09. Took an Arrow to the Knee

Literacy, language, and literature combined.

“In March I’ll be rested, caught up, and human”

by Sylvia Plath

01/04/2024, London, UK

My dear,

March, march, march— Oh sweet, desolate March. I spent the first part of the month in a hurry, the middle on trains and in cars, and the end with cotton balls for brains and a flu that could down any fragile Victorian woman with ease. Yes, it is true that I languished. I spent my time draped over couches and coughing up a storm. Call me crazy, but there is always a certain loveliness in sickness, at least the kind that flushes the cheeks and dulls the day’s blades. In fact, quite a good bit of our modern beauty standards (slender form, rosy cheeks, pale appearance, feminine timidity) come from tuberculosis patients in the 18th century1. The more you know.

My days look eye-ache bright and my nights are filled with candlelight, and so my journals are filled with entries like this:

“Journal entry, 24/03/2024, 10:59-ish.

Trying to learn how to journal is like landing a plane or peeling an artichoke with one of your hands burnt off. There are bugs in my carpet and one in my bed and love is a bug too. Don’t you know? A friend recommended I read the Bacchae yesterday and my throat hurts so I may lose my voice (a frightening prospect)

Why can I never do enough?

It feels like my brain is in one language and I’m in the other, nested in between verbs and nouns. I brim with desire but lack activity (and I find it hard to spell in the thrall of writing— please, please, please forgive me). Last night I wept tears of beauty over a Richard Siken poem and here’s some of the notes I woke to:

24/7 heartache (beneficial)

vile dog, shameless charlatan

divine and maddening

cherry-sweet entropy

rat king, wheel of death

They’re just snippets, really. Ingredients.”

This fair March newsletter is all about the Intersection of Love and Violence (isn’t everything?), but specifically the violence of our cultural romantic metaphors. More on that later on. Now I know you have a mind for newness, so let’s see what news there is. There’s a very short write-up about Anna May Wong, an Asian-American actress from the Old Hollywood age. A little bit about Rabanne and those Princess Irulan chainmail headpieces from “Dune Part Two” (2024). We discussed Petra Collins’ photography, and miniature dollhouse crime scenes, and creative [practical] movie effects.

And just in case you get lost along the way, the yellow bricks trip you up and the white rabbits give you bad directions— there is now an ultra-convenient masterlist of all social write-ups, right here on the Substack. Voila, you needn’t get lost ever again! You’re welcome.

I’ll also take this opportunity to remind you of the White Lily Society playlist, which has recently been updated with some fun new tunes, including the song from that Vampire Diaries scene with Katherine, a locked apartment, and a bottle of bourbon. It’s quite a bipolar playlist, really, but I enjoy finding songs that I feel envelop that White Lily Society vibe, whether it’s through lyrics (hello, Intersection of Love and Violence), or sound. Either way, you know where to find it.

Now follow me, follow me, follow me, right down into the pit of madness.

I. Archive Updates

“Since childhood, I’ve been faithful to monsters. I have been saved and absolved by them, because monsters, I believe, are patron saints of our blissful imperfection, and they allow and embody the possibility of failing and live.”

by Guillermo del Toro, from his victory speech at the 2018 Golden Globes, after winning “Best Director”

As promised last month, this month’s newsletter is largely devoted to the sort of knife’s edge that is the violence of our popular cultural romantic metaphors. The language of the Intersection of Love and Violence, if you will. It’s intriguing. We fall head over heels, we are shot by Cupid’s arrow, we get butterflies in our stomachs, our loved ones take our breath away, and we get a crush. Love conquers all. But why does it need conquest? Why draw a blade? Why must we be shattered, or tripped up, or stopped dead in our tracks? That is what we will suppose to uncover, at least partly, today. Starting with some literature, of course.

“Love, Lovesickness, and Melancholia” - link

Examining the love melancholic, the desperate yearner, and the tender mourner, this paper uses examples from classical literature (ie. Ancient Greek and Roman literature) to establish a sort of history of lovesickness. As it posits “love, lovesickness, and melancholy are inextricably intertwined” it uses this hypothesis to examine what it sees as two sides of lovesickness: the depressive side, and the manic side. Melancholia quite literally kills, and some of the descriptions of the lovesick in question do skew poetically beautiful.

“[I] have dwelt at such length on this version of the Medea story because it provides such a detailed (and moving) instance of the violent power of passion. Medea's lovesickness—and there can be no other word for it (she is still a virgin, and a young one at that)—leads her to remarkable acts of violence. In Apollonius' reading of the emotion of lovesickness, the onset of love and, later, its frustration, can lead to violent physical and emotional disorders. It can lead, furthermore, to acts of violence, even murder.”

“Love Speech” - link

Quite a dense read, this paper attempts to look at the specifics of the phrase “I love you”. First, through comparing love speech to injurious hate speech, and then through defining the unique characteristics of love speech. The author ends up defining love speech through (1) singularity, (2) citationality, (3) performativity, (4) asymmetry, and (5) impurity, and in the process brings up a whole host of supporting literature to ignite further investigation.

“Love declarations are not always welcome. Slavoj Žižek calls this the “violent aspect” of love speech, the side of love speech that not only ruptures the self but also interrupts the other: ‘Say I am passionately attached, in love, or whatever, to another human being and I declare my love, my passion for him or her. There is always something shocking, violent in it. […] In no way can you bypass this violent aspect’”

“The Genesis of the Arrows of Love: Diachronic Conceptual Integration in Greek Mythology” - link

Another dive into classical literature, this piece traces back the roots of what is probably the most ubiquitous metaphor of romance: the arrows of love. In comparing the image of Eros the Archer to Death the Grim Reaper, the literature shows how blends of cultural layers and metaphors of human experience can create these now-essential metaphors and anthropomorphisms.

“[…] the arrows of love were the culmination of a long creative process in Greek mythology. Both their invention and their initial success drew crucially on conceptual materials available from early archaic culture: Apollo the Archer personifying the cause of death and mortal disease, his action structured as an emission coming from a deity in a superior position; erotic emissions in lyric imagery; the link between passion and extreme illness, and possibly the arrows of glance”

II. Ensnared by love

"The bear loved the deer, it was obvious. It ripped the deer's throat out, and then licked the dying deer with the most passionate affection. I thought of you and me."

by David Cronenberg, from “Consumed” (2014)

“Desire, I was only beginning to understand […] comes in many forms, and some of them are violent. Struck by an angel’s arrow, or drugged by a loveflower, desire wounds, and I have felt its blue sting. The thought of him all day, like pushing on a bruise”

by Madelaine Lucas, from “Thirst For Salt” (2023)

We have seen that Love and Violence are two magnets, two opposites, that attract. I mean, that is practically what we’re all here for, right? That singular idea is the beating heart of our here White Lily Society. Love and Violence: 17th and 18th century literature were full of it. Courtly love in medieval legends was what tragic romance was to the pre-raphaelites, was what haunted Gothic narratives were to fairytales’ stories of trickery and doom, and all of that nested itself firmly within Romanticism. Which in turn gave root to the way we talk about Love.

In itself, Romanticism is not always primely concerned with, well, romance. No, your mind may first stray to travel writing, to the grandeur of nature, the Sublime. To revolutions and literary protests, to the solitary poet, torturously brooding. But each and every one of those is also motivated by Love, and complicated by Violence. The twin-forces of Love and Violence, pleasure and pain, passion and suffering. It’s that conflicted nature that draws us in, it’s the prism that refracts the light, and entrances us.

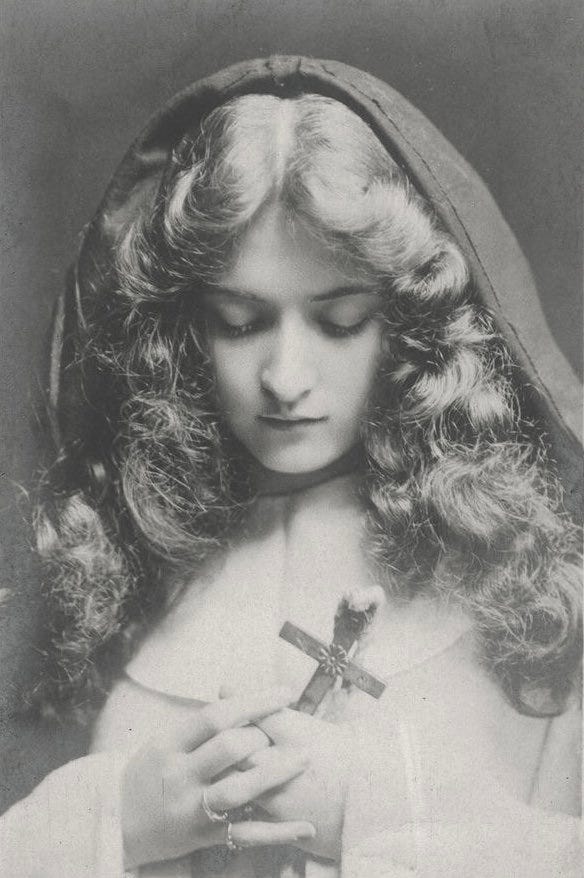

Love in Romanticism is first and foremost an “awareness of the sacred”, an awareness of the holy (The Penguin Book of Romantic Poetry, p. 3). Whatever form Love takes, it is met with quiet reverence and breathless awe— it’s a divine bolt of lighting straight to the soul. And what is sacred is worthy of reverence, calls for sacrifice. Like saints and martyrs suffer, so does the lover. All the obstacles usually between the lover and their loved one only serve to reinforce its religious aspect to them, serve to reinforce Love’s importance. Perhaps that is why our talk of it, of Love, deserves such grand, intense metaphors and idioms.

“I have been astonished that Men could die Martyrs for Religion— I have shudder’d at it. I shudder no more— I could be martyr’d for my Religion. Love is my Religion. I could die for that. I could die for you.”

by John Keats, from a letter to Fanny Brawne (ca. 1819)

Love is irrevocably intertwined with Violence because it has the added power of doing harm: “A profound love between two people involves, after all, the power and chance of doing profound hurt”, as Ursula K. Le Guin writes in “the Left Hand of Darkness” (1969). Bataille agrees too: “The likelihood of suffering is all the greater since suffering alone reveals the total significance of the beloved object. […] Hence love spells suffering for us in so far as it is a quest for the impossible, and at a lower level, a quest for union at the mercy of circumstance”.

And those circumstances are plentiful in Romantic literature and writing, most of them restrictive, obstructive, or even forceful. For every love story’s happy ending, there are hundreds that end in tragedy. Forbidden love, powerlessness, helplessness against society and the depth of emotion— inexperienced love, puppy love, the lamb’s love for the butcher (“He is the tender butcher who showed me how the price of flesh is love”, Angela Carter): these are all prevalent. Romanticism recognises that we are uniquely powerless against Love, which is precisely why it troubles us so.

“When Eros wounds Medea (3. 284-98) the subjection to love is sudden and complete: ‘He [Eros] shot at Medea. […] Her heart was flooded with this sweet agony’”

See Archive Update 1

Sweet agony, then, it is to Love, to desire another so wholly. One might even say Love obliterates the self, it eclipses the self. It’s a little death, potentially repeated infinitely. “Once we are in the habit of oscillating between fear and hope and subjecting every bit of evidence to elaborate consideration, our inner life becomes indissolubly linked to the other [person]. We cannot tear ourselves free. This is love.” (From “Conditions Of Love: The Philosophy Of Intimacy”, by John Armstrong) Perhaps it makes sense then that the French refer to an orgasm as la petite mort, or the small death. Love, and by extension pleasure, is an extended series of small deaths. Because in giving yourself over, you inevitably lose parts of yourself.

“So if there is a lesson to love I think it is this: knowing that one cannot return to oneself, that one cannot go about one’s business as one used to”

See Archive Update 2

Suffering at the hands of Love is considered a divinely beautiful, even sacred, thing. Tortured love is put on a pedestal. We tell stories of it, hushed by the heat of a fire. We paint the most evocative scenes of longing, of tragic love, of martyrs. Paolo and Francesca being almost hypnotised into a kiss, not knowing it will be the end, not the beginning, of them. Isabella and her pot of Basil. Orpheus and Eurydice. The Lady of Shallot. The many trials of Cupid and Psyche. And our language of Love is equipped to deal with this grandiose reverence in return.

But Romanticism also favours solitude, endurance, or a quiet sort of strength found in the lonely wanderer. Perhaps this is also where some of that Romantic (and later, Gothic) ferociousness comes from. Like nature is brutal and beautiful all at once, so is Love through the eyes of Romanticism. And like man is exposed in nature, Love exposes us and strips us bare. It’s Love and Violence again, that extremely contradictory tenderness: it awakens the sensation of being prey, hunted perhaps by Eros himself, not much more than a slave to his arrows of Love. And much like an arrow to the heart, Love is often unexpected, sudden, quick, intense, and crushing.

The Greeks believed in many different types of love, and they had a word for each and every one of them: Agápe for unconditional love, religious love. Éros for love of a more lustful or romantic quality. Philia for loyalty, friendship, and platonic love, and philautia, a love reserved for the self. These in itself do not seem to suggest a more violent side to Love, yet the literature of Ancient Greece most definitely writes about love as if it is starvation, with the reverence of the sacred, with violent, depressive melancholy.

It’s not far-fetched to suggest that the Romantic era influenced the broad strokes of [Western] notions of love: “The depressed, fretting, passive, and physically ill lover (sometimes termed the love melancholic), though present in ancient literature, is more a cliche of medieval and modern literary experience.” (Archive Update 1). The Intersection of Love and Violence has its roots in medieval myth, adapted by Romanticism, and then adopted by culture at large. Swallowed whole and consumed, digested, integrated. Spat back out right at us.

II.II On the Flipside: a Clarification.

It is important to discuss the Intersection of Love and Violence, not just in a literature world of speculation, not just as something we revere to a certain extent, but also the real life implications of such an ideology and how widespread the effects of the language can be. Because as much as we (I) adore the overlap of these ideas, it is always a necessity that we recognise the flaws and dangers of our cultural language. Like the idea most of us were spoon-fed as children that the ones who bullied us did so because they “had a crush on [us]”, real life abuse can and does often fly under the radar because it fits the tortured Romantic ideal our cultural imagination admires.

Thus, I wish to clarify that when the White Lily Society fawns over the Intersection of Love and Violence (mostly in literature) one must keep in mind that this concerns not necessarily a violence against one another in love, but instead violence inflicted upon one or both parties by love itself (as a force of nature). We’re talking about soul-crushing devotion, melancholia, and aimlessness— lovers reaching out with comparable terrors in their hearts. If there is physical violence in the picture, it is usually self-inflicted, the way martyrs suffer for their devotion and dedication. Third parties do also, on occasion, dish out the Violence in that Love/Violence equation, but their contributions are usually not the ones that enamour us, because their Violence lacks devotion, it lacks imagination. Therefore their acts of Violence get sidelined as circumstances, contributing factors in the story. Not the beating heart of the story.

What really grips us is that self-inflicted harm, the way Juliet plunges the blade into her own chest. There is a sort of hypnotising agency to it: even if doomed by the narrative, death does not have to be steadfast on the menu. The choice is not necessarily between poison and blade. But there is something admirable about how single-mindedly the young Juliet resigns herself to her doom. It’s oddly selfless to live or die for something greater than yourself. We envy her ability to envelop herself in Love, because many of us are weighed down by the practicalities of everyday life. We know the bargain: “[…] either we devote ourselves wholly to love, love which is inherently selfless, or we suffer endless disappointment and insecurity”. (From “Conditions Of Love: The Philosophy Of Intimacy”, by John Armstrong). So if suffering is on the table regardless, if it’s unavoidable, the choice lies in how we frame it. And how we talk about it.

This relationship with our own suffering can be oppressive, sure, but it can also be empowering. For women or feminine presenting people, who are traditionally the prey to be chased after, it can be liberating to be the hunter, even if mostly through dramatised yearning or a feverish pursuit of Love. The only way we can break free of being hunted is by hunting. Angela Carter examined this in a different context in her look at the Marquis de Sade’s erotic works, and the function of women within it. She wrote:

“Women do not normally fuck in the active sense. They are fucked in the passive tense and hence automatically fucked-up, done over, undone (p.31).” & “To be the object of desire is to defined in the passive case. To exist in the passive case is to die in the passive case— that is, to be killed”2

So what shall we make of this?‹ Our language surrounding Love is violent, because of Romanticism’s influence on the mythos of our culture. Because Romanticism is what surrounds us. It’s violent because, well, Love itself can be violent. It’s the subject of strong feelings, not meek indifference. It stirs within us like a summer storm. And perhaps that is also a bit of a guilty pleasure, for many people. Perhaps we are just drawn to darkness, or addicted to the sort of feelings that remove us from ourselves. The out-of-body experience that is Love, “eroticism” as described by Georges Bataille: our ever-lasting quest for a continuous experience as discontinuous beings. An eternal reaching for something bigger than us. Love and Violence being those eternal things.

Maybe Cupid didn’t materialise with arrows as much as we put those arrows in his hands. We handed him the bow, and we gave ourselves the words, and we constructed a language for Love that could deal with the reverence we wish to give it. And we let Love and Violence remain intertwined within it, because even if we are lovesick fools in the end, we are most definitely not liars. We don’t intend to lie to ourselves.

III. Literacy, notebooks, linguistic self expression

“We are somewhat defenseless against language, against its forces, because those forces are constitutive of the way we come to define our experience of the world and ourselves. “

See Archive Update 2

Sometimes you just stumble on something that seems to be on the periphery of your interests, something you’re not sure you’ll enjoy, but you take up anyways. This is the story of one such thing.

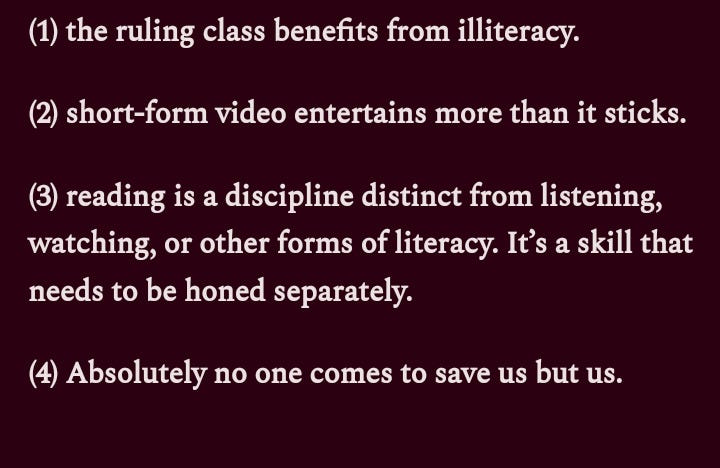

This past March, I listened to “Sold a Story”, a multi-part documentary / journalism focused podcast by APM reports that discusses exactly why there are millions of children [in the US] that can’t read. It was an infuriating experience, one that made my ever so sweet blood boil. It had me rolling my eyes and biting my tongue and raising an eyebrow in quiet despair. And because I agree with Kafka in thinking we should interact with the [media] that wounds or stab us, I wish to pass that feeling around.

Millions of children are having trouble reading. The cause for this issue is that schools are working with materials based on an idea that has been disproven decades ago. This idea is as follows: children don’t need to be taught how to read, because they’ll naturally pick it up like they do everything else. Yeah.

So, why is this idea so pervasive? Long story short, it’s because it has a natural appeal: the idea of teaching children to be passionate about reading and writing, to see them curl up with a book or enthusiastically tell stories, is a pretty idea. It’s exciting. Unlike the science of reading, which mostly swears by phonics, it’s an idea that favours a more unstructured, freeform approach. It’s bright and bubbly and that is unfortunately also why it’s ineffective.

This is a thing in the UK too. The Guardian just published an article last month foreboding that the UK is on its way to a child literacy crisis, pointing to poverty as the root cause. But poverty is only a partial cause. The real root is the way in which we are teaching children to read. In the “Sold a Story” podcast (Episode 4), host Emily Hanford also discusses this: where [US] school districts fail to teach children to read, parents often have to step in with their own time, and costly private tutors, to combat the poison. This is obviously a privilege not granted to children of an economically deprived background. And so, they fall behind. The school system fails them.

The podcast also features a few truly devastating stories of adult illiteracy. While UK adult literacy rates are at a solid 99%, it is important to realise that that still means that:

1 in 6 (16.4% / 7.1 million people) adults in England have very poor literacy skills.

1 in 4 (26.7% / 931,000 people) adults in Scotland experience challenges due to their lack of literacy skills.

1 in 8 (12% / 216,000 people) adults in Wales lack basic literacy skills.

1 in 5 (17.4% / 256,000 people) adults in Northern Ireland have very poor literacy skills.3

III.II What can we do?

I couldn’t imagine my life without reading, without writing, and it saddens my soul greatly to know that there are so many people who do not get to enjoy these things in the same way, because of systemic and educational barriers. If you are burning just as strongly for this story, and you want to do something about it together, here’s just a little bit of how we can use our time, voice, and passion as the White Lily Society to make a change. Because we are stronger together.

Educating ourselves and others - Education is the foundation for all activism. Listen to the podcast (!), and find alternative sources to bolster and broaden your perspective. Talk to people about how they learned to read, how their children learned to read. Read academic papers if that’s what you want to do. But learn, and spread the word so that for every one of you I’ve converted, you’ll convert three people of your own, and so forth.

Donating, Lobbying, and Volunteering - There’s plenty of charities with the sole purpose of fighting illiteracy, whether in children or in adults. One of them in the UK is Read Easy, where you can also sign up to volunteer and help teach adults to read! Volunteering is a great use of any spare time you have lying around, and I can personally vouch to what a monumentally fulfilling activity it is. Especially when it directly impacts people’s lives. Additionally, you can also donate money to a charity if you can’t give your time. Try reaching out to local schools or representatives and start a dialogue about the ways in which their policies teach children to read.

Spreading enthusiasm about literacy !! - Kidnap your neighbour’s children or young relatives in order to read stories to or with them. Get people excited about reading. Join book clubs and lend books to friends and swap books in public. The most radical thing you can do in our current attention economy is to take it elsewhere. Ismatu Gwendolyn has a great Substack post about this, which I highly recommend. It goes into detail about how and why illiteracy can be used to oppress you, and it’s worthy of some thought.

III.III Journaling

And that last point leads me here. This April, I challenge you to keep a notebook, to put pen to paper and write. It doesn’t need to be some big fancy thing, and the words don’t need to be ripest or most succinct. Something simple, small, able to be thrown into a bag or under your bed if you so desire. Infuse it with moonlight and spill drinks on it if you must. But use it to sharpen your mind and improve your attention span, to map out your feelings. Think of Joan Didion, and rearrange some things:

“The impulse to write things down is a peculiarly compulsive one, inexplicable to those who do not share it, useful only accidentally, only secondarily, in the way that any compulsion tries to justify itself. I suppose that it begins or does not begin in the cradle. […] Keepers of private notebooks are a different breed altogether, lonely and resistant rearrangers of things, anxious malcontents, children afflicted apparently at birth with some presentiment of loss.”

by Joan Didion, “On Keeping a Notebook” (from “Slouching Towards Bethlehem”, 1968)

“Yes, I deserve a spring. I owe nobody nothing”

by Virginia Woolf

Where I am now, I have a striking feeling this newsletter is just my little magpie me, bearing my trinkets to you. Look, behold what I’ve collected. Everything is laid out for your perusal. All my silvered reading and shimmering obsession, my musings and rambles, my wordplay and my ever-expanding web of references. As I write, my dad texts me picture updates of a swan nesting back home, Elvis is playing softly, the sun is warm on my face. All is well. Peaceful. Except for maybe a cough or two, but that will hopefully pass.

Until my next letter,

x Sabrina Angelina, the White Lily Society

Currently reading: “Young Romantics: The Shelleys, Byron and Other Tangled Lives” by Daisy Hay // Most recent read: “the Stolen Heir” by Holly Black

White Lily Society links // Sabrina Angelina links

If you can read this that means you’ve been selected to join us! Congratulations on this once-in-a-lifetime offer. Come, become a martyr of deliciousness. Join the White Lily Society today.

Ps. the title is of course a partial reference to Cupid’s arrows, but also to the iconic Skyrim dialogue line below, and a Kiki Rockwell song. Talk about layering your references.

For more on this I recommend a book called: “Consumptive Chic: A History of Beauty, Fashion, and Disease” (2017) by Carolyn A. Day

See “The Sadeain Woman, and the Ideology of Pornography” (1978) by Angela Carter

All stats from the National Literacy Trust, see literacytrust.org.uk