11. As foretold

The one which was prophesied.

“In the deepening spring of May, I had no choice but to recognize the trembling of my heart.”

by Haruki Murakami, from “Norwegian Wood” (1978)

This month’s newsletter contains one extremely brief mention of sexual assault in the “Cassandra” paragraph of Section II. Though it’s barely there, I wanted to add this trigger warning just to be safe rather than sorry. Reader discretion is advised, as always.

01/06/2024, London, UK

My dear,

Shakespeare wrote that “Rough winds do shake the darling buds of May” (Sonnet 18), and just for today, just for this one letter, I am inclined to agree with the good old bard. Oh me, oh my! What a whirlwind the past month has been!

I spent my May disappearing into myself in all the best ways. Or rather, clawing my way out of myself again. It’s odd how you never notice you’ve disappeared until you’ve re-appeared again. May has been a balm to the soul, filled with cups of tea, and new friends, and enough art to even make me wince a little (It’s true, I vowed to be sober from museums for the rest of the month). I guess I never really expect much from May, and that’s how it sneaks up on me in the end. Or the beginning. No, scratch that. It’s definitely the middle. Either way, low expectations breed surprise. That much I know.

The spring is making my heart beat stranger. Making me wish for darker hair, pre-Raphaelite lovers, Greek mythology tragedy, a bracelet that reads “sacrificial lamb”, and haunting folk music. Flowy white dresses all handled carefully in blush-coloured beet-stained hands. Mornings coughing up pomegranate seeds. Lockets with nothing but you, you, you. Forgive me for rambling on. It costs me much more to hold it in than to let it all flow. Let us continue on.

Gather here, come one, come all! Fresh new White Lily Society endeavours on display, get them while they’re hot and the ink is still drying! This past month, there have been short write-ups about Sargent and impressionism, about Sylvia Plath and a cultural fascination with dead women, and about a Czechoslovakian adaptation of "Beauty and the Beast" that I very much adored. Then, the very first, very exciting submissions to the White Lily Society substack started rolling in! I slipped into my role as editor with grace, of course, and with my usual harsh eye for revisions (my apologies to all who had to deal with it). The first published submission is a personal essay on AI, maladaptive daydreaming, and loneliness, and the second is a much more light-hearted piece on solo-travelling (and sending love telepathically). Both are wonderful, and I can’t recommend them enough. Do check them out.

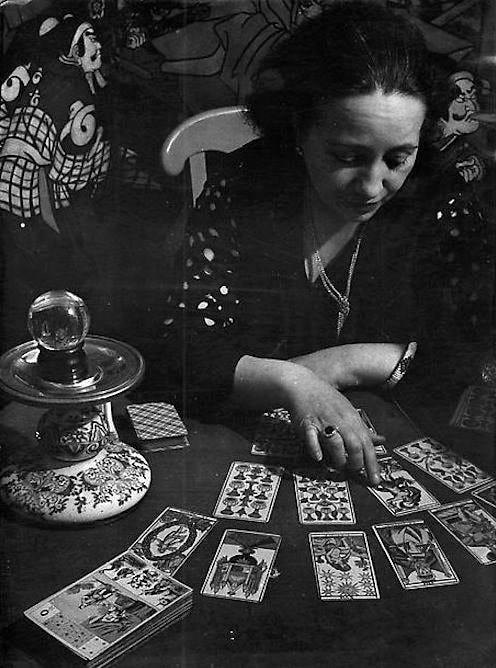

Now, prepare your crystal balls, your tarot cards, your imaginative minds. Let’s talk about fortunes and prophecies. Don’t act like you didn’t see it coming!

I. Archive Updates

“Predictions are uttered by prophets (free of charge); by clairvoyants (who usually charge a fee, and are therefore more honored in their day than prophets); and by futurologists (salaried). Prediction is the business of prophets, clairvoyants, and futurologists. It is not the business of novelists. A novelist’s business is lying.”

By Ursula K. Le Guin, from “The Left Hand of Darkness” (1969)

Don’t worry, I’m not lying when I tell you that the theme for this May’s newsletter is “seers, oracles, and prophetesses”. We’ll be taking a closer look at a variety of ancient prophetic practices, divination, tarot, tragic fortunes, and a little bit of witchcraft. Many of these topics do have a small overlap with the concept of “Necromancy”, something which has been covered in Issue 04 of this very newsletter, so it would be wise to consult that specific newsletter when you’re lost, as I won’t be recapping too much in favour of covering newer ground. With that said, let’s discuss some academic articles.

Finding good academic readings on the occult and esoteric is always a straining endeavour, as you’ll inevitably be met with the pompous, the obtuse, the unnecessarily cynical, the dense, and the painfully skeptical. Truthfully, I spent more time in the past few times going through dud articles than I’d like, but I’ve succeeded finding three shining jewels that managed to fit my high standards. Only the best for you, of course.

“The Delphic Oracle” - link

Analysing the attitudes towards the Oracle of Delphi in early classical texts, as well as the Oracle’s status and power throughout the centuries— its workings, traditions, and influence, this paper is a succinct, tight overview of history. A good supplement for those who have a basic history about the Delphic Oracle (maybe because you’ve read the rest of this newsletter) but want to get a good, academic groundwork to serve as a starting point for further in-depth research.

“Delphi had to struggle for primacy against an Oracle, whose claim to be the most ancient was perhaps more convincing than her own; an Oracle, moreover, which claimed to derive its prophecies from Zeus itself— the great Oracle of Dodona, in Epirus to the far north.”

“The Prophet and the Necromancer: Women's Divination for Kings” - link

If you’re as unfamiliar with Biblical stories as I am, this paper is a nice, only slightly intimidating option to start with. Looking at the only two Bible stories with female diviners consulted (a prophet and a necromancer), this paper looks at the attitudes towards those professions, and the workings of authority, power, and gender within the Bible. In presenting these two tales of female diviners together the author tries to point out the differences between “prophecy” and “divination”, the latter being seen as magic at the time, and considered separate from the religious roots of “prophecy”.

“It was for a long time the norm for scholars to discuss "prophecy" and "divination" as if the two were separate and opposing categories. It is now increasingly recognized that prophecy is simply one type of divination.”

““A Woman is not Without Honour...”: The Prophetic Voice of Christa Wolf's 'Cassandra’” - link

My renewed interests in oracles and seers started with me reading Christa Wolf’s “Cassandra” (1983), a beautiful novel that seeks to ask the question… “Who was Cassandra before people wrote about her?”. The answer inevitably is thicker than blood, as Wolf examines gender, society, and constructs of war and the self through her version of Cassandra. This paper focuses more on the gender part, as well as Wolf’s investigation of the character of Cassandra, which makes for a quite compelling read.

“Prophets and poets make difficult stable companions and they share the ability to unsettle or subvert the norms of their societies. Because of this they are often silenced or killed. They both, in different ways, offer to the individual or community a two way 'glass' in which the individual or community then has to face the truth about themselves. One side of this glass acts as a mirror from which is reflected the breaking of communities; the injustice, the impoverishment, the godlessness, from which our laws and systems normally shield us. […]”

II. Seers, Oracles, Prophetesses

“Ecstasy. From the Greek ekstasis. Meaning not what you think. Meaning not euphoria or sexual climax or even happiness. Meaning literally: a state of displacement, of being driven out of one’s senses.”

by Jeffrey Eugenides, from “Middlesex” (2002)

Mankind has always sought to know. Or rather, mankind has always sought. Across time, place, and culture we have looked. We have tried to crouch and peer into the future, to gather signs, to know what is coming. Divination, prophecy, and fortune have tight holds on our imaginations simply because the mystical entrances us wildly, and we love to wonder… what if we really could translate the universe? What if we really could read the signs? What if there was rhyme, or reason, to why life swirls and swings the way it does?

Some version of divination has always existed throughout time. Mankind has always needed reassurance, and for this, they often sought out their gods of the times, or more likely, the mortal mouthpieces of those gods on earth. “The role of the prophet is to nurture and nourish, and to evoke a consciousness and perception alternative to that of the dominant culture around them” (Archive Source 3): these seers, oracles, and prophets1 were meant to offer perspective, as well as warnings or comfort. They were a mirror, ready to reflect people’s subconscious back to them, like an early, more mystical version of psychology, mixed with mediation. When the world at large was dense and impenetrable, these seers worked to break the fog down into smaller symbols that could be analysed, and explained. Often, this included certain mystical and ritualistic elements, that confirmed the seers divine authority to prophesize. In Viking Times, seeresses used “[a] staff, song, and special seat2” to get into a trance or ecstasy, from which they then related the will of the gods or the spirits. It is to be noted that these Viking oracles were largely, women.

Which brings us to the first of many red threads that we’ll follow today, the first to unravel: women, or rather, their presence throughout the history of divination. Interestingly enough, oracles and prophets were both most often men (Archive Source 3): or “The gender of a priest or priestess was normally the same as that of the divinity [they] served” (Archive Source 1). Yet the most notorious seers are, at large, women. However, it’s important to not conflate notoriety with authority. Rather, throughout history, when a seer, oracle or prophet is male, he gets a sort of authority straight from the divine and thus almost always immediately gets treated with legitimacy both by the texts they inhabit, and their circumstances. They might doubt whether or not people will believe them, but they don’t often see these anxieties come to fruition. Female seers, oracles or prophets are most often not framed as authority figures or leaders, but as witches. They’re notorious not out of respect, but out of fear and skepticism. Their legitimacy is a question, not a statement. Their vision is not necessarily treated equally to that of their male peers. It’s the female seers that end up on the stake, or beheaded, or executed. When a man gets a vision, it’s from God. When a woman gets them, she is in cahoots with the devil.

Historically speaking, this tracks. Witchcraft (whether “real” or not) was one of the most potent ways for women to seize power in historical times of oppression. In turn, fear of the witch has been instrumental in oppressing women, putting them back in their place. The notion of witchcraft was a tool for uprooting systems of power, and for re-affirming them. Women were thought to be weaker of disposition by virtue of their gender alone, and thus weaker to the devil’s manipulations. From this, concerns over women’s liaisons with magic (and by extension, the devil) could be framed as a need to protect their modesty, to banish lewdness, or to protect the helpless, all the while essentially stripping women of the power they fought to gain (see also: “Death and the Maiden: Sex and Execution 1421-1933” by Camille Nash).

We will discuss the Greek Oracle of Delphi more in-depth later, but she was by no stretch of the imagination the only oracle in Ancient Greece. In fact, there were probably hundreds of smaller, less organised oracles and seers at work, and they used the same methods of spirit possession— the difference? The Delphic Oracle was state-sanctioned, the others were not: “although magic was ubiquitous in the Greek and Roman worlds, it did not actually constitute anything like a pseudo- or unofficial religious cold with a coherent theology of its own.” (from “Witchcraft: a History” by P.G. Maxwell-Stuart, 2000). Unsanctioned forms of magic were still feared, and fear-mongering around the different forms of divination was particularly rampant.

It’s not hard to imagine why some might see divination as a malicious form of magic. Various forms of divination have always had an intense connection to mortality. Bataille would tell you it’s a form of eroticism: that we, as discontinuous beings (humans), are reaching for the continuous (universal truth) through the standard array of tools: namely sacrifice, mysticism, and religion. Blood, bones, bodily fluids. Where there is blood, there is life. In Ancient China, oracle bones from oxen and turtles would be cast by diviners to answer questions. The Mayans offered blood to the gods to divine the future or incur good will, and sometimes they even went as far as to sacrifice [human] life. And sure, the Ancient Greeks knew a fair bit about [human] sacrifice as well.

They mostly sacrificed oxen, goats, and sheep, but occasionally did venture into human sacrifice as well. Sacrifices to Zeus, like at the Lykaios festival, included several young boys. And there are more dramatic Greek myths involving human sacrifice as well. Take for example, Iphigenia, daughter of the Mycenaean king Agamemnon. She was lead to the altar, under the pretext that she was marrying the hero Achilles— while she was in reality led there to be sacrificed to Artemis so the Greeks could have favourable winds to sail to Troy: “this same Agamemnon had caused his own daughter, a young girl named Iphigenia, to be sacrificed on the altar of the goddess Artemis before his fleet crossed over. […] He had to sacrifice her, he said. That was not what I wanted to hear: but of course murderers and butchers do not know words like ‘murder’ and ‘butcher’.” (From Christa Wolf’s “Cassandra”, 1983). In some versions, Iphigenia is swapped with a deer at the last moment:

“The priest seized the knife and offered a prayer as he looked for a place to plunge the knife's point. […] The priest cried out. The army echoed his cry, and then they saw the miracle, impossible to believe even as it happened before their eyes. There on the ground lay a deer, gasping for breath. She was a full-grown deer, beautiful, and the altar of the goddess was dripping with her blood.”

Description of the sacrifice, from Euripides’ “Iphigenia in Aulis” (405 BCE)

It is interesting then, that perhaps one of our most famous seers, the prophetess Cassandra, gets that very power to see turned against her. In Greek mythology, Cassandra was a Trojan princess who ached for the gift of prophecy, and decided to seek out Apollo and become a priestess at his temple to get it. Fine, in some versions she didn’t necessarily desire the gift of prophecy, but I’m casting a very ambitious Cassandra here. Stay with me. This is where the story diverges: in the most common telling, Apollo, in order to win her love, gave Cassandra her foresight after she promised him certain favours. When she then went back on her word, Apollo added the stipulation that she would utter the truth, but never be believed. Now, in a second version, Apollo gave Cassandra her gifts without her needing to make any promises, and then when she did not return his desires naturally, he added the curse.

“Apollo, the god of the seers. Who knew what I ardently desired: the gift of prophecy, and conferred it on me with a casual gesture which I did not dare to feel was disappointing; whereupon he approached me as a man. I believed that it was only due to my awful terror that he transformed himself into a wolf surrounded by mice and spat furiously into my mouth when he was unable to overpower me.”

By Christa Wolf, from “Cassandra” (1983, p. 24-25)

Either way, an immensely tragic figure is formed: a woman who can see all the horrible things about to happen to her fellow Trojans clear as day, but can do nothing but watch as nobody believes nor heeds her warnings. She serves as a priestess at Apollo’s temple, people come to tell her of their dreams, in want of explanation, in need of comfort. But who will comfort Cassandra? The great Trojan war waits to unfold and Cassandra can do nothing but wait for the other shoe to drop, the exact same way she knows it will. She laments Apollo: “Apollo, Apollo! / God of all ways, but only Death's to me, / Once and again, O thou, Destroyer named, / Thou hast destroyed me, thou, my love of old!”. (Aeschylus, “Agamemnon” 5th century BCE). Her story ends with her capture by the Greeks, having been raped by Ajax the Lesser in Athena’s Temple, and the execution of her and her twin children. Tragic until the very last line of verse.

As we’ve mentioned before, oracles were quite common in Ancient Greece, as part of a larger religious ecosystem of temples, priestesses, and worship. Perhaps most famous of all, though, is Pythia, or the Oracle of Delphi, who served the god Apollo. Now, the Greeks believed that the oracles were a sort gateway to the gods, or their mouthpiece. People of all walks of life and ranks would seek out the oracle for guidance, and the Delphic Oracle in particular was held in exceptionally high regard for a period of time, in both a religious and political context. Of course, the prophecies uttered by any oracle were more often than not, vague, and open to interpretation. That is not something that immediately has to be met with skepticism, after all, prophecies are vague, visions fleeting, and symbols often contradictory: our very own dear white lily represents both death and rebirth, and is a flower used both in weddings and funerals. Mixed signals are everywhere.

And so, the Delphic Oracle would scream out her incoherent and ecstatic reply, which would then be translated and re-arranged into clearer, but still quite manic and riddling epic verse by her Prophetes or chief priest[es]s. These prophecies can be quite beautiful in their own way. Deeply symbolic, filled with rich imagery and subtext. My two favourites are:

“Now your statues are standing and pouring sweat. They shiver with dread. The black blood drips from the highest rooftops. They have seen the necessity of evil. Get out, get out of my sanctum and drown your spirits in woe.”

Oracle of Delphi, prophecy from 480 BCE

“Tell the king; the fair wrought house has fallen. No shelter has Apollo, nor sacred laurel leaves. The fountains are now silent; the voice is stilled. It is finished.”

The Oracle of Delpi’s final prophecy, 362 AD

Lass June, I had a dream in which I was fate itself. Or rather, a weaver of it. Stay with me here. In this sticky sweet dream reality, if I zoned out ever so slightly, I could see millions of deep red strings, suspended before me in mid-air, like a cut-out into another dimension. When I closed my eyes, I could reach in and feel the yarn on my fingertips, the threads grazing my wrists. And I could look. Look at all that had happened, all the things that were happening, all the things that could happen. I could take each string and follow it to its beginning, or its end. But looking was a conscious action, and a time-consuming one at that. Fate’s gaze was exhausting and consumptive. Nothing was ever set in stone, and every event had innumerable possible consequences— things were always shifting. In my dream, I started to become more and more disconnected from my life, my friends, my reality, the more time I spent gazing into the threads. And instead of some mysterious unexplained forces, it was me who bore the weight of my friends’ ire when something ill befell them. Not understanding that sometimes bad things have to happen to avoid worse things. It was a profoundly alienating experience, and the dream evidently stuck with me for some time.

I don’t know why I’m telling you about it.

My red strings do have some sort of place in history: an old Chinese proverb tells of a red string connecting soulmates, pinky to pinky—“An invisible red thread connects those who are destined to meet, regardless of time, place, or circumstance. The thread may stretch or tangle but will never break.” Of course, I knew this before I dreamed of my own impenetrable dimension of red yarn. But the idea of “weaving” fate itself is also an ancient concept on its own, sans red strings. The Roman fates or Moirai were also thought of as spinners. Norse mythology believed in the Norns, or three beings that “weave” the grandiose tapestry of fate under the World Tree (Yggdrasil): the tree that connects the three “layers” of the world— Asgard, realm of the gods. Midgard or earth, and Hel, which would be the Norse mythology equivalent of an underworld. Translations of the three Norns’ names Urd, Verdandi, and Skuld vary wildly, but most commonly they are referred to as some variation of Fated, Becoming & Must-Be3. Simplified, there is one Norn who is concerned with the threads that go into yours when you are born. Your circumstances, your background, and the unchangeable facts of your existence. Then Verdandi is the one holding up the threads, examining them. She is the one seeing the present moment, and all the opportunities and connections that could possibly stem from it. Finally, Skuld is the one that cuts the threads. Death, if you will. The unknowable (Irisanya Moon, “the Norns: Weavers of Fate and Magic”, 2022).

It would be a shame to write about all sorts of seers and leave out the one and only Nostradamus, so I shall briefly touch on him as well for the sake of completionism. Nostradamus was a prolific French seer, astrologer, apothecary, and physician, at one point working in service of Catherine de Medici at the French court. He’s most well known for his numerous prophecies about world events, spanning hundreds of years and even centuries into the future. Even to this day, there are people that credit him with having accurately predicted many world events, and though there are plenty of skeptics, his visions for the future in particular have been adopted by the masses in a very light-hearted, almost kitsch way. Meaning my [Dutch] grandma had a book of his translated predictions for the years 1992-2001 on her shelf. Even more than most other seers, his visions are brief, vaguely worded, and wrapped in nearly-indecipherable amounts of world-play, reference, and symbolism. How one interprets them is entirely up to the translation they work with. Long story short, people are quick to point to Nostradamus as a fraud. He does not get afforded the aforementioned male seer privileges. Perhaps because he was also associated with witchcraft at the time through his apothecary pursuits.

But still, there’s people out there in today’s day and age who think that Nostradamus did mysteriously get some things right. In the midst of our hyper-individualistic, extremely skeptical [Western] culture, there’s people who make room for a little magic— some in more healthy ways than others, of course. There’s always people who take it too far.

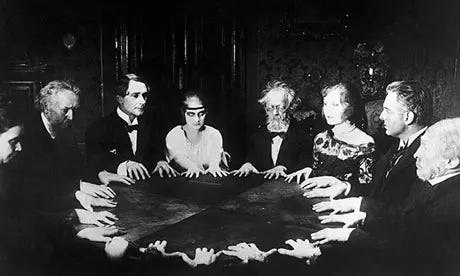

Mediumship and spiritualism had its last big peak over in the Victorian times, when seances, ghost stories and fortune tellers made a lot of people very, very rich. Spiritualism was a philosophy of its own: a curious, non-judgemental, almost scientific approach to the spirit world. You know, parlour spirit boards and the like. Gathering around for a seance after some drinks. Recounting ghostly tales by the fire. Many figures, like our familiar Swedenborg (who popped up in Issue 04) made entire careers out of the ability to communicate with some sort of an afterlife. Many more mediums rose to fame, only to be subsequently unmasked as frauds. Our willingness to speak to the dead has understandably deteriorated with time— back in the Victorian times, people thought the dead would have no greater wish than to reach out to the living, and the idea of contacting an “evil” spirit or a spirit impersonating another spirit was mostly unthought of. You can thank movies like “the Exorcist” (1973) and “the Conjuring” (2013) for unlearning those cultural ideas about largely kind-hearted spectres. But parts of spiritualism’s “rituals” and wider divination practices are still alive and kicking: tarot, witchcraft, and paganism certainly seem to be on the rise in the past decade or so.

It’s quite interesting to me that we as a modern society have widely lost touch with our instincts for noticing patterns, for seeking guidance, for finding significance in seemingly insignificant symbols. Perhaps with the decline of religion we have lost our willingness to see individual symbols as signs, as part of a greater whole. And yet, patterns and data hold a great position of power in the business side of our world: just think of all the data analysts, algorithms, and AI that have a part in running the stock market, for example. In many ways, patterns and magic still have their metaphorical claws in us. Personally, I’m no stranger to a wide variety of divination methods. I’ve laid out an insurmountable amount of tarot spreads, poured over tea leaves, and I’m certainly no stranger to a little dream prophecy here and there. I love all the whimsy to be found in life’s symbolism and connections, the way you can sometimes almost feel the threads of fate pulling you places.

And prophecies, seers, and fortune tellers are of course still numerous across [pop] culture. We never really stop being fascinated by the idea of the Chosen One, of the hero’s journey. Prophecies are extremely common plot devices in the fantasy and science fiction genre- stories that also love the Chosen One / hero’s journey constructs- as well as appearing throughout plenty more history and literature. Caesar was warned about the Ides of March by a soothsayer (seer). The character of Nostradamus in the CW’s “Reign” is meant to be a fictionalised foil to the real one. There’s Professor Trelawney in Harry Potter, the witches in Macbeth, the red lady Melisandre in the ongoing “A Song of Ice and Fire” books, the Oracle in the Matrix movies, and one-off character Cassie in “Buffy the Vampire Slayer”, just to name a few. But let me leave you with this last prophecy, taken from Game of Thrones, whose poetry I think is particularly salient and shimmering for an ending note:

“From my blood, come the prince that was promised, and his shall be the song of ice and fire.” & “After a long summer when the stars bleed and the cold breath of darkness falls heavy on the world / He shall be born again amidst smoke and salt […]”

Addendum from spin-off show “House of the Dragon” (2022-), and part of the original prophecy from the books

III. Museum Recap: May

“'I have led a toothless life,' he thought. 'A toothless life. I have never bitten into anything. I was waiting. I was reserving myself for later on--and I have just noticed that my teeth have gone. What's to be done?'“

by Jean-Paul Sartre, from “the Age of Reason” (1945)

May has been a month that stretched time, at least for me. So much did I see, so much did I do. It was equally invigorating and exhausting. Recharging, but draining. But then again, spring often has that quality. Something about the rebirth of nature will do that to one’s internal clock. All the flowers blooming up through the soil. Or perhaps the fairies are messing with us all, moving the sun back while we sleep so that the days and nights drag on and on and on.

As usual, I wish to talk of some art here in this section, specifically some exhibitions in London that saw this month and whole-heartedly recommend. With my entire being. It’s not often that the exhibitions and events I attend are still on-going when it gets to the newsletter, so today is a rarity! What a joy! Regardless, I wish to teasingly dangle some art-shaped temptations in front of your dear face like holding up a light for the moths to swarm to. Yes, you are the moth in this scenario. And a very lovely one at that. Now, let me get to the dangling part, please.

Besides heading down to the Royal Academy to see Leighton’s “Flaming June” (1895) at my visiting friend’s behest (on until January 2025), we also went to Kenwood House! A little bit of a full circle moment, as we had intended to stop by when she was staying with me last May, and never quite ended up making it. Fate works in mysterious ways, doesn’t it? If you’re looking for something to do on a day off, I do recommend a visit, even if just to take in the pretty artworks and get some sumptuous home decor inspiration, and if the weather permits it, to go for a stroll through Hampstead Heath afterwards. There’s enough green to positively overwhelm the senses.

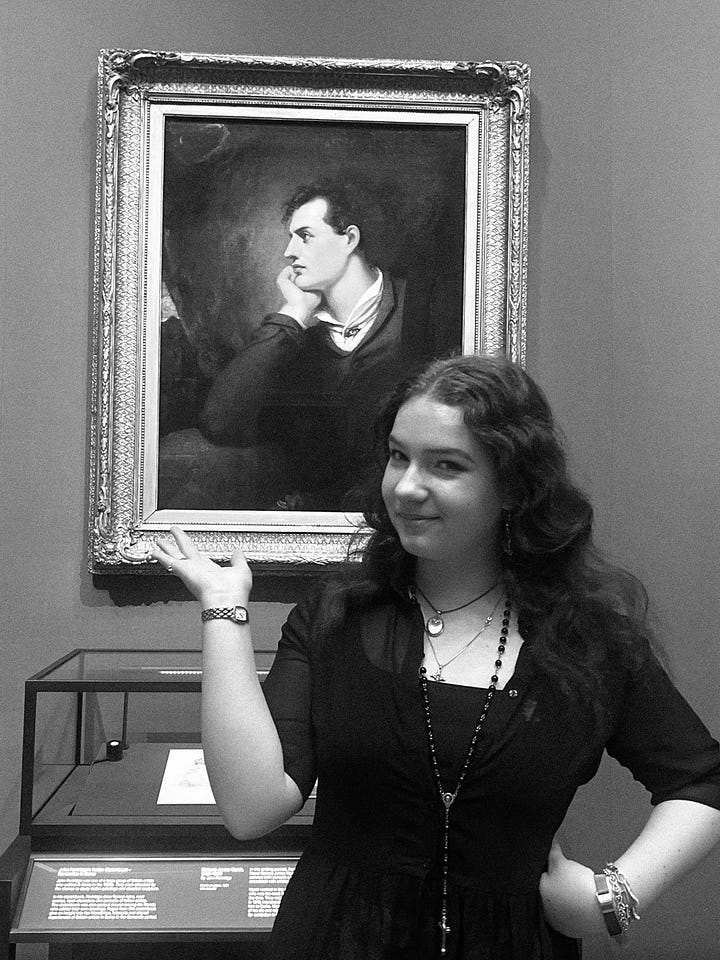

Now, if you were only going to take one recommendation from this section (But why on earth would you do that?), I beg of you to have it be this one. “Portraits to Dream In” is on at the National Portrait Gallery until June 16th and is so divine and delightful that it made me spiral into remarking that everything was “beautiful, beautiful, beautiful”. I might even have gotten a bit teary-eyed… but that’s all just gossip, speculation. Don’t go telling everybody that yours truly got overwhelmed by beauty once more! They wouldn’t be surprised by it.

The exhibition presents the work of two photographers side by side: Julia Margaret Cameron from the 1860s, and Francesca Woodman from the 1970s, drawing parallels between their work across time. There’s not a photograph in this wonderful exhibition that isn’t brimming with dreamy, ethereal, pre-Raphaelite, tragic, Romantic goodness. It’s just so incredibly up my alley, like I dreamed it myself. And you’ll be pleased to find that for once I don’t have to complain about the length of the exhibition! It’s a much more manageable, and affordable experience, which only makes the whole thing sweeter and sweeter. I do intend to stop by once or twice more.

After my friend left again, I also went to see “Sargent and Fashion” at the Tate Britain (on until July 7th) with yet another friend (it was a very social month!), and that was quite unexpectedly delightful as well. Sorry if I sound one-note, dear, but I don’t ever share anything not quite up to par with you. Even if I always ramble on I do believe space is somewhat precious in these letters of mine. Anyways, I was not too familiar with Sargent’s work (sans “Madame X”) before this, but I must share that I’ve been converted to a fan. Sargent’s portraits have a very dreamy, almost impressionistic style to them. Presented together they are quite literally a look into a long-gone world and strictly segregated social class, obsessed with styling and self-image:

“Sargent and his sitters thought carefully about the clothes that he would paint them in, the messages their choices would send, and how well particular outfits would translate to paint. The rapport between fashion and painting was well understood at this time: as one French critic noted, ‘there is now a class who dress after pictures, and when they buy a gown ask ‘ will it paint?’”

Exhibition text, “Sargent and Fashion”, Tate Britain (2024)

And that already wraps up this section, my love. I suppose you are waiting to see if I’ll remark on my goals for the year, as is customary. So, here we go: my reading goal is currently sitting at 19 out of 52 books, 2 books behind schedule, but we are gaining momentum again! Really, nothing would bring me more joy than to report next month that I’ve made it back on track. Don’t worry though, my reading speed or lack thereof is definitely not for lack of reading material. My shelves are plenty stocked, to an almost intimidating extent. Alas, for now we are behind. Check back in June.

As for my movie goal, it is to be expected that we are running ahead of the charge on that one, with 32 out of 52 new films watched. Makes sense, considering a movie is a little less time investment than you put into the average book. Still, maybe I should redirect some of this energy expenditure into books for the next month or so. Much to ponder on, I fear.

Now, you probably are also aching for some quick-fire recommendations, and I do so love recommending things, so here is just the tiniest taste of what I adored in the past month. In terms of books, obviously I would have to start with Christa Wolf’s “Cassandra” (1983), which was, believe it or not, my very first foray into Greek mythology. Safe to say I’m hooked, and also the number one Achilles hater in the world. For now. Another book I enjoyed was Vladimir Nabokov’s “Lolita” (1955)— I feel like I have to make some sort of disclaimer here that just because you enjoy a work does not mean you agree with it. There are many enjoyable parts of “Lolita” far beyond its controversial subject matter: the glittering prose, the hazy dream of an American summer it often conjures up (an illusion), and the inventions of Nabokov, who writes his unreliable narrator Humbert Humbert as if he is seducing you through language, through the recounted story. Finally, I’ll also recommend you Louise Glück’s “Averno” (2006). A very short poetry bundle, worth it, in my opinion, for the poem “Persephone the Wanderer” alone. It’s one of my most cherished favourites.

I was planning to stash away my film recommendations in my pocket for a good while longer, but the sunnier weather has changed my mind. I feel more giving than usual, don’t mind my twists and turns. Considering that I love everything that comes in threes, of course I have to give you a three-fold of film recommendations, starting with “Lolita” (1997). Same footnotes as for the book here, and I do recommend you read it before you see it. This is a disgusting, pathetic, but very beautiful film. Visually, it’s the ideal dream of summer. Red gingham, hazy boredom, and the ripest fruits. If you can ward off your visceral disgust at the story for long enough, you might get some more than enjoyable visuals out of it. Next, for the ones inspired by this newsletter, I’d recommend witchy cult classic film “Practical Magic” (1998). It’s sexy, it’s wholesome, it’s beyond crazy. Imagine a story of sisterhood, with witchcraft, romance, and a side of spirit possession. That’s what you’re in for, and it’s gloriously tonally all over the place. In a good way. Finally, for all my fellow “Death and the Maiden” trope enthusiasts, do hunt down a copy of “Panna a Netvor” (1978, aka “The Virgin and the Monster” aka “Beauty and the Beast”). It’s a lovingly tender, Gothic adaptation of the classic tale, and one that has stolen my heart. Highly recommended.

“I like it dark. The dark is comforting to me.”

by Tennessee Williams, from “A Streetcar Named Desire” (1947)

And here we are again, at the end of yet another string of fate. We’ve weaved and spun and intertwined a plethora of deep red threads, all to get right here, to this very newsletter, and its unfortunate end. At least for today. The Norns are raising their scissors in the golden dawn, telling me to hurry up. It’s so gauche to overstay one’s welcome.

I wish I could tell you my plans for June after this whirlwind May were to settle down a bit, but that would be a lie— and I’ve promised not to lie to you today. No, this June I’m headed for both France (Paris), and Switzerland. Shocking if you know me, considering I’m usually way too fond of my luxurious routine to venture far from home. Must be something new in the air. There’s just so many odd things happening all at once. It’s dizzying and comforting and transformational. Though I am usually not a fan of the warmer months, I must say my grand fatalism has not yet set in this time of year. Maybe it won’t show up at all. Wishful thinking, sure, but who doesn’t like to make a wish every now and then?

My love, my dearest muse, my fellow White Lily Society member, it’s for you that I write. Thank you for once more being receptive to all my ramblings, all my weavings, all my conjurings. The wonder and whimsy of the world is an inexhaustible well with you all at my side. I hope you have the prettiest June one could bear to dream up. Soon, it will be Midsummer. Don’t forget to eat only the plumpest strawberries, to never follow the wisps in the forest, and to collect seven different flowers to put under your pillow, so you can have the most enlightening dreams of all. Fairytales couldn’t ever compare.

“And then one fairy night, May became June”

by F. Scott Fitzgerald, from “the Beautiful and the Damned” (1922)

Until my next letter,

x Sabrina Angelina, the White Lily Society

Currently reading: “Black Venus” by Angela Carter // Most recent read: “Bluets” by Maggie Nelson

White Lily Society links // Sabrina Angelina links

It was prophesied that you would subscribe to the White Lily Society… Will you let the threads of fate be wrong? Will you scorn the Norns? Or will you join us, and become a martyr of deliciousness, as you’ve always been meant to be? Come on, I know you want to.

The term at large here is “soothsayers”, however for sake of convenience oracle / seer, and prophet will be used mostly interchangeably (keeping in mind that prophets are usually religious in nature)

Source: National Museum of Denmark. Note that the Oracle of Delphi also used a special seat, or a tripod (see Archive Source 3)

Variations I’ve seen include “Fate, being, necessity”. Note that this does not necessarily represent the traditional “Past, present, future” set-up