17. Swan Song

For a delicate and Romantic soul.

“December’s immaculate coldness feels warm. December feels like blood.”

by Zinaida Gippius, date unknown

If, by any chance, you are looking for a proper soundscape to read this newsletter and let it fully soak in (with a cup of tea, and candlelight, and maybe a sweet treat of sorts), then may I recommend you this playlist I made especially for you full of haunting piano songs, ambient atmosphere, and completely instrumental tunes— perfect for wandering dark hallways at night, or sitting down with a letter from a dear friend.

01/12/2024, London, UK

My dear,

December is upon us now with frozen recognition. A tenderness extracted from ice. As always, I am a sweet angel girl as the months get colder. I draw nearer towards wonder, equally sensitive and romantic. But I am also, I admit begrudgingly, a girl with a worryingly high screen-time. Two things can be true at once. Nevertheless, I don’t really notice falsehoods. I find myself worshipping them often if they’re beautiful and harmless enough. Sullen sweet.

When the air’s embrace is colder than ever, the theatrics of this connecting season are enough to last me through the grey, through the uncanny warmth of the holidays, the quiet desolation when days are shrouded in darkness1. The drama of taking off your gloves, the wonder of being able to see your breath, the warmth and cold ebbing and flowing throughout the days. And every time I wear my huge vintage fur coat I’m humorously reminded of Lord Byron going for runs in his one(s). Suffering made fashionable, I suppose. There are much worse ways to go about it. It’s the season’s spirit to lift average pain into martyrdom.

But now, I am looking towards the stars to find a spot for you, my dear. I methodically spread the deck in front of me, like a fan, or half of the moon, or a sickle. My hands are tied with red string, my fingers caress the cards. What is in store for us today? The luck of the draw goes as follows: the lovers, the three of swords, the five of cups. Well, there is romance and then there is tragedy. Beauty and pain… the Intersection of Love and Violence(tm). Our letter today lives in a world of original sin in which the sin is to extend the hand of love outside of yourself, and the just punishment for the crime is a tragic end. Thus, the title of the letter— fret not, there will be more after this (yes, that is a threat).

New, new, new. What is in demand is always what is new. No need to be star-crossed, my dear. The heavens are honest and fair. There is not much for me to put on display here, except for a single submission, a review of Metamorphika’s The Coven: An Invocation of Pagan Rituals (2024): all about witchcraft, paganism, and folk spirituality, this evocative and succinct submission is brief but precise. And it doesn’t hurt to look at these gorgeous images of the art on display either! But quick, quick, hurry on now. The journey ahead of us is perilous, fraught with twists and turns, but caught up in love. Head on now, my dear. Don’t look behind you, for you may not like what you see, or don’t see.

Into the lion’s den we go. To face the wolf. Excuse the mixing of animal metaphors. Just place your one foot in front of the other.

I. Archive Sources

"Strengthen me with raisins, refresh me with apples, for I am faint with love."

from the Bible, Song of Songs 2: 5, New International Version

The cards have spoken, and an anthology of tragedy is on the menu for today’s letter! A particularly succulent selection, if I may flatter myself, and I will. But if you want to deepen the melancholy, enhance the bittersweet sting of it all, then allow me to suggest some further reading. These three papers are, as always, selected to maximise the impact. Go on, my dear, allow yourself to feel the depths of the forbidden, the tragic, the doomed, and get a little sampler of what’s to come in the progress. Or use them as a supplement, a sacrament, a dessert. The choice is entirely yours, and it always will be. I’m just the messenger.

“Keats against Dante: The Sonnet on Paolo and Francesca” - link

Translation is a crucial part in how we take up a large chunk of the world’s many myths, legends, and stories, and the story of Paolo and Francesca from Dante’s “Inferno” (ca. 1321) is no different. Dante’s original tale is very much one of “passion in conflict with morality”, of adultery and sin, and yet the Romantics of the 18th century absolutely adored the tale. This paper touches on the uniqueness of both Dante’s Canto V, but also the oddities in Keats’ short poem inspired by it. Bringing into it paganism, mythology, as well as Keats’ own philosophies (like that of “negative capability”), not to mention the Romantic movement’s notoriously hard feelings surrounding the concept of matrimony— it is no wonder that a passage of forbidden romance against the constraints of marriage gripped them so!

“Thus Cary tries to make the story of Paolo and Francesca into a romantic tragedy, so that we will simply pity the protagonists, whereas the original is a case-study of false perception and misplaced sympathy. For instance, ‘cotanto amante’ literally means ‘such a lover.’ Dante leaves it up to us to decide what kind of lover Paolo is. But Cary answers the question in Paolo's favor, rendering the phrase: ‘by one so deep in love’”

“Tristan and Isolde, the Consummate Insiders: Relations of Love and Power in Gottfried von Straßburg's ‘Tristan’” - link

Reading into another tale we will be more intimately familiar with down the line, this paper looks at the friction between love and power within Gottfried von Strassburg’s “Tristan” (ca. 1210), and especially the nuances between the lovers alternating as insiders, and as outsiders. It is often [mis]understood that Tristan and Isolde’s illicit affair is what frays Marke’s court, but that would be far too simple of an explanation. The paper alludes that at many different points in the story their illicit affair switches from being beneficial to being harmful for the court, and every shade in between. To simply call love the undoing power is fraud.

“The fundamental difference from other Arthurian romances is that the acquisition of lón in Gottfried's poem- Tristan's "winning" of Isolde- does not lead to closure, but rather itself constitutes a threat to social integrity: Tristan does not obtain his own queen as a consequence of his initial efforts, but rather the queen of another. The resulting threat to court society is twofold: 1) Tristan's union with Isolde undermines the sacrament of marriage and, perhaps more significantly, 2) it usurps for Tristan prerogatives legally and customarily belonging to the King of Cornwall and England”

“Descent to the Underworld in Ovid's Metamorphoses” - link

Journeys into the underworld are so pervasive in Greek mythology that there is a specific word just for them: “catabasis”. This paper is short and succinct, looking briefly at the catabasis of Orpheus, Hercules, Aeneas, and Aesculapius. As well as examining the meaning of myth’s usage of catabasis as an inspiring force for the reader. For Orpheus, it is love that wins, as well as undoes. His joy lies in getting to die, but for the other wanderers, their descent leads them to chances to aspire beyond mortality and “win their way to Elysium”. Either way, what bliss.

“In the remainder of the song, Orpheus acknowledges the power of the Underworld and its gods, to whom all mortals must finally come. Even Eurydice must be given up again, Orpheus knows, but he begs to be granted usus of her until that time, as a gift. He closes with a refusal, unique among accounts of descent to the Underworld, a refusal to return to the world of the living and resume his life. Love is victorious over the fear of death, […]”

II. Doomed Romances

“These violent delights have violent ends And in their triumph die, like fire and powder, Which, as they kiss, consume.”

by William Shakespeare, from “Romeo and Juliet” (1597)

When it comes to these dear letters of mine, I believe the classic tragic romance needs little introduction. Whether you’ve been around for one, or four, or all of them, there is always at least a trace amount of both romance and tragedy involved: that’s what the Intersection of Love and Violence(tm) means. Some people, like me, love to swoon at them, and some (more pragmatic) people enjoy ridiculing them, but there is nary a person on this planet of ours that cannot recall at least one such story. “Love is the great bringer-together: all writers write love-stories, all readers read them.” (from “The Penguin Book of Romantic Poetry”, p40)

I’ve always believed in my personal need to stockpile such tales, because I enjoy recounting them, indulging in them, savouring them. And the world has offered no shortage of supply in return. Beyond the good notes of Shakespeare’s “Romeo and Juliet” (1597)— perhaps the most well-known star-crossed lovers (they quite literally coined the phrase!)—, there are endlessly fantastic doomed romances to be picked up on in literature, myth, and even real history. Any appetite for the tragic need not remain unquenched.

Here today, for your passing fancy, I have selected a few of my absolute favourites. Some I’ve known a long while, and some I have only known shallowly, prompting further research. Though they are all different and the same in their own way, I’ll safely spoil the endings of all of them in a single breath now: one, or both of the lovers, are always destined for Death himself. You have been warned. Read on at your own risk. Beyond this point there is little hope for happy endings.

“Let me set the scene / Two lovers ripped right at the seams”

by Kacey Musgraves, from a song called “Star-crossed” (2021)

II.I Isabella and Lorenzo: Botanical and Doomed

“Fair Isabel, poor simple Isabel!

Lorenzo, a young palmer in Love’s eye!

They could not in the self-same mansion dwell

Without some stir of heart, some malady;

They could not sit at meals but feel how well

It soothed each to be the other by;

They could not, sure, beneath the same roof sleep

But to each other dream, and nightly weep.”

by John Keats, from “Isabella, or the Pot of Basil” (1820)

We set the scene, the thick velvet of our theatre’s curtains ascending without fault. Italy appears before us. As in all of the following tales, names and details shift with every fragmented version we pick up on. Your story might be different from mine, your mileage may vary. The Italy we find ourselves in is ravaged and desolate, on the brink of ruins brought on by the Black Plague and the mass death that followed it. We settle in a household of three brothers, a sister, and no parental figure. Uncommonly, though she is of the proper age and willing, Isabella’s2 brothers have failed to find her a husband in the wake of their father’s death. So where love is absent in the ways that are expected of her (parental love, marital love), she instead finds her own.

Love takes the shape of Lorenzo, a worker at Isabella’s brothers’ warehouse. He’s a respectable young man, leading the various workers with a manner that is both amiable and reliable, and Isabella’s thoughts languorously settle on all that which she finds pleasing in him. Lorenzo, noticing the young maiden’s attention, soon returns it. The two develop an affair at whirlwind pace that is both romantic, lustful, and passionate. But it was not meant to last. One night, as Isabella sneaks out to find Lorenzo in the depths of night, she is spotted by her eldest brother, who quickly brings word to the others. Of course, such an offence to virtue as hers would bring shame upon the whole family at large, and so the brothers vow to handle the sin under their roof in secrecy.

They scheme to take Lorenzo exceedingly far into town, under some guise or another, perhaps an innocent business trip, and when they get to a place they deem lonely and desolate enough, the cowards corner their poor employee and kill him, burying him in a shallow grave. No matter what poor excuse they give a distressed Isabella for Lorenzo’s absence in the next few weeks, she is relentless in her fervour, praying and weeping for him to return. One night, as she has cried herself to sleep, Lorenzo appears to her in a dream, informing her of the treachery against him down to the detail of the burial plot itself.

Isabella, touched by horror, ventures out the very next morning to see if her dream had been true, and finds the grave of her love, where his body lays miraculously untouched by decay, confirming his identity beyond any doubt. Grief-stricken and delirious, she decides to give her true love the only proper burial she can give him, and seeing as she can’t take his whole body in her arms to drag him across town, she takes out a knife and a handkerchief, and begins to carefully saw his head off as best as she can.

Back home, she decides to keep Lorenzo’s remains as close to her as possible. After she impresses his face with a thousand sorrowful kisses, she finally plants his head in the soil of a beloved pot of basil, and waters it daily with her own tears. Not a minute passes without her yearning to be close to it, to feel, in some way, the presence of her beloved Lorenzo. She and the pot of basil are inseparable, connected by misery to such a point that even her brothers take notice of it. Even in sickness, Isabella wishes only to have the pot with her, and this prompts her brothers to dig around one night, until they pull up a curl they correctly identify as Lorenzo’s. Panicked by what they perceive as a smoking gun, they go to bury the head, taking the pot away from Isabella for good, who in her ceaseless heartbreak, dies from it.

“The damsel, ceasing never from lamenting and still demanding her pot, died, weeping; and so her ill-fortuned love had end.”

by Giovanni Boccaccio, from “the Decameron” (1349)

II.II Paolo and Francesca: Infernal and Doomed

“If someone asked me at the end / I'd tell them, ‘Put me back in it’ / I would do it again / If I could hold you for a minute / I'd go through it again”

by Hozier, from a song called “Francesca” (2023)

Here is the story of a couple which we meet in death, rather than in life. Francesca da Rimini is another Italian woman trapped in a loveless existence, bound within the confines of a political marriage to the crippled Giovanni Matalesta. But instead of resigning to the misfortune of her circumstances, she gets involved in a tempestuous affair with Giovanni’s able-bodied and married brother, Paolo. Spurred on by her love of romantic literature and poetry, and perhaps even the idea of romance itself, the two inch ever closer and closer to sin.

It is fitting then that it is ultimately another literary couple’s passion that ignites Paolo and Francesca’s. As they are reading the story of Guinevere and Lancelot from Arthurian legend (another doomed, adulterous, forbidden affair), one of them opening the pages and another leaning in to read, their physical proximity overwhelms them and the two share a single kiss.

"One day we read together, for pure joy how Lancelot was taken in Love's palm. We were alone. We knew no suspicion. Time after time, the words we read would lift our eyes and drain all colour from our faces. A single point, however, vanquished us. For at last we read the longed-for smile of Guinevere - at last her lover kissed - he, who from me will never now depart touched his kiss, trembling to my open mouth"

by Dante, from “Inferno” (1321), lines 127-136

Of course, the pair are seen, and condemned to death. Actually, it is Francesca’s husband Giovanni who, in a fit of jealous rage, kills the couple. It is in hell that we are told their tale, as Dante writes in his journey, the “Inferno” (1321) Canto V. And though they appear in the circle of hell reserved for the lustful, Dante’s depiction of a fictionalised Francesca recounts the story with a certain detachment and lack of agency— notice also that it is her speaking, and never Paolo—, as if the literature itself is to blame, and exaggeratedly enflamed the passion and lust in the lovers. There is not remorse, nor personal responsibility in her reframing of her actions, and there is no mention of the actual sin of adultery.

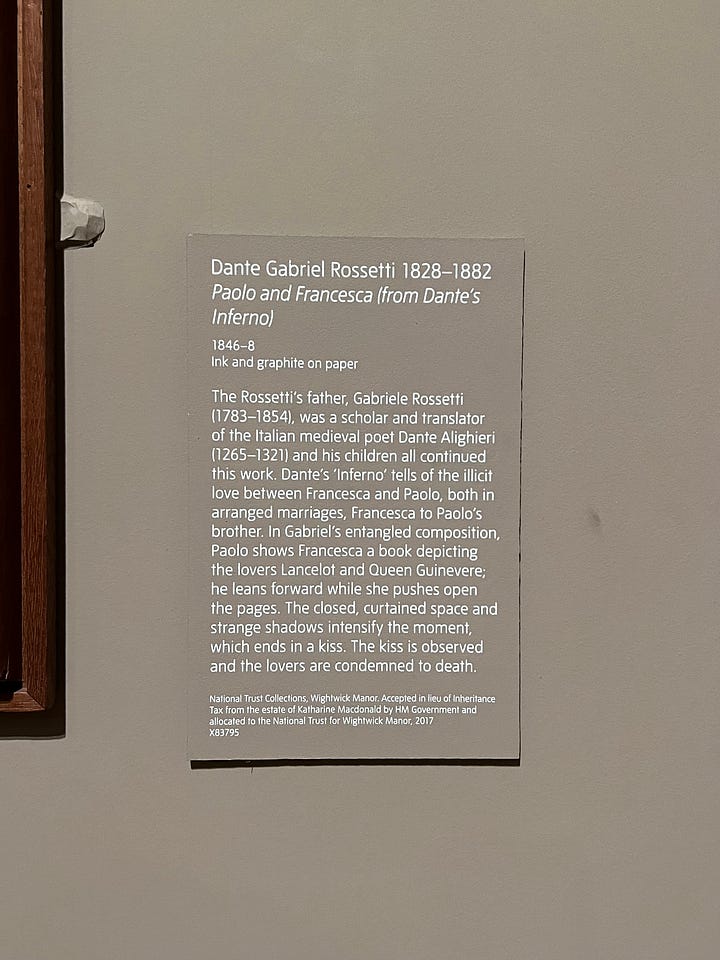

Dante did not intend for us to take their story to heart as a tale of romance, and yet the Romantic poets of the 18th century carried a near-extreme torch of sympathy for it. Lord Byron almost “swoon[ed] to death with sympathetic thought” (Archive Source 1), used snippets of Francesca’s speech for his poem “the Corsair” (1814), and planned to write a tragedy based on the lovers. Dante Gabriel Rossetti did several sketches and paintings depicting their fatal kiss. Leigh Hunt wrote a lengthy poem, “the Story of Rimini” (1816). And even Keats wrote a poem inspired by the tale of Paolo and Francesca, which I pinkie promise we shall return to later when its impact is all the greater. For now, lets add on one of their contemporaries’ thoughts of the tale’s resonance:

“Sin is the supreme pathos of this tragedy because the conflict which it engenders is not external to the lovers, but takes place in their very souls— and without conflict, love is not tragedy but Arcadian prose, pastoral poetry […].”

from Archive Source 1, from “Francesca da Rimnini secondo i critici e secondo l'arte” (1869) by Francesco de Sanctis

II.III Tristan and Iseolde: Chivalrous and Doomed

“Apart the lovers could neither live nor die, for it was life and death together;”

by Joseph Bédier, from “The Romance of Tristan and Iseult” (1170)

I realise now in writing this that we are jumping all over time and space for our tragedy tourism. Sorry to dizzy you, my dear. Anyway, we arrive in England… pre-England. Before the unification of the individual kingdoms, when there was still Wessex and Cornwall, and war with the Irish. In the original tale by Gottfried von Strassburg (ca. 12th century), it is in this environment that the brave and skilled young Cornish warrior Tristan comes of age. After he finds his way to the court of King Marke, he is revealed to be his nephew, and quickly begins to curry favour with the noble king, getting knighted for his efforts.

But the Irish king seeks to keep the English oppressed and disorganised, sending his brother, the notorious Irish knight and warlord, Morold (also known as Morholt), to collect tribute. Valiant Tristan challenges him to a duel, and of course he wins. He is the brave hero of this story after all. But he doesn’t win without any challenge, as the poison on Morold’s sword incapacitates him to such an extend that he is forced to travel to Ireland to find a cure.

Enter Isolde3 [the Fair], the daughter of the Irish king. As Tristan schemes to get healed by the Irish queen, also named Isolde [the Wise], he meets the younger Isolde in the process and of course they immediately have eyes for each other. Young, beautiful, accomplished people need little else for a crush. They just need a small spark to start a big fire. Restored and rejuvenated, Tristan heads back to Cornwall, where Marke’s advisors wish for the king to marry in order to eventually cut the high-achieving Tristan out of the line of succession by producing a new heir. Tristan, who doesn’t seem at all tired of running all over the place, is sent back to Ireland to secure young Isolde’s hand for Marke. Upon return, he takes on a false identity and casually slays a dragon, succeeding in his quest though not without some steamy tension as young Isolde of course finds out that Tristan killed Morold and threatens to kill him in return as he bathes— Scandalous! !

Regardless of Isolde’s feelings at this point in time towards Tristan, she is still set to marry Marke and bring peace between their respective kingdoms, so the journey back to Cornwall must take place. If you were a fan of the dragon before, prepare for another fantastical plot contrivance now, my dear, in the form of a love potion. Depending on the version you read the ensuing love potion mix-up is either deliberate or accidental, but regardless of circumstance, Tristan and Isolde end up drinking the potion on the boat over and they instantaneously fall madly in love with one another. Whether the potion lasts a mere three years or a lifetime, of course, also varies. It’s a choose-your-own-adventure kind of tale. However, it’s important that the blame for their love rests not on Tristan’s, because Tristan is characterised as a selfless figure of common decency, and most of all as someone who would never betraythe kindness and hospitality Marke has shown him. So he must then be powerless in it, love has to happen to him.

Regardless of that, being quite defenceless against the powers of the potion, Tristan and Isolde begin an affair that continues steadily on as she marries Marke. In some versions Isolde also has love for Marke, born mostly out of duty, while her true passion lies with Tristan. However you frame it, nightly trysts are not enough to sustain their need for one another, and the pair grows bolder and bolder until they’re eventually compromised by Marke himself.

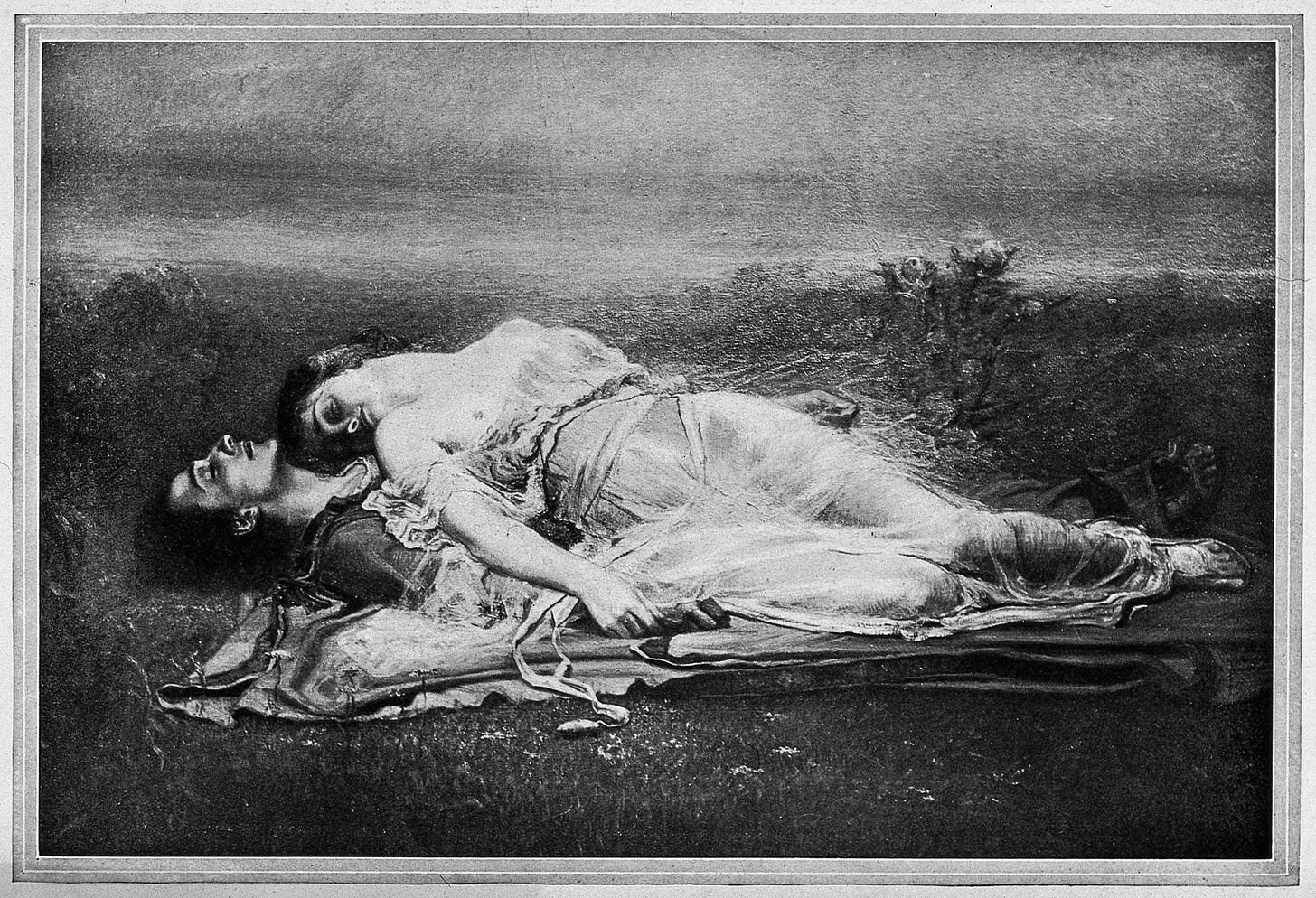

Tristan flees, marries a third Isolde [of the White Hands], and at one point is fatally wounded in combat. In his dying moments, he voices his great desire to see Isolde [the Fair], believing that she can heal him of yet another Irish poison. It is promised to him that the ship coming to his aid will have a white sail if Isolde [the Fair] is on board, and a black sail if she is not, but Isolde [of the White Hands] switches the sails so that when the right Isolde arrives, Tristan has already passed away from the heartbreak of believing he would never see his undying love again. Isolde gives him one final kiss before also dying from grief, right by his side.

Hearing this elaborate description, you might be intrigued to find out that there is a 2006 movie with none other than James Franco playing Tristan (yes, really). Not to mention a very young Henry Cavill, whom I did not recognise until at least an hour in. Anyway, they choose to twist the myth here, omitting the love potion altogether and instead having a full-on case of mistaken death for Tristan, in which his funeral pyre boat miraculously makes it to Ireland nearly unscathed, and the young Isolde finds him and nurses him back to health (gratuitous romance tropes commence, of course). The other two Isolde’s are omitted entirely as well, which is a shame, as the original’s hilariously confusing pantheon of female characters is endlessly amusing— even Tristan is confused by it at one point!

And just to tie things up neatly, Tristan also shows up in the “Inferno” in the circle of sexual sinners! Good company for Paolo and Francesca, I imagine.

II.IV Orpheus and Euridyce: Mythical and Doomed

“Eurydice, dying now a second time, uttered no complaint against her husband. What was there to complain of, but that she had been loved?”

by Ovid, from “the Metamorphoses” (ca. 8 CE)

In Ovid’s “Metamorphoses” (ca. 8 CE), Orpheus is a man known for playing the most enchanting melodies on his lyre, which was given to him by the god of music, Apollo. A weaver of the most beautiful songs, no one was immune to the charm of Orpheus’ music. And as he lived and played, he fell in love with the graceful Eurydice, and the two were speedily engaged to be married. But there were dark clouds gathering over their union before it could even properly unfold. Called to bless their wedding day, the goddess Hymen prophesied that the union was not meant to last. And so the story goes.

Unfortunately (or fortunately?), the fatal flaw in the two’s marriage was not through any of their own doings. Rather, it was nature that intervened, and one gentle day, Eurydice was either (1) pursued and harassed relentlessly by the shepherd Aristaeus, causing her to flee until she stepped on a snake, biting her. Or (2) Eurydice was dancing with the nymphs when she got bitten. Either way, the bite is fatal, and fair Eurydice expires on the spot, leaving poor Orpheus to his colossal tragedy, which all the world learns of through his mournful song.

But Orpheus is nothing if not determined, for he is used to his lyre’s ability to persuade, that sway his music holds over the likes of both mortals and gods, and he sets out to journey to the underworld itself to persuade its ruler Hades to allow Eurydice to return to the world of the living with him. When he finally gets to present his case, he plays a song so fragile and heartbreaking that it actually manages to chip Hades’ veneer and engender Orpheus’ cause to him. He allows Orpheus to leave with Eurydice, but under one circumstance: he must walk in front of her, and not look back until they have returned all the way.

A simple enough task, one might think, but the path was dark, and the shadows played constant tricks on Orpheus’ mind as he advanced. Doubt began to set in. He couldn’t hear Eurydice’s footsteps behind him, and so he began to wonder if she was really there at all, or if he had been tricked. The entire ordeal had seemed so easy… Could it be that he was the one being played like his lyre? With every step of the way, his resolve wavered, and just before the exit, it finally and decisively ran out. Orpheus turned to look, desperate to confirm or deny his suspicions, and as he did so, saw Eurydice standing right behind him, for just a split second, until she disappeared again to be trapped in the underworld forever. Lost to him.

As mortals cannot enter the underworld twice while alive, Orpheus spent his days in deep grief, lamenting his foolishness, wishing for and courting his own death to be reunited with Eurydice until it was finally delivered to him, and he embraced Eurydice again in death, knowing they never had to break apart ever again. A happy ending, I suppose, though the lovers’ sweet embrace would never feel alive or warm again in the cold depths of the underworld.

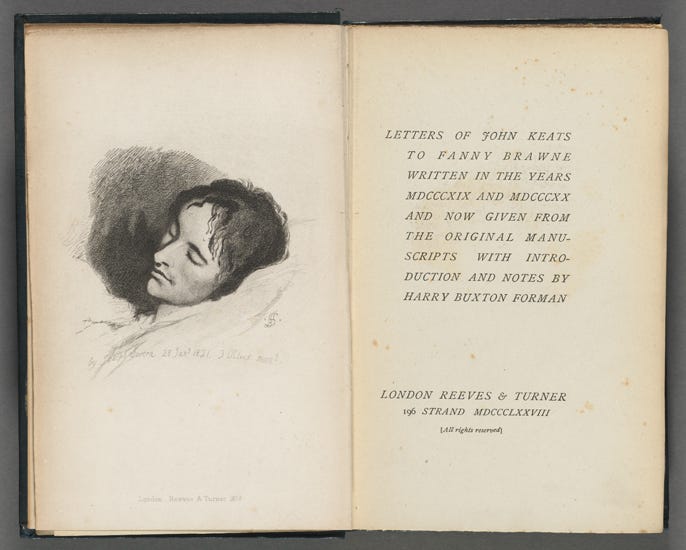

I.V John Keats and Fanny Brawne: Poetic and Doomed

“I have been astonished that Men could die Martyrs for religion – I have shudder’d at it. I shudder no more – I could be martyr’d for my Religion – Love is my religion – I could die for that. I could die for you. My creed is love and you are its only tenet.”

by John Keats, from a letter to Fanny Brawne (ca. 1819). Copied from “So Bright and Delicate: Love Letters and Poems of John Keats to Fanny Brawne”, introduction by Jane Campion, ca. 2009

When the poet John Keats first coughed up blood in 1820, he knew with singling precision that his life was to be cut drastically short. It was a dire night, the kind of cold chill that only February could carry with it, and Keats has just returned home in an open carriage, braving the wind and the cold, so that when he stepped through the threshold the first thing on his mind was the safety and warmth of his bed. This is when he coughs up the blood, and as his friend Charles Brown brings a candle to examine it, Keats discovers that he is looking at the starting symptom of an illness (consumption) that has already taken his mother and his brother Tom into an early grave: “I know the colour of that blood; it is arterial blood; —I cannot be deceived in that colour; that drop of blood is my death-warrant—I must die”. But it was not just the loss of his life that Keats feared. Not just the incessant worries of fading out of existence without a proper legacy to leave. It was also the death of his great love that caused him such anguish.

If we rewind the tape to just a year or two prior, we land right in the middle of it. John Keats, then twenty-four years old, met the young Fanny Brawne in autumn of 1818, when he moved into the opposite side of a house in Hampstead Heath, split in the middle to form two homes under one roof. On one side, there was Keats and his friend Brown, and on the other side lived the Brawne family. Young Fanny was eighteen years old and already a spirited, passionate person, described by a peer as “everything that one means with the word ‘unusual’”. It would be a huge understatement, however, to say that their meeting was not love at first sight. On their acquintance, Keats wrote in a letter:

“[…] but she's ignorant - monstrous in her behaviour, flying out in all directions… I was forced lately to make use of the term ‘minx’ – this is I think not from any innate vice, but from a penchant she has for acting stylishly – I am however tired of such style and shall decline any more of it.”

by John Keats, from a Letter to George and Georgiana Keats (1818–1819)

Not a very flattering impression, but the couple shared a group of acquaintances and friends, not to mention living right next to each other. Proximity was inevitable, no matter how accursed, and Keats and Fanny found themselves lingering closer and closer until their affections swelled. Marriage was out of the question, especially due to Keats’ financial prospects as a poet, and so the fiery couple’s love could grow unchecked, without the weight of a future upon them— something which would grow to be a burden rather than a benefit soon. From the summer of 1819 on, as Keats traveled throughout England, he started his now-famous correspondence to Fanny. The letters were extremely romantic above all else, but they were also frequent, vulnerable, funny, as well as jealous or possessive.

Upon his return, Keats attempted to move away from Hampstead in an attempt to break it off with Fanny, having no hope of being able to sustain her in marriage. The split did not work as intended: “On awakening from my three days dream… I should like to cast the die for Love or death”, and Keats promptly moved back to Hampstead. When they were together, and they were inseparable, Fanny would wear the ring he had gotten her on her engagement finger, and when she was with other people, on her middle finger. In their minds, they might as well have been promised to each other for eternity.

And that is where we are when Keats first coughs up arterial blood. With his illness quickly advancing, and him being unable to live near Fanny due to complications in Brown’s finances, it came to be that Keats pitted all hope for healing on a trip overseas. Meanwhile, Fanny had properly convinced her mother to allow her and Keats to marry upon his return from such a trip, if ever he did return, that is. As such, with future delight to live for, Keats traveled to Italy with Brown in 1820, desperate for the warmer climate to cure the ails of consumption, now far advanced— but ultimately, he succumbed to the illness, being only twenty five years old. While in Italy, he did not write to Fanny, finding the thought hopelessly unbearable. Upon hearing the news of his death, Fanny was beyond devastated, cutting her hair short, and choosing to wear full mourning assemble for the next three years, as a widow should. Completely undone by grief, she banished the thought of love for a long time, but ultimately married again at age thirty-five. She never took Keats’ ring off, though, until the very day she died, hopefully to be reunited with him in death.

And on that note, the curtain falls again. The lovers are resurrected so as to take a final bow.

Earlier, I mentioned a poem Keats wrote upon the “Inferno”, the last card in this spread of ours. You see, Keats gave his inscribed copy of Dante to Fanny, in which was contained a short verse of his, inspired by a dream he had after reading the passage of Canto V about Paolo and Francesca. He writes the following in a letter about his experience of Canto V:

“The fifth canto of Dante pleases me more and more- it is that one in which he meets with Paulo and Franchesca- I had passed many days in rather a low state of mind and in the midst of them I dreamt of being in that region of Hell. The dream was one of the most delightful enjoyments I ever had in my life- I floated about the whirling atmosphere as it is described with a beautiful figure to whose lips mine were joined it seem'd for an age- and in midst of all this cold and darkness I was warm- […] I tried a Sonnet upon it- there are fourteen lines but nothing of what I felt in it- o that I could dream it every night-”

by John Keats, from a letter to George Keats (1819)

III. Journal Prompts

“Poetry as a cemetery. A cemetery of faces, hands, gestures. A cemetery of clouds, colors of the sky, a graveyard of winds, branches, jasmine (the jasmine from Swidnik), the statue of a saint from Marseilles, a single poplar over the Black Sea, a graveyard of moments and hours, burnt offerings of words. Eternal rest be yours in words, eternal rest, eternal light of recollection.”

by Anna Kamienska, from “Industrious Amazement: A Notebook” (2011)

Now, for a little change of pace I would like to reel you back out from the romantic daydream you are no doubt enveloped in, back to a world of the self. My apologies, my dear. Seeing the date as it is I cannot in good consciousness write anything without acknowledging the precipice we are on within time. The end of a year.

Like many other full-time glamour aficionados, I too revel in having an extensive morning routine involving incense, tarot, stretches, tea, and, of course, some journaling time. It’s taken me a while to get over the performative nature of it that I impressed on it to begin with, but I find that it can be quite meditative if treated with care and patience. With the end of the year looming large ahead, now is as prime of a time as possible to reflect a little bit on the almost three hundred and sixty-five days passed, and for that purpose I’ve gone ahead and created some journaling prompts for you, my dear.

Treat them with caution and respect. Maybe have a nice cup of tea with them. Pick and choose which ones you like— there’s nothing wrong with having favourites! Make them yours, adapt them, fuse them together. Whatever works for you. The world is a haunted house, and you’re the spectre. You are driving the plot.

Journaling prompts for the end of the year:

Had you existed a couple of centuries ago, would you have been burned at the stake? If not, how can you work on that?

Did you make Angela Carter / Lord Byron / Mary Shelley / Oscar Wilde / [insert author here] proud this year?

Where do you draw the line between innocence and sin?

Are you the wolf, or the lamb? Which characteristics (of yourself or otherwise) do you assign or attribute to which one? How can you be more like one or the other?

What is it within the darkness that you fear?

Do you resist what you desire? Are you afraid of what you desire? Is friction in itself desirable to you?

How will you love yourself even if/when you’re monstrous?

Envision your ideal self. What are the smallest possible steps you can take towards that vision? (Think: things accomplished in one day, or built up day by day as a habit)

What was the most sensual thing you’ve experienced in the past year? Was it touch, taste, or some other sensation? What made you inhabit yourself without shame?

“I will always be the virgin-prostitute, the perverse angel, the two-faced sinister and saintly woman.”

by Anaïs Nin, from “Henry & June” (1986)

And with that, we close the book on our mirage of doomed romance, our chain of dying daisies, our thread dyed red with lovers’ blood. The year is fast coming to an end and just a week ago I had a mouse lodging in my house, sneaking about as if he owned the place. I caught the unusually polite little thing and set it free within a local park, right by a beautiful stack of gravestones.

Personally, I spend my fragile evening making chainmail now, hypnotised by the weave as I open and close the rings to attach them. Open and close, open and close, open and close. Boredom is just a lack of imagination. With every cut that suddenly appears on my hands I grow further and further away from it. I wrap the ceaseless red in my arteries around myself like a red riding hood waiting for her wolf, a costume fit for an adventure into myself, tied into a bow. If I sinned it was only because I was hypnotised by evil; the beauty of it. Permanent hide and seek within the same gilded cage.

For those gathering soon and for those going on pilgrimage, I wish you light and love. May you find (or make!) a place for tenderness to bloom. Remember to keep your head screwed on straight, and don’t untie that lovely ribbon around your neck. You know what will happen if you do. No matter what, you are always a saint to me, my dear. The new year will bring with it many more letters, rest assured. Life is not lived in the all or nothing. It is always both, and neither. See you on the other side.

Until my next letter,

With love (and violence),

x Sabrina Angelina, the White Lily Society

Currently reading: “The Call of Cthulhu and Other Weird Tales” by H.P. Lovecraft // Most recent read: “A Spy in the House of Love” by Anaïs Nin

White Lily Society links // Sabrina Angelina links

Why lament the tragic end to Romance? Here at the White Lily Society we learn to swaddle ourselves in beauty and pain, romance and tragedy, love and violence. It’s the best comfort around, so why not join? Why not subscribe? Come on, become a martyr of deliciousness.

My winter (and general) Byronic hedonism lifestyle guide is available in Newsletter 05, just in case you’re not a winter fanatic like me.

In the original “Decameron”, ca. 1349, she is called “Lisabetta”

All the Isolde’s can also go by Iseult, depending on version. Either spelling goes. Tristan is also sometimes known as Tristam.