“The horror was for love”, goes the opening line to a classic villain monologue in Guillermo Del Toro’s 2015 film Crimson Peak. We all know the drill; we are well into the third act of the movie and our villain, Lucille, has indeed just committed several horrific acts, including murder and incest. Everyone watching is most definitely holding their breath, waiting to see what she has to say for herself. And then she starts with those five words, barely a line even. How grotesque that she posits love as her main motive, how utterly absurd. Yet it is not a single one of those, or other synonymous words, that I would ascribe to Lucille’s motives. No, I posit that they are not grotesque, not horrible, not terrifying; instead they are deeply, and truly Romantic. To the bone.

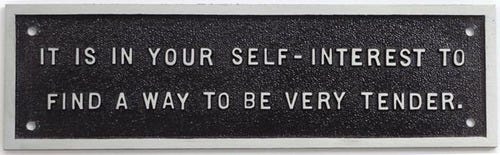

Romanticism is having its second coming in popular culture as we speak. Nevermore has the word romanticisation featured so heavily in social debate, nor have the words love and horror been considered such a perfect pairing. When venturing into [mainly feminine] social spaces the conversation has flavoured itself with the philosophy of New, revived Romanticism, the Erotic, and ideas of love and terror, and melancholy. Like a rose coloured wildfire, images with phrases like “a morbid longing for the picturesque” have slid into the cultural lexicon of what it means to love, and into their respective villain monologues on the big screen.

And like love faces the most tender scrutiny, likewise have I wished to examine this New Romanticism, this revived Romanticism, in all its terror-struck and morbid ways. And so I have consumed nothing but Romanticism for the last few weeks, and if you’ll allow me to do so, I’ll tell you what I’ve learnt.

I. Love & violence and its Erotic roots

“[…] as if Evil were the most powerful means of exposing passion”

Georges Bataille, “Eroticism” (1957)

Romanticism, both the initial kind and the New, revived kind, are rhizomatic in the sense that its roots lie in traditional ideas of eroticism, which in turn offshoots into love, violence, horror, melancholy, and terror. But let’s not place the lover before the love. Let’s begin at the root of all this evil, and all this romance. Let’s begin with the Erotic.

In its most basic, banal interpretation, the Erotic is that which lives on the fringes of what is socially acceptable: the taboo. What is considered erotic is exciting and enticing, although not always the other way around. If we are ourselves, we are mankind, then the Erotic is the call of the void. It exists in whatever lies just out of view and whatever extends just out of reach. The Erotic is the empty, dark and forlorn hallway you cast a glance in but never dare to enter, until you eventually do. You couldn’t help yourself, it just called out to you.

Make no mistake. That there is a link between the Erotic and death or violence is not a novel proposition in any way. But to see these notions transfer from hidden subcultural gems to the more latent layer of popular cultural is entrancing to say the least. Georges Bataille’s book on eroticism is often regarded as depositing the popular theory on eroticism in philosophical academia, and in his writing he discusses eroticism as a fraction of disruption where you seize to be, even if just for a moment. It is that interlude, that pause of existence, that gets you closer to a continuous existence; to death and everything in the infinite beyond. Human beings are discontinuous in the sense that we, as individuals, die, we perish. Yet existence itself is continuous and keeps fuelling itself through the motions of life and death. Thus Eroticism is mankind’s attempt to bring continuity into an eternally discontinuous world. It is a metaphysical pursuit through and through. What is Erotic is that what reminds us of that continuous existence outside of ourselves; taboos, death, violence, religious sacrifice, mysticism, and of course Beauty.

To many, Eroticism is often synonymous with sex. Bataille’s work explains this through its reasoning that sex is the ultimate form of violation, and “the whole business of eroticism is to destroy the self-contained character of the participators as they are in their normal lives”. Nakedness as a motif, as a symbol, factors into this as well; it literally strips the self away. It consumes the ideas we have of ourselves whole, therefore leaving space for the Erotic; that which transcends our individuality.

II. I want us both to eat well

“[…] there’s such a romantic factor and aspect of desperation. It’s so bad, but love that is healthy is so good, and so unappealing, to me, at least. […] I have to want to eat you. If I don’t want to eat you, then it’s not real love”

Ethel Cain, in interview with Vice magazine (2022)

The recent resurgence of cannibal romance media (“Bones and all”, “Hannibal”, Ethel Cain’s album “Preacher’s daughter”) parallels the renewed interest in Romanticism. The genre is Romantic because of its core convictions that love is tragic, that love is fatalistic; that love consumes. There is a fundamental romanticism and Eroticism latent in the very idea of cannibalism; the idea of loving something so much that you need it to be a part of you. And this undoubtedly matches the Revived Romanticist movement’s fervour for love.

In the New Romantic movement the subjects enamoured by it frequently revert to biting. Girls have taken to wearing Victorian lockets with images of their loved ones, both real and fictional, and just like the eighteenth century women they mimic they make lover’s keepsakes out of blood, teeth and hair. They write poetry, they become enraptured with their lovers. There is an intense preoccupation with lobotomies, with a lovesickness so intense it becomes physical, or a melancholy that twists its way around darkened candlelit bedrooms. Romantic suffering becomes religious, obsessive even. It transcends the bounds of personality and personhood completely. It slithers and surrounds its blissful victims.

In many ways the movement tries to revive the all-consuming ways of Romanticism, but with a focus on the women as the would-be Romantic aggressors, as the “evil”. They are Female Byronic heroes; brooding and capable of moral corruption, yet also capable of infinite love. They are conduits of transcending passion. Instead of loving in the passive tense, instead of being loved, the Romantic Revival posits the women at the centre of its movement as loving in the active tense, and to their fullest capacity.

Before the 2020’s cannibalism era, the era of the 2010’s was plagued with abundant vampire franchises. From “The Vampire Diaries” to “Twilight” to “Interview with the vampire”, “the Originals” or “Vampire Academy”, the Gothic love story reigned supreme. And characteristically, with the Gothic creatures came Gothic Romanticism. Althroughout, there is the threat of consumption, lingering like a soft but constant ringing in your ears. A reminder of impending vampiric doom, and underneath it a shimmering fear of romance eating us whole, of love and longing being so intense it proves fatal in more than an emotional aspect. And that is precisely the appeal. Loving that which is broken or bad, or Love as a leviathan orb, as something larger than ourselves, is enticing and Erotic. It was this way for the earliest Romantics, and it is that way for the New Romantics.

A poem I adore writes “I’m doing a balancing act with a stack of fresh fruit in my basket. / I love you. I want us both to eat well”. These lines resonate with me because they reflect the thoughts I could never have put into words myself. Yes, I want us both to eat well. And by eat well I mean eat love; be nourished by life and romance and Beauty, and everything else that feels so out of reach but never is. Infinite solace of the material earth. I want to eat well for your eventual nourishment, you who is a stranger to me now but might not be in a month. You for whom I will commit the most atrocious, violent acts with nothing but your name on the tip of my tongue. Teach me how to be better, how to be worse, how to be.

III. Of being helpless: romanticism and tragedy, and the pursuit of Beauty.

“In the midst of winter I found within myself an invincible summer”

Albert Camus

“Beauty is terror. Whatever we call beautiful, we quiver before it” & “Beauty is rarely soft or consolatory. Quite the contrary. Genuine beauty is always quite alarming”

Donna Tartt, “the Secret History” (1992)

Tell me if you have heard this line spoken before; nothing that is good comes easy. Unfortunately, I have no way of knowing what you answered to that, so instead I wish to tell you that I have, but I don’t believe in its objective truth. I think many things could and therefore should be easy, but they simply aren’t so. In particular, feelings aren’t icebergs or foamy ocean tips or metaphors easily understood and written; they are complex sequences of events. They may deceive you into thinking them unembellished and un-ornamented. Especially love, deceptive as it can be.

Yet love is never a peaceful affair. Even when it is smooth sailing, there is always the anxiety of the next wave capsizing the ship. Or as Bataille writes; “Passion fulfilled provokes such violent agitation that the happiness involved, before being a happiness to be enjoyed, is so great as to be more like its opposite; suffering.” Or “The likelihood of suffering is all the greater since suffering alone reveals the total significance of the beloved object” or “Love spells suffering for us in so far as it is a quest for the impossible, and at a lower level, a quest for union at the mercy of circumstance”.

Adoration is not a daytime creature, it lives at night in between the dark’s decay and a motorised mind working overtime. If it was easy to fall it would not involve so many violent words; heartbroken, lovesick, infatuated, gutted, yearning, longing, languishing.

A lot of what the New Romantics are selling is familiar wares; the picture of obsessive, fatalistic, grand love. But coupled with it is a prevailing undercurrent of love for the mundane that flows throughout the movement’s main motifs; there is a deep romanticisation of life, a philosophical search for Beauty in the mundane, and abundant attention for the small, domestic and even unremarkable details of love. Love and Romanticism here are tools to feel things fully and wildly. They allow devotees an almost radical intoxication with life. The horror was for love, and the love was vital to live. The quest here is simply to love and be in love, to think of giving love as a goal in itself, to pursue Beauty wherever possible.

IV. The girl bites back or a woman’s violence

“To be the object of desire is to be defined in the passive case. To exist in the passive case is to die in the passive case- that is, to be killed.”

Angela Carter, “the Sadeian Woman and the Ideology of Pornography” (1997)

One abstractly noticeable facet of this New Romantic movement is the fact that it is undoubtedly feminine. It is unequivocally tied up by the strings of the female gaze (a term which has recently been dulled through use, unfortunately) and the feminine experience as a whole. If “Girlhood is like godhood: a begging to be believed”, then a woman’s experience of love is an inherent belief, or maybe a will to believe, in an evil that can be loved despite its malice and moral wrongdoings. The beauty in this Romantic ideal is that it is both realistic and mystical; it requires a suspension of disbelief while also asking, inherently, for a belief. It is the kind of moral contradiction that can only be conjured up in a woman’s desires.

Violence and love have been inextricably linked in the feminine experience since the first apple tree grew in the garden of Eden, that one symbol of punishment and liberation that would haunt all of womankind like the gender’s very own mark of Cain. There is in this the feminine ideal of an emotional, fragile being; the biblical woman who is expected to be nothing but kind and motherly, and gets trampled in return. There is the inherent violence of womanhood that exists in its cycles of blood and pain, that inevitably leads to more blood and more pain. Love is good, but sex is often not fruitful or even painful for women. Carrying a child is both depicted as a divine act of creation- images of clouds and smells of soft cotton- as well as the worst kind of body horror any sick soul could conjure up.

There is a scene in Game of Thrones in which character Jon Snow is discussing high ladies with his girlfriend, Ygritte, who grew up in the wild and thus away from high society, where he remarks that those ladies would faint at the sight of blood. To which Ygritte responds; “Why would a girl collapse at the sight of blood? […] girls see more blood than boys”. To posit that women are strangers to violence is to lie. And what a dim-witted, simple-minded lie it is. Women continuously bathe in violence, in fear, in love. And there has not been, and shall not be, a day when that is not true.

In a way there is a defeat and a liberation in this revived movement, and I can’t for the life of me seem to figure out which one is dominant. In many ways these “evil” women are a response to a world that does not allow women to be evil, but instead of “true” evil there is a kind of immorality that exists on the fringes of the black and white, good vs. evil dichotomy. Make no mistake; the evil these women think to see in themselves is most often not deserving of the label evil. When we read evil, we have to think flawed.

Is it a win for women to give in and be evil in recognition of a world that has always been cruel to them? Is this an acceptance of the violence of love, or is it a perpetuation of it? Is Romanticism merely a coping mechanism to deal with a meaningless, discontinuous existence? Does it matter whether this movement is moral or ethical, when it is essentially the antithesis of morality?

I’ve let myself get enveloped in this New Romanticism; I’ve read their texts and steeped in their media of choice. I’ve listened to Nicole Dollanganger, and Lana del Rey, and Ethel Cain’s music. I watched the Virgin Suicides and I read Keats. And I understand, I see the appeal. On what is, hopefully, the tail-end of an increasingly depressing state of global affairs, I can’t fault people for reaching beyond themselves into Romanticism, into absurdism, into nihilism even. That is the lure in of all of this philosophical rhetoric; to just exist and accept and let morally flawed inner workings be. To instead aspire to something higher, beyond the self, beyond the physical realm; to reach for love and Beauty wherever possible.

Lucille’s monologue continued beyond that first phrase to posit that “The things we do for love like this are ugly, mad, full of sweat and regret. This love burns you and maims you and twists you inside out. It is a monstrous love and it makes monsters of us all.” So if we are indeed doomed, if we are monsters of love, then let our love be immortal and outlive us all. Love is a flesh wound, love is a bloodstain, love is a violation. Love is total obliteration; it is earth-shattering devotion, a loss of control and a loss of self. It is the calmest, most natural and simplest thing in the world to those who are enveloped in it.

How does one overcome sadness? Or terror? Or grief? You choose to see the beauty in it. You let it shatter you and then you rummage through the ravages, hands steadily gaining cuts, and you pick out your favourite shards to hold up to the sun, so you may see them shimmer once more. And then you let the resulting cuts serve no purpose but to enhance the Beauty of it all, knowing they will heal. And maybe, just as long as the sparkle shows, you have ascended beyond yourself into the continuous.

x Angel

White Lily Society links // Sabrina Angelina links

If you liked this essay, please consider pledging your soul to the White Lily Society. It’s completely free! Come, become a martyr of deliciousness.