24. In Hospital

By authority of the Commissioners in Lunacy.

“July nights are short; soon after midnight, dawn comes.”

by Charlotte Brontë, from “Jane Eyre” (1847)

TW. This meat and bones of this newsletter (Section II) is an extensive foray into the history of madness, London’s asylums in the 17th-19th century, and asylum horror. There will be respectful paragraphs touching on real-life institutional trauma, including brief descriptions of inhumane treatment. For my fellow emetophobes: there is a mention of the word “emetics” in sections II.II and II.III, no description or elaboration. There is a word-only mention of SA in section II.III in the quote towards the end. It is not further elaborated on. Reader discretion is advised, as always.

01/07/2025, London, UK

My dear,

Summer madness has properly taken root in me. Tangling like briars in my stomach, and my head, and my thoughts are wiped clean. Sweat is the ultimate purifier. My dreams have grown more frequent, and I visit three of my friends’ dreams in one night. Busy, busy, busy. Besotted and beset by the hounds, I awake in my room, afraid of encroaching insanity. God, even masochism fails in the vicinity of a sunburn. And in the sweltering heat the city buses are more like beasts, like gentle giants, monsters of the road that huff and puff and sigh. We are all heating up, eternally, and never cooling down.

My dear friend Anna de Waal said it best when she wrote that “Everyone knows how the moon makes lunatics of us but remember that in June, madness becomes the sun’s domain”. The sun is associated with warmth, but also with fire, with intensity. Here is a list of things my friends have associated with me in the last month; the word “ambrosial”, goth Paris Hilton in “Repo! The Genetic Opera” (2006), worn lace, well-loved pearls, scuffed stylish boots. Fine foods on crystal platters, graveyards, the delicate bones of a bird. Cinderblocks. The sound of bells ringing. Using these you can invoke me whenever you wish. I trust you’ll use the ability carefully, my dear.

This month we are taking the scalpel to madness. I have rustled through the London Archives and through many books, visited apothecary attics and operating theatres, have gotten my leg sawed off by a dear friend to get firsthand experience. What I have laid out for you today is an attempt to re-invent the history of the London asylum, to diagnose the madness of fear, the fear of madness, to alleviate the aches of the mind.

So, fill in this brief intake form for me, will you? I am just eager to get us started…

This newsletter contains the following sections:

I. Archive Sources // II. Asylum-Bound (topic dissection: asylum history, horror & hydrotherapy) // III. a New Look (about the new WLS logo) // “On the List: July” // Outro (w/ end of summer affirmations) ✧・゚: *✧・゚:*

I. Archive Sources

“But here was a woman taken without her own consent from the free world to an asylum and there given no chance to prove her sanity. Confined most probably for life behind asylum bars, without even being told in her language the why and wherefore. Compare this with a criminal, who is given every chance to prove his innocence. Who would not rather be a murderer and take the chance for life than be declared insane, without hope of escape?”

by Nellie Bly, from “Ten Days in a Mad-House” (1887)

Step into my office, please, my dear, and do close the door behind you. Before we open the archives, we must pad out our case-file a bit, so to say. Get the clippings and the second opinions and the multitude of pamphlets out. The notes scribbled in the margins and the pictures attached with pristine paper-clips. A post-mortem requires some cutting and reassembly, after all. Consider these sources your first incisions. A taste of the madness to come.

“H.P. Lovecraft and the Madhouse” from “The Literature of Madness: A Critical Study of the Madhouse in Gothic Literature” - link

Another writer oft-associated with madness, and by extension with the asylum, is H.P. Lovecraft. But it is interesting to note that his American perspective frames the madhouse as a sort of retreat. Yes, an unusual amount of Lovecraft characters have their brushes with insanity, but as the author of this paper brings to light, their madness is not of a psychological or internal cause, but rather caused by witnessing greatly stressing external truth. While the hospital is still frightening, and so is the prospect of madness, it is also, paradoxically, considered by Lovecraft to be a state of higher knowledge. The voices of the mad have a place there, an odd comfort amidst the cosmic horrors of Lovecraft’s writing.

“For Poe, madness calls into question the reliability of his narrators; for Lovecraft, madness is always an empathetically reasonable response to the threat of impossible, incomprehensible and unknown things from elsewhere; here, madness gestures towards the post-human body and the fearful processes of becoming or of encountering the other. For Lovecraft, this effect is emphasised by the fact that his writings deal in mad knowledge, and as a result, madness becomes a source of authority in his fiction.”

& “Lovecraft gothicises the madhouse in a departure from the Victorian oppressor of truth, and in a way that is not as exploitative of mental illness as in later Gothic asylums; for Lovecraft, the madhouse is sanctuary and madness is a legitimate claim to authority.”

“The Feminization of Madness in Visual Representation” - link

Carefully examining an array of engravings from the 18th and 19th century, this paper takes a look at the specifically feminine gendered expectations of madness, such as in archetypes of the “Ophelia” love-struck melancholic woman. Clearly, this ideal of a madwoman in opposition to the madman is a character also threatening male power, but doing so through sexual suggestiveness and aggression of social norms (as opposed to physical aggression). Only later on did the characteristic of physical aggression get grafted onto the stereotypical madwoman, as melancholy came to be less associated with insanity than with the human condition itself. This transition was completed during the early nineteenth century, as the depiction of the madman morphed into a more sensible gentleman, while the madwoman got the manic, irrational, aggressive treatment— a perfect visual to aid in curbing women’s up and coming wish for equality and cement them as irrational, dangerous, and overly sensitive.

“By the 1850s, when asylum statistics first confirmed the perception that female inmates were likely to outnumber their male counterparts, figures of mad-women, from Victorian lovestruck, melancholic maidens to the theatrically agitated inmates of the Salpêtrière, already dominated the cultural field in representations of madness. This situation denotes a clear shift in the understanding of madness as a gendered disorder […]”

“Narrative and the Mental Health System: Removing Horror from Mental Health Experiences and Environments” - link

While the traditional horror-soaked narrative of the asylum has certainly done more harm than good, this paper argues that narrative as a tool can actually be used to recontextualise them. Looking at some real-life experiences of traditional mental health institutions and their similarities to folk horror through sheer setting and structure, this paper goes on to look at an example institution which reversed these negative traits and yielded positive results— a hope for mental health care that does not inadvertently destabilise its wards.

“As a health practitioner, I had become blind to the system that I worked in. So familiar had I become with stories of trauma within unusual settings, that I had not fully accepted that the links to horror were being reinforced by the modern systems and cultures in mental health care environments. […] Scovell outlines that folk horror stories are traditionally set in places isolated from mainstream society, places that have their own sets of rules outside of societal norm, places where strange and uncanny events happen to those within the system (often against their will) and where people held within the environment are cut off from trusted relationships.”

II. Asylum-Bound

"And lo, the Hospital, grey, quiet, old, Where Life and Death like friendly chafferers meet. [...] A tragic meanness seems so to environ These corridors and stairs of stone and iron, Cold, naked, clean - half-workhouse and half-jail."

by William Ernest Henley, from “Enter Patient” (collected in “In Hospital”, 1903)

As many of you know, I occasionally spend a day or two a month volunteering at Highgate Cemetery, a gorgeously overgrown Victorian cemetery: a resting place for live and dead alike. On my languid bus rides home, now sweltering in the heat, I always pass by the abandoned old Archway Hospital, standing tall in the face of centuries changing. The large brick building is imposingly Victorian, looking every bit the part of a haunted asylum, all boarded up and shrouded in secrecy. It speaks to the imagination, and oh, it spoke to me. It whispered all manner of phantasmagoria into my ear, begging for a bit of research.

As it turns out, the old hospital was in fact not an asylum, despite having the atmosphere of a proper madhouse to its brick shell. Looks can be deceiving, my dear. Nevertheless, the seed was planted… Asylums were on the mind… June madness and a simple spark make for a great instigator, it seems.

II.I a Little History of the Asylum

“Madness no longer exists except as seen. The proximity instituted by the asylum, an intimacy neither chains nor bars would ever violate again, does not allow reciprocity: only the nearness of observation that watches, that spies, that comes closer in order to see better, but moves ever farther away, since it accepts and acknowledges only the values of the Stranger. The science of mental disease, as it would develop in the asylum, would always be only of the order of observation and classification. It would not be a dialogue.”

by Michel Foucault, from “Madness and Civilisation” (1961)

The asylum as we imagine them started all the way back in the fifteenth century in the Netherlands, with madhouses (“dolhuizen” in Dutch) designed simply to keep the insane off the streets, to avoid disturbances to public peace. The notion of treating the mad, what we commonly associate with the asylum, was still a distant dream, and would be for another few centuries. No, the first concern was simply to get the mad off the streets, and separated from the other “nuisances” of society. Before that, there were separate establishments aimed at keeping the homeless and “idle” incarcerated and forced to work; correction houses that severely punished the supposed sins of the deviant. But the Dutch soon realised a need to keep the sick separate from the (in their eyes) slothful, and so they started the madhouse.

Seventeenth century France, by contrast, had very little interest to sequester the sick away from society at large. The care for anybody struggling with mental health issues fell largely on their family, whose best interest was in keeping their relatives confined in secrecy, lest shame befall them. The madness of the day was shame, and treatment was secrecy. Best to keep the unruly under lock and key within the home, or, if the family grew exceedingly tired of the burden their unlucky relative provided them with, they could petition the king to issue a lettre de cachet, and have them confined indefinitely in a religious institution— if this sounds familiar, my dear, it’s because this treatment was the same one provided to the notorious Marquis de Sade. Scandalous, indeed.

It goes without saying that abuse of this system was rife. Where there is a will, there is a way, after all. It wasn’t unusual for political opposition to the King to be locked away, or anybody else who had crossed the wrong (powerful) people, and the masses didn’t take long to start voicing their discontent with this system. But while in France the lettres de cachet and their inevitable abuse evoked a mass fear of false imprisonment, the English associated the madhouse with another form of mistreatment: one motivated by greed. English society was, at the time, rapidly inventing new services and products to advertise and sell, and new professions to go along with it. The care of corpses, for example, and everything a death in the family brought with it, was now being taken out of the domestic space and into the hands of specialised undertakers. Madness was no different, my dear.

A trade of lunacy was quickly established, and proven to be quite lucrative indeed. Like in France, the British largely saw their mad relatives as stains on their family reputation, and they were willing to pay to be rid of the burden they provided. But the madhouse was still more prison than treatment facility: “Neither licensed nor regulated to any significant degree throughout the century, and in the business of providing tactful silences, madhouses were often isolated and sinister spaces.” (by Andrew Scull, from “Madness in Civilisation”, 2016, p134).

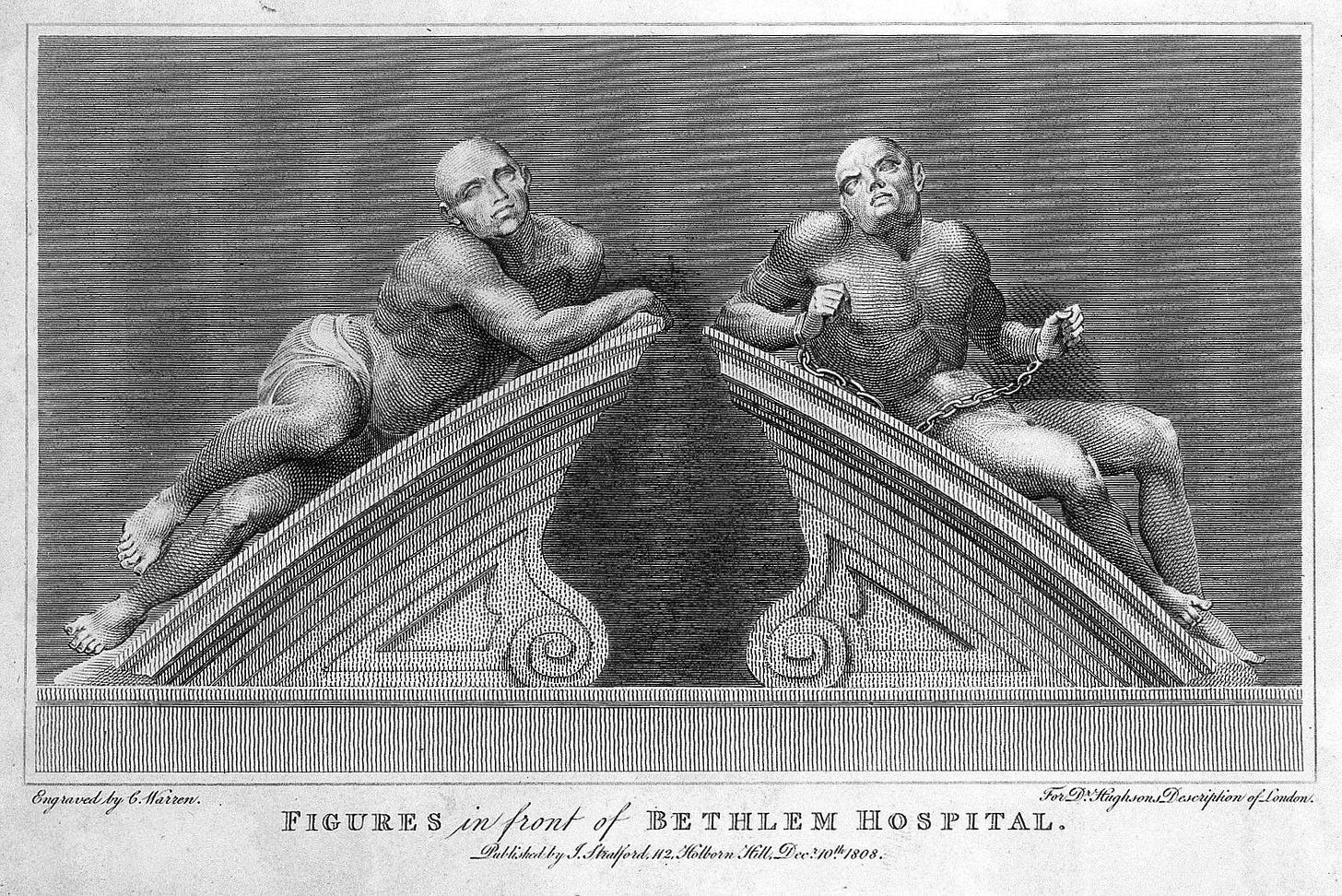

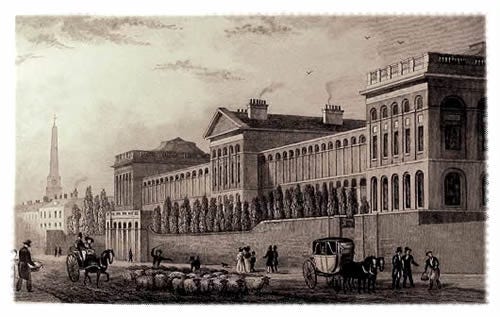

London’s very first and most famous madhouse was Bethlem Hospital (more often referred to as “Bedlam”), founded in 1247, though only dedicating itself to the insane somewhere in the fourteenth century. Admittedly, very little is known about the treatment of its patients during the medieval period, though it likely included restraint and seclusion. It seems paperwork took a long while to get into fashion as well. But Bedlam undeniably continued to grow with the centuries, and its position as the most prominent London asylum was largely unshaken, despite the hundreds of small charity hospitals that also popped up with the times. No, the first time the infamous Bedlam gained any sort of competition was with the founding of St. Luke’s Hospital for Lunatics in 1751.

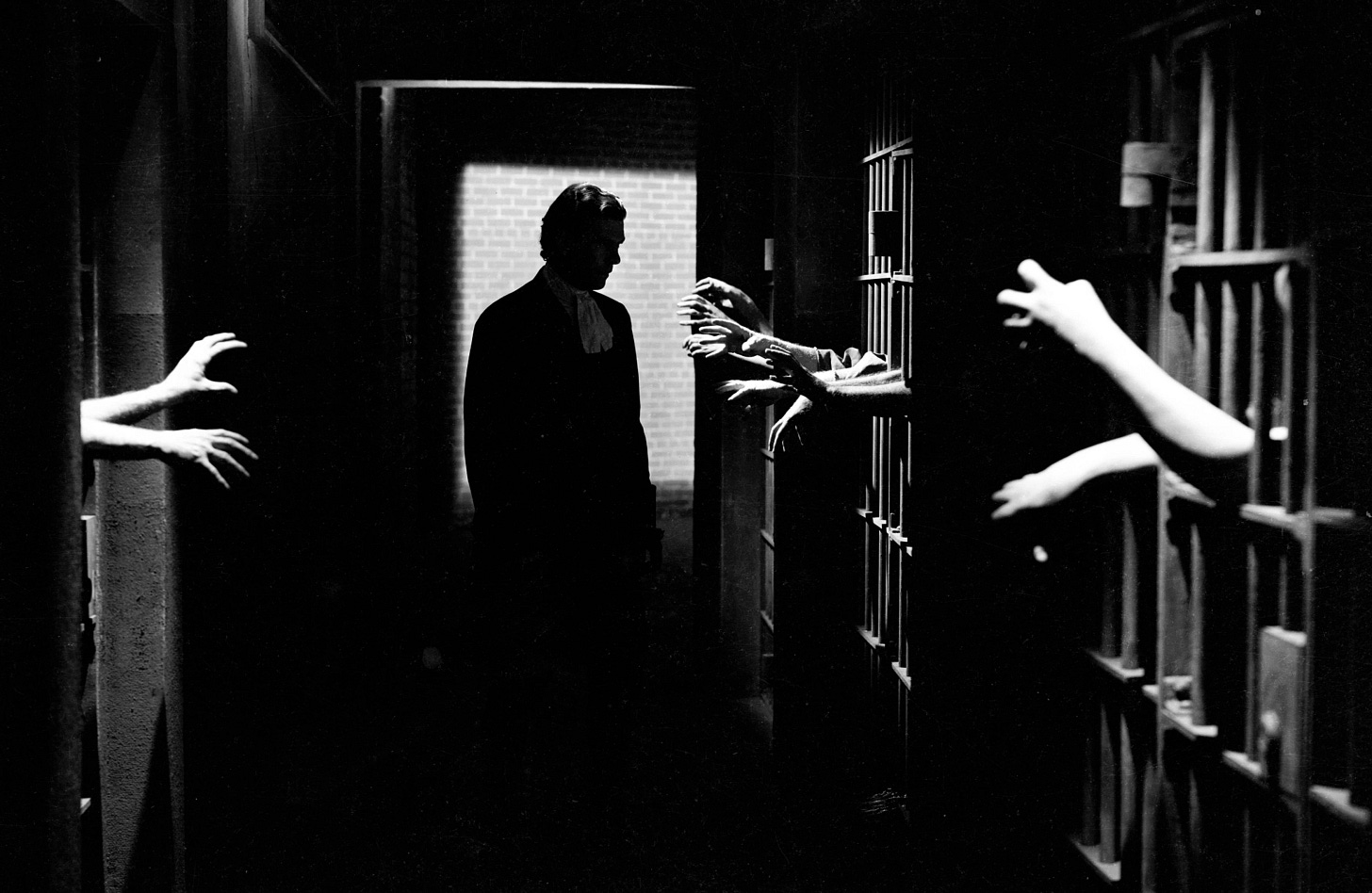

Whereas the newer parts of Bedlam has been quite extravagant, pandering to the pockets of its wealthy patients no doubt, St. Luke’s was grim and minimalist, fashioned with bars over the windows, plain-looking, and clumsily situated into existing buildings. The asylum business was about discretion, and they cared little if their patients were cold, hungry, or chained up. The idea of purpose-building a hospital, too, was quite unheard of! It’s no wonder then that the general population soon came to be frightened of the madman, exacerbated by their jail-like environments, and the Gothic imagination which loved to sensationalise the madhouse.

II.II Asylums of London and the History of Madness

“In important ways, that is, madness is indelibly part of civilisation, not located outside of it. It is a problem that insistently invades our consciousness and our daily lives. It is thus at once liminal and anything but.”

by Andrew Scull, from “Madness in Civilisation” (2016), p10

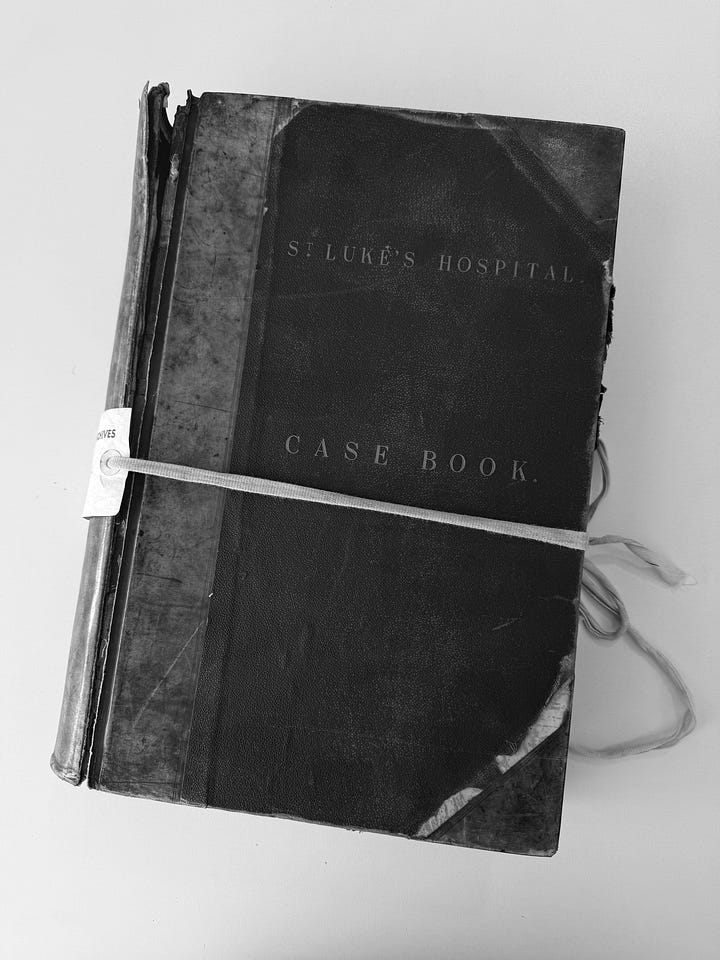

This time around, writing this letter, I was not content simply picking up bits from books and articles, and fashioning a monster of my own. Perhaps the sun had gotten to me, or perhaps I simply imagined myself a Very Serious Writer, out on the trails to find myself a story. Nevertheless, my first stop, emboldened in my capacities as a researcher, was the London Archives, where I spent a day leafing through the registers and paperwork of some of the major asylums, 1791-1935. My main focus was on St. Luke’s Hospital for Lunatics (Bedlam’s records being exasperatingly hard to track down), and the Asylum for Idiots (Surrey, 1847)— though the latter was not located in London, some of its files are available at the London Archives because its superintendent brought the files with him when he went on to found Normansfield Hospital, which was situated in London.

[I have included my request history in the footnotes1, so you can retrace my steps if you wish to, my dear..]

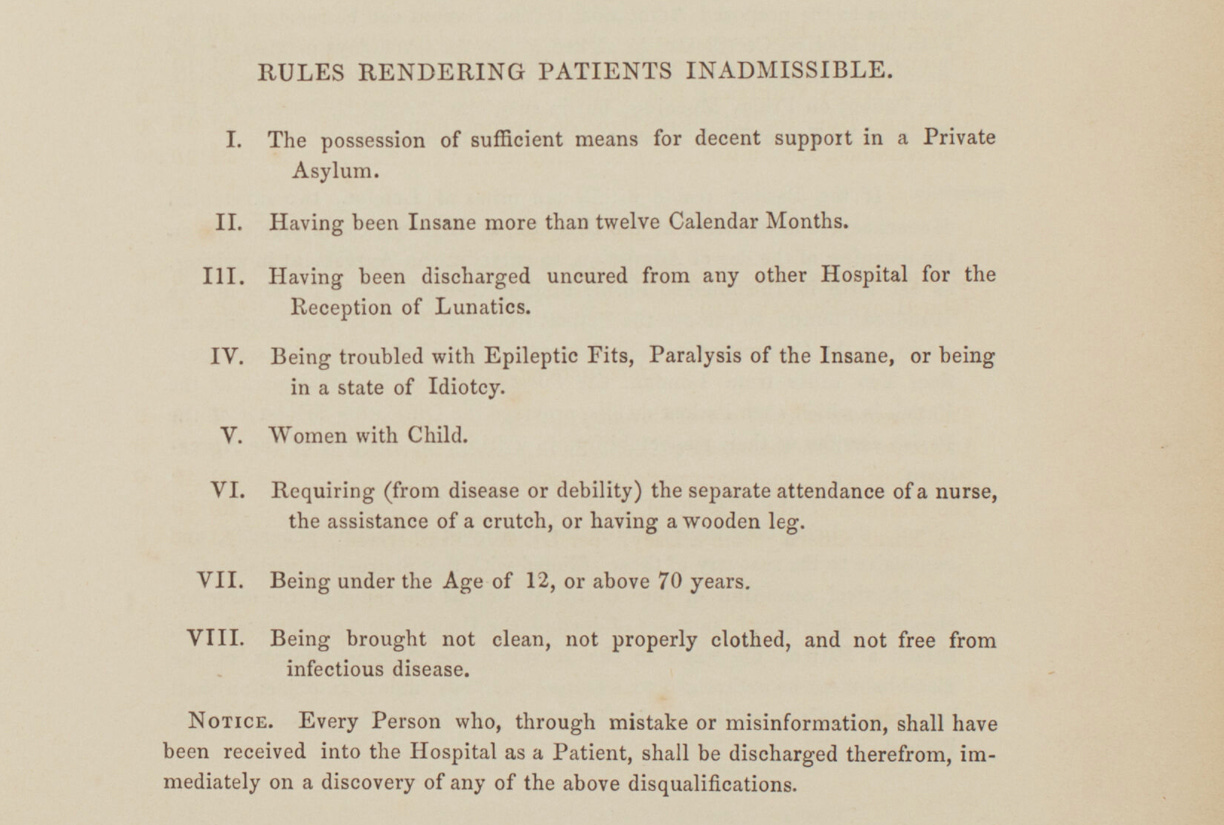

St. Luke’s hospital was in business from 1751 to 2011, and admitted a wide range of patients deemed “curable” or “incurable”, on account of mania, the monomanias (not distinguished in the records, but generally thought to be nymphomania, kleptomania, and the likes), melancholia, and acute dementia. From the records of its first century of operations (1751-1851), rules rendering patients inadmissible were quite tight; being pregnant, previously treated at any other hospital, or insane for more than twelve months all disqualified you from being treated at St. Luke’s. In 1850 (one of the years for which detailed records survive), the majority of patients admitted as “curable” was aged 26 to 25 years old, almost 2/3 stemmed from the countryside as opposed to the city, and most were servants by occupation or simply listed “wife” as their profession— women outnumbered the men by 107 to 72 that year. The same is true for the century 1751-1850, when St. Luke’s “curable” patient history recorded 10778 female patients to 7311 male patients.

One such male patient was “F.B.”, a 37yo cabinet maker, who went for a stay at St. Luke’s Hospital in April of 1851, his intake noting his “attack” of mania as being caused by “losses in business & drink”. Admitted by his wife on account of posing a danger to both himself and others, his physician wrote the following “evidence of insanity”: “That he is confused in his ideas; has failing of memory, uneasiness, restlessness, is terrified & regards everyone with suspicion as meditating something against him & has made use of threats of violence against himself, his wife & a constant restlessness, sleeplessness, fear & suspicion of everyone who approaches him, sudden startling as it from seeing phantoms. an evident feeling of some dreadful evil impending—”2.

F.B. was discharged as recovered in November of 18573, a full six years after his admittance to the hospital— much longer than the average stay, which was 2-4 months at the time of his admission, or 3-6 months at the time of discharge4. During the first century of its operations, St. Luke’s dealt with 18089 patients deemed “curable”, and cured 7818 of them (roughly 43% of the total “curable” patients), as well as a further 660 admitted as “incurable”. And while women outnumbered the men as patients, they matched those numbers in cures as well: of those admitted as “curable”, 5005 women were cured, as opposed to 2813 men. A total of 1821 patients died across categories, most commonly, it seems, from exhaustion5. Noting that the population of London was around 2.3 million in 1851, those are quite significant numbers for just one of the city’s many asylums to process, though perhaps less so when taking into account that patients clearly were prepared to travel from the countryside to be treated in the city’s asylums.

Notes of treatment supplied at these asylums is noticeably sparse throughout the archives, or is simply illegible to modern sensibilities— those cursive handwriting styles are a most challenging opponent, my dear. Sometimes, they are scrapbooked with legislations and treatises, like the 1913 regulations on the mechanical restriction and restraint of patients, issued by the Commissioners in Lunacy, stating that all restraint should be documented and constantly supervised. Out of the list of restraints allowed, two in particular speak gruesomely to the imagination:

the “continuous bath” - a form of long duration hydrotherapy in which the opening of the bath is covered to exclusively allow the patient’s head out.

the “wet or dry pack” - a wrapping or restraining of the full body in sheets, sometimes soaked with water.

Seventeenth and eighteenth century opinion fully insisted that an iron fist was the only way to rally the mad back to sanity: “Discipline should therefore accompany the traditional medical remedies of the depletion, evacuation and bleeding.” (Scull, p145)— even King George III was not exempt from this notion, and was met with corporal punishment as part of his so-called “treatment”. Foucalt writes that “Fear appears as an essential presence in the asylum.” (from “Madness and Civilisation”, 1961). For a while, fear was thought to be the cure to madness, and a brief period of time also favoured the idea of disorientation as healing; whether by sensory deprivation, shocks, or through elaborate swinging mechanisms that did not agree with patients’ stomachs. Records from 1851 also show that St. Luke’s experimented with the use of ether and chloroform, but found the substances lacking in regards to actually curing the mad. Generally, asylums favoured a treatment consisting of a heavy detox program of combined laxatives and emetics, as if madness could be one of the waste products its patients emitted.

Think of a modern juice cleanse taken to extremes, though you’ll be hard-pressed to find a modern spa offering authentic period experiences…

II.III Oh, my Nerves!

“Madness is the product of society and of moral and intellectual influences.”

by Esquirol, taken from Andrew Scull’s “Madness in Civilisation” (2016), p226

Over time though, seeing the sparse results of these harsh treatments, a newer philosophy of treating the insane came to be. One that relied heavily on moralism, and considered to be more “humane”. The argument being that fear tactics only trained lunatics like animals to feign the results their jailers desired— actual progress notwithstanding. No, the madman was still a rational being, thinkers argued, and so should be treated as such. And it caught on; even St. Luke’s has a note reading that “The moral treatment of our patients is based upon those benevolent principles which have been so humanely endeavoured to be carried out at other Asylums. We believe that the only question which can now arise is by what method the insane can be treated in the most humane manner”6. Though the definition of “humane” is definitely lacking from our modern standards, that’s for sure, my dear.

It is easy to look at the barbarous slices of known treatments provided to patients as absurd, but it is crucial to remember that madness was not yet entirely believed to be a mental illness. In fact, great importance for the medical field in earning the lucrative right to treat lunacy laid in establishing the various ailments of the mind as somehow physical, and thus within their realm of expertise. The mind was still largely thought of as the soul, and to imagine the soul as able to deteriorate would be unthinkable. Therefore, there was a great emphasis on the brain as instrument of the soul, and open to fallacy without questioning the superiority of man. A solution was found: “Bedlam madness, and the milder forms of melancholy, hysteria and the like, were symptomatic of disorders of the brain or the jangling of nerves.” (Scull, p167)

The term “the English Malady” originated in 1733, collecting all manner of ailments including “Nervous Diseases of all Kinds, as Spleen, Vapours, Lowness of Spirits, Hypochondriacal and Hysterical Distempers” (Scull, p163) under one neat, elitist umbrella. It caught on like wildfire with the upper classes. Nobody wanted to be simply hysterical or hypochondriac, and therefore associated with the vulgar, beastly lower classes. The English Malady, in contrast, was a highly civilised affliction, affecting only the most refined of high society, their sophisticated lives leading to the most sensitive nervous system. The vast superiority of England simply made them more susceptible to various grievances— see, my dear, complaining has always been the British pastime!

Even though the disease was now effectively elevated, the treatments remained largely the same for a while: bleedings, emetics, and strict diets galore. But physicians quickly realised the harm in scaring away their well-paying high society clients with such base treatments, switching instead to milder ones. Changes of scenery, light travel, flattery, prescriptions of opium, and travel to spa towns to partake in the healing waters were all recommended for such cases. This reasoning of madness was both seductive, and reassuring; lunacy was not beyond control, and could be mitigated through rational means. Elsewhere throughout the country, new kinds of moral treatment were undertaken in asylums to “seduce” the common mind away from madness. These facilities did away with their prison-like environments in favour of societal miniatures that aimed to re-introduce the mad to sanity through a microcosm of the world outside its gates, complete with work, self-restraint, and what philosopher Foucalt dubbed “gigantic moral imprisonment” (from “Madness and Civilisation”, 1963).

Despite the period’s insistence that certain types of madness were a symptom of civilisation and thus should disproportionately affect the bourgeois, it was the working class that was over-represented in the asylums. And as the permanent population in asylums grew steadily in the same trend, by the 1850s it became nearly impossible to deny that madness actually affected the lower classes at much greater rates (no doubt due to their harsh living conditions). The classist theory of nerves had in fact created a wider divide between the “beastly” madness of Bedlam, and the mild, flowery melancholia of the wealthy, now separated almost completely from one another. As a result,

“Conditions were if anything still worse in institutions that specialized in the confinement of the mad. […] two of the largest private, profit-making madhouses in London, testified that they were infested with fleas and rats and were so cold and damp that many patients suffered from gangrene and tuberculosis; patients were also grossly abused by the attendants. Beating and whipping were widely employed, and female patients were frequently raped.”

by Andrew Scull, from “Madness in Civilisation” (2016), p191

The horrid conditions of these madhouses did not escape the public, and a new governing body was founded in 1845: the Commisioners in Lunacy. Its purpose was to supervise the lunacy trade, and to pass new laws that mandated licensing and funding for all manner of asylums, both public and private.

The theory of nerves had successfully lifted madness into the realm of the mind, and “Few doubted the proposition that madness was rooted in the pathologies of the brain and the nervous system” (Scull, p216). But it was still hoped that physical symptoms could illuminate the secrets of lunacy. After all, some patients who had gone mad and died had been found to have characteristic lesions on the brain: a yet unconnected effect of pre-existing syphilis infection mistaken for one of madness. Death registers from the Asylum for Idiots 1855-18687 show at least a part of this interest in the physical idea of lunacy, as the vast majority of deaths was followed by a postmortem autopsy, despite their causes of death mostly being attributed to a variety of respiratory ailments like phthisis (ie. tuberculosis), pneumonia, or bronchitis. These inquiries yielded very little results, as one could imagine.

II.IV False Imprisonment

“But the idea of absolute insanity which we all associate with the very name of an Asylum, had, I can honestly declare, never occurred to me, in connexion with her.”

by Wilkie Collins, from “the Woman in White” (1859)

So, the British feared the asylum out of fear that its greed-motivated management would detain them for a pay check, while the Americans feared the asylum as a state-sanctioned prison for the (mainly) criminally insane. In France, the aforementioned lettres de cachet also evoked a mass fear of false imprisonment, though much more politically motivated. Being locked up and mistaken for insane, it seems, is a fear as old as time, and who could blame the Victorians with the looming structures of asylums in view, shrouded in secrecy, or later with plentiful accounts of their barbarousness brought into the light? The disorienting fear of confinement, of being mad, or being falsely mistaken for mad were not irrational in the slightest. There were plenty of cases to back these terrors up. But the largest instigator for them was, quite probably, our beloved Gothic literature.

“Many patients likened the experience [of the asylum] to being confined in a living tomb, a cemetery for the still breathing. Madhouses at this time, moreover, with their barred windows, high perimeter walls, isolation from the community and enforced secrecy, invited Gothic imaginings among the public at large about what might transpire hidden from view. Circulation of these Gothic tales had begun in the eighteenth century as soon as such establishment appeared, and showed no signs of slackening as the numbers of the mad in confinement surged in the nineteenth century.”

by Andrew Scull, from “Madness in Civilisation” (2016), p238

Gothic novels love to falsely imprison its heroines in madhouses, or set scenes there to play off the disturbing chaos of the Other. From “the Distress’d Orphan; or Love in a Mad-House” (1726) to “the Woman in White” (1860), women especially bear the grunt of asylum incarceration, whether justly or otherwise. “Female persecution and imprisonment are of a more modern cast with the asylum replacing the convent and the country house the castle.” (by Fred Botting, from “Gothic”, 1995, p87). Though un-characteristically, in “Dracula” (1897) it is Renfield who gets imprisoned, half-insane and half-foreboding Cassandra of vampire toil and trouble to come.

Speaking of vampires and [false] imprisonment, my dear, one simply must mention “Buffy the Vampire Slayer” (1997-2003). In S06E17 “Normal Again”, one of the show’s most controversial episodes, titular vampire Slayer and main character Buffy is made to believe that the past six years of her life as the Slayer have all been vivid hallucinations on her part, and she has instead been confined to a mental hospital for that time. During the episode, her doctors and mother plea with her to let go of her “fantasies” and return to the “real” world. In the end, Buffy chooses her friends, her eyes glazing over as she resigns completely to the “dream” world. Within the canon of the show, it is intentionally kept open which of the two worlds is the “real” one; whether Buffy is indeed the Slayer, or if she is somewhere in confinement, dreaming up the fantastic escapades of the show. The episode certainly holds up as one of the most frightening ones in the entirety of the series’ eight year run-time, playing right on the fear of one’s own mind.

How can one trust their own sanity, if the madman cannot tell the sane from the insane?

II.V Taking to the Waters

“Who the hell takes the waters in the 21st century anyway?”

from “a Cure for Wellness” (2016)

Hydrotherapy, as we have seen, was employed in real-life as a treatment for madness. As moral treatment was on the decline, treatments focused on the body rose in popularity, even crossing the Atlantic. From cold plunges for the lower classes, to spa towns for the wealthy, “taking to the waters” was recommended for a vast array of illnesses, both physical and mental. In fact, the healing waters of Bath, not far removed from London, were renowned for their supposed restorative properties. The Romans established the town as a spa, and the city kept up this longstanding hydrotherapy tradition, becoming a very fashionable tourist destination for the Victorians. The “water cures” popular at the time involved rapid successions of cold and hot water, and “Turkish baths” which involved massages and steam rooms, followed by a cold shower. Bath is also where the aptly named “Bath chairs” originated; portable standing baths on wheels that allowed a patient to be partially submerged, while being carted around either by a person, or a small horse. They’re a little bit comical, a little bit silly, but the best things always are, my dear.

Incidentally, there is also a personal connection of mine to the healing waters— my hometown of Maastricht, the Netherlands, was both founded by the Romans, and had their very own healing baths (de “Thermen”), the ruins of which are situated not far from my former home. Nowadays, there is unfortunately not much to be seen of the bathhouse, as there are only stone markings on the ground mapping out where the walls would have been, a few metres below what is now ground level. But it’s potent enough for one to imagine a different time.

Hydrotherapy speaks to the imagination: lunacy is linguistically related to the Latin for “moonstruck”. The moon, pulling the tides in and out— why couldn’t it pull the water within us? Why couldn't water be the cure to the human condition? After all, the human body is famously claimed to be roughly 80% water8. The 2016 Gothic horror film “a Cure for Wellness”, also plays with this concept of hydrotherapy, with its very own mad-doctor, extracting the essence of life through a curious form of hydrotherapy involving… eels. Seriously. The film features all manner of treatment, from the aforementioned continuous bath, to sensory deprivation tanks, to the Turkish bath. Historically accurate at the very least. But perhaps not as far-fetched as one would imagine (sans eels, that is). The paper “Hydrotherapy in State Mental Hospitals in the Mid-Twentieth Century” by Rebecca Bouterie Harmon (2009) suggests that the cultural fascination with hydrotherapy is, perhaps, cyclical. If so, are we due for a return to the healing waters? Only time will tell…

II.VI Operating Theatres and the Fairer Sex

“I am glad my case is not serious! But these nervous troubles are dreadfully depressing. John does not know how much I really suffer. He knows there is no reason to suffer, and that satisfies him.”

by Charlotte Perkins Gilman, from “the Yellow Wallpaper” (1892)

A quick note on spectacle: the notion of the medical as private has not always been so thoroughly ingrained in society. The middle and upper classes largely dealt with illness and madness in the family within the house, sometimes outsourcing the latter to private madhouses. It was largely the poor who were publicly institutionalised, or institutionalised at all. For the upper classes “‘every bed-room [was] a possible sick-room.’ Likewise, every woman was a possible nurse. Both the sickroom and the nurse were flexible concepts. […] When illness appeared, the wife or mother transformed herself, and so did the bedroom, for illness was a home-based episode. Until the end of the century hospitals were where the poor went. For the middle classes, illness was something that happened at home.” (by Judith Flanders, from “Inside the Victorian Home”, 2003, p340)

But as the medical field gained importance, and men started taking over what was once considered a woman’s concern (and earning money for it!), sick-care was lifted out of the confines of the home. And though the asylum rapidly shifted through contexts- from prison, to private bourgeois retreat, to a system disproportionately treating the working or lower classes- it certainly carried a much more public dimension than the humble house sickroom. Shelley and Byron visited an asylum in 1725, as if taking a simple sightseeing trip. Courtrooms holding “Inquisitions in Lunacy” were public, attended en masse, and heavily sensationalised by the daily press. The spectacle of madness was popular in opera and in the penny dreadfuls the Victorians guiltily adored, not to mention eagerly devoured and re-digested through the literature of the Gothic. Even treatment as intense as surgery was a semi-public affair, with operating theatres open to spectating surgical students.

One such operating theatre is still available to view right here in London, near London Bridge station, as a museum. The old operating theatre used to be a part of St. Thomas’ hospital, and is the oldest surviving operating theatre in Europe, originating from 1822, pre-dating anaesthesia and open to an audience of up to 200 (male) spectators. Even more fascinating, my dear, is the fact that it was used exclusively for the treatment of female patients.

“Before the arrival of anaesthetics all operations had to be quick, which limited surgeons to only a few procedures […]. These operations were carried out as a last resort to save a patient’s life […]. The mortality rate in Old St Thomas’ was 30%, so with such good odds, many consented to the procedures. The three main causes of death were shock, blood loss, and infection. The introduction of anaesthetics in 1846 was a major breakthrough in the history of medicine. However, because it allowed surgeons to perform deeper surgery that could take longer, it increased the chance of the patient contracting an infection. Before the 1860s, there was no understanding about how germs spread, so as a result surgeons did not make an effort to keep themselves, their instruments, or the operating theatre clean.”

from the official guidebook to the Old Operating Theatre Museum

Women and femininity have had their own extensive history with illness, as previously discussed in letter 15. The English Malady was thought to be “more conspicuous and violent in the Female Sex” because they possessed “a more volatile, dissipable, and weak Constitution of the Spirits, and a more soft, tender, and delicate Texture of the Nerves” (Scull, p164). We have already seen that the female patients of St. Luke’s almost outnumbered the men 2:1, and there is writing from the eighteenth century lamenting the men “sending their Wives to Mad-Houses at every Whim or Dislike” (Scull, p139). Depending on the region, men had the right to detain their wives in asylums under their divine authority as husband9 until quite late into the eighteenth century.

Nowadays the asylum, or even the mental health crisis as a symbol, might bring up a majority of female connections, from “Girl, Interrupted” (1999) to Sylvia Plath, from “Sucker Punch” (2016) to “American Horror Story: Asylum” (2012-2013), and from “Jane Eyre” (1847) to “the Yellow Wallpaper” (1892). The “madwoman in the attic” trope is plentiful. Even in media more commonly associated with men, like superhero comics, the women carry stronger connections to the asylum: it is Harley Quinn who is most often connected to Arkham Asylum, the former employee, rather than the Joker, who was an actual patient. The madman is associated with violence against the other, but the madwoman is associated with self-harm, excessive sexual libido, or plain melancholy (see Archive Source 2): stereotypically feminine traits magnified to make the madwoman into the ultimate victim, the ultimate seducer and threat to male power, the ultimate fragile figurine in need of [male] protection.

To be unstable is the feminine birthright, it seems. At least, if you believe art and literature largely influenced by men. This display of female “fragility” in the madwoman was meant to reinforce the “superiority” of men, who, by patriarchy’s design, are supposed to be the “rational”, “stronger” sex. But it only paints a picture of feminine endurance, of a capability to overcome all the stacked odds that come with life as a woman. Historically, women have had the industry of lunacy weaponised against them, time and time again. The madness of society manifest inside the woman must be overcome in one way or another; it must not be allowed to be used against us, to silence us, to shut us up. The story of the modern madwoman is one of recognising her own power: “You have all the weapons you need. Now fight.” (from “Sucker Punch”, 2016) & “Make your survival mean something, or we’re all doomed” (from “Alice: Madness Returns”, 2011).

“Have you ever confused a dream with life? Or stolen something when you have the cash? Have you ever been blue? Or thought your train moving while sitting still? Maybe I was just crazy. Maybe it was the '60s. Or maybe I was just a girl... interrupted.”

from “Girl, interrupted” (1999)

II.VII Beastly Experiments

“We are born of the blood, made men by the blood, undone by the blood.”

from “Bloodborne” (2016)

To the bourgeois rationality of Victorian England, madness was often equal to beastliness. The most “pure” of the senses, reason, being absent meant that the common lunatic was separated from mankind. Historically, what constitutes a difference between man and beast has been heavily debated: motivated partly by philosophy, partly by fear. Because if the difference, however small, lays only in a reliance on reason, a social contract of civilisation, nature vs nurture, then the brink of beast-hood is always within sight. And little could be more frightening to us civilised creatures.

Allow me to introduce you to “Bloodborne” (2015), my dear. You didn’t think I would journey through lunacy and neglect to mention my favourite video game of all time, did you? That would be, for lack of a better word, madness.

“Bloodborne” takes place in the Gothic city of Yharnam, and slightly beyond. I’ll give you a taste of its elegiac and shadowy lore, with a bit of help from “Bloodborne: the Official Guide” (re-released in 2025). After the shadowy college of Byrgenwerth encounter eldritch gods (“Great Ones”) beyond their understanding, they begin to experiment with enigmatic blood ministrations of “old blood” as a cure-all, founding what is known as the Healing Church. But opinions are soon divided on the implications of the Great Ones. Master Willem, old head of Byrgenwerth, was distrusting of the Healing Church’ liberal circulation of blood, warning its founder Laurence to “fear the old blood”.

And he was not mistaken in that notion. Purported as a miraculous cure, people soon flocked to Yharnam to take part in its legendary blood ministrations. But as an epidemic dubbed the “ashen blood” ravaged the citizens of Yharnam, a beastly scourge ignited that turned them ravenous, feral, and transformed them into literal beasts— a gnarly side-effect of the Church’ rampant blood ministrations. And so, a man called Gehrman broke from the Church to found a society of “hunters”, who made a profession out of systemically eliminating the scourge. They partake in a twisted communion, imbibing the intoxicating blood of their victims to heal themselves, often ending up blood-drunk or beastly themselves. And that is where the interactive part of the game comes in, my dear. The player has come to Yharnam to seek their own cure, and signs on to become a hunter, embarking on a journey that will lay bare the sins of the Church, Byrgenwerth, the Hunters, and the many other factions involved.

And these sins, by the way, are plentiful. In the early days of the church (most likely before Willem left) their Research Hall patients would imbibe water within their heads, until they swelled up with brain fluid: an attempt to create internal eyes, as Master Willem theorised would help them ascend to godhood in the image of the Great Ones. But that is not all. In their quest to cultivate “worthy” blood, the Church also groomed nuns for their experiments, hoping to turn them to “Blood Saints” whose extremely potent healing blood would lend legitimacy to their teachings of man’s ascendance through blood. We meet Adeline, one of these Blood Saints, on our venture into the nightmarish Research Hall, strapped to a chair and with the signature horrific enlarged head of its patients, begging for brain fluid: “The sticky sound whispers to me. So very close, right into my ear.”

The game’s narrative successfully brandishes together a medley of horrors, from Lovecraftian cosmic horror, to the very real institutionalised violence often perpetuated by those in power through medical channels. I have brought it up as a respectful amalgamation of several of the themes we have discussed already: hydrotherapy, institutionalised violence against women, and theories of blood purity. The Victorians’ rickety reasoning as to the significant working class overrepresentation within asylums soon led them down a path rambling wildly about “degenerates”, instigating violence against the disabled, and eventually, eugenics.

The fiction of “Bloodborne” is deeply rooted in real-life accounts; a cycle of reference between history and fiction which, to me at least, enriches each other. Its connections run all the way from Lovecraft, to William Ernest Henley’s hospital poetry as seen at the very start of this letter. “Bloodborne” treats this history with the utmost respect and empathy; horror and shock are vehicles for empathy and awareness. It reiterates what all the history before it has already made evident; dehumanising each other is the gateway to tragedy.

II.IX Final Notes

“Mental illness haunts us, frightens us, and fascinates us. Its depredations are a source of immense suffering and often embody threats, both symbolic and practical, to the very fabric of social order. Ironically, the stigma that surrounds those who exhibit a loss of reason has often extended to those who have claimed expertise in its identification and treatment.”

from Archive Source 3

The reality of madness is that we simply are not as distanced from its clutches as we’d like to believe. We kid ourselves into building an imaginary shield of Ration and Sanity, for the purposes of snobbery, but to what end? As if everybody who has strayed off of the path simply didn't protect themselves well enough, wasn’t moral enough, wasn’t sensible enough. Regurgitating Victorian sentiment. But the truth is that we are not the masters of our mind, not by far. Lovecraft understood this in his writing, in the trenches of his cosmic horror: there will always be things so beyond our comprehension that the very idea of them could drive us mad. So if medical horror is body horror, then asylum horror is sanity horror. Fear of the mind, the wrinkles and workings of the brain largely impenetrable to us.

The power of the asylum as place of horror lies in the fear of the Other (the mad), the fear of False Imprisonment, the fear of the Other Within Us. In the cultural imagination it is a grey place of imprisonment and abuse, horrors laid bare. Meant to evoke cleanliness, it can instead evoke coldness. Its associated interior certainly doesn’t help, with its easily disinfected surfaces and medical look: “anything that is bound up with the body and its immediate extensions has for generations been the domain of white, a surgical, virginal colour which distances the body from the dangers of intimacy and tends to neutralise the drives.” (by Jean Baudrillard, from “the System of Objects”, 1996, p33)

The kind of visibility we have permitted the asylum has not been very generous; and what’s to stop this sensationalist, gruesome angle? We are creatures of morbid curiosity, after all. I promise you Shelley and Byron would not pay a visit to an ordinary hospital, and the Gothic does not write of doctors, except when they abuse their power. But the horror is, also, in many ways, akin to empathy (see Archive Source 2). There is an argument to be made that the spectacle of asylum horror is concerned largely with the patients, with us-as-patients, and not with the doctors that mistreat them. The line between voyeurism and empathy is thin, yes, but it is there nonetheless, and history continually dances on it. Sometimes we land on the better side of it.

“Like the asylum, where truth is frequently cemented into a forced silence of delusion, the excessive and elusive mode of the Gothic is haunted by its irrepressible fetish of live burial and entrapment. Gothic departs from the medical gaze to encourage readers’ empathy with marginalised asylum populations.”

from Archive Source 1

Very little historical firsthand accounts of asylums survive, as Andrew Scull (2016) points out. History is written by the victors, or in the case of the asylum, is written by practitioners in impersonal terms and scattered across databases and archives. Only in the 1900s do we start to see more complete patient files, neatly bundling observations, personal letters, and medical information together. Shame and stigma are what make abuse flourish. Secrecy perpetuates itself within this spiral, abuse begets abuse. In our modern day mental health revolution, we should be actively extending visibility to the psychiatric ward and its patients, taking care to lean onto the side of empathy.

For every ten poorly handled depictions of mental health care, there are a handful more sensitive in their depiction of the subject matter. Some agree with the nuance of “Girl, Interrupted” (1999) in relation to lived experience, some appreciate the horror like “Bloodborne” (2016) which continues to evoke a strong empathetic response. Artist Anna Marie Tendler recently published her memoir “Men Have Called Her Crazy” (2024), focusing largely on her voluntary stay at an in-patient mental health facility. During her intake evaluation she does a Rorschach test, the results leaving her emotional as she is finally met with evidence of her struggle. Validated for the first time as she is in her experience, she begins to cry: “At this point tears begin to fall from my eyes, not because I am sad or angry, but because I have never had these dueling aspects of my personality mirrored back to me in such a matter-of-fact way. I have, at so many times in my life, felt unknowable, but here I am having me explained to me as it feels to be me. One three-hour test and I finally have objective words to demystify a tumultuous and ambivalent life experience.” Her doctor ends the session on an empathetic note, telling her outright how much he feels the weight of her suffering.

“Thank you,” I say, my voice quiet and quivering with emotion. “I really appreciate this.” “Yes,” he says, “I believe you really do.”

III. a New Look

“All the lilies bloomed and blossomed”

by Hole, from their song “Petals” (1998)

The White Lily Society has a new look— a new logo all you eagle-eyed readers and / or social stalkers might have noticed already. Regardless, I wanted to give this new feature a bit of a spotlight, no matter how brief or succinct (though God knows I am allergic to brevity). The new logo was illustrated by the phenomenal Julia Jane Martens and consists of- you guessed it- white lilies and an equally gorgeous matching wordmark. Ornate, delicate, and dreamy, the new logo is inspired by vintage woodcuts, while the thorny lettering is meant to echo our beloved “Sleeping Beauty” story. Julia is one of my favourite illustrators, with her beautiful vintage style and deep understanding of whimsy, so it’s been an absolute honour to commission her for this logo and have it turn out beyond my (already sky-high) expectations!

It’s the start of a new era for the White Lily Society, just in time for our second Substack anniversary on August 1st ☆

✧・゚: *✧・゚:* On the List *:・゚✧*:・゚

Exhibitions, Events, and Talks. It’s a surprisingly calm month for events! Turns out the summer heat (and the probable vacationing) gets to everybody’s head, not just mine. First of all, “Abstract Erotic: Louise Bourgeois, Eva Hesse, Alice Adams” is still on at the Cortauld until September 14th, so take advantage of the opportunity to see this magnificent collection of sculptures all about sexuality, and the body. Similarly, Louise Bourgeois’ masterpiece "Maman" is available to see for free at Tate Modern until August 25th. The 9-metre spider is a work simultaneously imposing and awe-inducing.

Tennis fans can rejoice, as the Championships at Wimbledon are on until July 13th— don’t forget to take advantage of the free livestreams in the official app!

For all my showgirls, the Western themed “Diamonds & Dust” burlesque show is available to see until the end of September, but if you want to catch a glimpse of the incomparable Dita von Teese, you’ll want to book a date from today until July 13th, 14th-17th of August, or the 18th-21st of September. A glamorous night such as this is unthinkable without the queen of burlesque, no?

Finally, if you happen to be around the Rochester, UK area on the 24th, a dear friend of mine- Hallee Wells- is organising a night of poetry and live music sure to be incandescent! Hallee’s poetry is beautifully fragile and visceral, and her selection of accompanying guests is sure to match the vibe. Certainly not a bad way to pass a deep summer night.

Film, Music, and TV. Unfortunately, if you are not of the opinion that summer is the best season, pickings are slim within the BFI’s current menu. There is only one singular screening of interest to note here, the final showing of the controversial erotic film “the Piano Teacher” (2001), on July 10th. But worry not, as Deeper Into Movies has a few heavy hitters on their line-up to make up for the lack of thematically apt screenings, starting with David Cronenberg’s 1996 showing “Crash” on the 12th of July at Farr’s Dalston— psychosexual, sticky, and hypnotising. Approved by yours truly. Or for the lovers of the strange and unusual, there is Guillermo Del Toro’s “Pan’s Labyrinth” (2006) on the 19th, also at Farr’s Dalston. Tickets for both start at £5.

In the Stars. Happy birthday to all the Cancers and Leos out there (depending on when you read this newsletter during July, that is). There is a full moon on July 10th, dubbed the “Buck Moon” for the time when male deer start to regrow their antlers. Perhaps a good time symbolically to step into your own rebirth. Finally, Mars and the moon are set to be in conjunction on the 29th, when you can hopefully catch a glimpse of Mars’ vivid red glow. The red planet is commonly associated with action, desire, and active energy, so create some space on that celestially striking Tuesday and analyse how Mars fits into your chart; what have you been languishing on, and what needs your attention? The best plans are forged in fire, and the summer heat definitely fulfils that criterion.

Obsessive Tendencies: What I’ve Loved Lately

ASOS, COLLUSION tie front top with collar in “white”, [Delicate and airy for the warmer weather], £29.99

MAC, eyeshadow in “Wedge”, [A beautiful smoky-eye shade, famously used on Kristen Stewart in the first “Twilight” film!], £16

Urban Outfitters, Kimchi Blue “Lennon” Linen Top in “Black”, [Somebody take this top away from me, its had an iron grip on me for two summers now…], £39

Heretic Parfum, “Nosferatu” perfume, [A very odd but pleasant scent, leaning vegetal, green, and wet— like cucumber water, dripstone in dungeons, or fresh rain], £112 for a full bottle— samples available from Heretic or from Scentbird for a limited time

Victoria’s Secret, “Very Sexy” Black Thong Rose Lace Knickers, [Black lace 4ever and ever], £18

HMV, “Twilight” Soundtrack on “Mercury” Marbled Vinyl, [For my sanity, I need my imagination to take me colder places during the heat], £39.99

“Pleasure only starts once the worm has got into the fruit, to become delightful happiness must be tainted with poison.”

by Georges Bataille

And on that final note, the thirteenth hour has come to a close. The waters of madness fall and rise, pushed and pulled by the sun and the moon in equal measure. One can always pray for rain, and I do. Feverishly, I do. And in the meantime, my heart rests with all the incredibly brave, strong women I encountered in my research. The ones who didn't quite get their due just yet. Like Nellie Bly, the eighteenth century reporter who went undercover in a madhouse for ten days, and whose report made major headway in American asylum reform. Or Elizabeth Packard, who campaigned for the rights of both the mentally ill and married women after forcibly having to defend her sanity at trial. All the files I read in my research, of women diagnosed with hysteria over common symptoms. A lack of concentration, insomnia, nervousness. Standards which I fear could make a lunatic out of any of us.

Remember that the summer is bound to end soon: it cannot carry on forever.

Affirmations for the end of summer (Repeat after me)

My temperatures are of a normal, non-boiling temperament

I will not fall ill to the sun’s persistent campaign of torment

It is completely normal to feel sun-drunk and moon-drenched

Until my next letter,

With love (and violence),

x Sabrina Angelina, the White Lily Society

Currently reading: “Madness in Civilization: a Cultural History of Insanity from the Bible to Freud, from the Madhouse to Modern Medicine” by Andrew Scull // Most recent read: “Sonnets from the Portuguese” by Elizabeth Barrett Browning

White Lily Society links // Sabrina Angelina links

Take to the waters and cure thyself of boredom! All manner of ailments could be swept aside, with one single subscription to the White Lily Society! Come, become a martyr of deliciousness.

📼 Song of the (past) month: “Wishbone” - Julia Wolf

Full request history: CLA/001/B/07/001 »»» [1890-1930] [City of London Mental Hospital] [Register of Seclusion and Mechanical Constraint]

H01/STPH/C/12/012 »»» [1821-1862] [Saint Thomas’ Hospital Group] [Box of 20 Photographs of the Old Operating Theatre]

H29/NF/B/01/003 »»» [1884-1991] [Normansfield Hospital / Asylum for Idiots, Earlswood] [Register of Patients]

H29/NF/B/02/001 »»» [1855-1914] [Normansfield Hospital / Asylum for Idiots, Earlswood] [Register of Patients Discharged or Died]

H29/NF/B/15/001-003 »»» [1905-1908] [Normansfield Hospital] [Treatment diaries for DF]

H64/B/02/001 »»» [1754-1845] [Saint Luke’s Hospital] [Incurable Patients Book] - Available Online

H64/B/06/001 »»» [1870-1873] [Saint Luke’s Hospital] [Case Book] - Available Online

H64/B/08/01/001 »»» [1935] [Saint Luke’s Hospital] [Case Notes]

H64/B/09/001 »»» [1851-1852] [Saint Luke’s Hospital] [Medical Examination Book] - Available Online

MJ/SP/C/E/0012 »»» [1781] [Court Sessions] [Clipping of an incident involving a young woman poisoning herself]

MJ/SP/C/E/4802 »»» [1831] [Court Sessions] [Clipping of an incident at Saint Luke’s]

London Archives H64/B/01/016

“The physicians' report for the year 1850, with statistical tables for 1850 and the last century.” - link

See above.

London Archives H29/NF/B/02/001

In reality, it’s more like 55-60%

amazing work 🤍 very educational and a perfect dive into the topic, I'll surely read more of your articles as it is the first I've seen!

so lovely to read <3