifling environment for the individual. Likewise, the hallways of the manor of the endlessly re-treaded “heritage” of a luxury fashion brand, often are a tightrope for its creative directors and designers. The inevitability of it all is the crux of the issue: violence is cyclical like trauma is intergenerational. You can escape your house but you can’t outrun your name. Singer Ethel Cain opens her decidedly Gothic debut album “Preacher’s Daughter” (2022) by singing about the lack of control that comes with the weight of family history: “Jesus can always reject his father / But he cannot escape his mother’s blood”, and later on, “The fates already fucked me sideways / Swinging by my neck from the family tree”. Gruesome perhaps, but apt nonetheless.

II.IV It’s Versace, not Versa-she.

“Most of the essential Gothic elements are present: the disorderly transfer of property, the decay of the appropriating dynasty and the patriarchal suppression of the female characters.”

from Archive Source 3

Like the Gothic family structure and drama is largely patriarchal, luxury fashion is, even to this day, mostly the same. The overwhelming majority of luxury fashion’s creative directors are still male (and white!), as Vogue pointed out this past February. Though the luxury fashion industry caters disproportionately to women’s imagination, with arguably most of the creative innovation driven by its womenswear collections, it is not one actually created by women for women. The system of inheritance that Gothic literature historically operated under, functions the same way: the common law of primogeniture only allowed a passing down of estate and wealth to a female heir when there were no male heirs present, effectively “erasing” the “female presence” within the line of inheritance (see Archive Source 3).

The face on the covers of Gothic novels is often female, as a genre noted for its heroines; its audience was and still is overwhelmingly female, and its authors, too, were more often than not women. Luxury is also a female-focused discipline. Unsurprisingly, some studies have concluded that “overall, women have a more positive attitude toward and a higher purchase intention of luxury brands versus non-luxury brands than men.”4. And yet the faces of these brands are still the vast majority of the time white and male, even when their biggest audience5 demographics lay outside of those signifiers.

I am frighteningly aware that I have just ranted at you for a non insignificant amount of time, my dear, only to offer up very little certainty in terms of solution. All the facets of luxury fashion we have just spent however many thousands of words unpacking mean that we really can’t predict where the industry will go, what its problems are or will be, never mind what balms to apply to its various ailments. It turns out that enduring legacies are in their own ways, surprisingly ephemeral.

Despite all the talk of stifling heritage, there are brands that do better when they leave such notions behind. Gucci, for example, thrived under creative director Alessandro Michele, who side-stepped a lot of the brand’s equestrian heritage in favour of his own brand of funky maximalism— perhaps because Gucci’s equestrian “heritage” is, in part, a fabrication of its own myth-making machine of which the origins aren’t known. In 2001, Grimaldi Gucci was quoted as saying; “I wanted the truth to come out. We were never saddlemakers”.6 Maybe it wasn’t so much the disavowal of said heritage, but the playfulness with which it was treated that brought Michele’s Gucci such commercial and critical success. After all, Michele never abandoned the horse-bit loafers. He just gave them a new printed, furrier look.

Perhaps to run a successful luxury fashion brand, one must learn from the Gothic stories that succeeded it. Very rarely does the heroine victorious stay in the haunted house to set up residence. And while the collapse of the house is absolutely the last things that could ever be of use to luxury fashion, a new coat of paint and some new inhabitants might serve it well. The most successful contemporary Gothic novels (Anne Rice’s “Vampire Chronicles”, 1976-2018, Carmen Maria Machado’s “Her Body and Other Parties”, 2017, Gillian Flynn’s “Sharp Objects”, 2006) have been intersectional, women-led projects that focused on expanding the genre and bringing the previously invisible or overlooked into its arms. So there is definite hope for a new dynasty to be built on the bones of these old houses, to bring new life into them.

The house need not be haunted, it could just be a home.

III. Museum Recap: April.

“Admire as much as you can, most people don’t admire enough.”

by Vincent van Gogh, from a letter (ca. 1874)

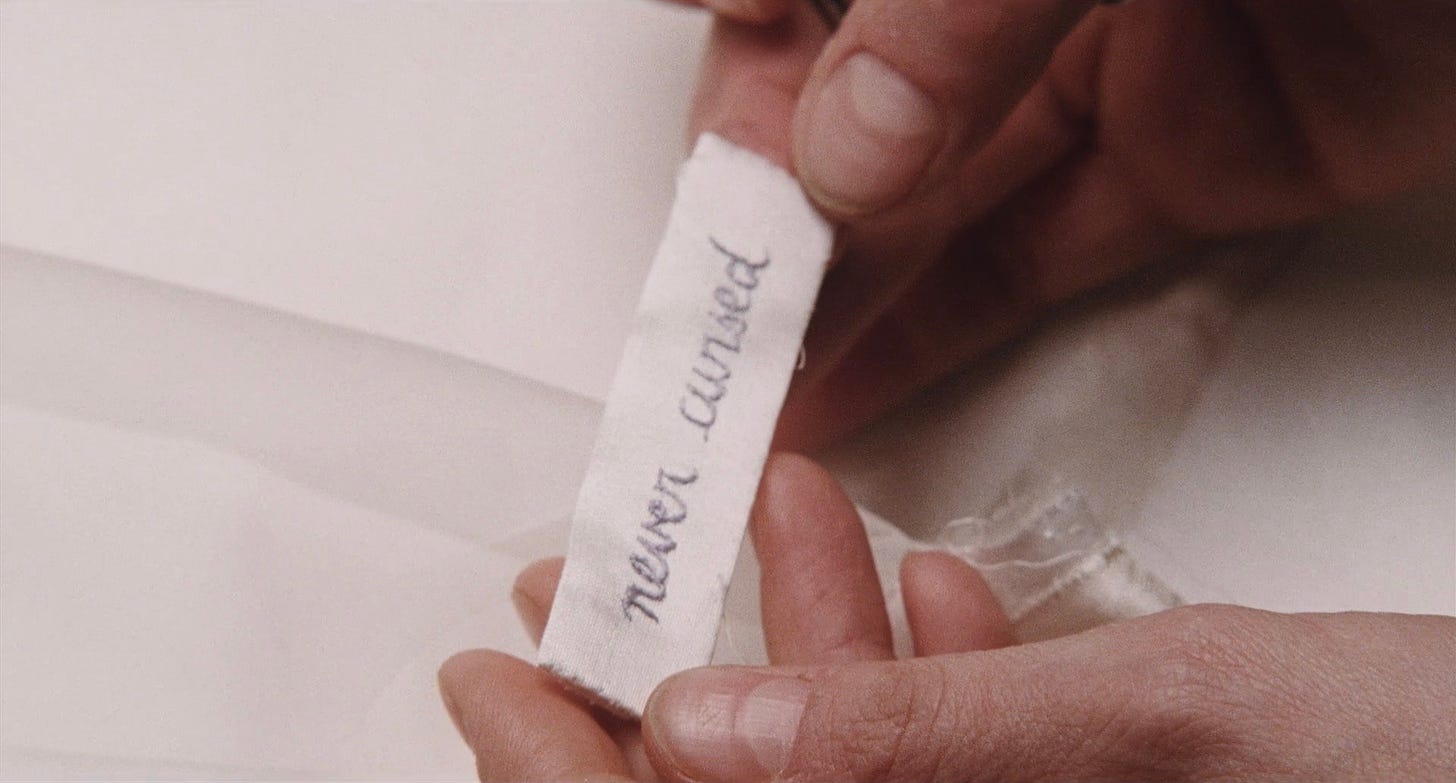

Now, my dear, you know it is our long-standing tradition of de-briefing the past month’s exploits with a cup of tea and a monologue of mine. As a very busy girl, I tend to go to many new places, to which I carry you with me in my mind, and then I circle my thoughts back to you afterwards via digital lettering. Much more efficient than keeping a gaggle of carrier pigeons at one’s house. Nevertheless, April has been a busy month, as usual, with many fresh sights explored, so allow me to indulge in telling you all about them. Brevity be damned! The pen is mightier than the sword, and much more addictive. It should practically be sold with a warning label.

☆ the Sir John Soane’s museum, Holborn, London

Sometimes you can be right on top of something and somehow still miss it. That, my dear, is the story of me and the Sir John Soane’s museum. Positioned right behind my former university, I’ve eaten many lunches in the park across from this museum without ever noticing the Victorian splendour located only a stone’s throw away. It’s a free museum, and quite a lovely one at that. Sir John Soane, in his lifetime, aimed to create a place where architecture, sculpture, and painting could meet and blur, and he certainly accomplished that. There’s something for everybody here: the hundreds of small mirrors, tinted skylights, and other architectural flourishes give the house a wonderfully surreal nature, which is aided by the sheer multitude of art objects on display. Though my favourite was certainly the odd glass casket in the basement, which was very “Sleeping Beauty” indeed— and you know how I love that tale.

☆ “Omens, Oracles and Answers” at the Bodleian Library, Oxford

Despite my having written about seers, prophetesses, and oracles in near-excruciating detail before7, there is always much more to be learned. Me and my dear friend Anna de Waal took a day-trip to Oxford just to see this exhibition before it closed, and it was most certainly worth the train travels! Oxford in itself was completely new to me (due to be explored more in-depth ASAP), but the exhibition took centre-stage for the short day we spent in the town. Some of the most delectable bits included learning about ancient Chinese dream hostels, spider divination in Cameroon, and Oscar Wilde’s fascination with palmistry. The spiders in particular were endlessly fascinating, truly. I suppose all that’s left for me to do is chase down one of the little eight-legged guys so they can tell me all about my webbed future. It gives a whole new meaning to the “tapestry” of fate, doesn’t it?

“The most popular form of divination in Cameroon in Central Africa involves tarantula-like spiders or land-crabs. The spiders, called ngámbi, live in holes in the ground. When consulting, ngám diviners place a stick and a stone near a spider's hole, which is covered with some marked leaf cards. As it emerges from its hole, the spider moves everything around and the resulting pattern is interpreted by the diviner.

Ngám divination is used for everyday concerns such as the best treatment for an illness, whether to buy a motorbike, and to identify thieves. It is also used to adjudicate witchcraft accusations in the chief's court, and to decide among candidates who will become the next chief.”

from the “Omens, Oracles and Answers” exhibition text (2024)

✧・゚: *✧・゚:* On the List *:・゚✧*:・゚

Exhibitions, Events, and Talks. Starting off strong, the incomparable electro-witchy-folk band “Weaving in Purgatory” is holding a live recording session at the George Tavern this May 11th, which promises to be electrifying and dizzying and spellbinding; be there or be square. Or, if you prefer a curated and experimental lineup of varied artists reflecting on the body as a vessel, there’s “A Woman Becomes A Wolf presents: we go up into the sun” on May 4th.

May is looking to be a strong month for film. Haunted house fans pay attention because the BFI is screening the classic Shirley Jackson adaptation “the Haunting” (1963) on May 10th. The re-release of 2005’s “Pride and Prejudice” has also kicked off (with hand-flexes). If you love this film most ardently, there are screenings available at the BFI on the 1st (today), 4th, 5th, 7th, and 8th of May. For something even more fantastical, “Deeper into movies” is adding to its always-stellar lineup by screening cult classic “Valerie and her Week of Wonders” (1970) in Dalston on the 3rd, and “Buffalo ‘66” (1998) on the 10th. Tickets are £5-10.

Additionally, the new fairytale horror-comedy “the Ugly Stepsister” (2025) is screening at selected cinemas around London, and looks to somehow be equally gruesome and whimsical. Meanwhile, Picture House cinema is proving that Lynchian filmmaking is everlasting by screening selected “Lynchspirations” and David Lynch films for the rest of the year. The lineup for this month contains “Dune” (1984) and “Blue Velvet” (1986), as well as Lynchspiration films “Freaks” (1932), and “Dune” (2021).

Exhibition-wise, do note that “the World of Tim Burton” at the Design Museum is ending on the 26th of this month! Learn from your trusty curator’s past mistakes; if you wish to go, grab tickets sooner rather than later. Additionally, the Freud Museum’s “Women & Freud: Patients, Pioneers, Artists” closes on the 5th— which I highly recommend checking out for princess Marie Bonaparte and some lovely Louise Bourgeois pieces. In other related, very exciting news, Bourgeois’ ten metre tall arachnid “Maman” (1999) has returned to the halls of Tate Modern and is available to marvel at throughout the month of May.

Your calendar need not be lonely this May, for there are plentiful events, free and paid, for you to cheekily pencil in, my dear. The V&A has a free lunchtime lecture on “Spectres and the Supernatural: Victorian Spirit Photography” on May 2nd, which I’ll certainly be attending. See you there? On the 14th, the Wallace Collection is having a talk about the virgin Mary’s depiction in European art— “Imagination and Devotion: Mary and Sacred Art”, tickets £20. Finally, if you’re feeling reflective, the National Gallery has a free talk on “Through the looking glass: Mirrors and reflections in art” on the 29th.

Most excitingly, my dear friend ester freider is publishing her 63-page document “Forever Mediated: Feminist Erotic Texts and the Seduction Economy” with Bimbo Rhetoric on May 5th, which promises to be a long-form meditation on “feminist erotic texts and the seduction economy”. Exceedingly up-my-alley, and yours too, perhaps? Regardless, I know I’ll be devouring it as soon as it releases. You can bet on it.

Film, Music, and TV. Two new projects are coming your way this May: first of all, beloved shoegaze/indie band Newdad is dropping their new EP “Safe” on May 2nd, while bedroom-pop band Sunday 1994 is dropping their “Devotion” EP on the 9th— two releases to perfectly lull us into the dizzying warmth of this upcoming spring month.

I know video games are perhaps not what you’d expect from me, but as a certified FromSoftware fan, I’d be remiss in forgetting to mention that “Elden Ring: Nightreign” is releasing this month on the 30th! Maidenless or not, you can rejoice in having new masochistic delights to die your way through.

Rather embarrassingly, I’ll admit to you now that I’ve never read “Dracula” (1897), despite owning four copies— alright, alright! Please put down your pitchforks. I’m being vulnerable with you because I wanted to tell you about my chosen way to experience the novel as it happens. “Dracula Daily” is a yearly Substack project that sends out the epistolary events of Draculas they unfold in real-time. Join me, if you like, and sink your teeth into daily vampiric delights in your inbox from May 3rd to November 7th.

In the Stars. First of all, happy Beltane, my dear! The spring has now reached its apex, beginning to welcome the warmth of summer. And as the seasons shift, so do the stars. There will be a full moon in Scorpio on the 12th of May, and a new moon in Gemini on the 26th. Now is a time for reflection, right up until the 16th of May when Venus leaves its post-retrograde shadow. Tend to yourself now, so you can bloom again later.

Obsessive Tendencies: What I’ve Loved Lately

Hollister, “Sofia” side-smocked eyelet maxi dress, [I wore this with a matching white lace headdress, argyle tights, and lots of jewellery and got complimented outside of Kings Cross station by a lovely lady! Waif-ish and beloved], £59.95

Aspinal of London, “Musky Fig” Eau de Toilette, [Got a sample of this and been obsessed ever since; it’s both fresh and mysterious, like a voice luring you deeper into the forest], full 100ml bottle £125 // in sample set £25

Ethel Cain, “Preacher’s Daughter” on vinyl, [One of the best albums of the last decade. At times chilling, haunting, and even scary, this beauty sounds even better on vinyl], £21.99

American Crew, hair pomade, [My naturally curly hair is fighting for its life against the British summer— this helps fight the frizz. A lot], £13.55

Miss Selfridge, embroidered chiffon and velvet mini dress, [A classically witchy dress for all your chilling adventures], £49.99

Mariage Frères, Lapsang Chinbara loose leaf tea, [A tea both smoky and seductive; fuels fantasies while I write, locked away in my attic], £17

“And Spring arose on the garden fair, / Like the Spirit of Love felt everywhere; / And each flower and herb on Earth's dark breast / Rose from the dreams of its wintry rest.”

by Percy Bysshe Shelley, from “the Sensitive Plant” (ca. 1820)

Every night as a ritual I have to shine a flashlight into the dark hallway past the doorway of my bedroom, and compulsively check that it’s just me, alone, folded up in my sheets. The darkness can easily grow eyes if you allow it to, so this is me, shining the metaphorical light again. I’m sorry for blinding you, my dear. Supposedly, telling you all about my dreams has become a staple of these outros— as someone with more than a handful of sleep disorders, it’s like a never-ending content mine! Official apologies to ester freider, who had to lay next to me at my sleepover last month and listen to my sleep-dazed mumbling about a dream in which “everybody was cacti, and I was a succulent” and I got put into a “car crusher”. “A car crusher?… Cool” she replied, and swiftly fell back asleep. I don’t blame her at all.

To violently change the topic, I’m off to the Swiss Alps again for the beginning of the month of May, planning to frolic in the fields and recite poetry and see my dearest friend Lily8 again. It’s been far too long since I’ve indulged in everything Venusian with her. My one big intention is to sink into the niche and abstract, let my friends show me it’s okay not to wrap everything up in neat little ribbons, to leave the ends uncurled or even frayed. Not abandoning perfectionism anytime soon, but revelling in the art of retreading familiar ground. At the erotica sleepover I hosted last month, we talked about sex, and death, writing, religion, and love while 1940s gramophone music played in the background, and we ate lots of fruit. The meaning of life is hidden within a blackberry, I believe.

Affirmations for a tender spring (repeat after me)

The bloom that begins in me will also bloom in the world

I am the sacred architect of my own endurance

Every ritual that I softly devote myself to is another way of worship

Until my next letter,

With love (and violence),

x Sabrina Angelina, the White Lily Society

Currently reading: “Agua Viva” by Clarice Lispector // Most recent read: “Carmilla” by Sheridan Le Fanu

White Lily Society links // Sabrina Angelina links

The most luxurious thing in the world perhaps, the greatest indulgence, is knowledge. So why not receive a fresh dose of the Intersection of Love and Violence, Gothicism, and Romanticism in your inbox every month? Come, join the White Lily Society, and become a martyr of deliciousness.

📼 Song of the (past) month: “Nightmares” - NewDad

Time period taken from “Terror and Wonder: the Gothic Imagination” (2014)

Credit for this phrase goes to Melinda Davis, who first noted it in her book “The New Culture of Desire: 5 Radical New Strategies That Will Change Your Business and Your Life” (2002) - link

As found by N.E. Stokburger-Sauer & K. Teichmann in “Is luxury just a female thing? The role of gender in luxury brand consumption” (2013) - link

The biggest luxury consumption growth comes from Asia, as continually reported on by the Business of Fashion. See also: their “State of Fashion 2025” (2025) report

See M. Defanti, D. Bird, & H. Caldwell, “Gucci's Use of a Borrowed Corporate Heritage to Establish a Global Luxury Brand”, (2014) - link

I am all about unabashedly promoting my friends, so go check out her yoga / cacao / EFT / meditation / wellness business “Sol Altar”: they’ve recently started a YouTube channel where they do yoga and meditation videos, which I cannot recommend enough.

I feel like I've gained a new level of sight with this- amazing, now I see the many connections between luxury fashion and gothic literature!

genuinely enjoyed reading this! I can tell that you put lots of effort into it and it was interesting reading how you connected the dots between gothic literature and luxury (fashion)☺️I love a smart woman!