10. Byromania

We're in the double digits now, baby!

“April is the cruelest month, breeding lilacs out of the dead land, mixing memory and desire, stirring dull roots with spring rain”

by T.S. Eliot, from “The Waste Land” (1922)

This month’s newsletter contains an image in section III that may be disturbing to viewers sensitive to images of bugs, death, or decay. The image is of a waxen vanitas depicting a statue that is half-skull, half face, with insects crawling on the skull side. Reader (viewer) discretion is advised.

01/05/2024, London, UK

My dear,

I’ve officially carried the newsletter to term! Nine “gruelling” months later, and look at the spoils, behold my achievements. Who could’ve envisioned this? Who could have foreseen it? Who could have dared dream it? Surely, if you grabbed your crystal ball nine months ago you could have sworn you were losing it! And yet here we are. My tortured poets, my ragged Romantics, my fellow martyrs of deliciousness— what merriment to be here!

April has certainly been eventful. Cold, rainy, delicious. A little flippant when it comes to weather, but that’s only understandable. We all have our moments, no? For me, it’s most certainly been a wildly thrilling ride. There’s been love and loss aplenty. But despite my actual suffering (spending a week without broadband), I have dragged myself here to present you with my life’s work (this newsletter). You’re very welcome.

Suppose you’d be asking about what’s new around these corners, here’s the list you would be presented with: submissions are now open for the White Lily Society for art, writing, and other afflictions— you can find the detailed submission guide here. Furthermore, there’s write-ups about the use of AI in Go, Tracey Emin’s contemporary art piece "My Bed", and a eulogy for our good Lord Byron, who is, of course, the focus of this month’s here newsletter.

Now, now, let’s continue along. There are far too many sights to take in to dawdle. I promise I won’t bite, only write. Letters can’t bite anyways… or can they?

I. Archive Updates

“You are secretive, kind, and you are passionate and at times unfair.”

by Albert Camus, from his notebooks (1951-1959)

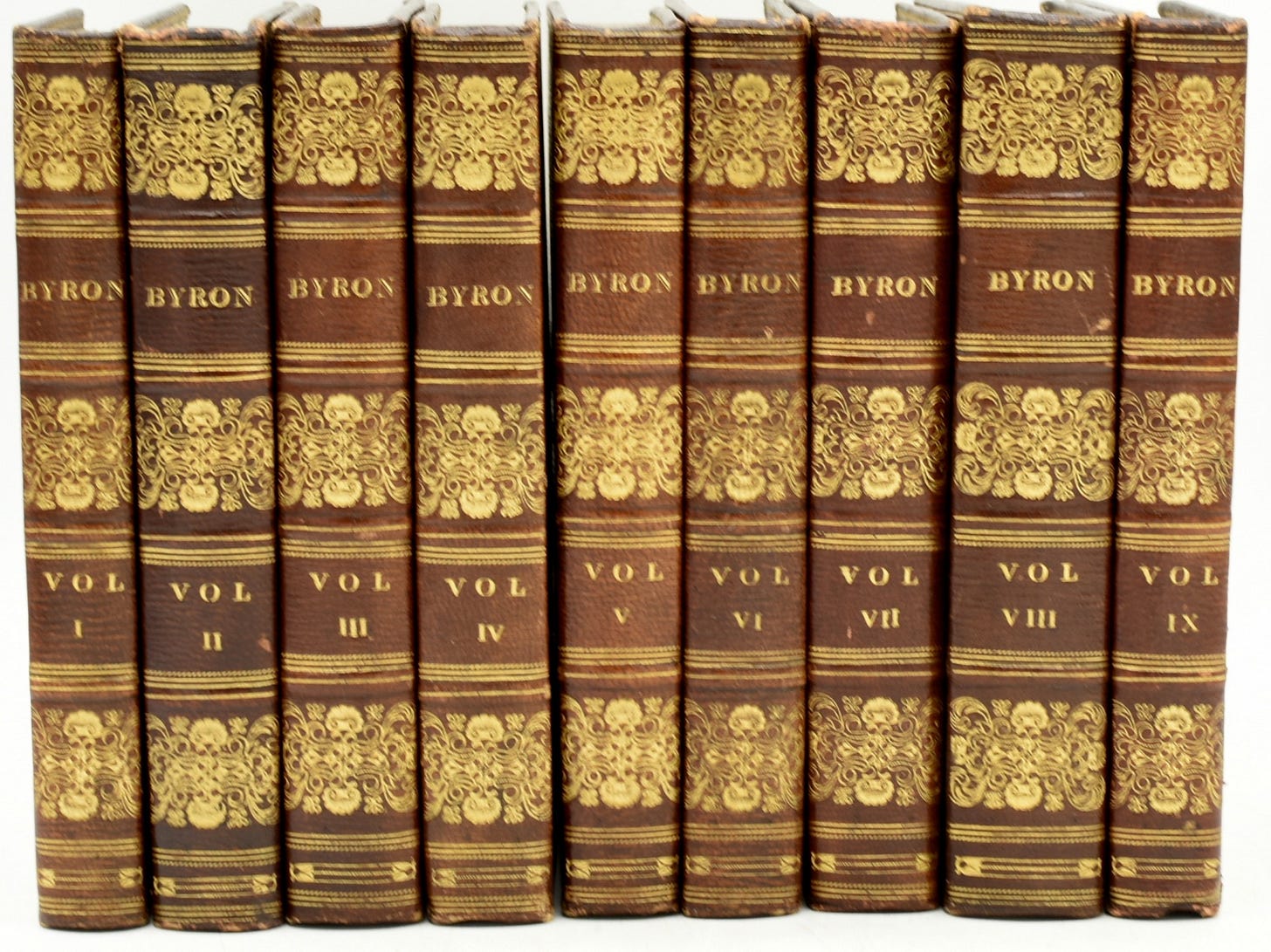

In truth life is all about the tension between a girl and the centuries-big age gap between her and her celebrity crush. It’s been exactly two-hundred years and eleven days since Lord Byron lost his life, but there is scarcely a week where I don’t think of him. The man just has a way of weaselling into one’s psyche (as this newsletter will undoubtedly prove). Last year, I [in]famously declared that I would forego with traditional resolutions and instead just have… Lord Byron. Those who get it, get it. Because if anyone is all about intrigue, it’s him. Take it from me, I’ve done all this research, read all these books and poems, and gone to all these lectures and memorials, just to feel closer to someone so fascinating who is long gone. I guess this is all the Byromania1 talking (writing). But I suppose you’ll see for yourself. Draw up your own judgement, and maybe learn some new delights about Lord Byron along the way. That’s the deal, at least.

“Lord Byron and the Invention of Celebrity” - link

Quite an easy read, this paper talks a little bit about Lord Byron’s celebrity and the influence this had on his writing. Byron was, after all, “the first European cultural celebrity of the modern age” as this paper states— Goethe dubbed him “the first modern poet”. Beyond notoriety, it was Byron’s very own life, his personal scandals and private affairs, that drew society to his works. The same way- and forgive me if you find this comparison crude- fans scour over Taylor Swift’s lyrics whenever she releases new music, looking for clues, pieces of her embedded within her work. Lord Byron was a figure of intertwined “personal celebrity and literary reputation”, and his writing was as famous for its quality as for the latent self portrait it diffused in between the lines of verse.

“[…] canto 3 [of Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage] establishes the groundwork for the modern idea of celebrity. It resides in the wish of the reason public to derive meanings from a work of art in large part because of the way that work represents the life of the artist to engage with, one might even say to manipulate or exploit, that consumer demand.”

“Hero with a Thousand Faces: The Rhetoric of Byronism” - link

Examining the way in which Byron inserts himself in his texts (mainly from 1816-1824), this paper looks at the way his writing functions as masks or masquerade for the author’s own self exploration. There’s a clear thumbprint of Byron in each of the works at hand here: “Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage” (1812-1818), “Don Juan” (1819-1824), “Manfred” (1817), “Sardanapalus” (1821), and “Cain” (1821), and the author is not shy at looking exactly how this broken mirror reflects the man in front of it.

“Personal elements are forced to operate at an unconscious level, Byron's work uses masquerade as a device for breaking down the censors of consciousness. Particular readers are called into the texts by Byron's constructive imagination. As a consequence, Byron, or rather, Byron's textual seductions and manipulations become the principal subject of his own fictions.”

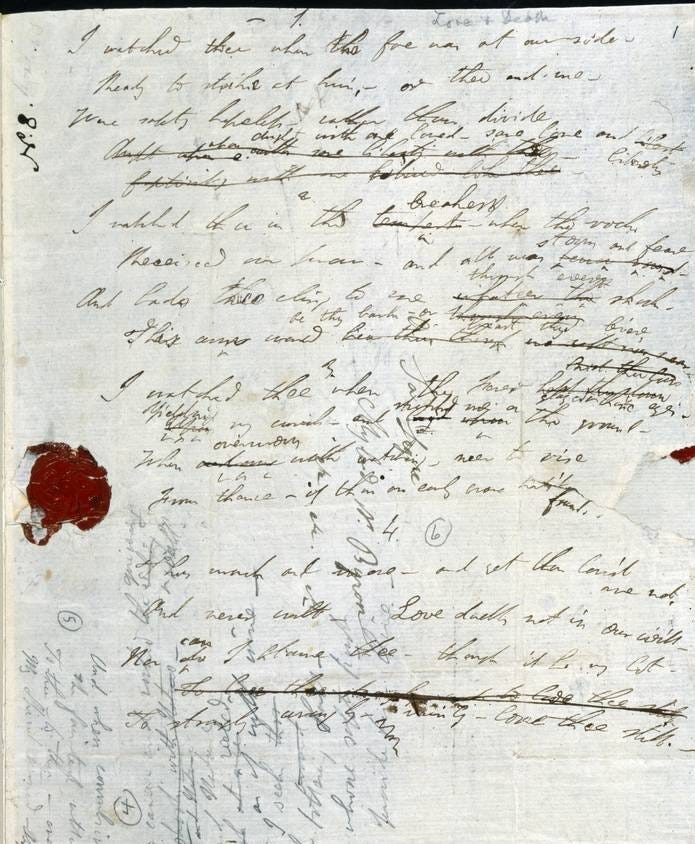

''A Being More Intense'': Byron and Romantic Self-Consciousness - link

More of a dense read, this paper analyses some of the poetic self awareness in Lord Byron’s writing, taking the form of meta-writing, fourth wall breaks, and explicit awareness of the pen writing the poem as we read it. That Byron puts a great deal of himself in his writing we have seen previously, but here it takes on a more human side, as if Byron writes to capture the moment, but keeps stubbornly encountering himself in his own texts. Byron is, even in the fact of writing, in conversation with himself, the narrative, and the future reader, and he likes to make this clear by drawing the curtain back at times: “Few poets are more alive to the fact that the self often to its discomfort- is enmeshed in the social and the historical.”

“[…] and it is intriguing that the philosopher David Hume highly regarded by Byron, described the self as a ‘bundle or collection of different perceptions’ and the mind ‘as a kind of theatre, where several perceptions successively make their appearance’”

II. Mad, bad— you know the drill!

“Lord George Gordon Byron was five feet eight and a half inches in height, had a malformed right foot, chestnut hair, a haunting pallor, temples of alabaster, teeth like pearls, grey eyes fringed with dark lashes, and an enchantedness that neither men or women could resist. Everything about him was a paradox, insider and outsider, beautiful and deformed, serious and facetious, profligate but on occasion, miserly, and possessed of a fierce intelligence trapped however in a child’s magic and malices.”

from “Byron in Love” (2010) by Edna O’Brien

II.I Background (and bears…?)

You might know him only as the great wandering poet, and you might know him only as the scandalous seducer, drinking wine from skulls and engaging in pistol duels. But Lord Byron is one of those enigmatic historic figures one could never hope, or begin, to narrow down to just one thing, one carefully selected phrase. It’s hard to explain why he’s been so prominently positioned in my mind as a “parent” of the White lily Society without looking intensively at his writing, his life, his scattered web of influence, but that is exactly what we shall endeavour to do today. Oh, how to do justice to such an enigmatic, flippant, contradictory figure?

The very definition of “cannot be pinned down”, Byron seems to almost have taken some devilish delight in being a contrarian, in making people guess. His life as a “wanderer, lover, libertine, [and] freedom fighter”2 was ruled by whim and obsession, by passion and cruelty, by our beloved Intersection of Love and Violence. He was an aristocrat who despised much of proper society, and of politicians. A man who cared little about others’ judgement, who put pleasure over self-restraint. But he was also brooding, controversial, more than a little arrogant, particular, and oddly insecure at times.

There was a lot of darkness in Byron’s life, especially in his childhood. Beyond there being evidence to suggest he might have been abused as a young boy, growing up there was basically no stable male influence for him to look up to. Instead, there was a heritage of family madness, on both sides. On his father’s side, there was a string of violent insanity, the same one accredited to his father “Mad Jack” Byron and his grand-uncle the “Wicked Lord of Newstead Abbey”. And on his mother’s side, a string of gloomy suicides. It’s easy to imagine the weight of this history pressing down on the young Byron. Either way, that sort of a legacy of mental illness is not a desirable one for any young child to inherit, and Byron did feel that legacy keenly, even if he would go on to write that “sorrow is knowledge” in “Manfred” (1817).

“As to my sadness - you know that it is in my character – particularly in certain seasons. It is truly a temperamental illness – which sometimes makes me fear the approach of madness – and for this reason, and at these times I keep away from everyone.”

Lord Byron, from a letter to Teresa Guiccioli

Despite his arrogance and his brilliance, there is also an undeniable streak of insecurity throughout a lot of Byron’s behaviour, a kind of anxiety. Born with a major disability in the form of a clubfoot (then seen as a sign of the devil), Byron felt he had to fight twice as hard to be as good or better than his peers. And so, he did. He was a fast swimmer, and a diligent boxer, and for the better part of his time studying at Cambridge he was in the throes of an eating disorder and obsessed with remaining lean: he infamously exercised in multiple heavy fur coats, followed a mostly vegetarian diet, fasted for long periods of time (excluding wine), and drank shots of vinegar.

And yet this need to prove himself did not extend to the entirety of his social and academic life. No, when Byron inherited the title of “Lord” at age 10, he slipped into the peerage like one of his fine coats, though perhaps just pleased by his newfound importance. Later at Cambridge, he gambled and made a great deal of friends, to whom he was generous, clever, and outrageous in equal measure. He published some early poems of his (to cutting critic reviews). And he famously kept a pet bear because his dog was deemed too vicious for the university, but the rules did not state that bears were forbidden to keep as pets. When Byron graduated, he tried to argue that the bear should be given a fellowship for attending his classes with him, though that request was promptly denied. So much for the scholarly bear.

II.II Byronic brooding romance

“…there never was a man who gave up so much for women — and all I have gained by it — has been the character of treating them badly” // “[You accuse] me of treating women harshly — it may be so — but I have been their martyr. My whole life has been sacrificed to them and by them”

from a letter to Douglas Kinnaird | from a letter to John Murray (both taken from “Lady Caroline Lamb: a Free Spirit”, Antonia Fraser, 2023)

More than anything, Byron’s romantic life was riddled with sex and scandal, affairs, and great passionate romances, both with men and women— though for obvious reasons, the female lovers were the main topic of conversation at the time. Byron loved women. Especially married ones. As well as (controversially) his half-sister, Augusta Leigh, who he may have even gotten pregnant. In many ways, he considered her his twin flame. I suppose you can see how the high society rumour mill never got tired of discussing Byron’s latest escapades, real or not. And while he had many conquests to discuss, I will be spotlighting only two of my favourites here (for fear of driving you insane, or short-circuiting your brain with information).

It wasn't that Byron appealed to women in spite of his horrible reputation, no, it was because of it. He was handsome, yes, and a famous poet: everybody whispered about him, everybody knew and spread stories of him. Was he really like the protagonists of his great poetry, brooding and damaged? What had made him this way? Was he really the devil incarnate, what sins was he hiding? It was the paradox of him, both charming and cruel, brooding and arrogantly flamboyant, that intrigued women. He went his own way at all costs: “He became the lightning rod for women's unexpressed desires; with him they could go beyond the limits society had imposed. For some the lure was adultery, for others it was Romantic3 rebellion, or a chance to become irrational and uncivilised. (The desire to reform him, merely covered up the truth— the desire to be overwhelmed by him)” (from Robert Greene, “the Art of Seduction”, 2001)

When Byron met Lady Caroline Lamb in 1812, she had just married, and despite having married for love, her strong love of personal freedom was hampered in living with her in-laws, with little privacy, and her newfound boredom as a wife. She and Byron first made contact very briefly at a ball, after she had sent an anonymous letter to the poet praising his latest work (“Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage”). To his surprise though, upon laying eyes on him, she turned on her heel and left the room without introductions. “That beautiful pale face is my fate” Caroline noted in her diary after the event, but it was overshadowed by the more pleasing phrase describing Byron as “mad, bad, and dangerous to know” that really caught on throughout the ages.

Byron later returned to visit Caroline at her home, and he was immediately captivated. “Caro” had a childish whimsy to her, and an outspoken daringness. He called her his “little volcano”, and the whole passionate affair lasted about five months before Byron started to lose interest (or he might have gotten frightened by Caro’s wish to run off and elope). But she was not so easily swayed. She would dress up as a page to enter access into his apartments, forged his signature to defraud his agent into giving her one of his miniatures (a small portrait), and she sent him a lock of her pubic hair— all behaviours that both repulsed and fascinated Lord Byron. At one point she burned effigies of him on a bonfire, the buttons on its garments reading “ne crede Byron” (don’t believe [him]), a bastardisation of the Byron family motto “crede Byron”.

But perhaps most theatrical of all, there was “ye olde dagger scene”4. At Lady Heathcote’s ball, a few months after Byron had moved on, the little volcano and her ex-lover crossed paths once more. Accounts from here on out differ wildly, but I shall try and get the gist across. You see, Byron was not a fan of the waltz, which at the time was all the rage. Byron, because of his clubfoot, did not wish to partake in the dance and he forbade Caro from it when they were together. This was probably a source of contempt for her, because on meeting again at the Heathcote ball, Caroline made a smug remark about finally being “allowed to waltz now”, to which Byron allegedly insulted her dancing abilities. Caroline then broke a glass, pressed the sharp edge of it to Byron’s hand, telling him she “intend[ed] to use it”. In response, Byron looked at her, unamused (I like to imagine he shrugged), went “On me, I presume?” and simply turned around and left the room. Lady Caroline went upstairs and threatened to kill herself with the glass, before being talked down by some of the attendees. Nevertheless, blood was shed, and both Byron and Caroline accrued more scandal— and in rather a deliciously dramatic fashion, no?

There was Claire Clairmont too, Mary Shelley’s stepsister. She too introduced herself to Byron through a daring anonymous letter, and a very scandalous one at that, practically giving herself to him freely:

“If a woman whose reputation has yet remained unstained, if without either guardian or husband to control she should throw herself upon your mercy, if with a beating heart she should confess the love she has borne you many years, if she should secure to you secrecy and safety, if she should return your kindness with fond affection and unbounded devotion could you betray her or would you be silent as the grave?”

From a letter to Lord Byron by Claire Clairemont (1816), taken from “Young Romantics: the Shelleys, Byron, and Other Tangled Lives” by Daisy Hay (2011)

Claire and Byron had a short-lived passionate affair, which ended up with Claire pregnant. They were a match bound to get on one another’s nerves: she, a young woman not very knowledgeable about society and constantly feeling like a third wheel in her stepsister’s marriage (Mary, Percy and Claire all lived together and traveled together), and he the most famous poet in the world, with a cruel streak. It must have been a most thrilling, exhausting affair, especially for the young Claire, who adored Byron (“Do you know I cannot talk to you when I see you? I am so awkward and only feel inclined to take a little stool and sit at your feet”, letter ca. 1816). But she was overenthusiastic, and even clingy. Byron, meanwhile, most likely saw the whole affair as nothing but a summer’s entertainment, and he wrote about it in the same vein: “If a girl of eighteen comes prancing to you at all hours- there is but one way” (letter, 1822). Ouch.

Despite everything, I do not see Byron as misogynist. Far from it, in fact. While there are most definitely pieces of writing that could be used to paint him in a less than favourable light (Like the joking “You know I hate women”5), there is simply far more evidence to prove that Byron, above all, was a man ruled by passionate, lightning-quick love affairs, and an at-times avoidant attachment style. Yet there is no denying that Byron could and did acknowledge female intellect. He humorously described female wit as a “dangerous thing”. And he liked intelligent women, and sought them out. Not just as lovers, but as friends: I could continue on for entire paragraphs about his friendship with Mary Shelley, or the fact that he respected Lady Caroline’s mother in law Lady Melbourne as a close friend and confidante.

Love to Byron was like the “never dying worm that eats the heart” from Frankenstein (1818). It awakened in him both a capability for great Romantic gestures, and occasional cruelty. It was both a source of passion, and of pain. You might even say it was… the Intersection of Love and Violence. And you know, my dear, that’s exactly what the White Lily Society is all about.

“You should not have re-awakened my heart, for (at least in my own country) my love has been fatal to those I love- and to myself”

By Lord Byron, from a letter to Teresa Guiccioli

II.III Men used to die in war

More than anything, Byron’s writing and actions take a firm stance in championing personal liberty. Freedom of speech, freedom to be at odds with society (something which Byron of course was very familiar with) and freedom to love. When the loom-breaking luddites of 1812 were said to be condemned to death, he made his maiden speech in the House of Lords in an effort to save them, though he didn’t succeed. He empathised with revolutionaries, most famously Napoleon, and went as far as to going to Greece in 1823 to aid them in their fight for independence from the Ottomans: a cause that would eventually bring about his death.

On the 19th of April, 1824, Byron succumbed to a fever on the Greek island of Messolonghi. Greece was a complicated matter from the moment his boat touched shore. Having expected to find some semblance of an organised military force, he instead found a substantial amount of local warlords, all fighting each other just as much, if not more, than the Ottomans: Byron himself noted that there was barely a united Greece. Still, he saw it through. He sold his estate to arrange funds for the revolutionaries, gave orders, and oversaw a small army of thirty officers and two-hundred soldiers. By April, the island was tormented by torrential downpour, and Byron was going stir-crazy sitting inside. He loved to ride, and against all senses, took his horse and did so while the rain was still pouring down. It was a decision that would cost him greatly. Byron returned, rain-soaked to the bone, and with the beginnings of a fever. His doctors, meaning well but ultimately overdoing it, bled him to an excess and worsened his condition in return. Despite their best intentions, the fever took Lord Byron.

In some macabre twist of fate, Byron’s death for the cause gave legitimacy to the Greek revolution. Governments were still (understandably) itchy about revolutions at the time, treating them as if they were some contagious disease that must be avoided at all costs. You know, knock on wood, keep six feet distance, and crush any notion of it, whether spoken or acted on. But Byron’s death in Greece (which could easily be portrayed as a martyr’s death, the death of a poet in exile) gave immense amounts of publication to the Greek revolution. After all, he was one of if not the most famous man in the world at the time, something which cannot be underestimated. Byron practically invented the notion of a “celebrity”, and him dying overseas caused a great ripple effect in the [Western] world.

Today, he is recognised as one of Britain’s greatest poets. His work, his writing, is complex and layered, and established a new kind of Romantic mode: that of the Byronic hero. Lady Caroline Lamb eventually found her own way to the pen, writing a thinly-veiled “fictional” story about Byron, who spared a line reviewing it in a letter of his: “I read ‘Glenarvon’, too, by Caro Lamb; God damn!” (letter, 1816). It was Claire, Mary and Percy Shelley, Byron, and his doctor John Polidori who were all at the Vila Diodati in 1816, from which both modern vampire myth6 and “Frankenstein” (1818) originate. Claire’s daughter with Byron, Allegra, ended up dying of an illness, but not after an extended custody battle which put her mother through hell. Don’t even get me started on all the ways John Keats, Shelley, Byron, and Leigh Hunt’s lives connect, and all their writing in one way or another as a result. I could go on for ages.

Instead, let me leave you with this: Lord Byron left one direct legal descendant (not counting Augusta’s daughter which was allegedly fathered by him), Ada King, countess of Lovelace, through his short-lived marriage to Annabella Milbanke (Lady Byron). The pair had a messy separation and custody battle, resulting in Annabella’s insistence that Ada, under no circumstance, be a poet like her father. She didn’t. Instead she focused on mathematics, and she became the first person to recognise the applications of computers beyond just maths. Some have even referred to her as the first computer programmer. And that, my dear, is how you ended up reading this little ‘ol newsletter of mine. So all the misadventures, all the scandal, all the trials and tribulations— maybe it wasn't all mad and bad, after all.

III. April Recap

“I shall live on dreams because reality is too cruel for me. I think I shall be the kind of person that nobody understands”

by Anaïs Nin

During particularly eventful months I like to capture a few of the things I did, exhibitions I saw, and other obsessions of mine right here in the newsletter. Part manic scrapbook, part tea-time chat, and part captain’s log in which (hint hint) the captain is me, the journal is this very newsletter, and the sea is my soul. So light a candle, pack some provisions, and pray we don’t get lost in it.

III.I Byronic Escapades

If you’ve been hanging around the grapevine talking to little birdies, you might have caught wind of the fact that this April 19th was the 200 year anniversary of Lord Byron’s death. And that of course, prompts remembrance from us here Byronic enthusiasts: turns out there’s quite a lot of us here in London!

I had the wonderful opportunity to be a part of a private ceremony at Westminster Abbey and a dinner at the House of Lords, organised by the UK Byron Society for the bicentenary of Lord Byron’s death— and it was intoxicatingly marvellous! Really, who could complain about dinner, drinks (very Byronic), and good company, in the most beautiful of Gothic surroundings? Believe me, the setting went way more to my head than the wine. Although they did keep refilling my glass when I looked away… so who knows how much wine was actually consumed? For all I know that one glass of champagne could have been three… And yet the blisters from my platforms were minimal, the food overwhelmingly good, and the White Lily Society gained some new members, so who am I to complain?

The day before, I attended the “Byronic all dayer” at the British Library: almost nine hours of lectures on Lord Byron. Some people would shudder in fear at the thought, but clearly not me. That’s in part because there is something seriously wrong with me, but I digress. Nine hours of lectures— but there was a break with wine as well (I’m sensing a theme), and I went home with roughly eight pages of notes and a rejuvenated Byron obsession, something which I have poured back into this letter.

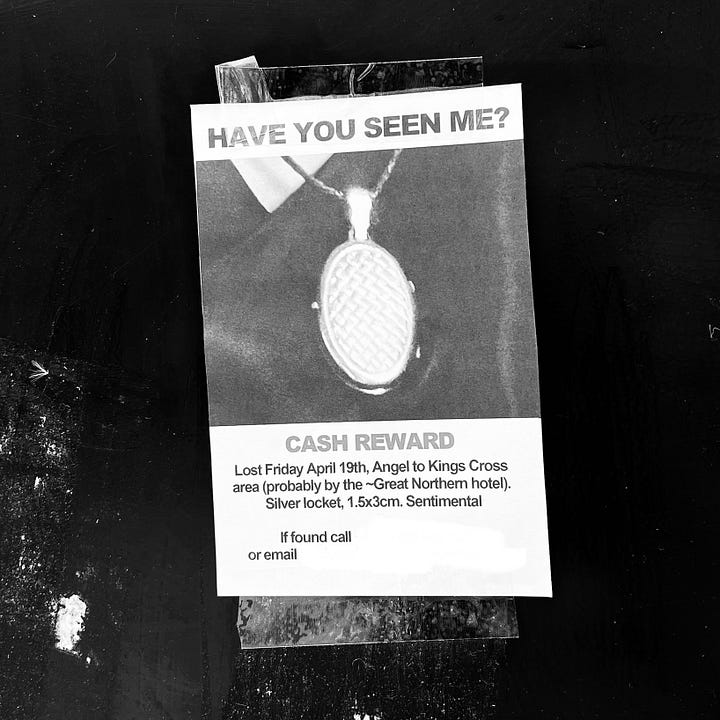

Of course, you cannot have such high highs without low lows to match. One thing not as exciting was losing my grandma’s locket at Kings Cross station. Ironically enough, I had put a picture of Byron in my locket for dinner the day before, and then the next day on the actual bicentenary, Byron decided he had had enough, and he decided to flee this mortal plane once more, two-hundred years down the line. Maybe it was tempting fate too much. Either way, I can safely say it is not because of my doing that I lost the locket (I’m very obsessive with my jewellery: double clasps, constant checks, etc.). I’m crushed, of course, but considering it might still show up, not entirely flattened just yet. As Ethel Cain sung: “If it’s meant to be, then it will be”. Besides, the idea of my locket residing in some proud magpie’s nest does bring a small bit of comfort to my soul. Maybe it made one sewer rat very happy, and very glamorous.

III.II Exhibition(ism) and Other Insanities

Life is always substantially better if you have a (1) a topic to obsess over, (2) a specific piece of art lodged in your brain, and (3) a cluster of words sitting heavy in your mouth at all times. To speak plainly, I wish to be occupied, and feel occupied. Those are two entirely different things entirely, I fear.

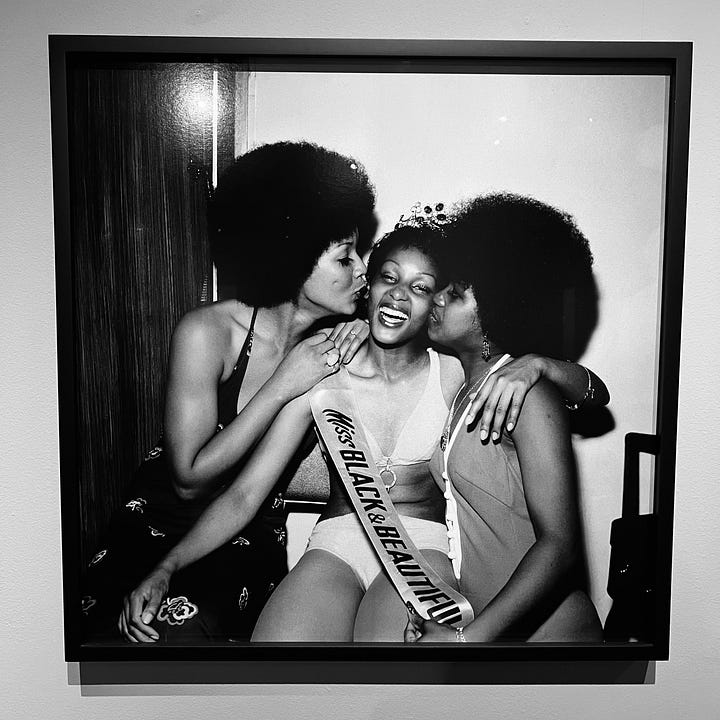

One (or rather two) of the things occupying prime real estate in my skull this past April were the two exhibitions I saw this month: “the Cult of Beauty” at the Wellcome Collection, and “Women in Revolt!” at the Tate. The first was a salient, diverse look at beauty culture which featured a lovely vanitas that promptly grabbed my attention (and brought me back to thinking about anatomical venuses).

“Vanitas, Latin for vanity, refers to a genre of artworks that conveys the inevitability of death and the emptiness of worldly pursuits, notably beauty. This 16th-century etching makes an overt moral judgement on the quest for beauty and wealth. The image reflects conflicting beliefs in Europe at the time, where beauty was seen as the outward expression of a virtuous character but cultivating personal beauty was condemned as hollow vanity.”

From the exhibition text, “the Cult of Beauty” at the Wellcome Collection, London (2024)

The latter, “Women in Revolt!”, while being another super long exhibition, proved to be much more inspiring than expected. Really, feminism, activism, and art are a perfect combination. This is also why, if I’m in the area, I like to look at the zines at Housmans by Kings Cross for the same reason: these are examples of radical ideas, paired with innovative and creative visuals. Contemporary art does hold a special space in my heart as being one of the first art movements I could connect to, a sort of gateway drug, and this includes the host of photography, crafts, and pamphlets that were featured in this exhibition.

From time to time, I also like to update on my resolutions, so hereby: my reading goal this year is exactly lagging one book behind (classic me). But remember when I said my book resolution was dragging back in February? Well, I increased it! From 35, to 40, and now 52. So really my being behind is me… being ahead? It’s a glass half full / half empty kind of situation, my dear. As for films, predictably, that goal is running way ahead of the charge. My favourite of the past month was undoubtedly 1994’s “Interview with the Vampire”. I must confess, I’m a little upset with you for not telling me to watch this film sooner. All this time, I have been wandering the world, so clueless. Just two hours and three minutes away from enlightenment. Oh well.

III.III a Tiny Word of Thanks

Alright, alright, I promise not to drool on you too much in this section in case you get whiplash from the previous scolding, but I just wanted to take a little paragraph to remark on some White Lily Society milestones, many of which have been so amazingly and intoxicatingly sweet. First of all, we reached 101 subscribers on the Substack, and 600+ Instagram followers. It will never cease to dazzle me that people are interested in the White Lily Society, and that they identify with it, that you all have even a grain of interest in what I have to say or share. The past month has been particularly overwhelming on this front, as I finally secured a domain for the site (hello, thewhitelilysociety.com!), and I have been reading all of your soul warming messages as they come in, telling me you love what the White Lily Society is up to. It’s a great honour to be your chairwoman / cult leader / sacrificial lamb, really, and I hope that we all can continue platforming small artists, spreading accessible art education, and forming a welcoming community for new people to get into art. Forevermore.

“Your handwriting. the way you walk. which china pattern you choose. it's all giving you away. everything you do shows your hand. everything is a self portrait. everything is a diary”

By Chuck Palahniuk, from “Diary” (2003)

So, here we are, at the end once more. I confess I often think about what a life would be like where I don’t obsessively shove pebbles into my pockets, or crouch down to look at leaves, or talk to pigeons like a madwoman. A life where I might keep my ramblings contained and concise. But I have concluded that to stop being mad is to cease living at all. It’s madness or nothing, baby! It certainly was some kind of madness thinking I could write about one of my favourite subjects in the world (Lord Byron) and keep it brief. Now that was simply insanity. Having spoken of brevity, I really must run off now, my dear. But I will leave you with one last verse, a few stanzas from a Byron poem I think beautifully captures the Intersection of Love and Violence. Enjoy.

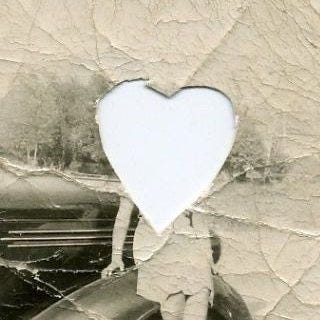

3 [...] Though pleasure fires the madd'ning soul, The heart-- the heart is lonely still 6 My Thyrza's pledge in better days, When love and life alike were new! How different now thou meet'st my gaze! How ting'd by time with sorrow's hue! The heart that gave itself with thee Is silent-- ah, were mine as still! Though cold as e'en the dead can be, It feels, it sickens with the chill. 7 Thou bitter pledge! thou mournful token! Though painful, welcome to my breast! Still, still, preserve that love unbroken, Or break the heart to which thou'rt prest! Time tempers love, but not removes, More hallow'd when hope is fled: Oh! What are a thousand living loves To that which cannot quit the dead?

From “to Thyrza” by Lord Byron (1811). Taken from “Lord Byron: the Major Works, Oxford World’s Classics” (reissued 2008)

Until my next letter,

x Sabrina Angelina, the White Lily Society

Currently reading: “The Monstrous Feminine: Film, Feminism, Psychoanalysis” by Barbara Creed // Most recent read: “Lady Caroline Lamb: a Free Spirit” by Antonia Fraser

White Lily Society links // Sabrina Angelina links

𖦹𖦹𖦹 Ooh, you wanna subscribe so bad 𖦹 You want to become a martyr of deliciousness so bad 𖦹 You want to click the little red button below this and insert your email address sooooo bad 𖦹 Come, join us 𖦹 You know you want to 𖦹𖦹𖦹

Actual term coined by Annabella Milbanke (Lady Byron) in regards to the extreme levels of fame and popularity Byron faced after publishing [the first few cantos of] “Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage” in 1812.

Scribbled quote from Andrew Stauffer’s talk at the “Byronic all-dayer” event. From a lecture called “What Byron teaches us about democracy”, British Library, 2024.

Capitals added by yours truly.

As Byron himself referred to it in a note, ca. 1813. Reference to Shakespeare’s “Hamlet” (1623)

From a letter Byron sent to his friend Hobhouse, ca. 1811

John Polidori’s “the Vampyre” (1819), at first mistakenly thought to be written by Lord Byron popularised the idea of the “high class” aristocrat vampire, moving through high society seducing and charming