16. Apotropaic

In attempt to ward off evil.

“November, slaughter month, the month of blood.”

by Rebecca Perry, from “Beauty/Beauty” (collected in “The Year I Was Born: the day by day chronicle of events in the year of your birth”, 1990)

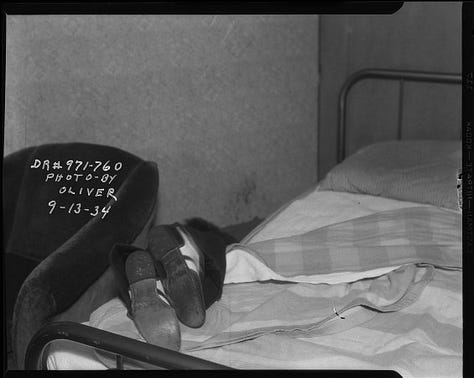

TW: Because this newsletter focuses on forensic sciences and crime scene photography, real images of crime scenes will be featured. These do NOT contain any gore or visible blood (most images filtered B&W), and for the most part do not contain parts of corpses that could not reasonably be written off as just mannequins (ie. no faces, no visible signs of decay, no full body shots). Images from films might still contain fake blood. Viewer discretion is advised.

01/11/2024, London, UK

My dear,

First of all, I hope you had a lovely Samhain last night, filled with haunts and coziness and spirit[s]. It is, after all, the time when the veil between the world of spirits and the world of the living is at its thinnest. A time when the world seems like a thread of silk, fragile and vacuous. And if you were to ask me, this veil of cobwebs remains thin all throughout the barren winter months. November is a cat on your doorstep, begging feverishly for a dish of milk. Can you hear it? And accompanying it is a time for wondrous tales and firesides and days so cold you can see your own breath. Evidence of your supposed existence in between the veils.

I do not endeavour to sugarcoat things needlessly. This October/November newsletter quickly spiralled out beyond my control, as they tend to do— you know this fact of life much better than me. Before my eyes the writing flashed and morphed and changed, out of my control. The end result is a true thing of multitudes. This here newsletter is a eulogy, is a deep-dive, is a celebration. Come, let me take you to the scene of the crime. The thick of it, if you will. The eye of the storm. Your very own needle in a haystack. A swan-song that ensures its own survival. After all, we don’t often write our songs down unless we are in danger of forgetting them. We only ride on the tongue of the giant beast when it is necessary to our memory’s survival.

Under my own lace veil I have been taking silence like communion. I have consulted the spirits and the ancient tomes alike. I think dissection of a thing, any thing, counts as a valid metaphor for love. In my dreams there are mice in my home or perhaps I am just three centimetres taller. Little things like that, little incisions, little wounds. Everything is poetry to me, everything can be. Taking something apart is often how you learn to put it back together. So, let’s take up the scalpel, shall we?

Oh my, what an odd array of things inside of this one! Quick, quick, come see! Yes… I see it now. No new write-ups on socials, but oh there are glorious submissions awaiting you! Two of them, to be very precise— a good mortician always is. Two of them, weighed out here. Our very own “dead girls” themed submissions. One poem that blends the harshness of beauty with the supposed tenderness of constructed girlhood, and one concerning societal violence against women. Both equally mesmerising and enchanting little wriggling things. Be quick to catch them before they slither off of the operating table.

Now, if you would please take off your gloves for a second, we have a great many of things to get to today.

I. Archive Updates

“The more you investigate the crime, the more you feel into it, the less you are capable of judging it, because you find when you go deep enough, that the crime was exceedingly meaningful, that it was inevitable in that moment—everything led up to it.”

by Carl Jung, from a seminar somewhere 1934-1939

It should come as virtually no surprise to you that, like with a lot of my letters, this one was heavily inspired by a talk I attended in the past month. The truth is, my dear, that I was fully and intentionally planning on writing about medieval literature for this issue, and then life had other plans and I, in my infinite weakness, let one faithful evening lecture completely derail those carefully laid plans. This was a lecture by Catriona Byers (@/heymorguegirl) for London Month of the Dead called “Shot Dead: Crime Scene Photography in Art & Culture”. An endlessly intriguing talk, and one with a personal connection to my lore, as you will see. You could even say crime scene photography runs in my blood. And it will run through yours too, temporarily, after you’ve absorbed all I’ve served you today, my dear.

You have been warned, deliciously and grotesquely.

“The Uncanny” - link

A fundamental text for any student of horror, Sigmund Freud’s paper on the “uncanny” is ground zero. Ubiquitous and ripe with ideas (some more well-founded than others), this is a paper that features Freud’s signature style and concepts (fear of castration, etc.) but combines it with snippets of genuinely interesting and thought-provoking rhetoric. Though I’m not always a fan of the long-windedness of his writing, I do think there is a merit at starting at the “scene of the crime”— the root, if you will. This is a foundational text, and a must-read to then build on top of.

“The ‘uncanny’ is that class of the terrifying which leads back to something long known to us, once very familiar.”

& “[…] for this uncanny is in reality nothing new or foreign, but something familiar and old— established in the mind that has been estranged by the process of repression”

“Murder in Black and White: Victorian Crime Scenes and the Ripper Photographs” - link

The concept of distance is a major concern of this short paper talking about some of Britain’s earliest crime scene photography, that of Jack the Ripper’s victims ca. 1888. In it, author M. Anwer talks not only about a distance between camera and crime scene, but from viewer to victim, and the effects this had on the Ripper victims’ legacy. All but one of these gruesome pictures discussed (not shown!) feature no full body shots, no images of the victim in contact with the scene, but are rather shot like portraits of disfigured faces staring into the lens. Fuel for the imagination. Though this is a short read, it is packed with information and references to expand on.

“Confronted with this fluidity and expansibility of the scene, the crime-scene photograph struggles to fixate, stabilize, and localize the crime through chemicals on a piece of paper. Thus to photograph crime is not just to document it, but also to hope to contain its threatened overflow, to limit its proliferative potential and neutralize its danger. The forensic photograph is meant at least in part to disconnect and exclude the contents of the photographic frame from the world that lies beyond its borders—the very world that must be protected from being turned into a crime scene.”

“Weegee's Voyeurism and the Mastery of Urban Disorder” - link

Somehow, someway, all my readings and analyses always lead me back to “scopophilia” and “scopophobia”: the pleasure and the fear of looking or being looked at. We will talk more about Weegee, a father figure to American sensationalism in crime scene photography, later, but for now there is this text offering a nice overview of his work, attitudes, and legacy. Despite being most [in]famous for it, Weegee didn’t just photograph crime. His work focuses on all kinds of disorder ranging from fires to murders to simple scenes of (mostly innocent) chaos, mass culture, and celebrity. Through the text, we learn he had a preference for the bizarre. That his invasive cynicism juxtaposed the ubiquitous anxiety of crime with the ubiquitous anxiety of surveillance channeled through his camera. The fear of being looked at, being watched. “Weegee first makes us accomplices in the unadulterated pleasure of looking”.

“[Weegee] managed to create a persona that, by the mid forties, had come to stand for the very thing he depicted in his work—the disorder of the modern city, in all its violence and passion. And, simulta-neously, Weegee had also come to represent an attitude toward urban disorder, a strategy for coping with the anxiety of the cultural moment.”

II. Forensics Frenzy

“Everything is a self-portrait. A diary. Your whole drug history’s in a strand of your hair. Your fingernails. The forensic details. The lining of your stomach is a document. The calluses on your hand tell all your secrets. Your teeth give you away. Your accent. The wrinkles around your mouth and eyes. Everything you do shows your hand.”

by Chuck Palahniuk, from “Diary” (2003)

II.I Something old, something borrowed

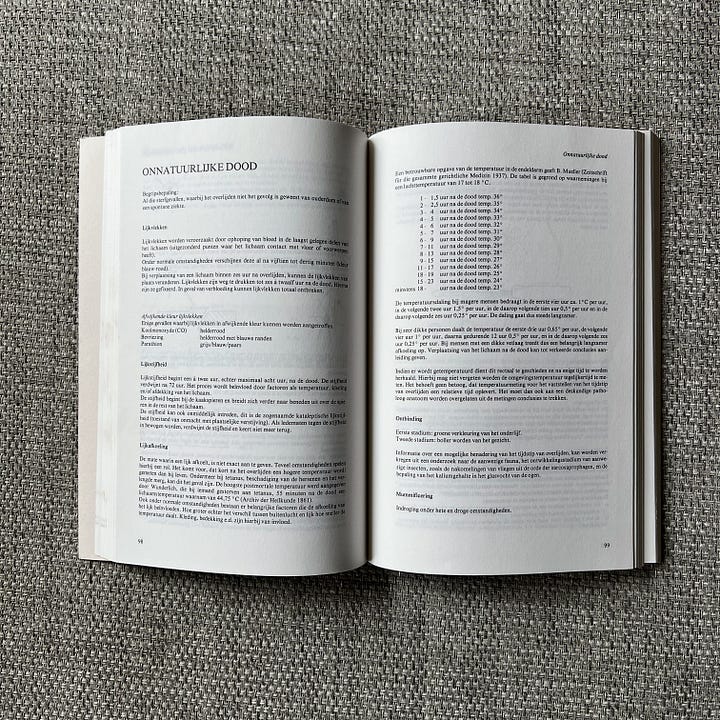

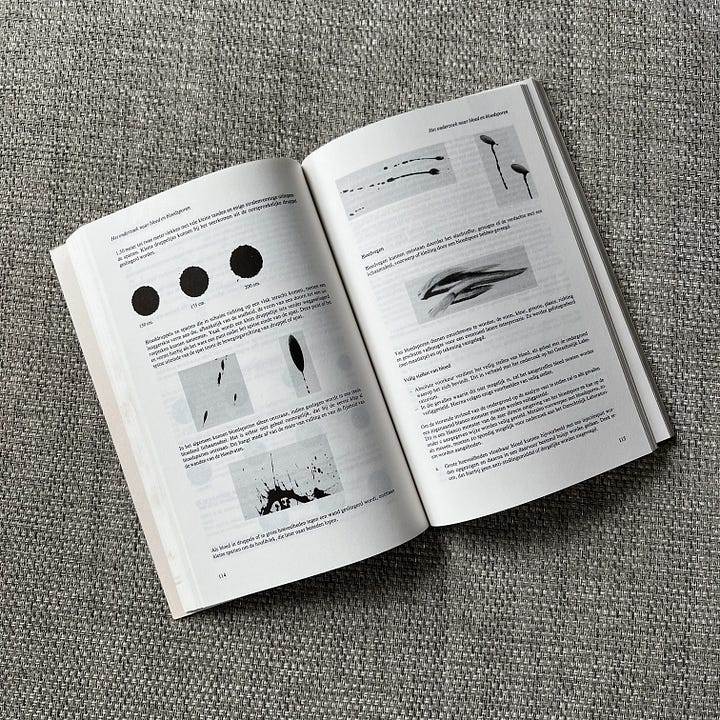

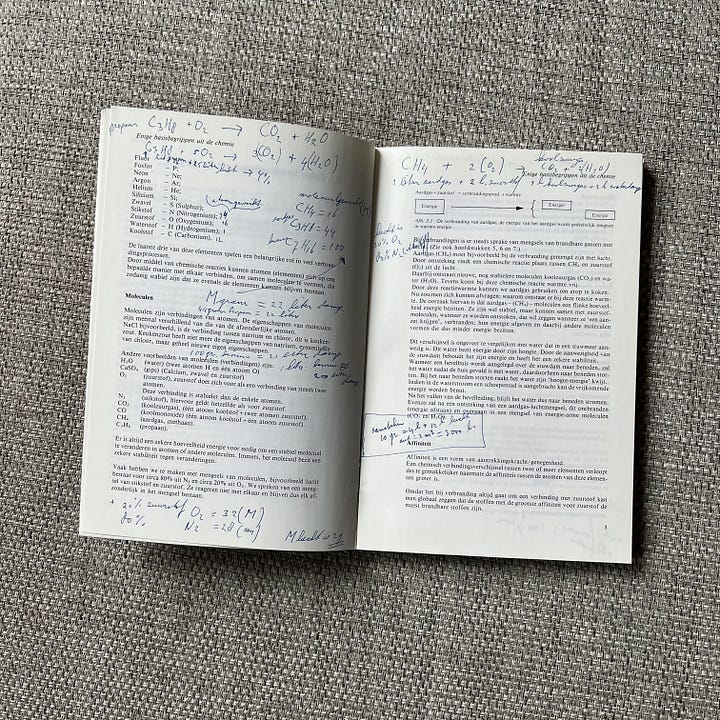

The other main instigator for my foray into the dark and criminal today was of course my late grandfather, whom I eulogised briefly at the end of newsletter 14. But for those not in the know I’ll tell you now that my grandpa- besides being an eccentric- worked as a detective and crime scene photographer back in his day (not to mention a stint in the air force as a meteorologist). A few years ago, he took to handing down all his old odds and ends to me, under the guise of feeding my interest in antiques and helping me properly source the crime novel I was writing at the time. I’m talking fingerprint brushes, Dutch forensic institute magnifying glasses, and several insignia, but also a heap of old cameras, related gear, and most importantly all his old handbooks from his time as a detective, meticulously annotated and all.

Unfortunately for you I am not under the delusion that you are fluent in Dutch (and if you are, hey twin!), but I do wish to include some images of these books here with some descriptions, as I find them very stimulating to peruse from time to time, or even just to leaf through and look at the various illustrations. When I was little and I stayed with my grandparents in their attic, I often dug up one of the books on the shelf there at night, a chronicle of crime entitled (in Dutch): “Murder and Homicide in West-Overijssel, 1946-2006”1. Probably not the best reading for fertile minds, but I digress. Come closer, dear, take a look at my trinkets.

II.II A little history

“Photography is an elegiac art, a twilight art. Most subjects photographed are, just by virtue of being photographed, touched with pathos. An ugly or grotesque subject may be moving because it has been dignified by the intention of the photographer. A beautiful subject can be the object of rueful feelings, because it has aged or decayed or no longer exists. All photographs are Momento Mori”

by Susan Sontag, sourced from “The Social Photo: on Photography and Social Media” (p.26, 2019) by Nathan Jurgenson

As always, there is no deep-dive without a proper foundation to build it on. We must pay our respects to our elders, to our history, before we can embroider on. A tapestry without a proper start is just a collection of threads. Which, in turn, is easily frayed.

What we see is what we usually take as the truth, that much I know. “I saw it with my own eyes!” is perhaps the most basic condition of absolute truth. Eyes don’t lie. Except, of course, when they do. Our very willingness to take sight as absolute truth is a fallacy in itself that carries on over into the world of photography, which, like our sight, is also infinitely coloured. Not just by what it sees, or what it thinks it sees, but by what it doesn’t see. And it is not just the photograph that is coloured, tinted, influenced. This primal inconsistency is nested in the eye itself, right in the lens of the camera. “Much about what we choose to shoot, how we understand it, share it, present it, and see it is conditioned by the specific design decisions of the currently popular devices and services […]” (from “The Social Photo: on Photography and Social Media”, Nathan Jurgenson, 2019, p10). The tools often create the vision, create the work. This is important for what is to come.

The art of photography came about in the late 1840s— something which I’ve been reading about lately because one of the many cameras my late grandfather left me originates from (possibly) the 1920s. It’s a beast of a thing, solid in stature, that works with a “wet plate collodion” or “ambrotype” process (successor to the more well-known “daguerrotype” process): taking pictures on glass using liquid collodion and silver albumen. What I’ve found most fascinating about this type of photography is that the whole process from prepping the plate, to taking your photograph, to developing it needs to be done in roughly twenty (!) minutes. Ever wonder why all those Victorian photographers like Julia Margaret Cameron mostly shot in homes or their garden? This is why. The wet plate process requires a dark room to be on-hand at all times. Again, the tools dictate, shape, and create the work. Not the other way around.

Let’s return to the matter at hand. While crime photography was around in the late 1840s and 50s in Belgium and Denmark, the idea of a unified theory of crime photography started with a Frenchman named Alphonse Bertillon in the 1880s. Bertillon laid the groundwork for a more-refined procedure of photography which attempted at a more objective methodology following a process of rigid, predetermined steps. Most importantly though, he set up the idea that crime photography was mostly useless if it did not follow the same conventions, angles, lighting, etc.— An idea which would metamorphosize into the standardised mugshot, or portrait images of criminals for the sole purpose of identification. Before that, from the 1850s, there were galleries of criminals for the public to view (“rogues galleries”), but the images used were not standardised in the way Bertillon would go on to suggest, and thus were far from reliable measures of identification.

Additionally, images of crime scenes took a while to morph into the mannerisms we associate with it today. As seen in Archive Source 2, Victorian crime scene photography was not yet focused on crime scenes but on bodies and faces of victims, plucked out of context. For this they often used extremely high overhead camera angles achieved with massive, looming tripods to get a “god’s eye view” shot entirely parallel to the victim’s body laid out on the floor. The early 19th century saw the art of photography as an “apparatus for insight” (Archive Source 2), which extended to making photography an art of examination, of voyeurism, of complete obliterative moral judgement: “The human face was believed to confess the corruptions of the soul—if not always to the naked human eye, then to the camera, which was thought to possess a magical power to elicit our darkest secrets.” (Archive Source 2)

But at the same time as crime and crime scene photography came of age, so did the forensic sciences alongside it. Fingerprinting, toxicology reports, DNA analysis, ballistics and firearm analysis, and other standardised forms of investigation all blossomed on their own time and eventually combined to create a well-rounded scientific method by the precipice of the 21st century. The task, then, became to teach this method to the ever-rotating selection of detectives and investigators at any given precinct.

One such way of teaching and standardisation came courtesy of Francess Glessner Lee in Maryland in the late 1940s through her “Nutshell studies of Unexplained Death”, also known just as the “nutshells”. These miniature dollhouse scenes, of which there are twenty in total, took Glessner Lee twenty years to complete and are incredibly detailed and vivid in their scenery. Meant to train new forensic investigators on how to collect evidence from a crime scene, these meticulous 1:2 dioramas are complete with working lights, realistic blood splatter patterns and bullet trajectories, and based on real crimes. Students training with the nutshells got about 90 minutes to collect as much evidence from viewing them as possible before presenting their theories and getting the “solution”.

Most interestingly, the nutshells’ array of precisely planted evidence is often contradictory and enigmatic, prompting careful consideration when formulating theories. The answers to the nutshells are still kept under lock and key, even when the dioramas themselves have sometimes traveled the United States as art objects on their own, mostly out of context. Regaled for the scale and intricacy of the crafts displayed within.

Glessner Lee’s is often hailed as the “mother of forensic science”, not to mention her legacy as the first female police captain in the US, but her motivation in making the nutshells was mainly to standardise a method of forensic studies that was more precise and left less room for the clumsy mistakes the era was known for. Oftentimes, crime scenes were tampered with due to negligence, and key evidence could often go missing or be neglected entirely. But the nutshells played a large part in training forensic investigators to have a keener eye, and it was all done using often easily disregarded “feminine” domestic arts and crafts, through an odd marriage of craft and crime. Glessner Lee was “both exacting and highly creative in her pursuit of detail- knitting tiny stockings by hand with straight pins, hand-rolling tiny tobacco filled cigarettes and burning the ends, writing tiny letters with a single-hair paintbrush, and creating working locks for windows and doors.” (“Murder Is Her Hobby: Frances Glessner Lee and The Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death”, the Smithsonian American Art Museum, 2017). A highly resourceful and imaginative solution to a criminal problem, don’t you think?

II.III The “Look” of Crime

“The same camera that photographs a murder scene can photograph a beautiful society affair at a big hotel.”

by Weegee, date unknown

I bet that if I asked you to close your eyes right now, and imagine a crime scene, the results would be just what I expect them to be. A domestic scene, at night, probably in black & white, ambient lighting and furniture almost picturesquely in disarray. The picture perfect crime.

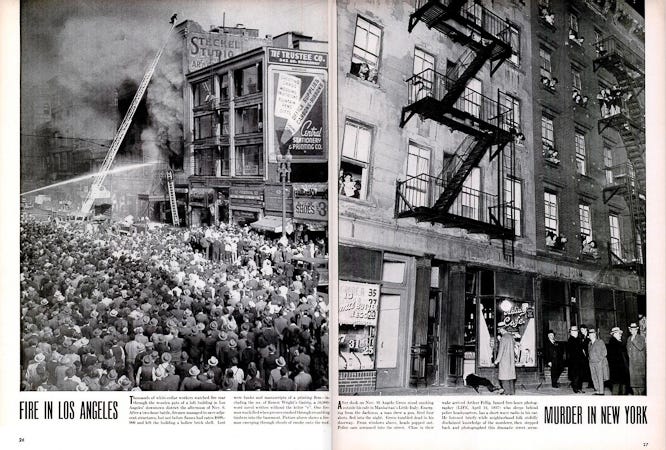

Undoubtedly there is some sort of a cultural fascination with crime scenes, and with it a construct of what we expect a crime scene to be, how we expect it look. This “crime scene aesthetic” as we can so readily call to mind was largely influenced by American photographer Weegee, the pseudonym of Arthur Fellig. You might have met him briefly in Archive Source 3, but I will recap nonetheless. Weegee (dubbed “Weegee the famous” by himself, a self-fulfilling prophecy) was active as a press photographer for newspapers and tabloids in the 1930s and 1940s, and is credited with largely popularising and establishing the cultural framework of crime scene photography. Utilising a hard flash in his black and white images, and having an eye for the most tender shots of human disorder, Weegee sold his pictures to tabloids and newspapers at truly prolific rates.

The popularity of Weegee’s work undoubtedly thrived on the fact that he often got to the scene of the crime first, sometimes even before responders or law enforcement— in 1939 he was the only non-police associated photographer with permission to install a police radio in his car. He always got the prime cut of whatever tragedy unfolded itself in front of him. And he had an eye for compositions that called out to people: images of children sleeping on fire escapes, a mother in distress watching a building burn with her young children trapped inside, images of devastating fires releasing enormous smoke clouds as onlookers watch in awe at the destruction in front of them. He was not above photographing a murder victim and selling the image. And he fully acknowledged this fact.

As Weegee became more well-known, he started taking more images of celebrities as well as crime photos, and he published and sold them side by side, most famously in his book about New York entitled “Naked City” (1953).

“He made blood and guts familiar and fabulous”

from the New York Times, on Weegee’s work, 2012

One must wonder why people are so eager to buy, sell, and trade in other people’s misfortunes. I write “are” and not “were”, because only recently the NYPD still had crime scene images for sale for personal use, ranging in subject matter from murder to suicide, to hit-and-runs. A practice they only stopped recently after eight years of business. A little bit of immorality to clean out the archives. A necessary evil, some might say.

But in comparison to the NYPD’s crooked yard sale, Weegee’s images did not come completely devoid of context: “Weegee established a way of combining photographs and texts that was distinctly different from that promoted by other picture magazines” (from the exhibition “Weegee: Murder is my Business”). These captions were often cynical or humorous in nature, and they often displayed a sort of photographer’s entitlement to images. A hubris. An entitlement to voyeurism, if you will. When subjects covered their face at the sight of his camera, he expressed annoyance: “They should have thought of that before they went into the crime business” (Archive Source 3).

The idea of pairing visual and text alone loosely reminds me in its own way of the pre-Raphaelite brotherhood’s tendency for “twinned” works of art in the middle to late 1800s: they often paired painting with poems to take advantage of both mediums’ strongpoints and to fill in the other’s gaps. Where visuals didn’t suffice, the written word would and vice versa. Maybe there was a reason Weegee thought his work shouldn't be condemned to stand on its own, beyond artistic vision.

Because Weegee’s work is complex and nuanced, far more than I could put into words without you seeing it. Or at least a lot more of it. Not only does it sensationalise crime for the masses, but it also serves as a sort of judgement on the disorder of the criminal, a distant relative of Victorian morality pictures. It was a way of packaging and relating to crime in a way wholly new to the US2, and therefore largely influential on the cultural zeitgeist as it spread.

Another thing most influential on our humble understanding of what crime looks like is of course film noir. You absolutely know it and can picture it, even if you don’t know the films that started the references. Detectives sat in the harsh shadow cuts of window slats with fedoras, chain-smoking cigarettes, and catching the crook in their own, well, crooked ways. Film noir as a phenomenon started in the 1940s, and as the French in its name might imply is all about the “black” or dark side of life. Its narratives focus on corruption, the dark underbelly of society, crime and punishment, eroticism and seduction, cynicism, betrayal, and paranoia. Their melodramatic heroes are often lone wolves going up against a broken system or [almost] seduced by a life of crime.

Almost as important to these films as their morally diverse plots was of course their highly stylised vision. Like in Weegee’s images, film noir used the black and white film it was shot on to create shots with rigid and precise compositions, odd angles, and deep contrast (“chiaroscuro”). Its visual language also heavily featured close-up shots of specific details or minutiae as if puzzle pieces to the larger mystery of the film. Urban environments, domestic scenes, and poverty and disrepair all feature heavily, and are all aspects we commonly associate with crime [scene] iconography— the expected language of crime, both real life and fiction. The archetype of crime.

Speaking (writing?) of archetypes, another thing both film noir and crime fiction have in common is that they love to typecast their [main character] women into one of two categories: evil woman // dead woman. These are the women that set the plot in motion. Of course, there are mothers and daughters and helpful maids, but they are rarely the instigator of the plot, they only help smoothly guide it along. So, evil woman // dead woman. On one side of the coin there is the femme fatale, using her sexual wiles and beauty as a lure. She is a killer, she is a manipulator, and she is, as far as the narrative is concerned, the lowest of the lowest when it concerns morals. On the other side, we have the victim. The poor, unfortunate, dead woman— or more often a girl. Incidentally an archetype we looked at in depth in last month's letter.

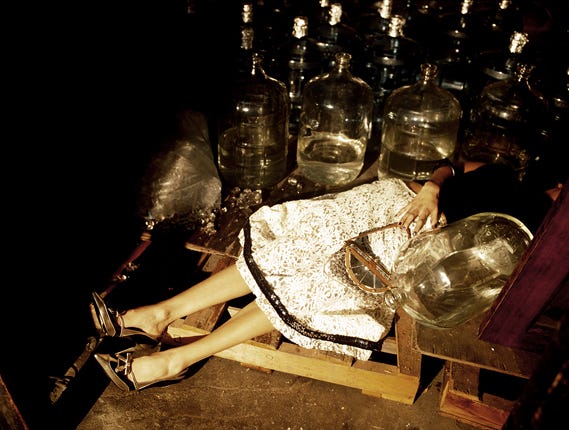

When fashion photography channels crime scene inspired imagery, as it has before, it often references these female archetypes to suggest woman-as-killer or woman-as-victim, both equally sexualised and fetishised in their doll-like portrayal. If they are the first, they get a little more power over the image, they get to actually inhabit more of the shot. If they are the latter, they are often boiled down to a selection of features, a pair of disembodied limbs (most often legs) dangling dramatically with the rest just out of view. Anonymity forced upon them.

One such series of fashion photos inspired by crime scenes is Melanie Pullen’s “High Fashion Crime Scene” series, which feature many shots of almost comically neat “crime scenes” of women laying or hanging about, seemingly dead but completely devoid of blood and gore, and always impeccably dressed. The vast majority of them just feature the women’s legs, wearing stockings and high heels. Glamorous until the very end.

Pullen writes on her portfolio website that the idea for the images “came to [her] from being exposed to several images of violent crime scenes in [her] teenage years. These images horrified and haunted [her] for a long time, as [she] was suddenly faced with my own immortality.” David Lynch, another artist largely influenced by the language and mystique of crime, writes in his memoir that he “he [in his youth] encountered a beautiful naked woman walking down the street, bruised and traumatised. ‘It was so incredible. It seemed to [him] that her skin was the colour of milk, and she had a bloodied mouth.’ He was too young or too transfixed to find out who she was before she vanished.” (from the Guardian’s review of “Return to Dream: a Life in Art”, David Lynch, 2018)

If you’re here, I probably do not need to tell you of the human capacity for the morbid. You, my dear, are the proof of it. Even if we do not mean to be, we are fascinated and captivated by images of violence or implied violence. They leave a stain on the soul. This intrigue largely comes from an [often traumatic] illicit desire and interest, as we have seen for the two aforementioned artists, Pullen and Lynch. Where mortality and violence meet our eyeballs we are often haunted after. Regardless of whether we see the image as beautiful or not, there’s a lingering feeling that we really shouldn’t be looking at this, that it’s taboo, that we should avert our eyes with a fervour that leaves whiplash. “It’s like looking at a car crash: it’s horrible, but we can’t look away” and variants. This effect is what Georges Bataille would refer to as “eroticism”. Interaction with the taboo is what connects us to a transcendent greater whole: it brings the continuous to us, discontinuous beings. It’s a touch of the universal and that is exactly why it hooks us so.

“For each man who regards it with awe, the corpse is the image of his own destiny. It bears witness to a violence which destroys not one man alone but all men in the end. The taboo which lays hold on the others at the sight of a corpse is the distance they put between themselves and violence, by which they cut themselves off from violence. The picture of violence which we must attribute to primitive man in particular must necessarily be understood as opposed to the rhythm of work regulated by rational factors.”

by Georges Bataille, from “Erotism: Sensuality and Death” aka “Eroticism” (1957)

II.IV True Crime, True Anxieties

“The oldest and strongest emotion of mankind is fear, and the oldest and strongest kind of fear is fear of the unknown”

by H.P. Lovecraft, from “Supernatural Horror in Literature” (1927)

But looking at a corpse or any other form of death is not just a stark reminder of our own mortality, it is also, in certain ways, a victory over death (see Georges Bataille, “Erotism: Sensuality and Death” aka “Eroticism”, 1957). Freud theorised in his 1920 work “Beyond the Pleasure Principle” that we all possess a “death drive” or “Thanatos”, a subconscious instinct meant to shepherd us back to our inevitable death. But that “death drive” is not just an explanation for self-destructive behaviour, but also for the almost sadistic and morbid nature that constantly circles us back to the concept of death. For those looking at crime scene photos or other aspects of death and violence, there is an aspect of inflicting terror upon themselves, micro-dosing the plethora of anxieties wound up in what they’re consuming. Not just fear of death, but for crime scene photography also a fear of the other, a fear of misfortune.

It’s known that the population at large widely overestimates the likelihood of crime befalling them, and that fear of crime has been growing since the 1960s. In a way, crime scene photography is almost perfectly tailored to this fear. With every crime scene image, there is always a distinct sense that we have “missed all the action”, we arrive “in medias res”. The harm is already done. The perpetrator has already come and gone without us so much as even lifting a finger. It is a story, a film, a play where we are utterly and devastatingly resigned to the role of the viewer, despite the emotional rawness of the shot making us feel very much like a main character.

Like crime scene photography, true crime also plays an egregiously large part in growing anxieties about crime. At the heart of both is a violation of [mainly] domestic spaces, a disregard for the safety of the home as well as the safety of public third spaces. The house becomes an elaborate fortress with no way to keep out the intruders, the broken streetlight on the way to the grocery store a perfect place for a crime of passion, the public park a scene of an intense and random assault. True crime has no regard for place, person, or time of day. If we were to take its doctrine to heart, then anybody can be a victim of anything at any point in time. Nowhere is ever truly safe.

Everything always comes back to bodies. Bodies, bodies, bodies. The harm that comes to them, the ways in which they are displaced, the ways in which we all inhabit them. But even if you were to ignore that a small majority (56%) of violent crime perpetrators in the UK’ recent violent crime statistics were known to the victim (22% domestic violence + 34% acquaintances), those same statistics have shown that violent crime victimisation rates have remained below 2% since 2014. In 2022 there were “only” 12 homicides per million people. There was, and still is, relatively little reason to think you are exceedingly likely to meet with violent crime like true crime would suggest. The anxiety that comes as a cost for your fascination is still largely unwarranted. Insert a sigh of relief here.

II.V Getting Weird With It

“I have looked upon all the universe has to hold of horror, and even the skies of spring and flowers of summer must ever afterward be poison to me. Who knows the end? What has risen may sink, and what has sunk may rise. Loathsomeness waits and dreams in the deep, and decay spreads over the tottering cities of men.”

by H.P. Lovecraft, from “the Call of Cthulhu” (1928)

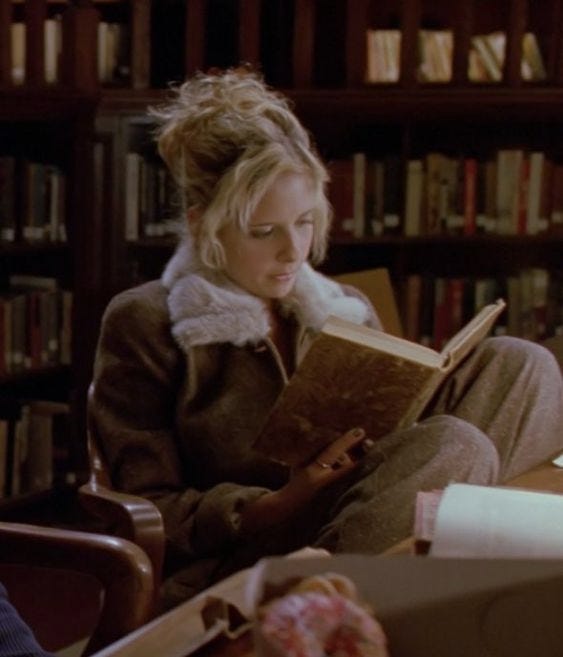

Now, personally, I’ve always been fascinated by supernatural detective stories rather than your average Watson and Holmes. Safe for only the most twisting cases, I am simply not in the business of dealing with reality. Ever. Rather give me fantasy, sell me an illusion, paint me a pretty picture and I’ll be a hell of a lot more satisfied. Because where the vanilla detective story is all about the outcome first and the process second, the supernatural detective story tends to put much more stock in the path of getting to its outrageous conclusions. And it does so beautifully, too. Thinking about “monster of the week” shows like “Buffy the Vampire Slayer” (1997-2003) or even certain seasons of “the Vampire Diaries” (2009-2017), their investigative process is always distinctly cozy3. Nested in the Sunnydale High library (or the Salvatores’ outrageously fancy wood-panelled home), their scenes of sleuthing revolve around a step-by-step process of research that is both full of warmth, and uniquely rewarding.

Supernatural crime fiction or metaphysical detective stories, whichever you may, usually depends on you, the viewer to take a leap of faith when it comes to its deductive process. Take for example the famous "Tibet" scene from S01E02 of “Twin Peaks” (1990-1991), David Lynch’ famous mystery show revolving around a murder, paranormal influences beyond our knowledge, and a police agent with less than conventional techniques. After info-dumping about the country of Tibet to his partners-in-crime-solving, agent Dale Cooper, goes on to tell them [that] “following a dream [he] had three years ago, [he has] become deeply moved by the plight of the Tibetan people, and [has] been filled with a desire to help them. [He] also awoke from the same dream realizing that [he] had subconsciously gained knowledge of a deductive technique, involving mind-body coordination operating hand-in-hand with the deepest level of intuition.”. He then throws rocks at a glass bottle several feet away as one of his accomplices lists the names of [potential] subjects, placing further priority on those names that are accompanied by a hit. Odd indeed.

Dreams, too, feature greatly in Cooper’s investigative reasoning, as we have seen. A dream is just as valid as a hunch or a proper clue, and is treated with the same reverence and respect. Most importantly, Cooper’s methods aren’t outright rejected by the people closest to him. They may raise an eyebrow or lack understanding, but they are mostly willing to go along with the madness, just to see where it leads them. No harm, no foul. Perhaps this is because intuition generally is already a big and well-established part of the [fictional] detective arsenal. The classic “My gut is never wrong” trope, something which Marvel also recently poked fun of in S01E01 of “Agatha All Along” (2024), in which main character Agatha Harkness is under a delusion that she is the protagonist in a gritty, realistic, probably Scandinavian-flavoured crime story. Yes, complete with the whole “gut” thing.

Where Twin Peaks fascinates me, though, or rather where the entirety of the supernatural blending with crime fiction does, is that it naturally brings out the mystical elements of the traditional crime thriller. Genres like metaphysical detective stories and occult detective fiction blend two ideas that on a surface level should mix like oil and water (that is, to say, not at all): objective logic on one hand, and the unexplainable or supernatural on the other. This is mysticism. Crime fiction is almost religious on a fundamental level. There are rituals to be obeyed: bureaucracy, the traditional order of investigation. There is the aforementioned “higher” power of instinct, but there is also another god to bend to: the law. Invisible, far-reaching, revered. There is a strict hierarchy: both of class, of importance, and within the justice system. And there is a violent act, a reconstructed crucifixion, at the centre of the tale.

“There are photographic fanatics, just as there are religious fanatics. They buy a so-called candid camera. There is no such thing: it’s the photographer who has to be candid, not the camera.”

by Weegee, date unknown

Hell, there are many origin stories for the aforementioned “Weegee”, but one of them directly alludes that the name is a reference to the Ouija board (pronounced the same way), mostly because he loosely claimed psychic nature in getting to his photo opportunities early. Mysticism aplenty!

You might even be inclined to take things one step further, really dial down on the weirdness and blend cosmic horror with detective fiction. But just because these supernaturally flavoured stories and detective fiction have a similar underlying mysticism doesn’t mean they always merge well because their other ideas are fundamentally at odds: detective fiction à la Sherlock Holmes is all about knowing, while cosmic horror à la Lovecraft thrives on the notion that you can never know, because the act of knowing will drive you to insanity in the face of things you could never understand, so knowing is fundamentally not knowing. There is no way out of the maze. Don’t go looking for answers you don’t want.

My favourite video game, “Bloodborne” (2015), plays with this as well. The game blends a great amount of references, but its most obvious one is Lovecraft, whose work famously “[…] foregrounds the limits of human consciousness and the incapacity of our senses and language to accurately capture unnameable nightmares that defy representation” (from the introduction to “the Gothic tales of H.P. Lovecraft”, edited by Xavier Aldana Reyes, 2018). In its own impenetrable, hidden narrative, Bloodborne’s horror revolves around contact with its lore’s “Great Ones”, gods beyond our mortal understanding. Beings of infinitely sumptuous motivations. Just to see them drives one mad with frenzy. One of the main groups in the story’s lore, the Choir, maintains a philosophy that one must have eyes (insight) to communicate with the Great Ones, or even to tolerate the Eldritch Truth. They do this in their experiments by attempting to line the brains with eyes: “Our eyes are yet to open” / “Grant us eyes” (from “Bloodborne”, 2015).

And so we return to eyes, to our own perception of things. Tying everything up into a neat little bow. You thought I was needlessly derailing this talk, didn’t you, my dear? That’s okay, but I would love a little more faith in me going forwards. The moral of the story is that we see as much as our eyes allow us to. A camera is an eye, or an extension of our eyes. Our vision is not an infallible god. Sometimes it is not just about what we see, but about what we don’t. What exactly is hiding just out of view.

III. On turning two

Happy two years of madness, my dear! It’s been a little over two years now since this beautiful, fragile dream started on the 26th of October 2022, and oh, what a few years it’s been. What a lovely cult this is, that we’ve so carefully co-created for the past two years. This last year in particular, has been so incredibly soul-wrenching and fulfilling— it’s brought tears to my eyes on more than on occasion, I confess. So many new society members gained this year! So many more connections! Forgive me for being a bit high on my own feigned importance.

There is, of course, a laundry list of achievements I could list off here to celebrate the cause: 1000 society members on Instagram, a 100 subscribers on Substack, our very first submissions, our very first meet-up events, and so much more. If you’re ever curious (and I know you possess a boundless curiosity), then feel free to gawk at the infancy of the society and our full story so far, here. I’ve spelled out the entire timeline and do intend to keep adding to it as time goes on. All my secrets laid bare.

I always fear the stylistic choices in this newsletter’s tone reduce anything heartfelt I am writing (typing) to mere glamorous pulp, but believe me when I say that I am pressing it full of sincerity. My time is absolutely never wasted building this amazing community of little freaks (lovingly), and this year I wish to do more things to encourage that community feeling! I absolutely adore it when society members leave comments, when they write to me, when I get to meet them. That’s the kind of warmth, the kind of flame we all must feed. Thank you for being here, my dear. You’re the entire reason I get to do any of this <3.

“But days, too, of the wild blackness of great autumn storms, followed by dank, wet, streaming nights when there was witch-laughter in the pines and fitful moans among the mainland trees.”

by L.M Montgomery, date unknown

And so, the haunting melody of another month’s mad musings must come to an end. October is but a dying dream. The tragedy is only as far as you keep it. At arm’s length is a condition, not a state of being. If you wish it so, you could press everything closer to your chest, let it completely consume and devastate you. But the bitter and the sweet will always take the stage in alternating turns. That is a promise, my dear. At a Keats House event this past month, an actress playing Fanny Keats mused that “[you] too will meet with your share of pleasure in the world”. I chose not to doubt it, and neither should you.

If you open your eyes all the way, there is always a tragically beautiful something stuck in your lashes. I saw a woman kick a butterfly, completely on accident, and completely and blissfully unaware. The poor thing brushed it off, unscathed. In all the connecting tissue of a life a simple accident probably means very little to it, to us. Such is the way of all flesh. The magnifying glass you hold up to your own life is probably unwarranted.

“Do you still perform autopsies on conversations you’ve had long ago?”

by Donte Collins, from “Thirteen Ways of Looking at Thirteen” (collected in “Autopsy”, 2017)

So, finally, my last incision, my last fading note, my last trick will be a recipe for good winter months. Pay full attention. Ingredients: two scoops of brown sugar, a lock of hair from the beloved, hair dye and a magnitude of rings and chipped nail polish. A cloak. A persecution fantasy, rotted idealism. Postcards to send to faraway friends. Two foxes and a magpie, preferably seen playing in a cemetery during a grey afternoon. Rooibos tea. Artifice. Embroidery, straight onto skin: a scar to keep (one old, one borrowed, and one new). Daydreams of elaborate romances. Park benches. A library of folk music. Apotropaic custom. A hunter who loves you in pursuit of their treasures, a gentle beast. Holy rage. Lady/knight customs. Candle anxiety, an unstoppable desire to lick the flames. A friendly comparison to the bride of Frankenstein. Community.

Until my next letter,

With love (and violence),

x Sabrina Angelina, the White Lily Society

Currently reading: “Arthurian Romances” by Chrétien de Troyes // Most recent read: “Graveyard Shift” by M.L. Rio

White Lily Society links // Sabrina Angelina links

Breaking: unknown stranger reads entirety of this lengthy newsletter without being subscribed! Why not return to the scene of the crime a few more times, why not subscribe? I’m not saying I’ll set the cops on you if you don’t, but I’m not not saying that. Come on, become a martyr of deliciousness.

For those who care: “Moord en Doodslag in West-Overijssel. 1946-2006, zestig na-oorlogse jaren in kaart” by Willem Visscher

Of course, there are other countries who have their own version of Weegee, revolutionising local crime scene imagery, but I’ve chosen to focus on the states here. If you’re interested in more, you could perhaps look into Enrique Metinides in Mexico City— someone who I’m not very familiar with beyond his name.

Great article on this here: “Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Research as a Public Good”, from academicalism.wordpress.com